Daedalus and Icarus : A Parable of Human Flight

Jacob Peter Gowy's The Flight of Icarus, painted in 1635–1637. The painting depicts Daedalus and Icarus, the latter falling after he flies too close to the sun, melting the wax in his wings. Image source.

The oldest and most storied myth of human flight is the Greek myth of Daedalus and Icarus. Any history of flight, if tracked back far enough, will find it’s inception rooted in this timeless tale of youthful hubris. Over the centuries, the name Icarus has become synonymous with over-ambition, and has inspired countless other stories relating to human flight.

As the story goes, Daedalus was an Athenian master craftsman who was tasked by King Minos to design a labyrinth, or maze, on the island of Crete in order to hold a Minotaur. After he completed the labyrinth, there’s a couple different versions of the story. The first is, the king imprisoned Daedalus and his son Icarus in a high tower to prevent Daedalus from sharing knowledge of the labyrinth with anyone else. The second is, the king imprisoned Daedalus and Icarus inside the labyrinth after Daedalus attempted to help Minos’s enemy Theseus navigate the labyrinth in order to kill the Minotaur. Either way, Daedalus found himself and his son imprisoned by the king.

In order to escape, Daedalus devised a plan to fly off the island and make their way to Sicily. He built two pairs of wings from wax and feathers, organizing the feathers by size across each wing in order to mimic the wings of a bird. After testing out the wings, Daedalus taught Icarus how to fly, and instructed him not to fly too high or too low. If he flew too high, the sun would melt the wax of his wings. If he flew too low, the moisture from the sea would weigh him down.

After lifting off and escaping from their prison, the two began flying over the sea toward Sicily. After some time, the joy of flight proved too much for young Icarus, who flew upwards toward the sky, ignoring his father’s instructions. Just as his father had warned him, the wax of his wings melted from the heat of the sun and he fell to the sea and drowned. The distraught Daedalus completed his flight and successfully escaped, however. There are various tales about the rest of Daedalus’s life, but the fate of Icarus has stuck much deeper in the minds of those who know the tale, and today he is much more well-known than his father.

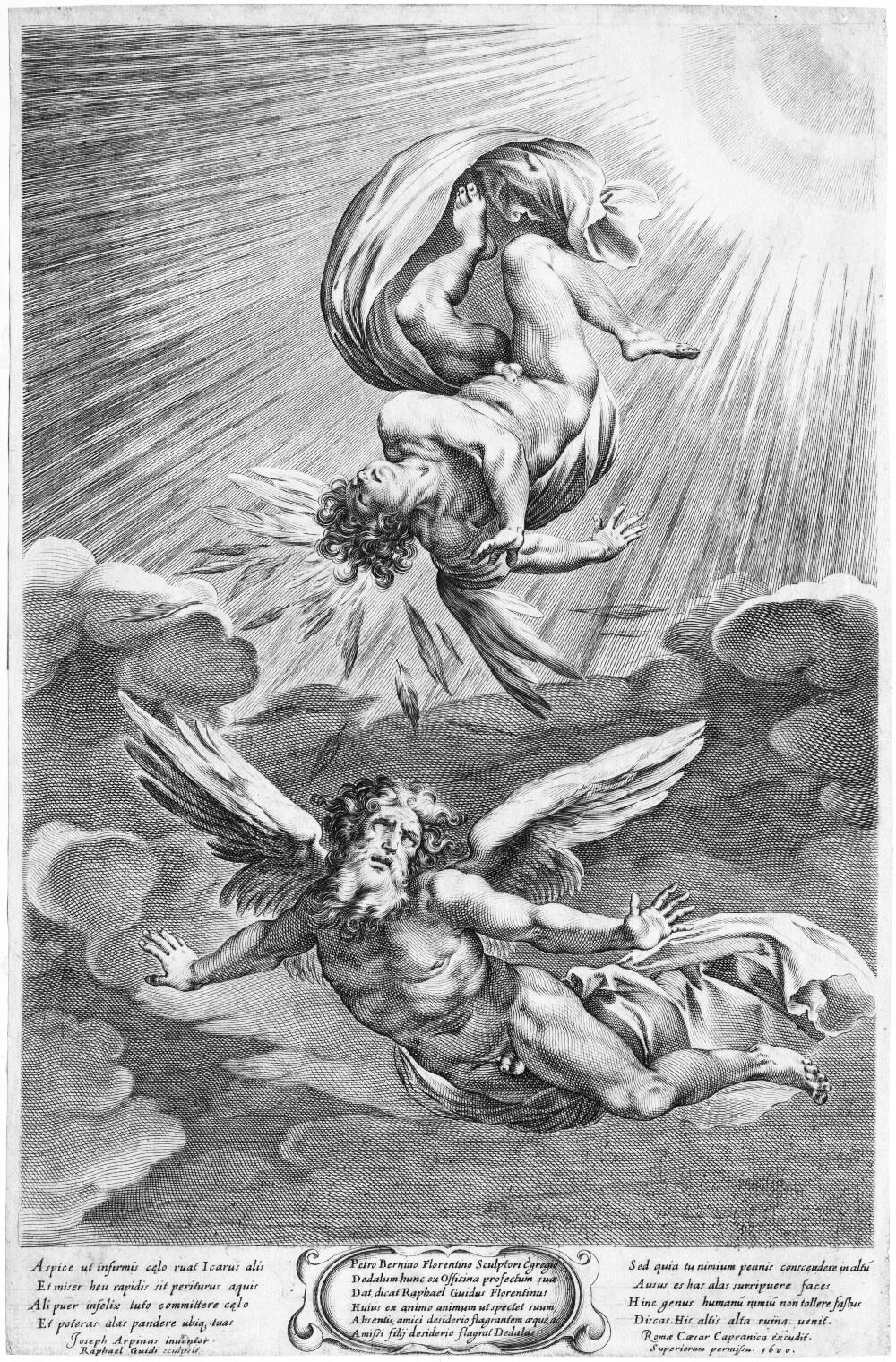

A 1600 engraving by Raffaello Guidi showing Daedalus and Icarus in flight, with Icarus’ wings having just melted from the heat of the sun.

The myth of Daedalus and Icarus is woven closely with the history of the human need for verticality, and there’s three distinct themes worth pondering. The first is the innate need we all have to escape the surface of the earth. The young Icarus, through the ingenuity of his father Daedalus, was given the gift of flight, and on his first attempt he flew too high and payed for it with his life. The innate need within Icarus to escape his surface-based prison proved too much for him, and he got lost in the joy of flight.

The second is the duality of height. Humans crave height and verticality, but with greater height comes greater danger. As one rises higher into the air, the dangers from a lack of oxygen, low temperatures, and the potential for a fall all become greater. Icarus was unaware of the first two, of course, but the third became a reality for him after he failed to heed his father’s warnings.

The third is the public interest in the story, and how Icarus is much more well-known than his father. Think about it: according to the myth, Daedalus built the world’s first flying machine, he was the first human to achieve flight, and he successfully flew across the Mediterranean. Even so, he’s failed to enter the popular consciousness in the same way his son has. The character of Icarus has become synonymous with over-ambition and youthful hubris, and his story functions as a cautionary tale for humanity even today. Popular culture, including literature, music and film, has myriad references to Icarus, and he’s even had his own video game.[1] Icarus is the source of the phrase he flew too close to the sun when describing over-ambition. He’s also been the subject of many works of visual art throughout history, as evidenced by the works pictured throughout this piece.

The Lament for Icarus, painted by Herbert James Draper in 1898. Icarus can be seen with his massive wings after drowning in the sea. Height represents both safety and danger, and the danger got the best of Icarus, who flew too close to the sun. Image source.

The myth of Daedalus and Icarus is a tragic tale, but it encapsulates the human need for verticality and it’s the proper starting point for any history of human flight. There are many myths and legends that deal with flight and the human need to escape the surface of the earth, but the myth of Icarus and his fall is no doubt the most popular. It has endured over the centuries, and the name Icarus has become a symbol for the simultaneous joy and dangers that are associated with escaping our surface-based prison.

Read more about other ideas for flying machines here.

Check out other myths and legends that deal with flight here.

Read more about verticality throughout the arts and literature.

[1]: In 1986/87, Nintendo released the video game Kid Icarus for its Nintendo Entertainment System.