Earth, Air, Water and Fire : The Verticality of The Classical Elements

Illustration from 1659 by Basil Valentine, for his work Azoth of the Philosophers. The image shows an azoth, which is an alchemic emblem depicting the composition of the universe. At the core of the diagram are the four classical elements: earth (lower left), air (upper right), fire (upper left) and water (lower right).

Ever since humanity became self-aware, we’ve been trying to understand the world around us. We perceive our surroundings through our five senses, which are the only window we have into the world outside our bodies. Throughout history, our ancestors have created myriad different theories and ideas that attempted to explain this world and how it’s composed. One theory was common to nearly all early civilizations, and it identified four basic elements: earth, air, water and fire. Collectively, these four elements are called the classical elements.

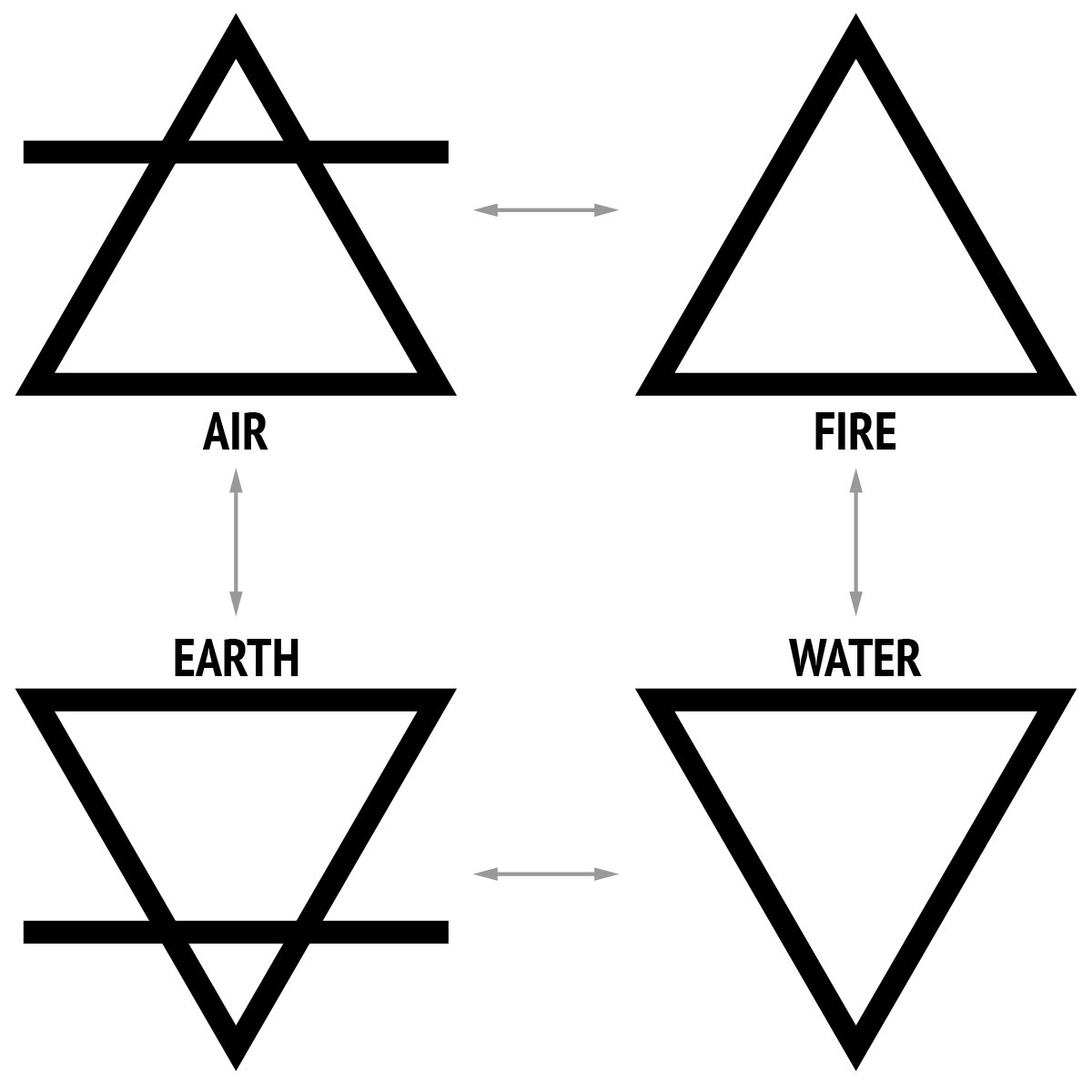

What made all these early cultures independently identify earth, air, water and fire as the building blocks of our world? We can find variations on the classical elements in Ancient Greece, Babylonia, Persia, Japan, China and India, among others.[1] For the most part, these were independent cultures that mixed very little, yet each came to the same conclusion when theorizing on the makeup of our world. One thing they did have in common was verticality. Verticality is common to every human being who has ever lived, and if we examine the four elements and pick apart the relationships between them, we’ll find verticality at the center of it all.

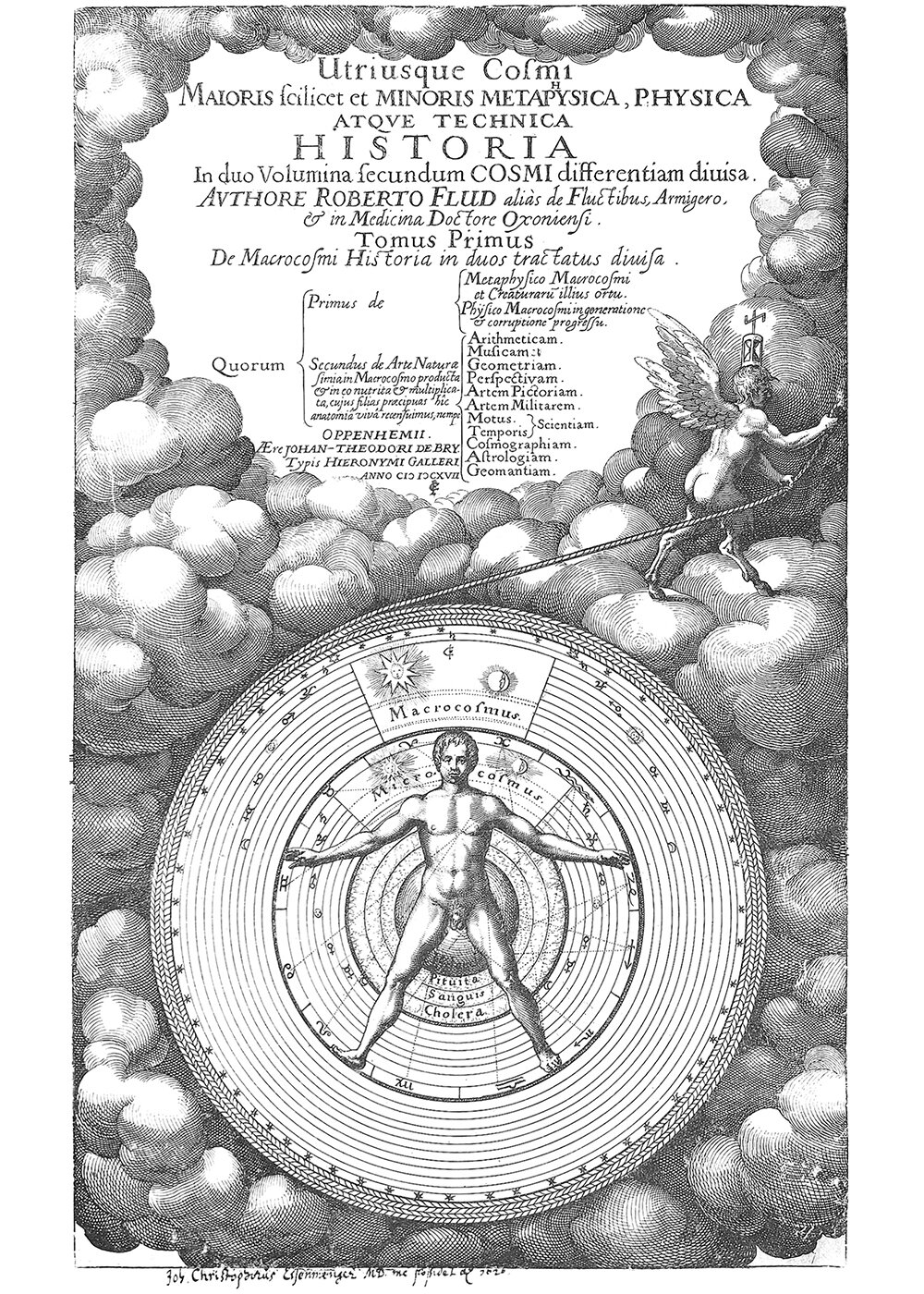

Frontispiece to Robert Fludd’s 1617 work Utriusque Cosmi. It shows Fludd’s idea of man (the microcosm) and the universe (the macrocosm). It illustrates an early theory of the human relationship to our surroundings.

Today, we understand the world to be made up of atoms, and each type of atom represents an element. These elements combine together to form molecules, which are the building blocks of the physical world we inhabit. This is a grossly simplified explanation, of course, but it represents what the classical elements were trying to do. They were trying to understand how our physical environment is composed, and they were theorizing it without modern technology.

To begin with, consider the human body and the environment we exist in. We stand upright on two legs, in a vertical stance. We’re constantly pulled down along the axis mundi, and we’re always standing on top of a solid surface of some kind. This solid surface is earth, which is the first element. It encompasses all solid matter, which is always pulled down towards the ground, like our bodies. Earth represents the surface world, which we humans exist on. The next element is air, which always exists above earth. Air is not beholden to gravity in the same way earth is; it is essentially the anti-earth, and it occupies the space above the surface, as well as the space above our heads. Air represents the sky, which is the place we humans seek to reach through verticality.

Together, earth and air represent our physical environment. At it’s most basic, our existence depends on a surface to stand on and a place to move around in. The two are diametrically opposed along the axis mundi, and their relationship is based on verticality.

Next, consider all the stuff that goes on in our physical environment. These are the elements of life. They are based on movement and dynamism, and they’re also diametrically opposed along the axis-mundi. The first is water. Water is the essence of life, and it pairs with earth, since it’s always flowing downward toward the surface. Over time, this downward movement carves up the earth into mountains, valleys, canyons, and other topographic features. Together, earth and water are always below us, or headed that way. Paired with water is the fourth element: fire. Fire is the element of death and destruction. It consumes life, and it also pairs with air. Flames flow upward and occupy the same space as air, and just like flames, the smoke created by fire rises up and away from earth and water.

Water and fire, much like earth and air, are also diametrically opposed along the axis-mundi. Water represents downward movement, while fire represents upward movement. Water is the essence of life, while fire consumes and destroys life. The two also cancel each other out, as too much water will extinguish fire, and too many flames will dry up water.

Diagram of the macrocosm from 1617 by Robert Fludd. It shows the four classical elements, arranged along the axis-mundi as concentric spheres. From inside to outside, the four elements are terra (earth), aqua (water), aer (air), and ignis (fire).

The classical elements are no longer recognized as the building blocks of our world, of course, but they do loosely correlate to the modern idea of the states of matter: solid (earth), liquid (water), gas (air) and plasma (fire). These states of matter are based on the relationship between molecules and thermal energy, which could be what the classical elements were honing in on, before the mechanics of such things were properly understood.

The commonalities among all the early theories for the classical elements suggests there is something primal going on here. Our surface-based existence is governed by the universality of gravity, which acts vertically along the axis-mundi, so I suppose this is to be expected, but it cannot be ignored that the relationships between the four elements are so deeply rooted in verticality.

Read more about the axis-mundi and how it relates to the human need for verticality here.

[1]: A few cultures identified a fifth element as well, but the main four are by far the most common. Plato identified aether as the fifth element in Ancient Greece. Ancient Hinduism identified akasha, or void, as the fifth element. Ancient Tibetan philosophy and the Japanese also identified void as the fifth element. The Ancient Chinese identified metal and wood as the fifth and sixth element.