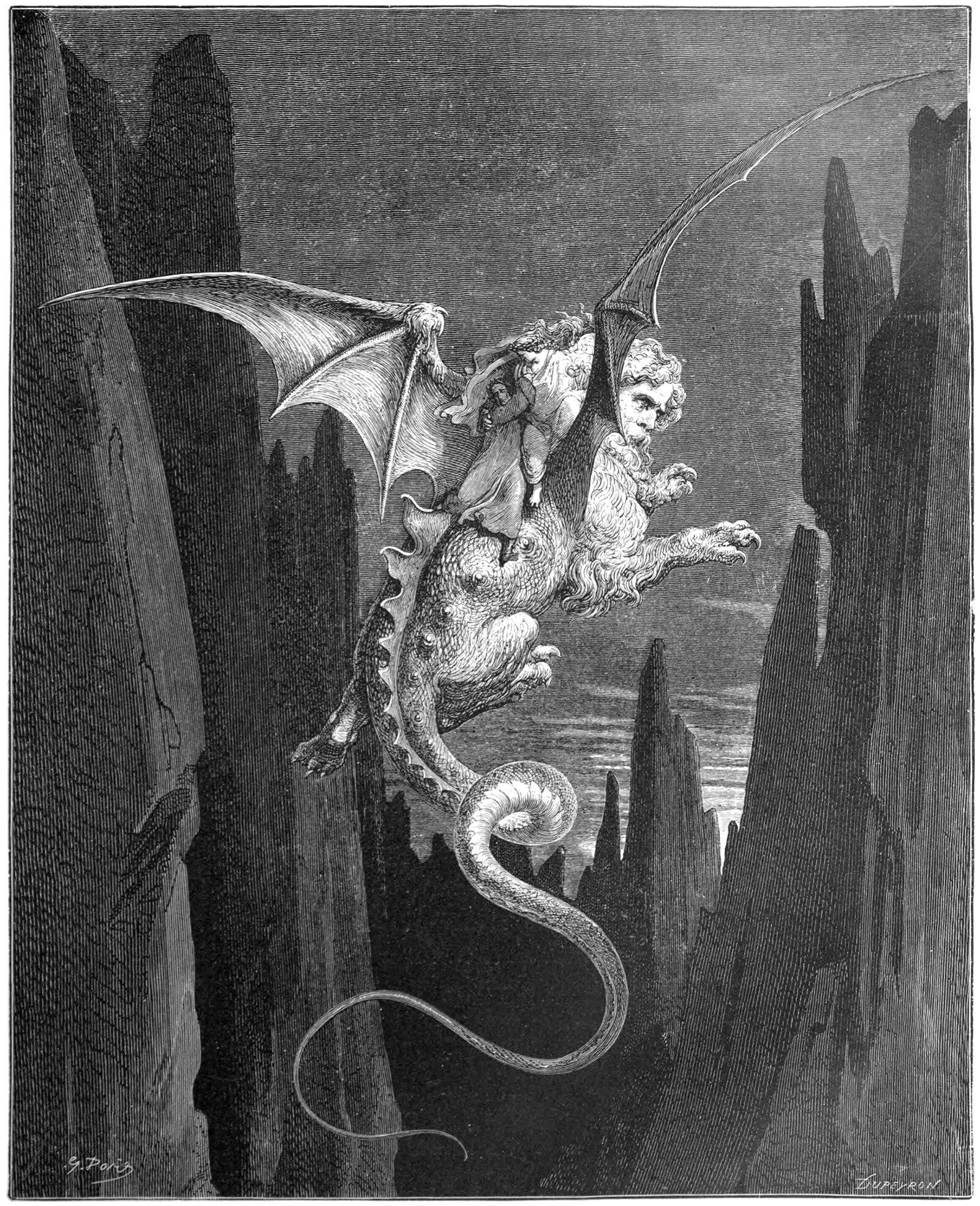

The Flight of Geryon

Illustration by Gustave Doré from 1867, showing a scene from Dante’s Inferno where Dante and Virgil ride on the back of the monster Geryon.

The above illustration by Gustave Doré shows a scene from Dante’s Divine Comedy. The epic poem follows Dante and Virgil as they pass through Inferno, Purgatorio and Paradiso, and it deals with the concepts of Heaven and Hell, as well as the Seven Deadly Sins. This scene is from Canto XXVII of Inferno, when Dante and Virgil mount the back of the great beast Geryon and fly down from the seventh to the eighth circle of hell. When Geryon leaps from the seventh circle, Dante is paralyzed with fear and loses focus on everything except for the great beast. He also compares the experience with Icarus and Phaedus, two figures in Greek mythology who had similar experiences with flight. The full passage follows:

There where his breast had been he turned his tail,

And that extended like an eel he moved,

And with his paws drew to himself the air.

A greater fear I do not think there was

What time abandoned Phaeton the reins,

Whereby the heavens, as still appears, were scorched;

Nor when the wretched Icarus his flanks

Felt stripped of feathers by the melting wax,

His father crying, “An ill way thou takest!”

Than was my own, when I perceived myself

On all sides in the air, and saw extinguished

The sight of everything but of the monster.

-Inferno, Canto XXVII, lines 106-114.

By referencing Icarus and Phaeton, Dante is tapping into the human need for flight, and the fear he experiences is a common one among humans. The danger of falling is an ever-present possibility when flying, and Dante, having never experienced flight before, is so fear-stricken that he can focus on nothing but the beast carrying him. Doré illustrates the scene by showing Dante struggling to hang on to Geryon’s back, grasping Virgil in the process.

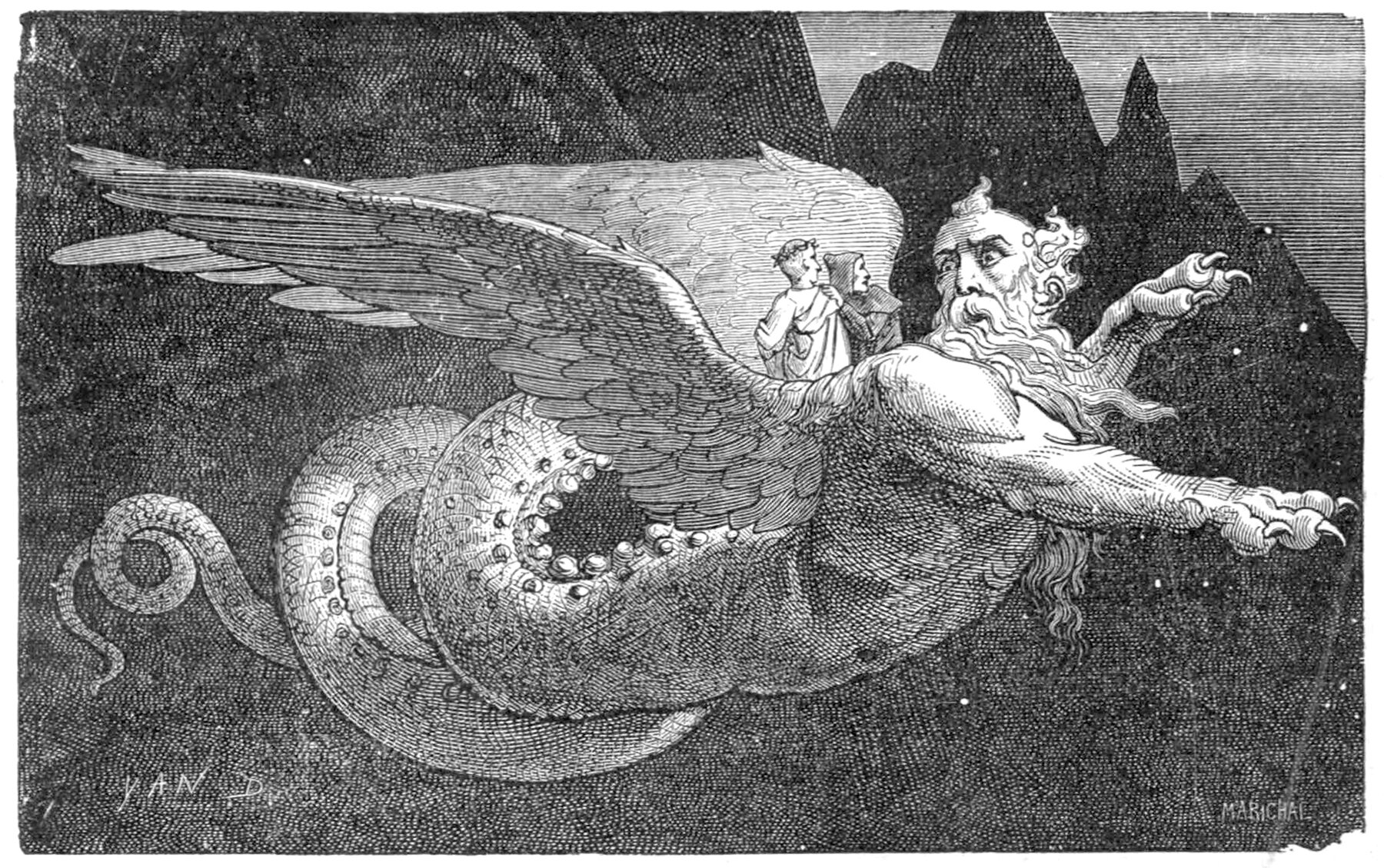

Illustration of the flight of Geryon by Yan Dargent in 1870. Dargent took a different tone than Doré, showing Dante and Virgil safely standing on Geryon’s back.

Here’s another illustration of the scene, drawn in 1870 by Yan Dargent. Here, Dargent shows Dante and Virgil safely standing on Geryon’s back in mid-flight. The terror felt by Dante isn’t present here, and the two men seem to be calmly discussing something with the beast. It’s not as effective as Doré’s version and it doesn’t convey the emotions Dante is describing, but it’s an interesting counterpoint to look at.

Sketch of Dante and Virgil’s flight on Geryon, drawn in 1821 by Joseph Anton Koch. Koch shows the pair flying above a group of sinners below.

A third example, drawn in 1821 by Joseph Anton Koch, shows Geryon as a lizard-like creature, smaller than the previous interpretations. Dante and Virgil are calmly riding his back, and the terror described in the text isn’t shown here either. This is interesting, because Dante makes a point of describing his fear in detail, but Gustave Doré seems to be the only artist who chose to show this.

Geryon’s flight is a popular subject for artists, and a quick internet search will show myriad examples of artists recreating this scene. Interestingly, Gustave Doré’s version is the only example I could find that shows Dante’s fear. This not only shows just how great of an artist he is, but it also shows the innate human need for flight. All the other artists chose to focus on a fascination with flight rather than a fear of it. By showing Dante and Virgil calmly surveying their surroundings while riding on Geryon’s back, the act of flight becomes a positive experience rather than the negative experience that Dante and Doré depict. This forced-positivity is evidence that all humans have an inner drive to achieve verticality, and this drive is more powerful than any fear that may accompany it.

Check out other posts on Dante’s Divine Comedy here.