The Singer Building and the Power of Nostalgia

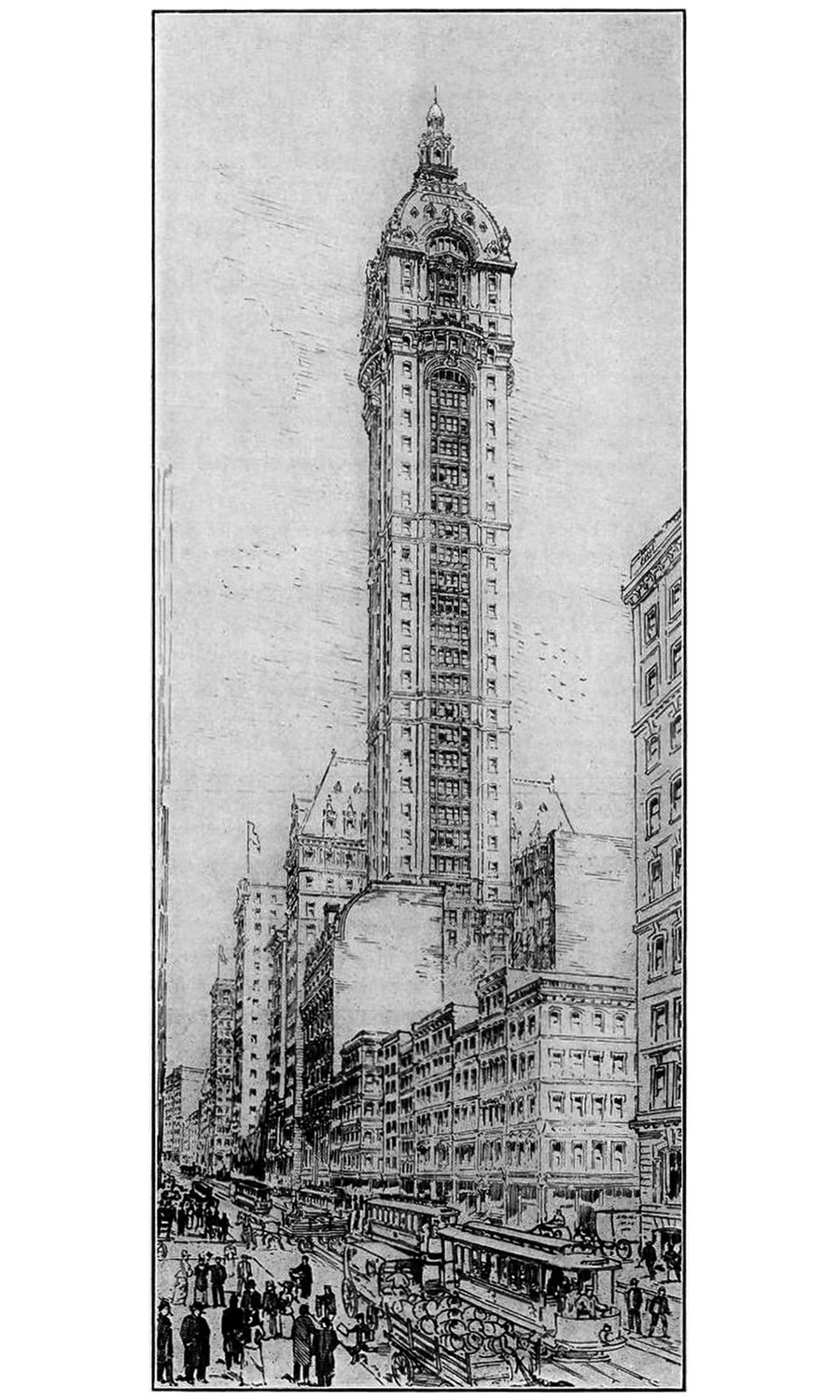

Illustration showing the Singer Building, which was built in Lower Manhattan in 1908 and demolished in 1967. It remains in the public consciousness and is a symbol of lost architectural icons.

There’s a vague sense of permanence every time a building gets built. After the final brick gets laid and the first occupant enters, it somehow feels like it’ll exist forever. This is particularly true for tall buildings, because they take so much more time and effort to build. The spaces they house, especially those built high above the surface, feel like newly conquered land, fought for and won by the efforts of the men who design and construct them. These men have done battle with gravity and emerged victorious, and every skyscraper in existence is a record of a similar battle fought at its site.

This sense of permanence can be tested, but it rarely breaks with tall buildings. Because of their size, they are quite expensive to demolish, so they usually find new life in other ways. Some become outdated or their style falls out of fashion. These can undergo façade restoration, like New York’s Lever House. Some have neglectful owners who let them fall into decay. These can be bought up by a new owner and renovated, like New York’s Equitable Building. Some are priced out or crowded out of the cityscape by newer, taller structures around them. These can be restored to their former greatness and marketed on their old-world charm, like Chicago’s Reliance Building. Each of these examples found new life and continue to serve occupants to this day. On the rare occasion when a tall building does get demolished, it’s usually due to a combination of most or all these factors. One such example is the Singer Building of New York. It was the tallest building in the world when it was completed in 1908, and in 1967 it was the tallest building in the world to be demolished by its owner. It’s a tragic tale that could’ve and should’ve been avoided, and I’ll dig into why it happened here.

The Singer Building was built in phases between 1897 and 1908. The tower portion was the last to be built, and its elaborate crown design immediately distinguished it from other skyscrapers. It was built as the headquarters of Singer Sewing Machines, which was booming at the time. The tower’s architect, Ernest Flagg, was an outspoken critic of skyscrapers and he took the commission to raise awareness for his criticisms. He believed urban buildings should be capped at 10 stories in order to preserve access to light and air at street level. Because of this, he designed Singer as a slender tower with small floor plans, set back from the street line.[1] This slender profile also allowed the interior to be lit mostly by daylight, reducing the need for artificial lighting required by larger, deeper towers. Unfortunately, this would become a major factor in the building’s eventual demise.

Photo of Singer Building, circa 1915. Pictured in the background is the Woolworth Building, which was also the world’s tallest building when it was built.

Singer occupied their tower until 1961, when they moved to Rockefeller Plaza in Midtown. Their building was subsequently bought and sold a few times, until U.S. Steel purchased it in 1964. By this time, just a couple blocks away the construction of the World Trade Center was underway. This was causing real-estate values in the neighborhood to skyrocket, and U.S. Steel wanted in on the party.

The World Trade Center towers provide a perfect comparison with the Singer Building, and the differences explain why the latter was no longer favored by commercial tenants. Much had changed in the decades since Singer was built, and commercial office towers had gone through a transformation. Artificial lighting and air conditioning were now commonplace, which led to much larger floor plates and much bulkier towers. Singer’s slender tower and compact floor plates were now outdated and largely unusable for tenants. In addition, elevator technology had greatly improved, which allowed for much taller buildings to be built. This allowed land owners to construct more rentable space, which led to higher profit margins. Furthermore, the mid-century saw the emergence of the International Style, which rejected traditional architectural motifs in favor of simple steel façades, without all the ornament of historic styles. The ornate design of the Singer Building was now seen as a relic of a bygone era, without much of a market to slot into. Combine this with the soaring real-estate values, and it quickly became a target for destruction.

Now, this isn’t to say the building wasn’t loved. It was still seen as an icon of New York and early skyscraper design in general, but these beliefs don’t pay the rent. Previous owners had tried to convince new tenants, like the New York Stock Exchange, to move in, but they were unsuccessful. The New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) was formed in 1965 to preserve buildings like Singer, but they couldn’t landmark it. Since U.S. Steel had previously met with the city and begun plans to raze the building, the new laws dictated that the LPC would need to find a new buyer, or the city would need to buy the building.[2] Neither of these options were possible, so the fate of Singer was sealed.

The Singer Building was demolished from 1967 to 1969. In its place, the U.S. Steel Building rose. It followed the model of the World Trade Center towers. Large, bulky floor plates, artificial lighting, air conditioning, and a simple steel façade, all placed at the center of the site with a plaza surrounding it. What was once ornamental and interesting was now dull and bland.

Original tower floorplan of the Singer Building. The plan was designed to accommodate a ring of private offices and little else.

Most skyscrapers stand the test of time because they’re simply too big to demolish. It’s a long, expensive undertaking to demolish them, and there aren’t too many scenarios that make the latter feasible. Usually it’s much less expensive to renovate, but in the case of Singer the real-estate values of Lower Manhattan made the demolition option possible. It’s a tragic story full of what-ifs. What if the New York Stock Exchange had decided to relocate there? What if the LPC was able to get it landmarked before U.S. Steel came along? What if an owner came along who wanted to renovate the tower into something new? For the last two questions, the answer lies just a few blocks away in 20 Exchange Place.

The story of 20 Exchange Place almost exactly mirrors the Singer Building, with a much better ending. Both buildings were built as headquarters for their clients (20 Exchange was built for the City Bank-Farmers Trust Company). Both buildings had large, bulky bases topped with slender towers which were set back from the street. Both buildings had lavishly-decorated ground levels and towered over their surroundings, offering unparalleled views when they were completed. Both buildings had owners who eventually moved out in favor of better office space elsewhere. The difference was, 20 Exchange was built a few decades after Singer, so it weathered through the changes of the mid-century without becoming vacant. In 1996 it was given landmark status, and was subsequently converted to residential uses. This gave the building a second life, and it exemplifies the proper evolution of the skinny tower archetype. Apartments and condos require much smaller floor plates than commercial does, so conversion works quite well. Had this happened to the Singer Building, no doubt it would still be in existence today, and it would most likely have landmark status as well.

Postcards showing the Singer Building on the left, and 20 Exchange Place on the right. The design and the history of 20 Exchange closely mirrors the story of Singer, but it has a much better ending.

Over time, all skyscrapers become outdated and will require renovation of some kind. In many cases these renovations prove too costly for an owner to undertake, so the tenants move out and the building eventually goes up for sale. This is a crucial moment for any tower, and the examples of the Singer Building and 20 Exchange Place provide the two most likely outcomes. In the case of 20 Exchange Place, it was able to get landmark status, which protected it from demolition. This allowed for a much better outcome than Singer. In the case of the Singer Building, a vital piece of early skyscraper history was lost.

I have no doubt that Lower Manhattan would be a better neighborhood had the Singer Building survived. I also have no doubt it’s remembered more fondly today because it was demolished. There’s a sense of nostalgia for buildings like this, because scenarios exist that could’ve prevented its destruction. It was also built during a time when buildings were designed with care, and weren’t treated like objects in an assembly line. The ornament and sculpture adorning the Singer Building was evidence of the men who designed and built her, and in this sense, she was unique. The U.S. Steel building could’ve been built anywhere, by anyone. That being said, Singer would be a much different building today than it was when it was built. If it wasn’t demolished, the open views it originally provided would now be drowned out by all the taller buildings built since then. It’s position on the skyline would be almost non-existent, much like the nearby Trinity Church. It would most likely need to be converted to a hotel or residential units, and marketed on its location and old-world charm. Still, this sense of nostalgia is fuel for future preservation efforts, and it’s destruction no doubt led to other skyscrapers being granted landmark status as a result.

Check out other posts about demolished architecture here.

[1]: "Forgotten Pioneering". Architectural Forum 106 (April 1957): 117-120.

[2]: "Landmarks: Too Good to Last". Architectural Forum 127 (July–August 1967): 107-108.