The Towers of Svaneti

Illustration of the Svaneti towers, drawn by French illustrator Laurens for the 1881 edition of Le Tour du Monde.

Joseph Campbell once said that you can tell what’s informing a society by what the tallest building is.[1] The illustration above is a perfect example of this. It shows a small village in Svaneti, which is a mountainous region in Georgia dotted with settlements just like this. These highland villages are home to a unique type of tower house, which was borne out of the local history and culture. The Svan people were defending themselves, and they were using verticality to do it.

The region of Svaneti has a turbulent history full of war and conflict. The region has been occupied by myriad foreign armies since antiquity, and a clan-like culture of blood revenge has been commonplace. Throughout the years, the local families learned to defend themselves from external and internal threats, and they did this by building tower houses. These structures allowed a family to seek refuge during times of conflict, and they served three main functions. First, each tower was part-castle, acting as a mini-fortress. Second, each tower was part-watchtower, allowing occupants to view the surrounding landscape. Third, each tower was part-vault, housing a family’s most valuable possessions.

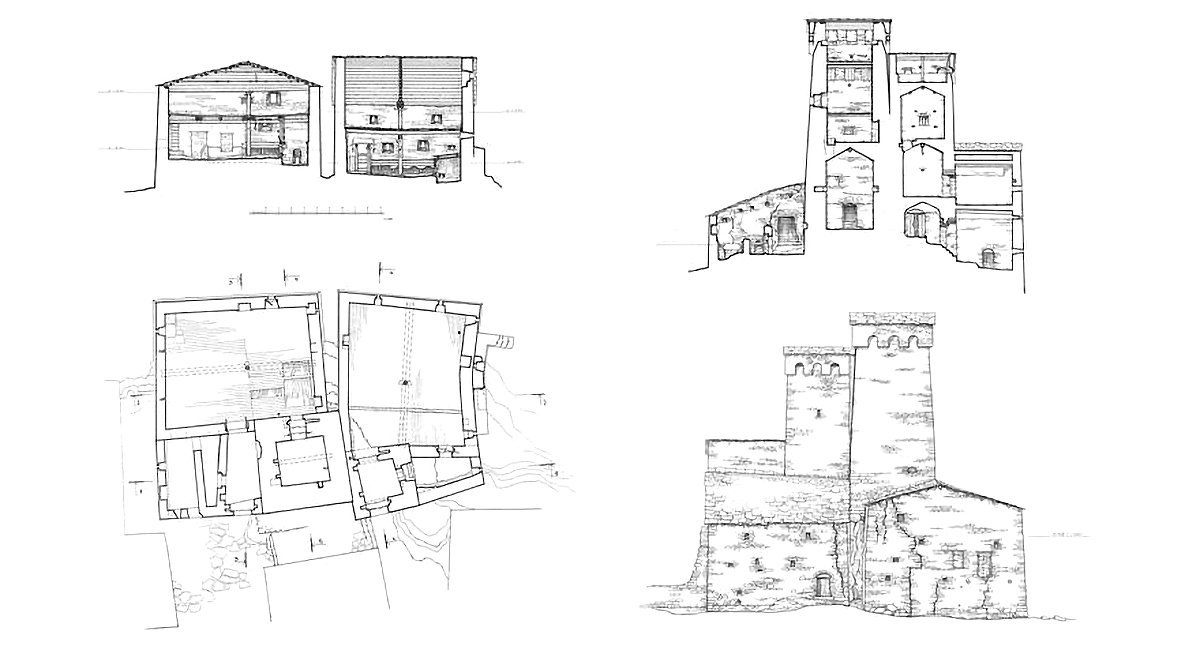

Drawings of a typical Svan tower, showing the interior spaces and wall thicknesses. Drawn as part of an ICOMOS Georgia Study funded by Getty Grants Foundation. Original image source.

A Svaneti Tower is typically between four and six stories tall and is either freestanding or attached to a one or two story dwelling. Pictured here are examples of each. They’re typically four-sided with massive walls that taper from bottom to top. An entrance was usually placed a few meters above ground with a ladder or stair that could be raised up to prevent further entry. Once inside, the tower housed a series of stacked rooms connected with wooden ladders. At the top level is a shallow crown and roof with small openings on each side. These openings, called embrasures, allowed the family to watch over their surroundings or fire weapons from them. They also aided in ventilation and brought light inside.

Drawings of a typical Svan house with two towers. Drawn as part of an ICOMOS Georgia Study funded by Getty Grants Foundation. Original image source.

For the Svan people, height equaled safety. A taller tower house will have better views and will provide better ranges for weaponry. Thus, it will allow a family to better defend itself. It will also contain more space, which is a signal of higher social status. These are all hallmarks of Medieval architecture, and regional examples of tower houses can be found throughout the ancient world. Regardless of location, buildings such as these will always result from turbulent and uncertain times, and verticality will always be part of the defensive strategy.

Check out other posts about verticality and architecture here.

[1]: Campbell, Joseph, and Bill Moyers. The Power of Myth. New York: Anchor Books, 1988. 118-119.