The Montgolfier Brothers and Their Balloons

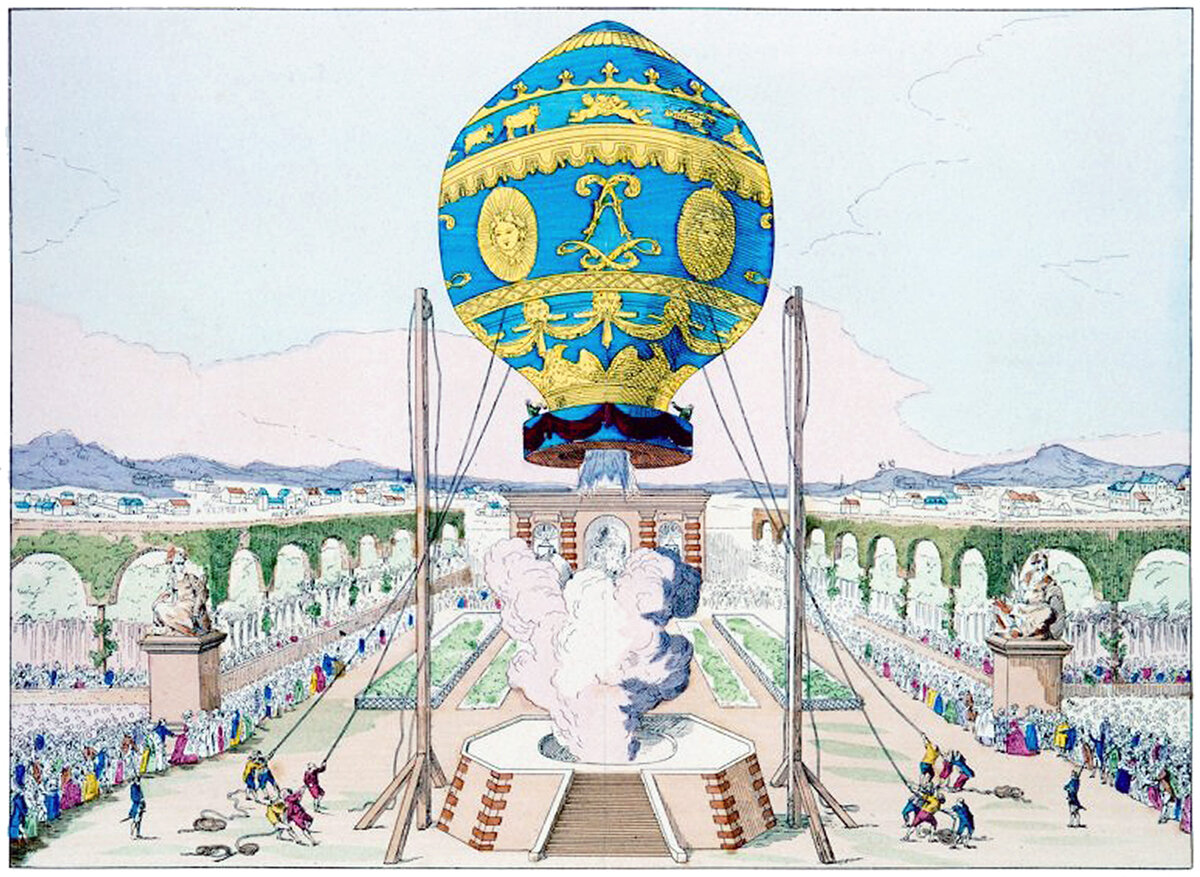

An illustration of the Montgolfier Brothers’ balloon taking off in 1783, in the world’s first successful balloon flight with a human pilot. The drawing is from Gaston Tissandier’s 1887 book Histoire des Ballons.

The Montgolfier Brothers are credited with the first ever successful balloon flight with a human pilot. Pictured above, the flight took place in Paris in 1783. The brothers, Joseph-Michel and Jacques-Étienne, were born into a family of paper manufacturers, but became obsessed with flight after observing clothes drying over an open fire. Their pairing would prove to be well-suited to invention and innovation; Joseph-Michel was dreamer and a visionary, while Jacques-Étienne was a more mild-mannered businessman. Together, they experimented with flight and invented the Montgolfière-style hot-air balloon.

Joseph-Michel was the first to be interested in aeronautics, and after experimenting with hot air inside various enclosures, he recruited his brother to join him. Together, they experimented with larger versions of their balloons, and eventually they made the first public demonstration on 4 June 1783 at Annonay, France. The balloon was made of several large pieces of sackcloth fastened together with buttons. On the exterior, a net of cords held everything together. After taking off, the balloon traveled roughly 2 km (1.25 miles) with an estimated altitude of 1.8 km (5,900 feet). Pictured below is an illustration of the balloon’s launch.

Illustration showing the first public demonstration of the Montgolfier’s balloon. It was an early prototype, without any cargo, but it flew over 2 km (1.25 miles) and caught the attention of Paris, which led to subsequent demonstrations in the capital.

The Annonay demonstration was heard about in Paris, and Jacques-Étienne subsequently traveled to the capital to make further demonstrations. After impressing in Paris, the brothers teamed up with wallpaper manufacturer Jean-Baptiste Réveillon to build larger prototypes that would include living cargo. Their first balloon carried animal cargo, consisting of a sheep, a duck and a rooster. The animals were put on board to test the effects of high altitudes on living beings. The balloon successfully flew on 19 September 1783, which prompted the king to allow flights with human pilots.

The picture at the top of this post shows the Montgolfier’s most famous balloon flight. After the flight with animal cargo, Réveillon designed a wonderfully ornamental balloon, with a deep blue background, accented with red and gold ornament. Pictured below is a more detailed image of the balloon’s design. The balloon flew on 21 November 1783, claiming the first ever free flight with a human pilot. Pilâtre de Rozier, and Marquis d'Arlandes were on board, and they successfully flew for 9 km (5.6 miles) over Paris at roughly 910 meters (3,000 feet) above the city. After the flight, the balloon became a sensation, and it was plastered on all kinds of goods, each made to commemorate the historic event.

Technical drawing of the Montgolfier Brothers’ balloon, which was the first balloon to fly with a human pilot in 1783.

The story of the Montgolfier Brothers and their balloons fits right into the history of human flight. Like so many other pioneers through time, both men came from unrelated backgrounds, but somewhere along the way they became obsessed with flight. It’s a testament to the human need for verticality that the Montgolfier brothers were so interested in flight, and the balloon’s cult-like status after it’s journey is further evidence that the need for verticality lives in all of us.

Read more about other ideas for flying machines here.