Verticality, Part VIII: God versus Ego

The human world becomes as important as the world of God

This chapter is part of a series that compose the main verticality narrative. The full series is located here.

The rise of Christianity in the Western world would have profound effects on the built environment and human culture. Two major threads would combine to influence Early Christian architecture and culture. The first is the architecture of the Ancient Romans, who were already wrestling with verticality. The second is the Book of Genesis and its central theme of heaven (the sky) and hell (the underground). Combine these two, and you get an ongoing battle between God and Ego that would see some of the most impressive structures of all time get built.

We begin the discussion with the Early Christian and Byzantine Empires, who were the first to build upon the Ancient Romans’ struggles with verticality.

Early Christian & Byzantine Empire (circa 330-1260AD)

The early Christians and Byzantines, much like the Ancient Romans, built massive interior spaces in order to externalize their need for verticality. These spaces were built to convey the power of Christianity, and nearly all would be capped by a monumental dome. While the Ancient Romans would typically leave an oculus at the top of their domes, the Early Christians and Byzantines closed them off to the sky.

A section of the original design for Hagia Sophia drawn in 1908 by Wilhelm Lübke & Max Semrau. The building is designed around a central dome, which seems to ‘float’ due to the clerestory windows at its base. Image source.

The most famous Byzantine building, and a perfect example of this evolution is the Hagia Sophia in Istanbul. Built sometime in the fourth century AD, it was constructed as a Christian cathedral, and was designed around a massive central space topped with a closed dome. This dome is important for two reasons. First, it’s closed off to the sky. This signifies that humanity was now satisfied with our versions of heaven on earth, and we no longer needed to directly connect them to the sky. The second is the clerestory band around the base of the dome. This ring of windows brings in natural daylight, which is much brighter than the interior space. The contrast of brightness creates a glowing effect around the windows, enabling the dome to ‘float’ above the structure below. The result is a dome that is of heaven rather than here on earth. We were no longer connecting our interior spaces directly to the sky, but we were still acknowledging the separation between the surface and the sky. The building was both of the surface and of the sky at the same time. Similar structures from this time period include the Hagia Irene, also in Istanbul, the Basilica of San Vitale in Ravenna, the Hosios Loukas Monastery in Greece, and St Mark's Basilica in Venice.

Fifth century Icon of Simeon Stylites the Elder With Simeon Stylites the Younger, showing the men atop their pillars, attempting to get closer to God. Image source.

Another example of cultural verticality from this era is the emergence of stylites. Stylites were Christian ascetics who ascended to the top of tall pillars and spent long periods of time there. Also called pillar hermits, the name stylite comes from the Greek word for column, stylos. These men believed that salvation would come by getting closer to God, and living their lives atop a pillar was the best way of achieving it. The most famous of the stylites was Simeon Stylites the Elder, who lived in the fifth century AD and remained atop his pillar for over thirty-five years until his death.

Though it may seem archaic, stylites still exist today. Although the conditions are less extreme, the inspiration remains the same. In Georgia, a monk named Maxime Qavtaradze lives atop Katskhi Pillar in a small monastery, and only comes down to the surface twice a week. For him, the top of the pillar is ‘where land meets sky...it is up here in the silence that you can feel God's presence.’[1]

The two examples discussed here will become themes throughout our subsequent history with verticality. In the Hagia Sophia example, we were attempting to construct a monumental space that represented the meeting of heaven and earth. The experience gained is meant to be on the surface and looking up. In the second example of the stylites, the act of raising the human body up above the surface is the focus, meaning the experience gained is above the surface looking down. The former will be further explored throughout the rest of this chapter, while the latter will pop back up in the next chapter and will ultimately become the focus of our efforts to escape the surface.

Romanesque Architecture (circa 750-1200AD)

Much like Early Christian and Byzantine architecture, Romanesque architecture was directly influenced by the Ancient Romans, however these buildings took the concept of heaven on earth further than the Early Christians and Byzantines before them. Romanesque interiors no longer connect directly to the sky, and don’t create a separation between the surface and the sky.

A photo of Maria Laach Abbey, taken in the early 20th century by Verlag von Stengel & Co.. The building features turrets and steeples, which serve to draw the eye upwards and point to the sky through their form. Image ©️ Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. Image source.

Take the Maria Laach Abbey for example. It epitomizes the Romanesque struggle for verticality through both its interior and exterior design. The interior, much like the aforementioned buildings, is attempting to create heaven on earth, but here the vaults are solid, and the space lacks a separation between earth and sky. The vaults don’t ‘float’ like the dome of Hagia Sophia, but rather spring from the columns in a continuous manner, creating a cohesive interior space. We no longer needed to separate the surface and the sky within our monumental spaces; our recreations of heaven were just as good as heaven itself. The building’s exterior also incorporates verticality through its form and ornament. Tower forms create vertical expressions, while steeples point upward to the sky, as if to signify that the building is referencing the heavens above. Ornament enhances this reading, with pinnacles atop each steeple further pointing upwards.

Another notable example is the Leaning Tower of Pisa. Built as a bell tower for the Cathedral of Pisa, the structure has become famous for its battle with gravity, resulting in a precarious four-degree lean. It’s also notable for its architectural design, which exhibits a stacking of similar floors throughout the shaft of the tower. It also marks the emergence of the campanile, or bell tower, as an architectural form meant to mark the importance of a place through verticality. These towers rise high to become more visible to the surrounding landscape, which is a practice that can be tied all the way back to the menhirs discussed in the Archetypes chapter.

Romanesque Architecture marks the first examples of buildings that recreate heaven on earth without the need to connect to the actual heavens. These buildings can be seen as a bridge between the Ancient Romans and the Gothic cathedrals of the Middle Ages, which we will look at next. The nascent ideas encapsulated in Romanesque architecture would soon explode into the rampant verticality of Gothic Architecture.

Gothic and Medieval Architecture (circa 1100-1550AD)

Gothic architecture is characterized by the Gothic arch, flying buttresses and ribbed vaulting. Each of these elements serves to help draw the eye upwards toward the heavens. These buildings build upon Romanesque architectural traditions, and incorporate rampant verticality on the exterior and interior.

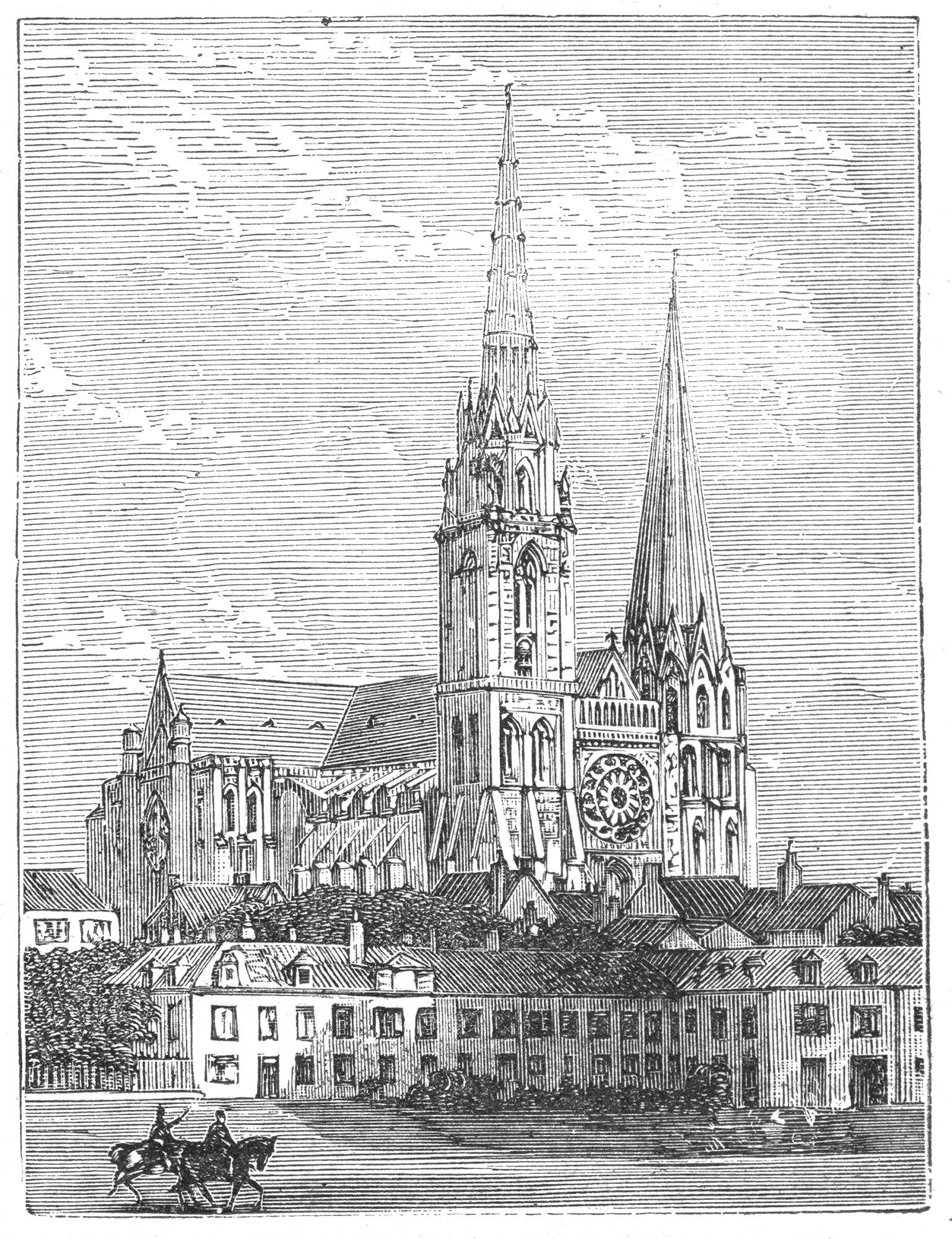

Drawing of Chartres Cathedral towering over the surrounding town. The building was creating a landmark out of its place and pointing up to the sky through its architecture. Drawing from the Nouveau Dictionnaire Encyclopédique Universel Illustré from 1885.

Chartres Cathedral in France provides a perfect example. The exterior design and ornament showcases myriad details that point upward, including steeples, buttresses, pointed arches and pinnacles. At first glance, the building seems to be reaching upwards in an effort to reach the heavens. The bell towers and steeples tower over the surrounding town, creating a landmark that can be seen for great distances. On the interior, the nave is stretched upward and the column lines push up into the ribbed vaults, creating a space that draws the eye upward toward the heavens. Much like Romanesque buildings before it, the interior is cut off from the sky, creating a dichotomy between the exterior and interior. The entire building points up to the heavens, but simultaneously cuts itself off from them. Other similar examples include The Notre-Dame de Paris, Laon Cathedral, Reims Cathedral, Salisbury Cathedral, the Abbey of Saint-Étienne in Caen and the Sainte-Chapelle in Paris.

Later Gothic architecture would take the ideals of Chartres and exhibit rampant verticality to the extreme. Take Milan Cathedral for example. The exterior is a cacophony of vertical elements; every opportunity to design a detail that points upward is taken. There is no singular vertical element, such as a steeple or bell tower, but rather a veritable forest of buttresses, pointed arches and pinnacles. Each element is stretched vertically in order to maximize the reach of the collective. On the interior, The same dichotomy mentioned above exists. The exterior does all it can to point up toward the heavens, but the interior closes itself off to them. It’s almost as if humanity was showing that we could recreate heaven on earth, but we were still tentative about severing the link completely.

Elsewhere in the Gothic world, secular buildings started to get more attention, as Ego began to emerge as a counterpoint to the needs of God. Cities and towns began to construct tall buildings in an effort to announce their power and wealth to the surrounding landscape. These buildings took cues from religious landmarks, such as bell towers and turrets, to create singular expressions of verticality. The city of Bruges, Belgium built the Belfry of Bruges on their main square. Brussels also built a major tower on their main square as part of their town hall. London’s Parliament building, with the iconic Big Ben clock tower, is a fine example of English Gothic. San Gimignano and Bologna, both in Italy, saw the construction of myriad tower-houses by their wealthy residents, built most likely for defense against attack or as a show of wealth to other rich families. Similar tower-houses can be found in the Georgian town of Chazhashi.

Gothic Architecture dominated the Western world throughout the Dark Ages, and saw an explosion of verticality on the most ambitious works of architecture. With the Enlightenment and the Renaissance, however, major works of architecture would shed this rampant verticality in favor of singular gestures, seeing the pendulum shift farther towards Ego in the battle between God and Ego.

Renaissance and Baroque Architecture (circa 1325-1750AD)

With the Renaissance came an explosion of architectural innovations, and new approaches to verticality. The rampant verticality of Gothic buildings would be replaced by larger, more singular expressions of height. Where Gothic architecture took pains to point up to the heavens, Renaissance architecture would shed this deference and fully commit to the heaven-on-earth mantra.

Section through Florence Cathedral, with its massive dome, designed by designed by Filippo Brunelleschi. The dome represents a singular expression of Heaven on earth that is just as good as Heaven itself.

The Florence Cathedral epitomizes this transition. The building’s exterior no longer points up to heaven with myriad details. Instead, it showcases a singular, monumental expression of height: the dome. The building commands the skyline of Florence, and makes a landmark out of its location. On the interior, many similarities to Gothic cathedrals can be found, but the dome is the main focus. This allows the heaven-on-earth metaphor to fully ground itself on the surface, without a connection to the actual heavens. The transition is complete; our recreations of heaven on earth are just as important as heaven itself. Other similar structures include St. Peter’s Basilica and the Tempietto, both in Rome, the Sorbonne Chapel and Chapel of Les Invalides, both in Paris, St. Paul’s Cathedral in London, and Santa Maria della Salute in Venice

We began this chapter with a look at Early Christian architecture, which was completely focused on the needs of God. Throughout the spread of the Western world, God slowly lost the foothold in the battle with Ego, and the Renaissance would ultimately be the last great era of God. At the end of the Renaissance, architectural masterworks were no longer dominated by religious buildings. Royal palaces and civic buildings gain prominence, and as societies gain wealth and technology advances, focus shifts further to the needs of Ego and away from the needs of God. As we’ll see in the following chapter, the Industrial Revolution would precipitate the shift to Ego over God, and the built environment would reflect that.

Keep reading: Verticality, Part IX: Man Upends God

[1]: Nolan, Steve. "Getting Closer to God: Meet the Monk Who Lives a Life of Virtual Solitude on Top of a 131ft Pillar and Has to Have Food Winched up to Him by His Followers." Daily Mail, September 5, 2013.