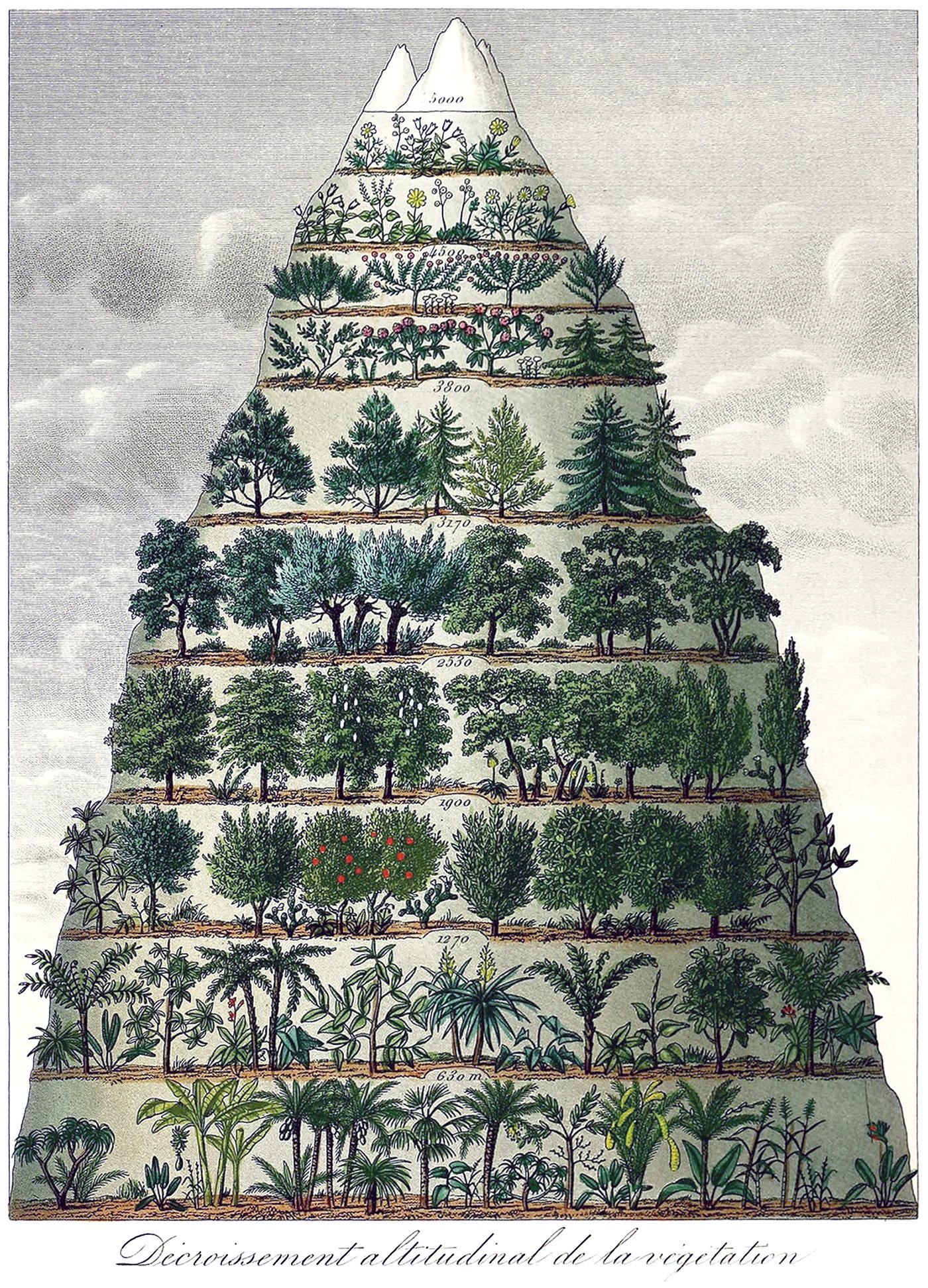

The Altitudinal Decrease in Vegetation

Illustration from 1860 by Jean-Augustin Barral showing altitudinal zonation and its effect on vegetation.

Pictured above is an illustration from the 1860s by Jean-Augustin Barral, titled Décroissement Altitudinal de la Végétation, which is French for The Altitudinal Decrease in Vegetation. It’s a beautiful work that attempts to categorize vegetation types by elevation, which is known as altitudinal zonation. Barral gets the overall concept correct, but we now know the details to be much more nuanced and complex than his drawing suggests.

I’ve previously written about altitudinal zonation and how the physical environment changes as one ascends away from sea level. In that piece, I explored earth’s vertical zones and pointed out a few key factors that make altitudinal zonation so difficult to predict. Two of those factors are present here. First, Barral draws horizontal layers with specific elevations attached to them. This was the thinking in the 1860s, but we now know it to be incorrect. Our physical environment is wonderfully diverse and complex, and these layers will be much more varied throughout the world than the drawing suggests. In some places, the same vegetation can survive at much higher elevations for a variety of reasons. For example, hot and humid climates will be able to support much more diverse vegetation at higher elevations than cooler climates can.

Second, the layers are not flat. They typically slant from north to south because of the sun. In the northern hemisphere, the south face of a mountain will receive much more sun than the north face, which leads to more vegetation at higher elevations.

One thing Barral nails is the decreasing diversity and size of vegetation as one ascends. In general, lower elevations can support lush forests and varied ecosystems, while higher elevations can only support smaller and very specialized species. This dynamism is one reason why mountains are such special places. A world of different environments can coexist on a single mountain, so that a climb to the top can be like a trip from the equator to the poles.

Check out other posts about mountains and verticality here.