Jules Verne’s Clipper of the Clouds

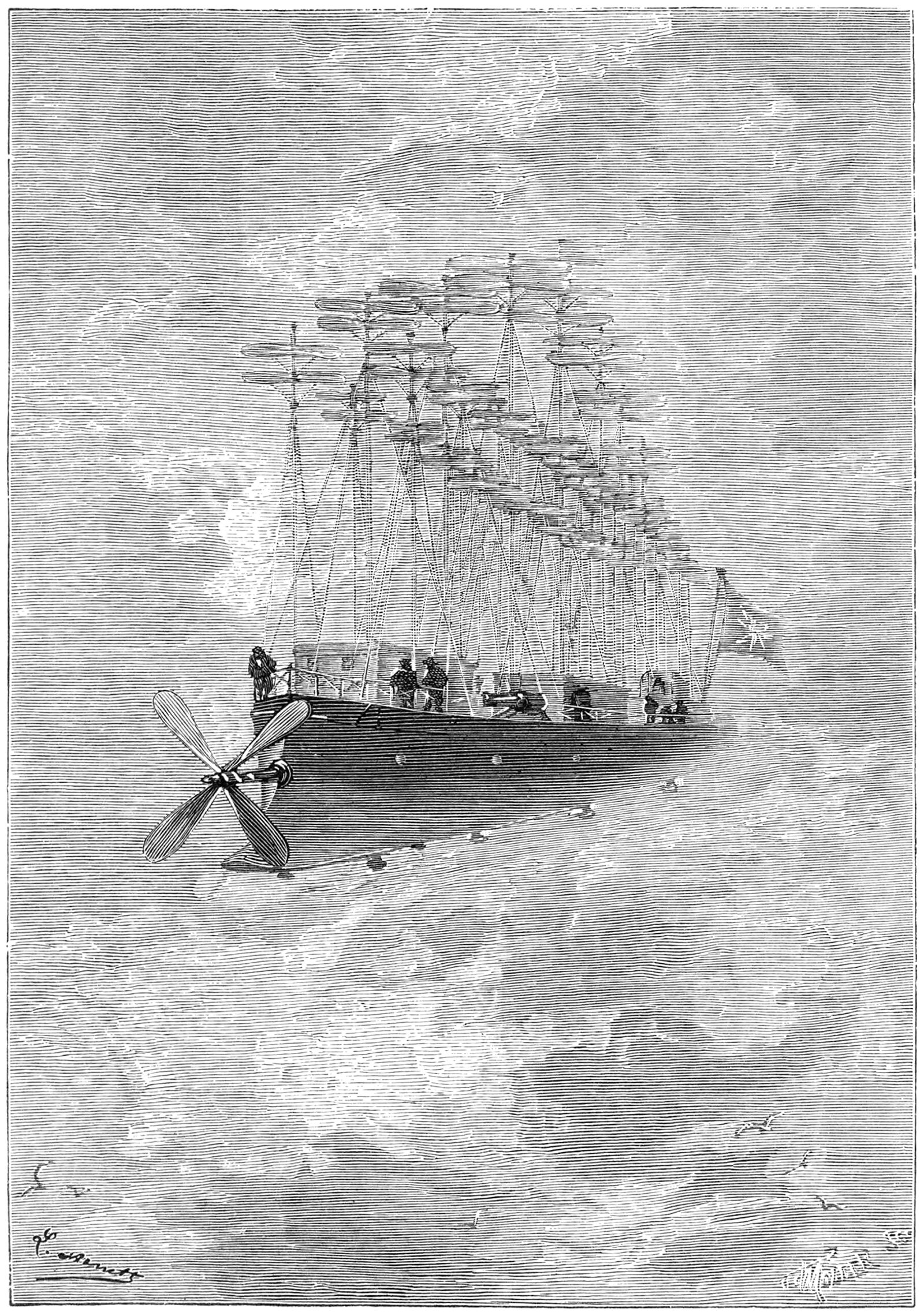

Illustration by Léon Benett showing the Clipper of the Clouds from Jules Vernes’ novel of the same name.

Fiction has a way of reflecting reality. Pictured above is an illustration from Jules Verne’s novel Robur the Conqueror, sometimes called The Clipper of the Clouds, published in 1886. It shows a fictional flying machine called the Albatross, which was built by the novel’s titular character. Throughout the story, Verne explores the nature of flight, its effects on humanity, and the general sense of public awe in the early days of flying machines. There’s also an undertone of the God versus Ego struggle that is central to the verticality narrative.

The novel begins with the appearance of black flags appearing at the top of various tall landmarks around the world. These include the Great Pyramid of Giza, The Eiffel Tower in Paris, and the Statue of Liberty in New York, among others. There is no evidence of how the flags got there, but it’s soon revealed to the reader that the brilliant inventor and adventurer Robur is responsible. He’s built a flying machine called the Albatross, which gave him easy access to the aforementioned high places. His choice to place his flags at the highest points around is significant for two reasons. First, he only places flags on manmade landmarks. This is to acknowledge the previous accomplishments of humanity. Second, he’s using verticality to show his dominance of the skies. By placing flags at these high points, he’s demonstrating the power of controlled flight and how it provides easy access to hard-to-reach places.

Robur then makes an appearance at a meeting of the Weldon Institute in Philadelphia, which is a fictional club dedicated to the pursuit of human flight. The members believe heavier-than-air flying machines are unfeasible, and they have plans to build a lighter-than-air flying machine called the Go-Ahead. This debate reflects the real-world history of flight that was developing at the time. Lighter-than-air machines were the first to achieve flight and they were fairly common at the time of publishing, but heavier-than-air flight, though more difficult to achieve, was seen as a purer form of flight and was still being pursued by myriad individuals. Robur declares the superiority of heavier-than-air flight to the club members, who become incensed. He’s subsequently kicked out of the club, but returns in the night to kidnap three key members and bring them aboard the Albatross.

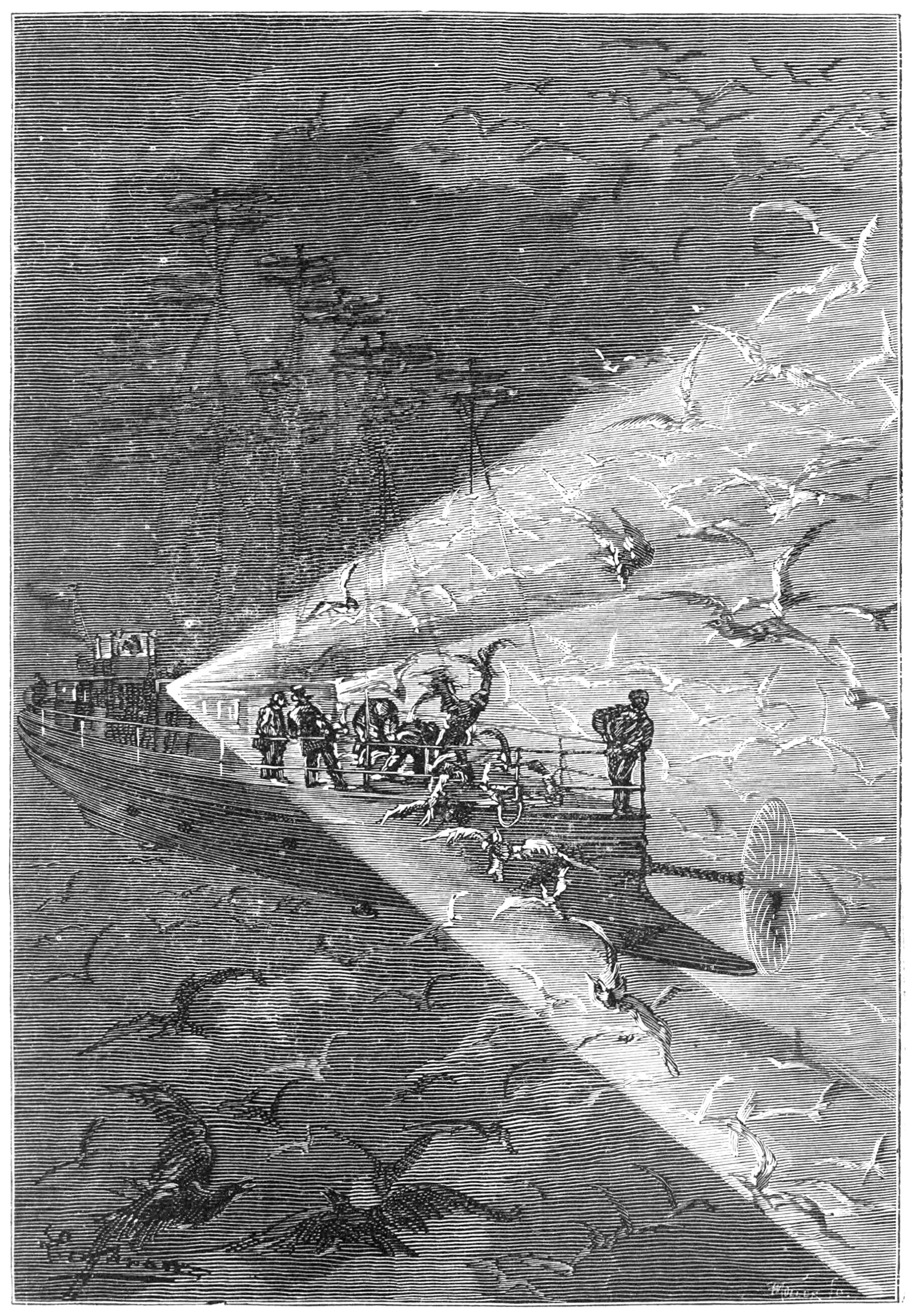

Illustration by Léon Benett showing the Clipper of the Clouds from Jules Vernes’ novel of the same name.

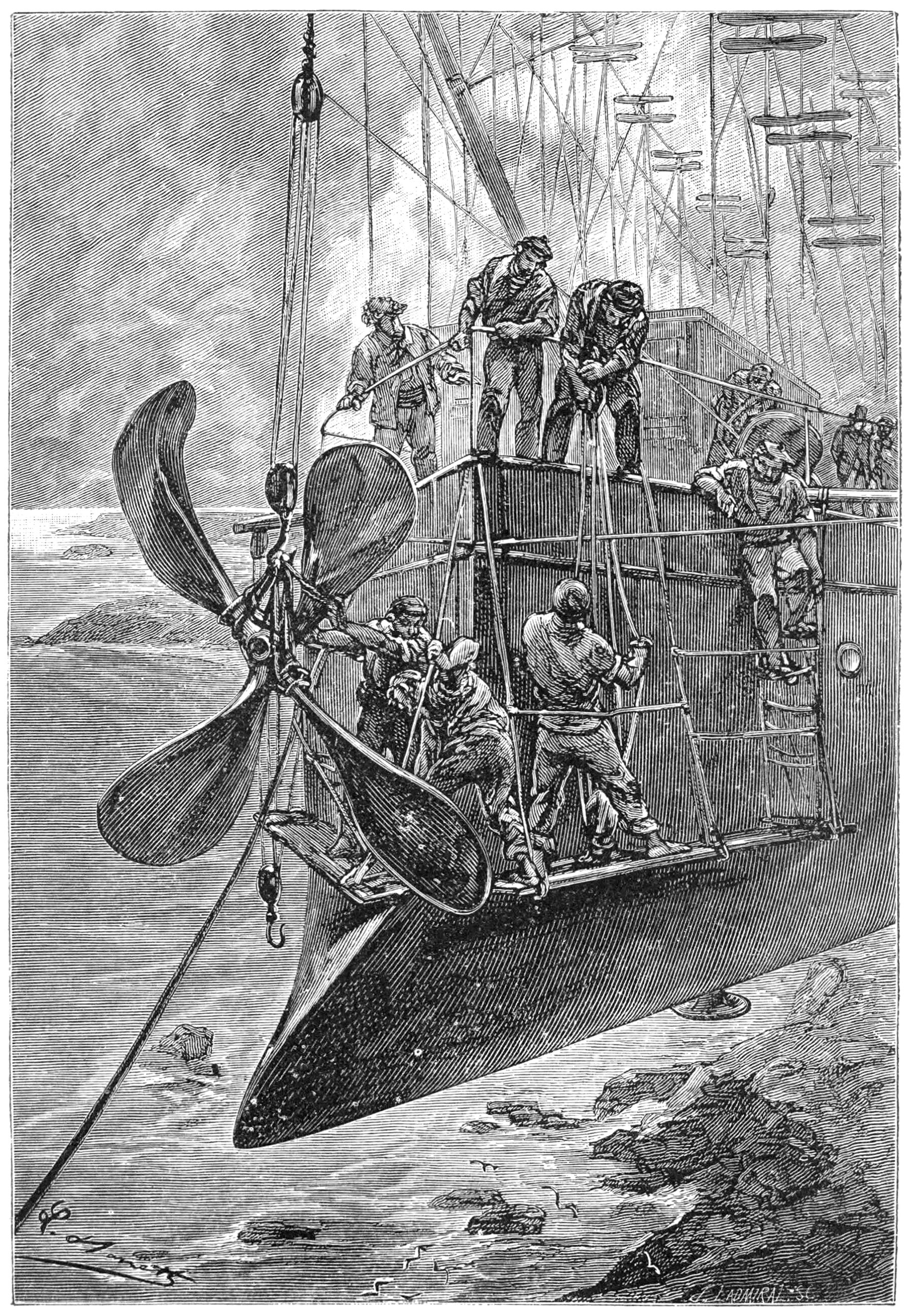

While aboard the ship, the club members learn how it works. Above the main deck are dozens of rotors attached to vertical poles. These rotors generate lift and allow the craft to ascend and descend. Large vertical propellers at the front and the rear provide directional thrust, and combined with the rotors the craft achieves controlled flight. Robur then takes the club members on a trip around the world in three weeks. This impresses them, but they refuse to outwardly admit the superiority of the Albatross. Instead, they form a plan to blow it up and escape.

While docked for repairs after circling the globe, the club members light some explosives and make their escape. The explosion destroys the Albatross and the club members make their way back to Philadelphia. They keep quiet about the superiority of Robur’s craft, and instead they update their designs for the Go-Ahead to include a few ideas from the Albatross.

Some time passes, and the new Go-Ahead gets built with the modifications from the Albatross. On its maiden flight, a large crowd gathers to watch it fly. After successfully demonstrating its flying capabilities, Robur flies in with his Albatross. It’s revealed that the explosion damaged the ship but didn’t destroy it completely, and the crew was able to rebuild it. After flying around a bit, the crowd sees the superiority of the Albatross as a flying machine. Not to be outdone, the Go-Ahead flies upwards until its gas bag ruptures, sending it into free-fall. The crew of the Albatross fly beside the falling ship and save its crew before it crashes to the ground, leaving the crowd in awe.

Robur then addresses the crowd, stating that mankind isn’t ready for heavier-than-air flight, and he would return in the future to reveal his secrets. The crew of the Go-Ahead were then publicly ridiculed for lying about their flying machine, and thus the story ends.

Illustration by Léon Benett showing the Clipper of the Clouds from Jules Vernes’ novel of the same name.

Throughout the story, Verne is tapping into real-life themes and exploring the philosophy of flight. The debate between lighter-than-air and heavier-than-air machines was a real debate going on at the time, with the latter still being pursued. Aside from that, Robur’s declaration that mankind wasn’t ready for heavier-than-air flight has undertones of the Greek myth of Prometheus. As the story goes, Prometheus stole fire from the gods and gave it to humanity. He was then eternally punished by Zeus, much like the club members were. Robur acts as a kind of Zeus here, declaring humans unfit for such technology and indirectly punishing the club members for stealing his technology. This also relates to the struggle between God and Ego from the main verticality narrative. In this case, Robur represents God and the club members represent Ego. In a way, Verne is exploring what it means for humans to fly, and the power that flight gives to those who achieve it.

Check out other posts about other examples of verticality from literature.