Welcome to On Verticality. This blog explores the innate human need to escape the surface of the earth, and our struggles to do so throughout history. If you’re new here, a good place to start is the Theory of Verticality section or the Introduction to Verticality. If you want to receive updates on what’s new with the blog, you can use the Subscribe page to sign up. Thanks for visiting!

Click to filter posts by the three main subjects for the blog : Architecture, Flight and Mountains.

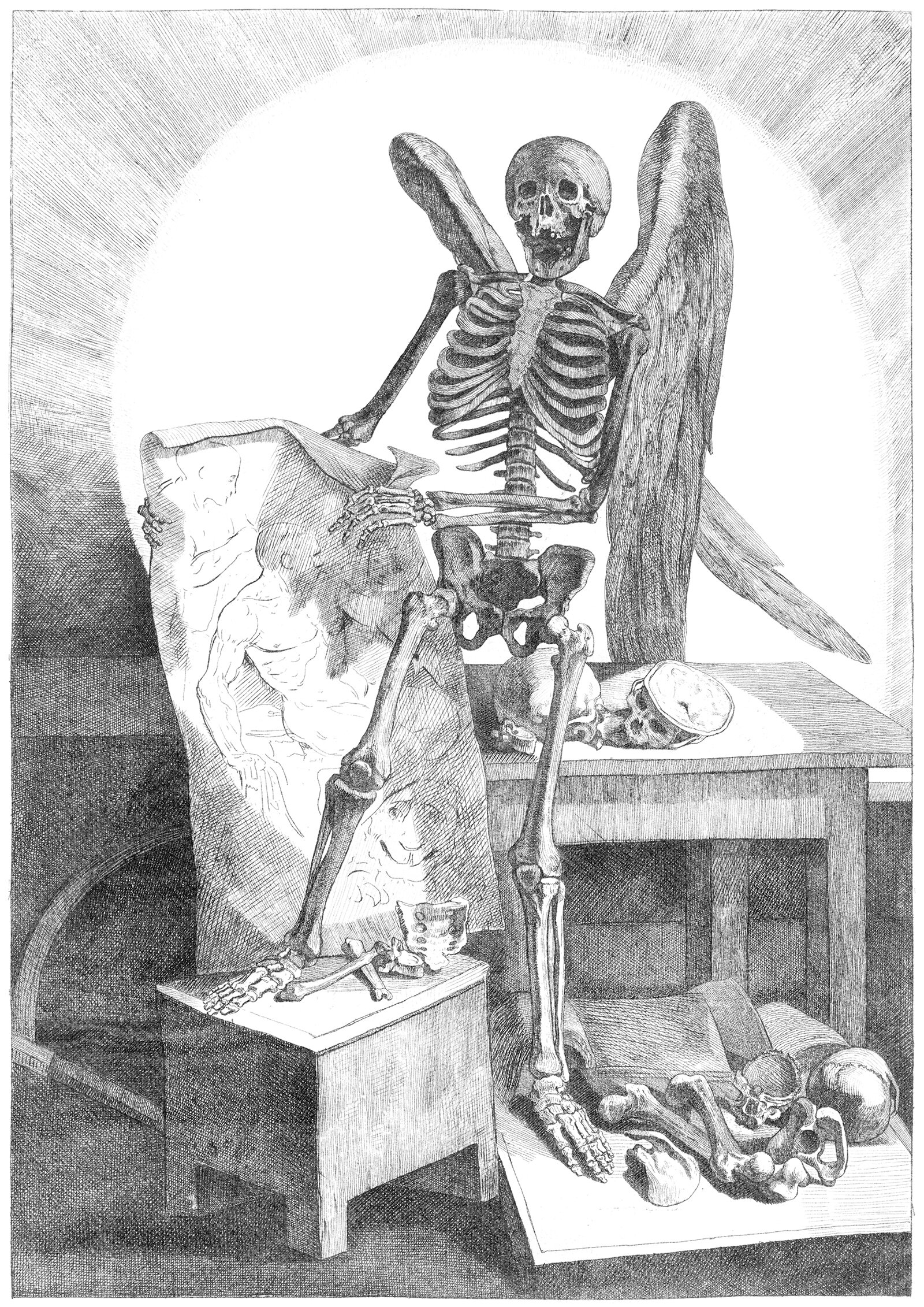

The Human Body and Flight : Why We Can’t Fly

The ability to fly is something that’s been on the human mind since time immemorial. We see birds and other creatures flying through the air, and we seek to fly as they do. We dream about it, and we’ve thought up myriad examples of human-like characters throughout our legends and myths who can fly. For all our hoping, however, it’s impossible for us to fly under our own strength. Let’s take a closer look at why this is true.

“There is a kind of supernatural beauty in these mountainous prospects which charms both the senses and the minds into a forgetfulness of oneself and of everything in the world.”

-Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Genevan philosopher and writer, 1712-1778.

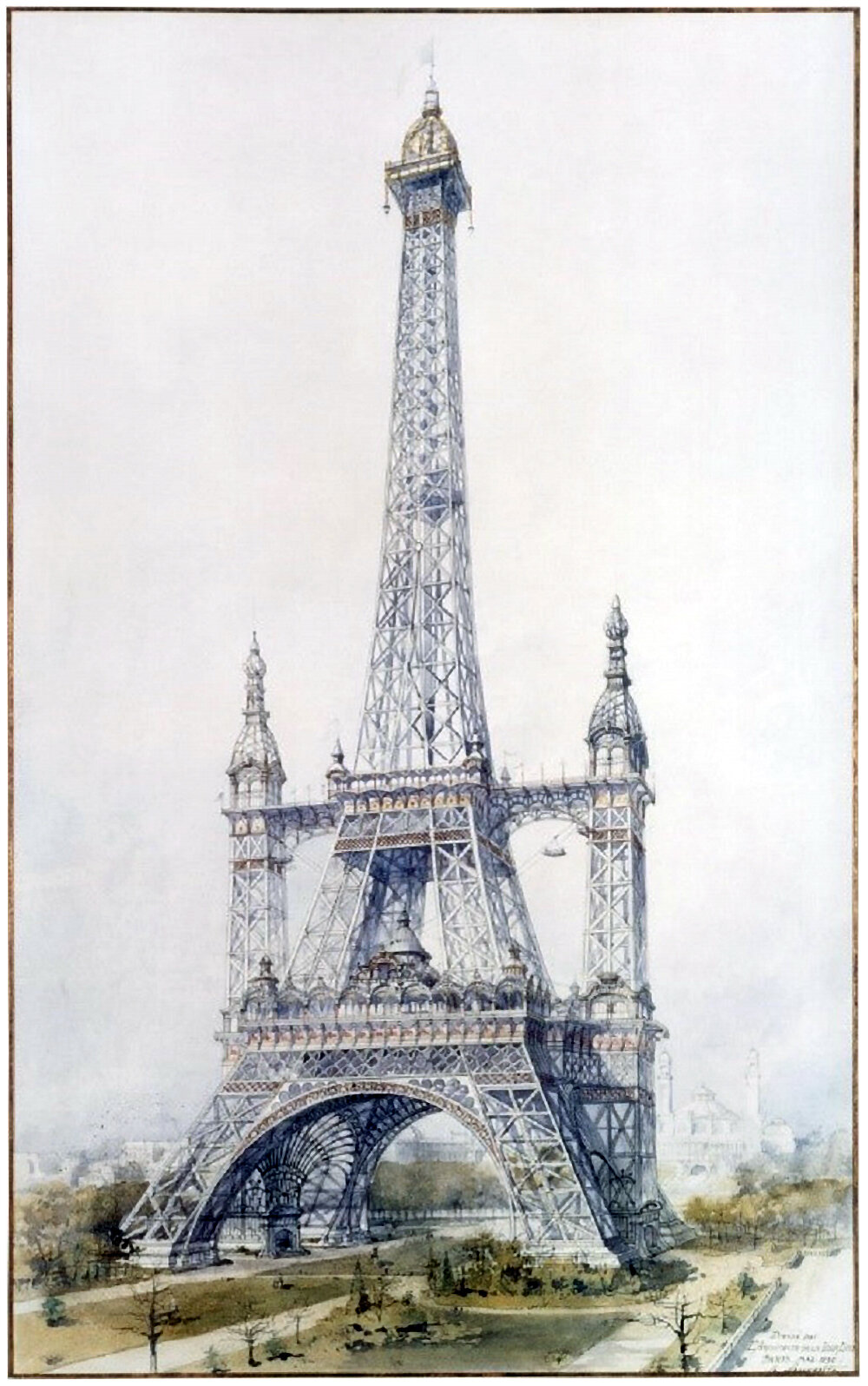

Alternate Realities : The Eiffel Tower

There’s an interesting subtext to unbuilt projects throughout the history of architecture. Unbuilt additions to existing buildings are the most intriguing, because they respond to an existing mind-scape rather than create a new one. The above illustration is a perfect example of this. It shows a preliminary design for the Eiffel Tower in Paris, drawn by French architect Stephen Sauvestre.

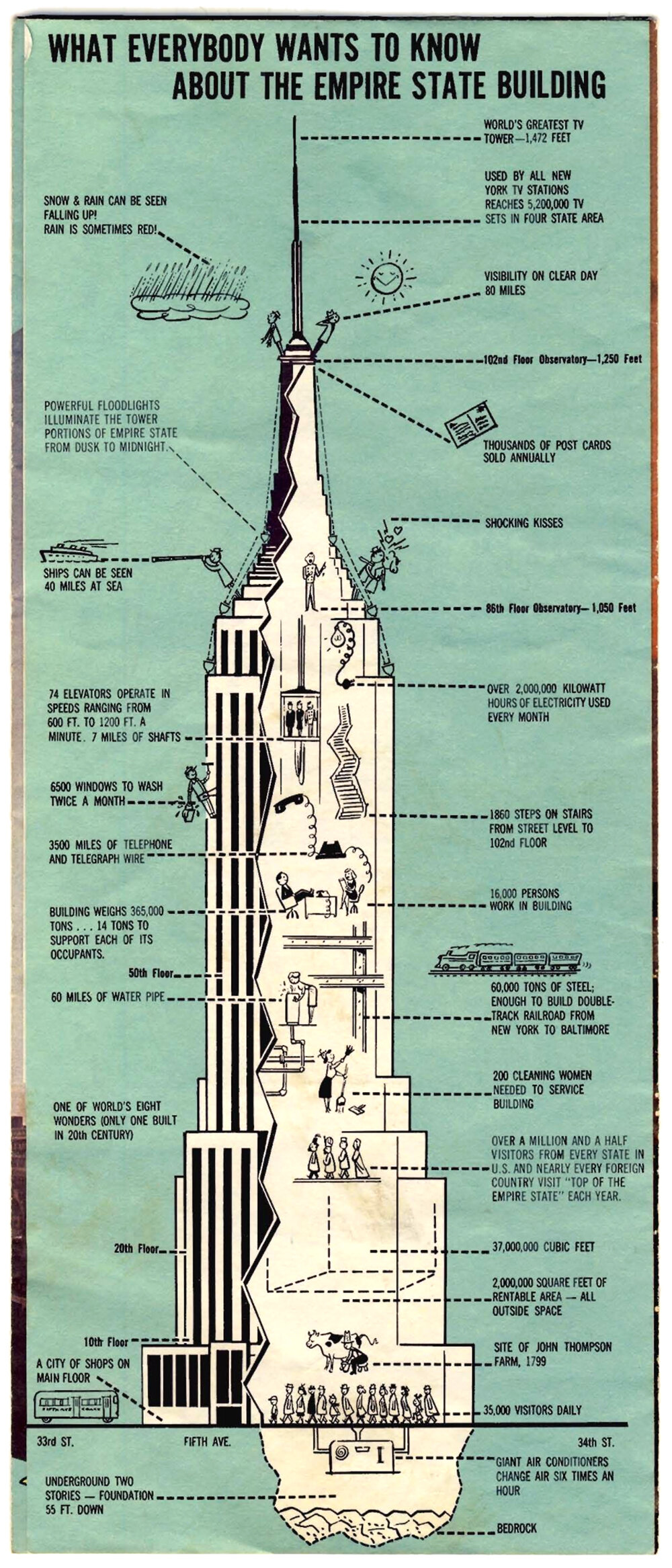

What Everybody Wants To Know About The Empire State Building

Only the most famous and iconic buildings of the world get their own marketing. The Empire State Building in New York City is one of these, and the brochure pictured above is a fantastic little bit of marketing for the tower. I don’t know when it was made or where it was sold, but given the television antenna at the summit, which was installed in 1965, it’s probably from the late 1960’s or 70’s.

The Myth of Wayland the Smith

Throughout the history of myths and legends, there are myriad stories that are shared or borrowed from earlier sources, then re-named and adjusted for a different culture. Certain themes repeat themselves throughout the ancient world, and those that resonate most effectively will endure over time and evolve alongside the cultures they exist in. The myth of Wayland the Smith is one of these.

“As its basic fact and most critical element, it is structure that is at the heart of the tall building’s design.”

-Ada Louise Huxtable, American architecture critic, 1921-2013

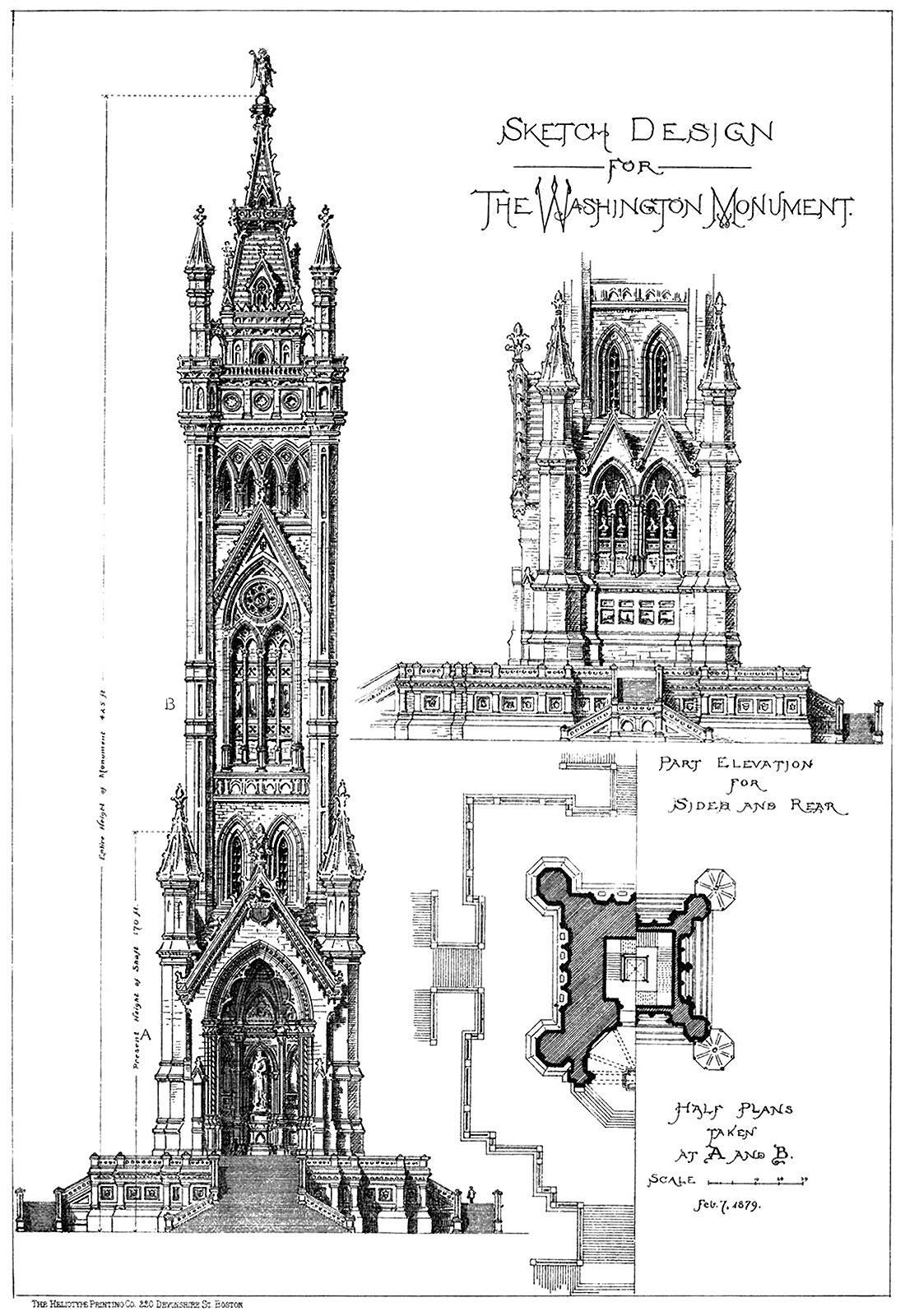

A Sketch Design for the Washington Monument

The above illustration originally appeared in American Architect and Building News, and was submitted to the publication by an architecture student. Curiously, the student is not named, and is just called ‘the author’. The student uses ‘the Gothic treatment’ for the design, which is wonderfully detailed, in stark contrast with the minimalist design that eventually got built.

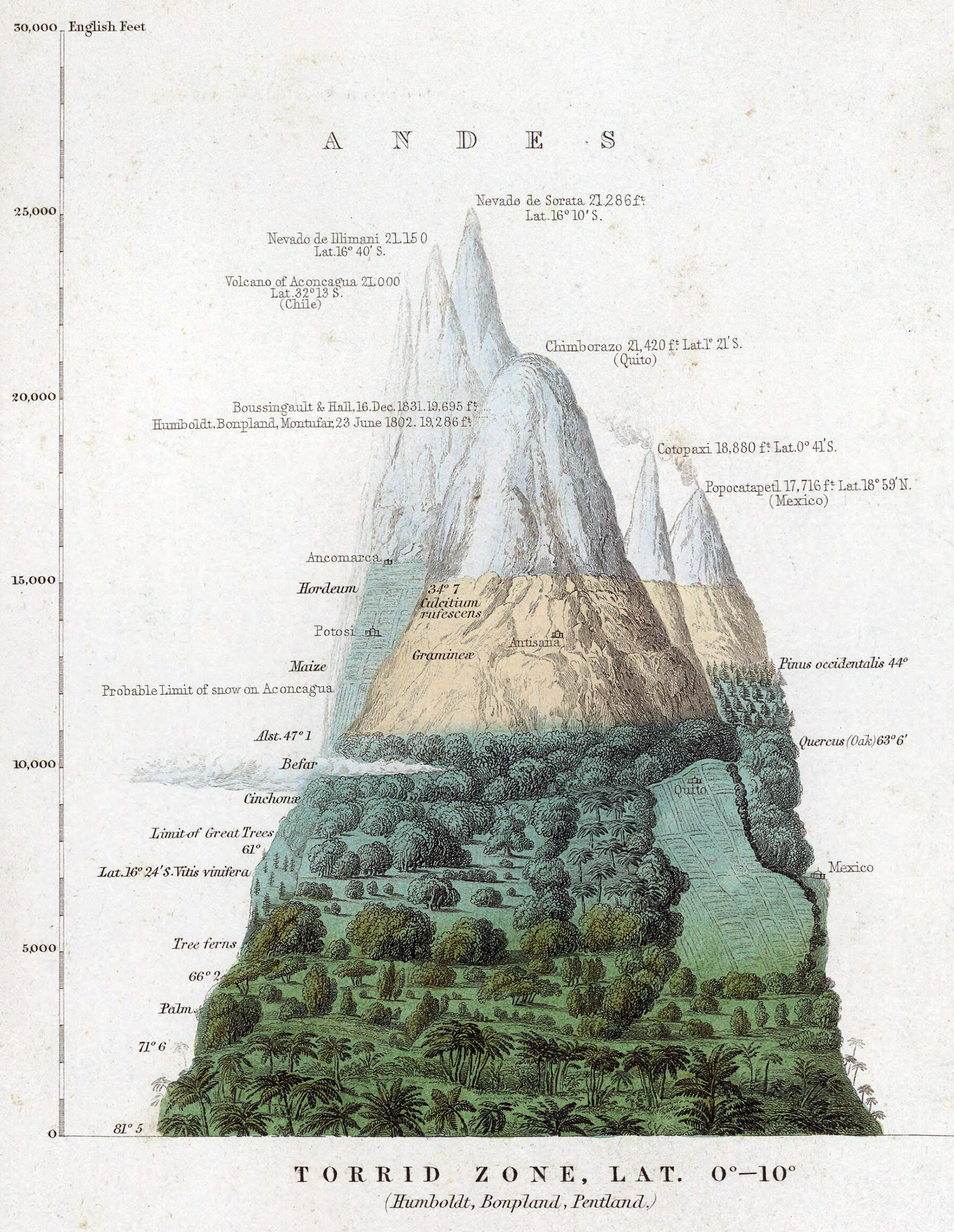

Altitudinal Zonation : Mountains and Verticality

The earth’s atmosphere is defined by vertical gradients. As one rises, the air thins out, humidity decreases, and temperatures drop. It’s why we get altitude sickness when we travel to high places, and it’s why the tops of very high mountains are snow-capped. These vertical gradients are defined by altitudinal zonation.

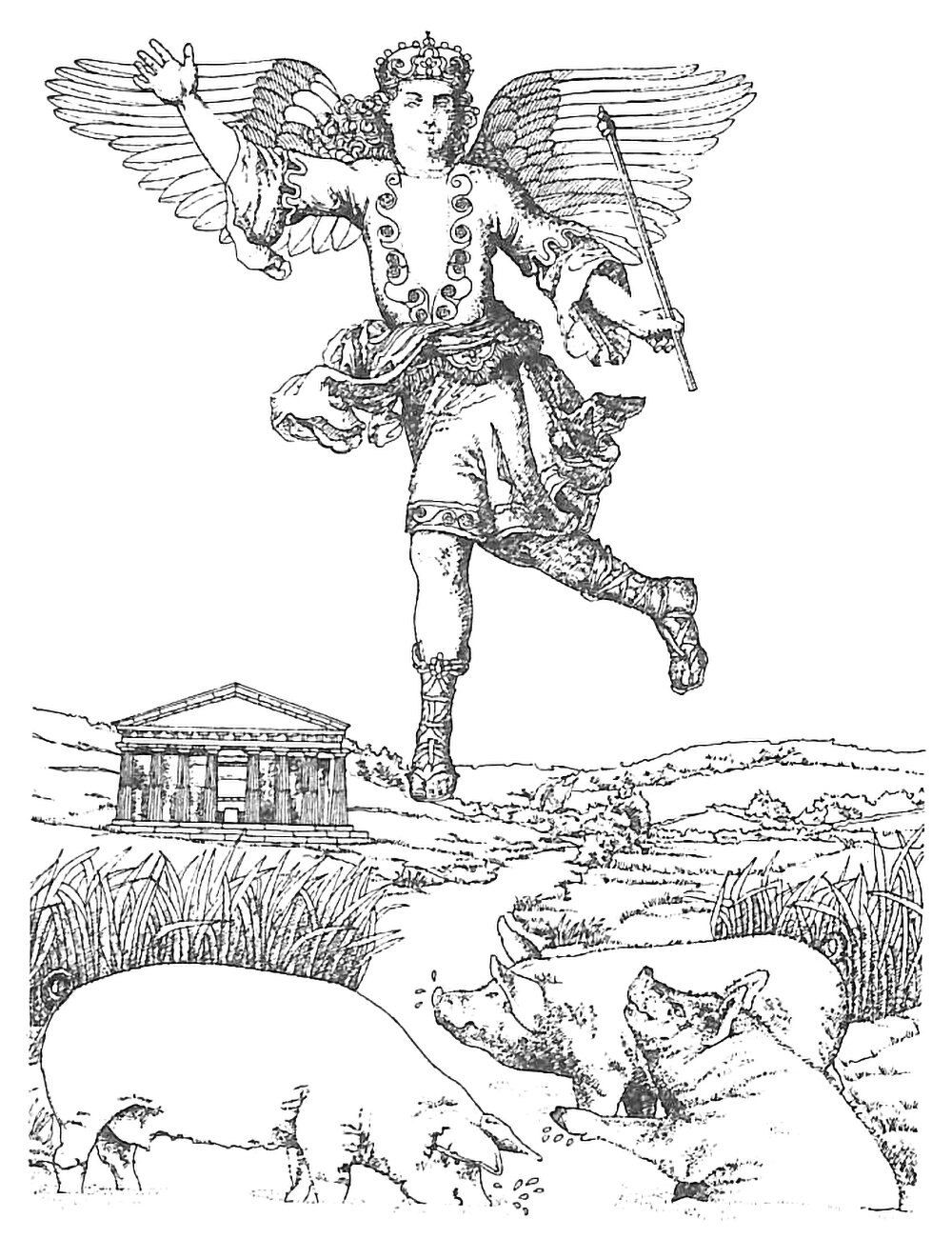

King Bladud and the Myth of the Flying Man

Legends have a way of expanding through time. They exist in the collective consciousness of the people who believe them, and the ones that endure usually grow and evolve alongside the cultures and civilizations they exist in. Take the myth of King Bladud, for example. Over time his story has expanded and endured. This is because he made an attempt to fly.

“[In the mountains], the highest parts of the loftiest peaks seem to be above the laws that rule our world below, as if they belonged to another sphere.”

-Conrad Gesner, Swiss physician and naturalist, 1516-1565.

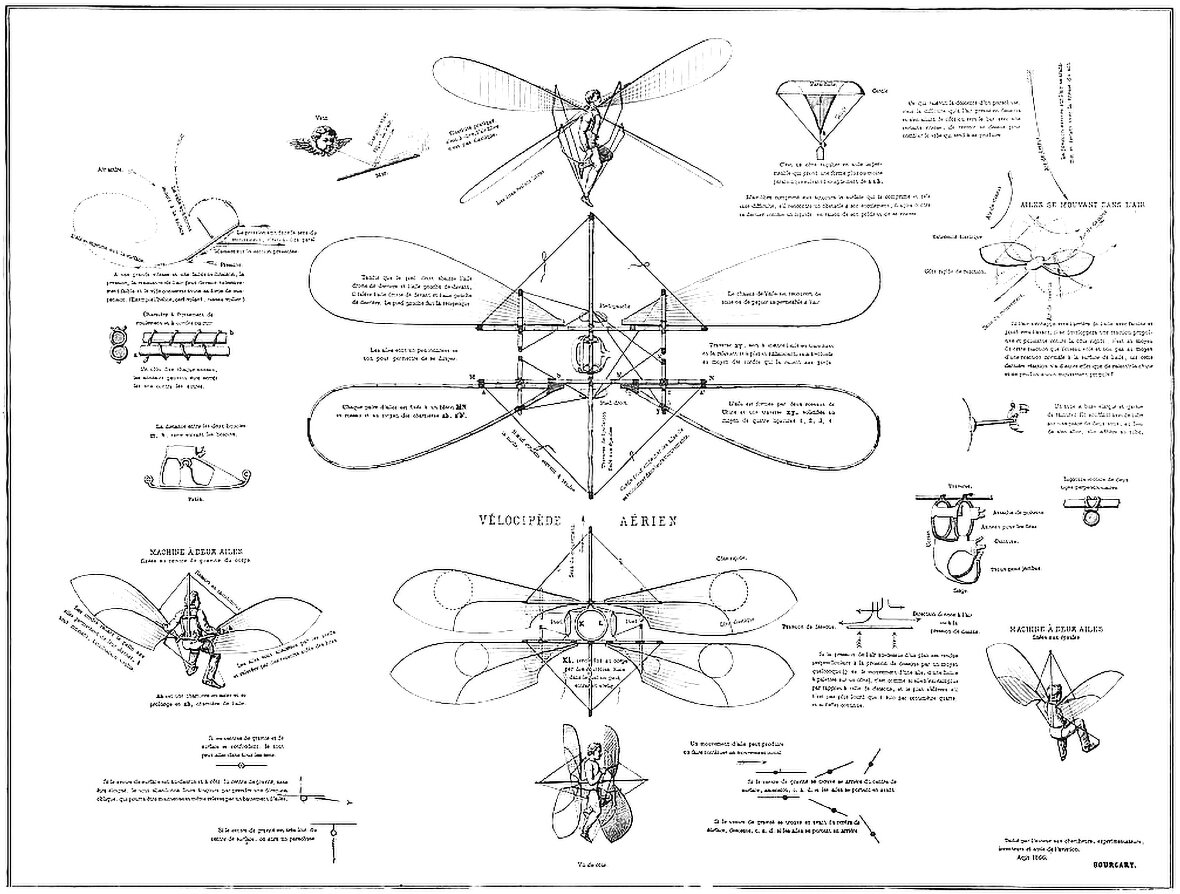

Jean Jacques Bourcart’s Ornithopter

Pictured above is a series of studies for a flying machine, proposed in 1866 by Jean Jacques Bourcart. Titled Vélocipède Aérien, the drawings show variations on an ornithopter design, in which a human pilot flaps the wings of the craft in order to fly. The subtitle of the illustration reveals that these are studies, tests and inventions which, without solving the problem of aviation, have nevertheless given interesting and encouraging results to the author.

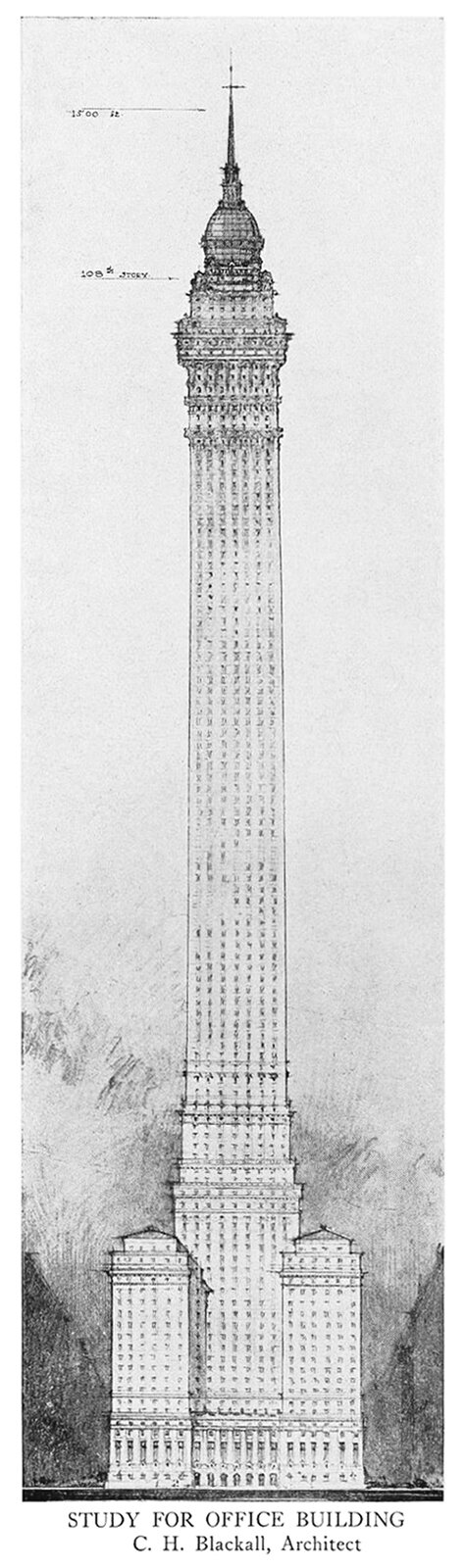

Clarence H. Blackall’s Study for an Office Building

The above illustration originally appeared in an exhibition for the Boston Architectural Club in 1912. The subsequently published yearbook containing the drawing gives no context or background, just the cryptic title Study for Office Building and the architect’s name, Clarence H. Blackall.

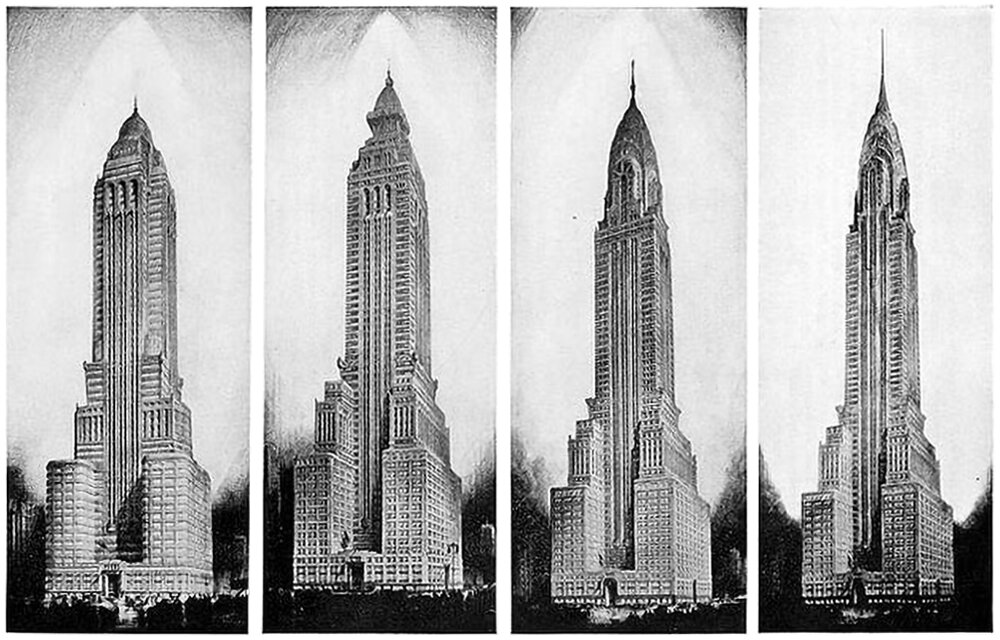

Alternate Realities : The Chrysler Building

The design process is never-ending. The only reason there’s an end is because something needs to get built, and it usually needs to happen quickly. It’s like a film, and the built result is like a snapshot from somewhere near the end of the film. .e image for example, showing. The above illustration is a good example. It four proposed designs for the Chrysler Building in New York.

“The skyscraper is Orwellian or Olympian, depending on how you look at it.”

-Ada Louise Huxtable, American architecture critic, 1921-2013.

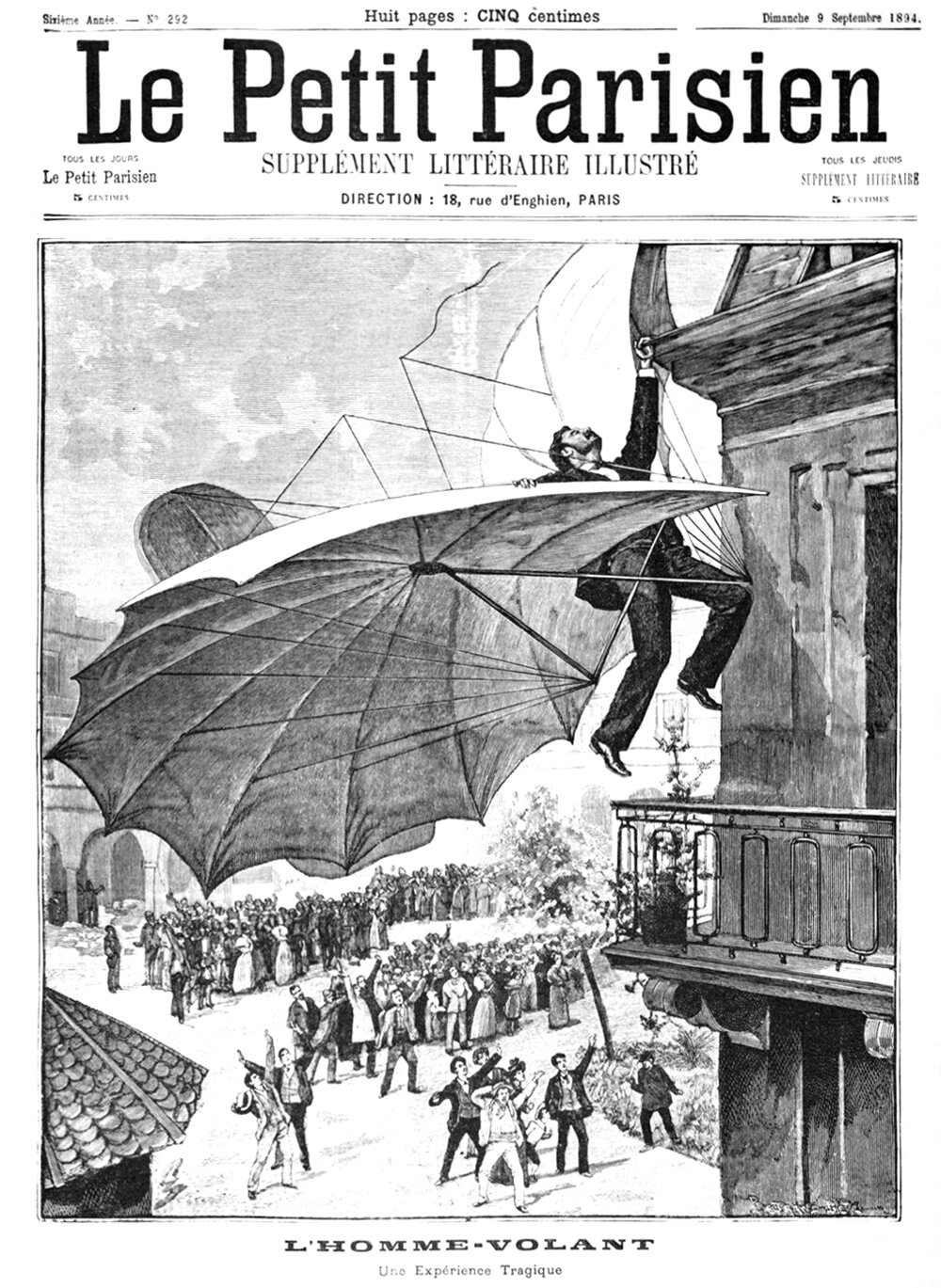

L’Homme Volant

Pictured above is the cover of Le Petit Parisien from 9 September 1894. It shows German aviation pioneer Otto Lilienthal dangling from a building cornice, with a crowd of onlookers below. According to the paper, the illustration was drawn from a photograph which was taken a few days earlier in Frankfurt, Germany.

Louis Charles Letur’s Parachute-Glider

Pictured above is an 1853 design for a flying machine by German engineer Louis Charles Letur. His design consisted of a pilot’s basket flanked by two triangular wings, along with a vertical tail behind (not pictured in the above illustration). This assembly would hang under a large umbrella-like parachute, and it was meant to be lifted to a height by some other means, such as a balloon, then it would glide safely back down to earth.

Earth, Air, Water and Fire : The Verticality of The Classical Elements

Throughout human history, our ancestors have created myriad different theories and ideas to explain our world and how it’s composed. One theory was common to nearly all early civilizations, and it identified four basic elements: earth, air, water and fire. If we examine these four elements and pick apart the relationships between them, we’ll find verticality at the center of it all.

“Go to, let us build us a city and a tower, whose top may reach unto heaven; and let us make us a name, lest we be scattered abroad upon the face of the whole earth.”

-The Book of Genesis, on the construction of the Tower of Babel.

Daedalus and Icarus : A Parable of Human Flight

The oldest and most storied myth of human flight is the Greek myth of Daedalus and Icarus. Any history of flight, if tracked back far enough, will find it’s inception rooted in this timeless tale of youthful hubris. Over the centuries, the name Icarus has become synonymous with over-ambition, and has inspired countless other stories relating to human flight.

Nicolas Edme Rétif’s Flying Man

The above illustration is from Nocolas Edme Rétif’s 1781 novel La Découverte Australe par un Homme-Volant, or The Discovery of the Austral Continent by a Flying Man. The fictional bird suit pictured was built by Victorin, the main character of the novel. He was in love with the daughter of a local lord, and he built a flying suit in order to kidnap her and fly her to the summit of a local mountain, where no people could reach.