Welcome to On Verticality. This blog explores the innate human need to escape the surface of the earth, and our struggles to do so throughout history. If you’re new here, a good place to start is the Theory of Verticality section or the Introduction to Verticality. If you want to receive updates on what’s new with the blog, you can use the Subscribe page to sign up. Thanks for visiting!

Click to filter posts by the three main subjects for the blog : Architecture, Flight and Mountains.

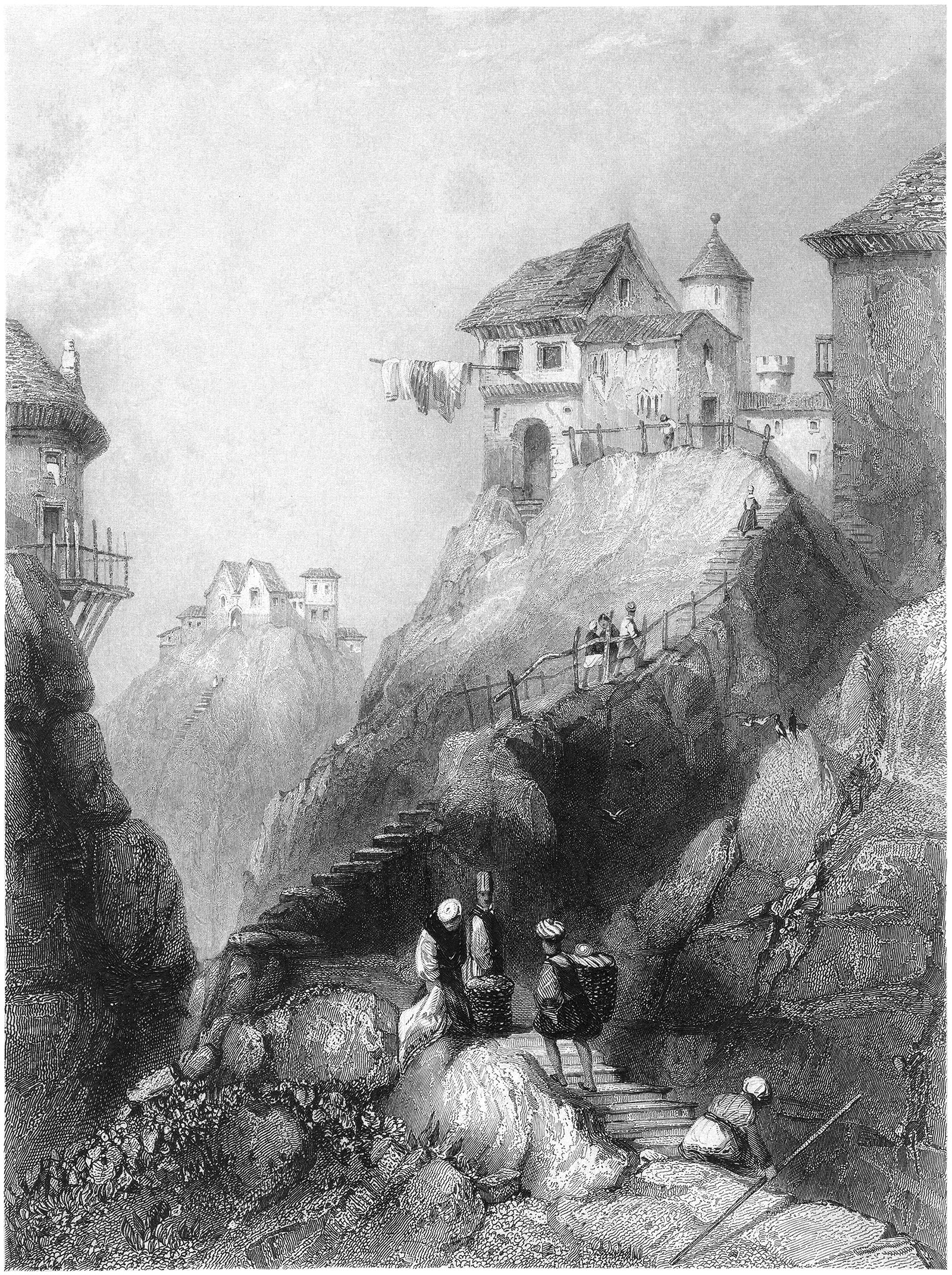

The Need to Build on High

There’s a need among humans to occupy and build on the highest places around. These places act like magnets for anyone living around them. There are many reasons for this, but they all boil down to verticality. Occupying or building on a high place means you’ve done battle with gravity, and you’ve won.

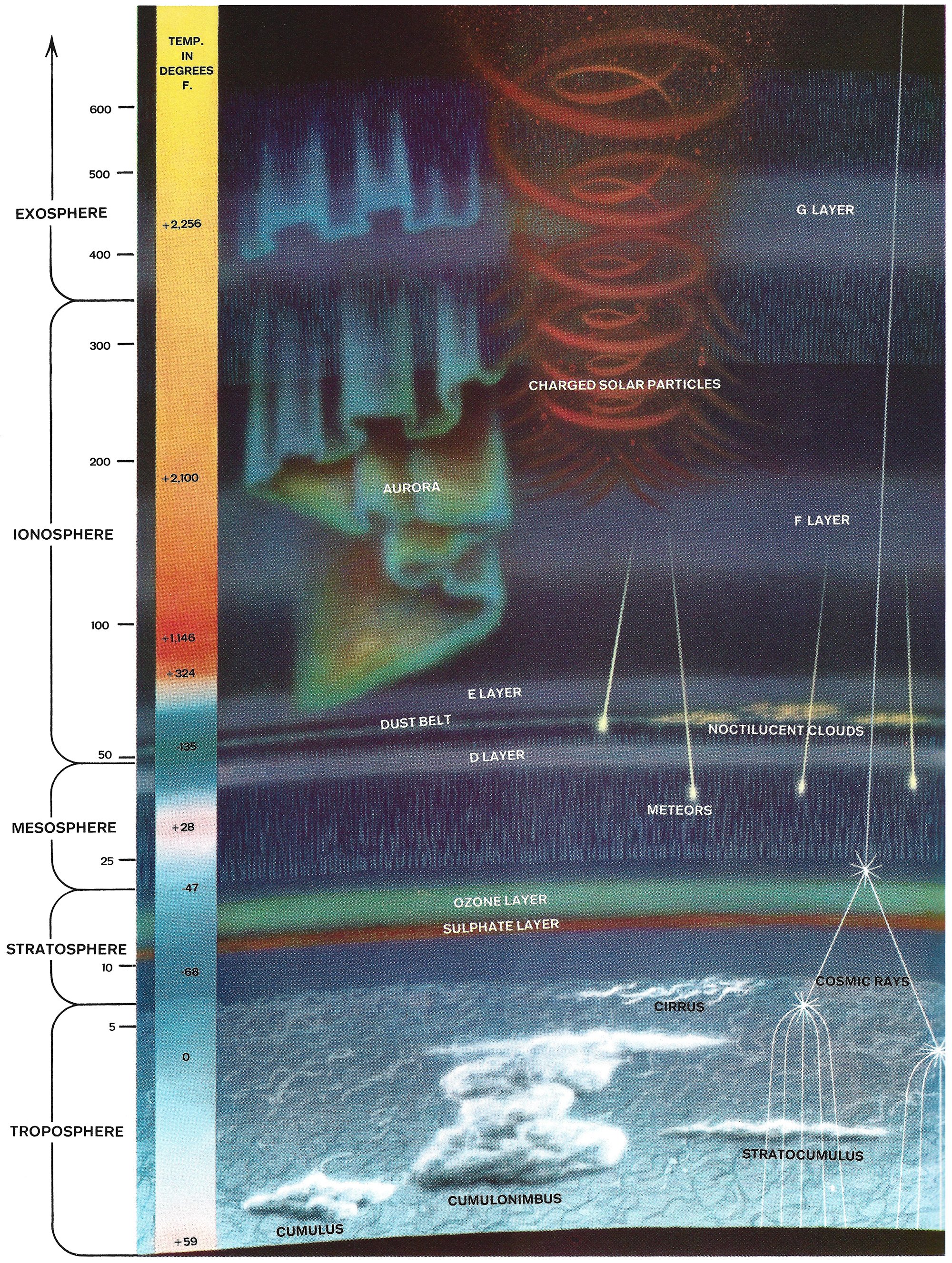

The Many-Layered Atmosphere

The above illustration originally appeared in the 1962 book The Earth from the Life Nature Library. It does a masterful job of explaining the complex layers of the earth’s atmosphere, and it puts the scale of each layer in perspective.

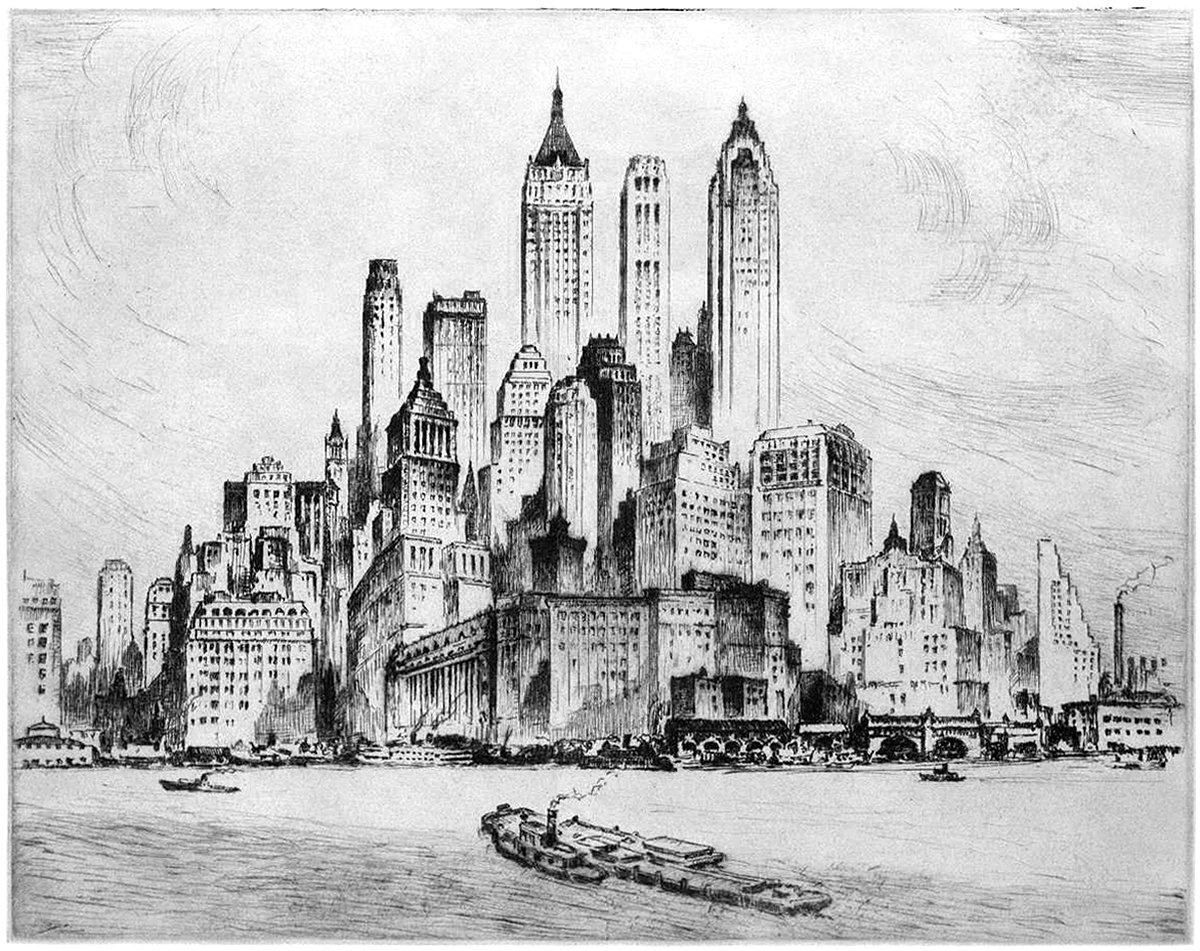

Nat Lowell and the Tip of Manhattan

Pictured here is an etching by artist Nat Lowell, showing the southern tip of Manhattan, circa 1940. The perspective is from the harbor, and Lowell focuses on three towers, which are the tallest of the bunch. From left to right, they include 40 Wall Street, 20 Exchange Place, and 70 Pine Street. The composition isn’t literal, and Lowell has taken some liberties to arrange the buildings into a mountain of sorts, with the three aforementioned towers at the summit.

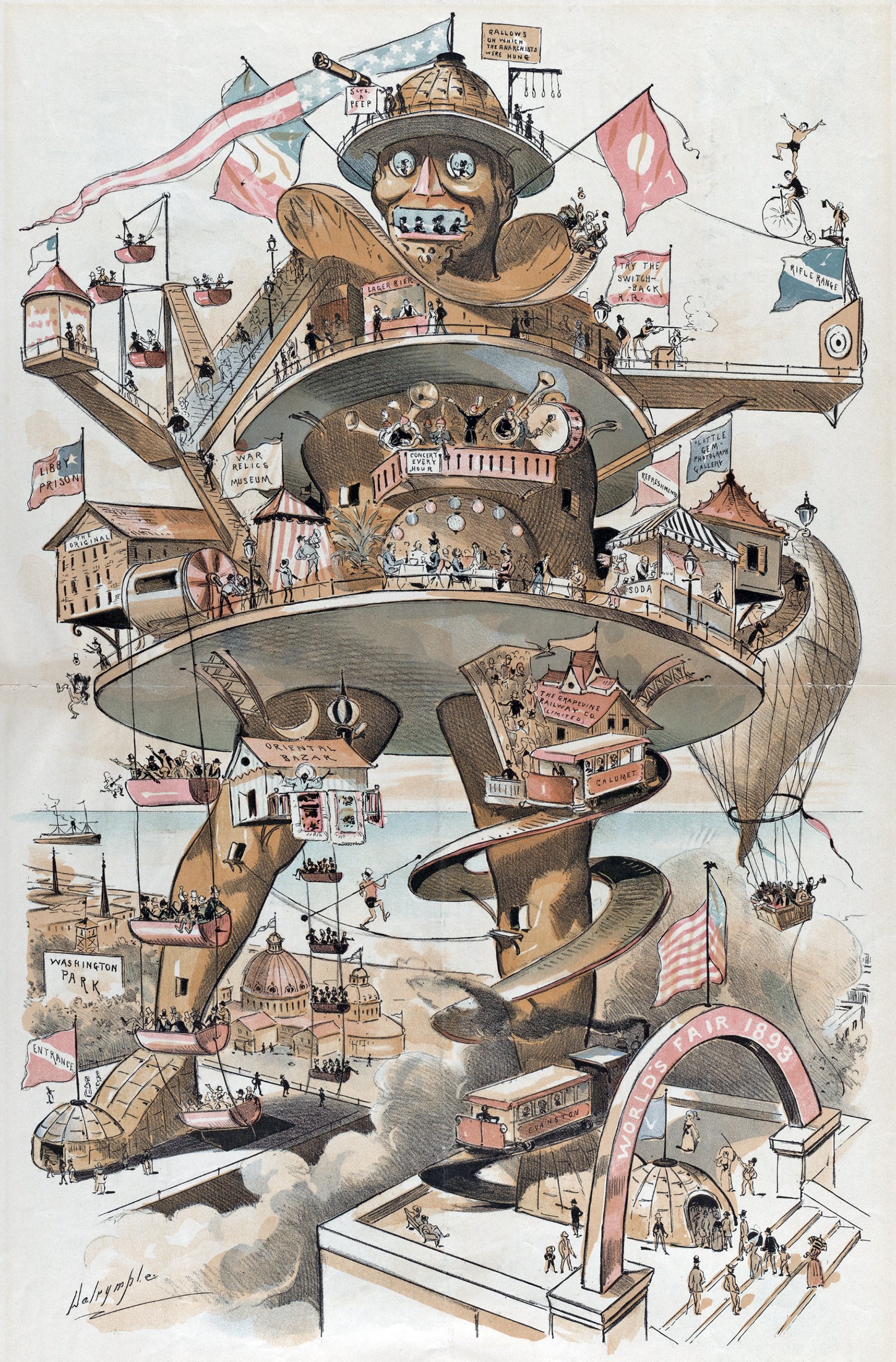

The Colossus of Chicago

The caption for the illustration shown above reads: Puck’s suggestion for the World’s Fair - the “Colossus of Chicago” would knock out the Eiffel Tower. It was drawn by Louis Dalrymple for the 8 October 1890 issue of Puck magazine, a popular humor and satire publication. With Colossus, Dalrymple was mocking a series of proposals leading up to the 1893 World’s Fair that sought to out-do the Eiffel Tower from the previous World’s Fair in Paris. Eiffel had become so popular that the organizers of the 1893 World’s Fair wanted to re-create its success in Chicago.

Madame Helene Alberti’s Cosmic Wings

Pictured here are two photographs from 1931 showing a winged glider designed by Madame Helene Alberti. Alberti was a well-known opera singer who studied human flight after retiring from the opera. She believed in the Ancient Greek laws of cosmic motion, and believed humans can fly by their own strength after learning to use these laws.

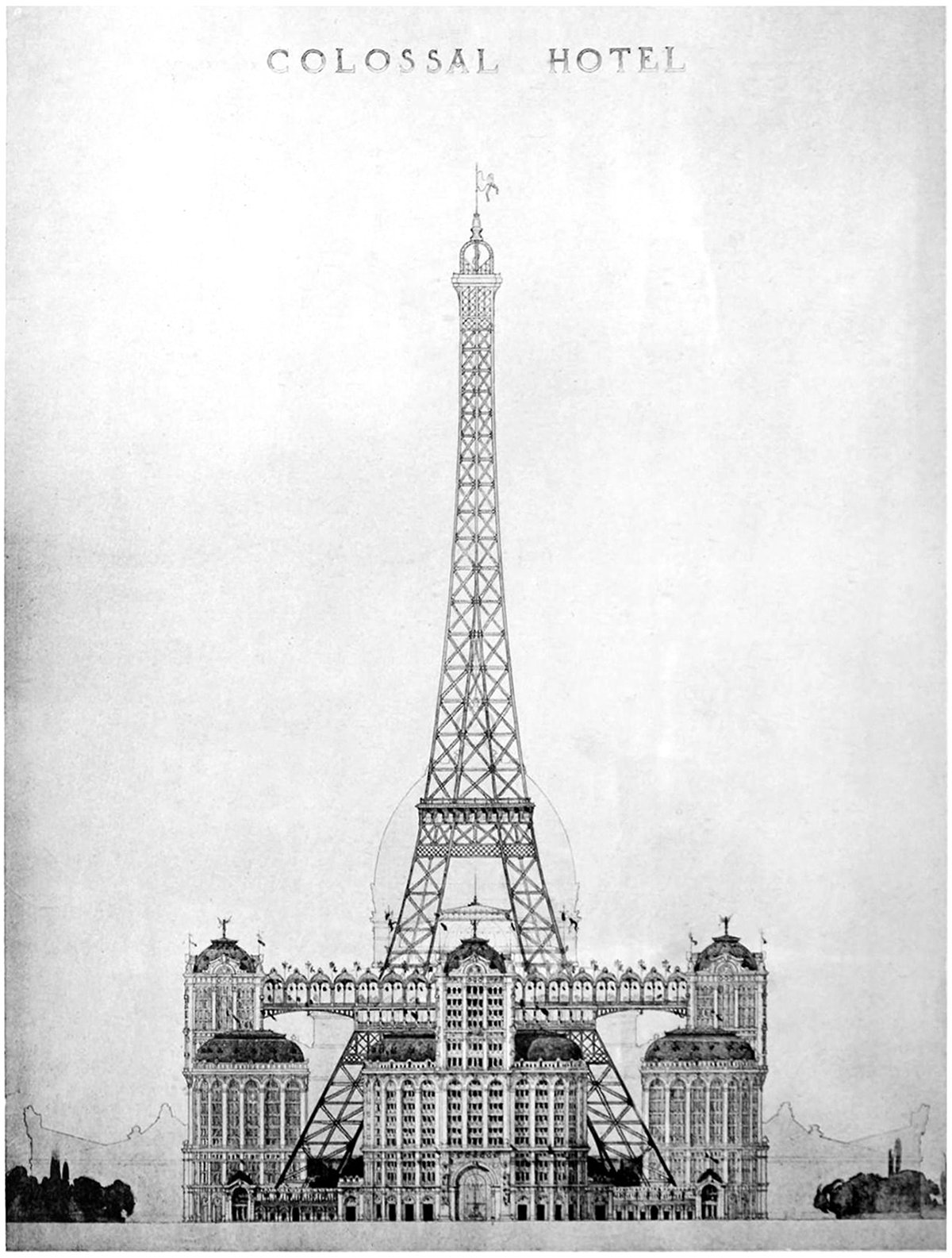

Alternate Realities : A Colossal Hotel at the Eiffel Tower

Pictured here is a proposal to put a colossal hotel at the base of the Eiffel Tower. It was proposed as part of the 1900 World’s Fair, called the Exposition Universelle, but it never got built. This elevation is the only drawing we have, which makes sense because most people who see the drawing would dismiss it immediately. The idea of filling up the void under the structure would destroy much of the Eiffel’s charm.

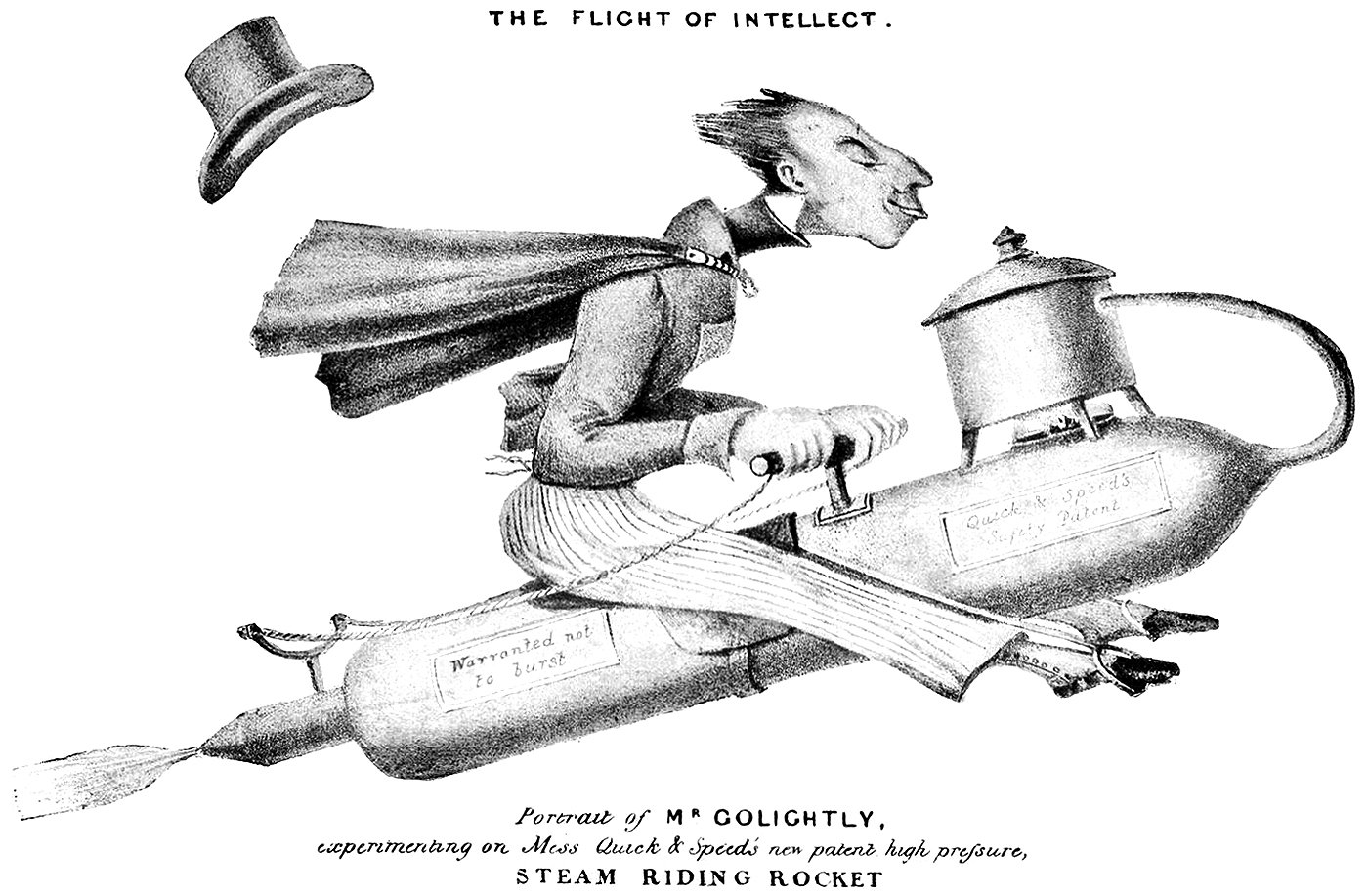

Mr. Golightly and the Flight of Intellect

Pictured here are a pair of cartoons drawn in the 1800s by Charles Tilt. They feature the character Mr. Golightly flying on a steam-powered rocket. The first, pictured above, is from 1826 and it features a well-dressed Mr. Golightly sitting on his rocket, flying fast through the air. The caption reads Portrait of Mr. Golightly, experimenting on Mess Quick & Speed’s new patent high pressure, steam riding rocket.

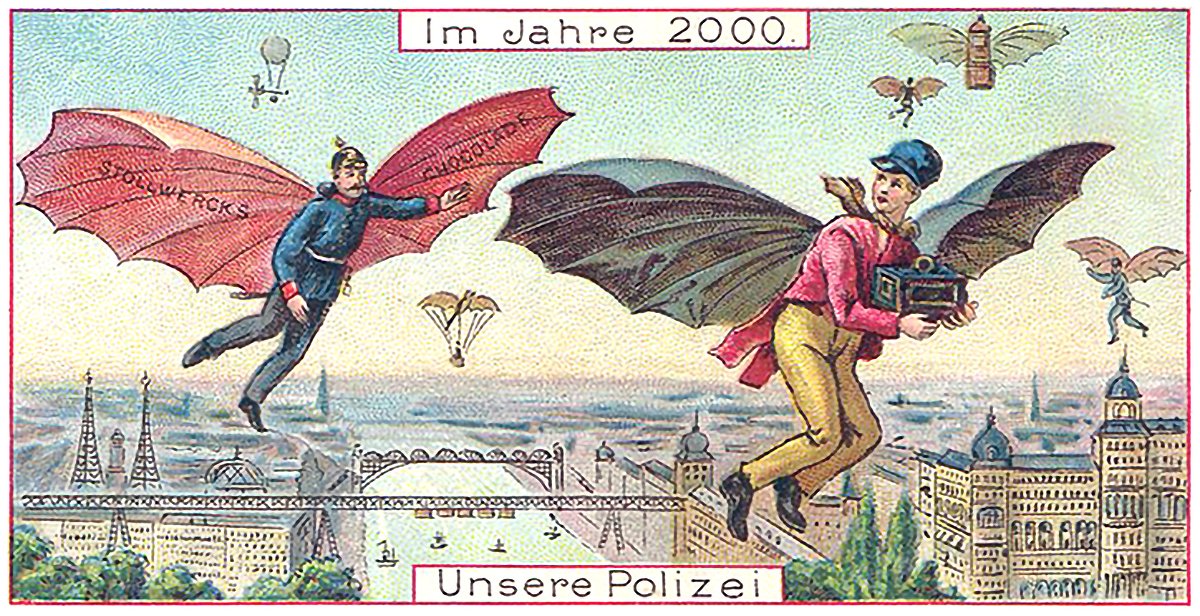

Im Jahre 2000 : In the Year 2000

The early twentieth century was a time of optimism towards the future. Aeronautics and flight were on the public’s consciousness, and there was much speculation about how the future would look once humanity conquered the skies. Pictured here is one such vision. It’s from a set of six cards titled Im Jahre 2000, which is German for In the Year 2000. What’s interesting about the set is that three of the cards deal with flight.

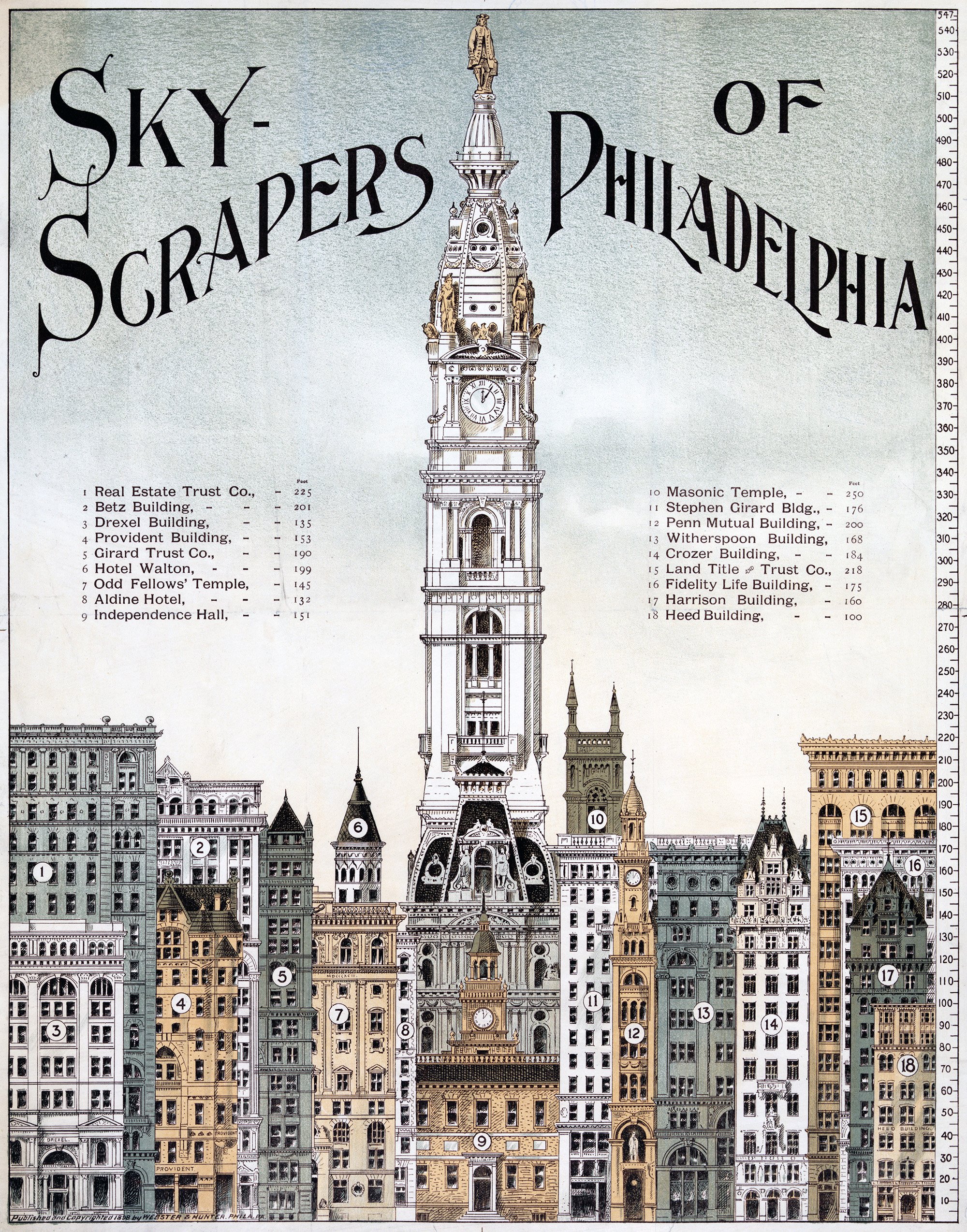

Skyscrapers of Philadelphia

The illustration above shows a lineup of tall buildings from 1898 in Philadelphia. All of them are of similar height, save for the City Hall Clock Tower. It stands alone, rising to a height of 548 feet, or 167 meters. It was the tallest building in the world when it was completed in 1894, and remained so until the completion of the Singer Building in New York in 1908. This status as the world’s tallest building is reinforced by the illustration, which shows it utterly dominating the other buildings in the city.

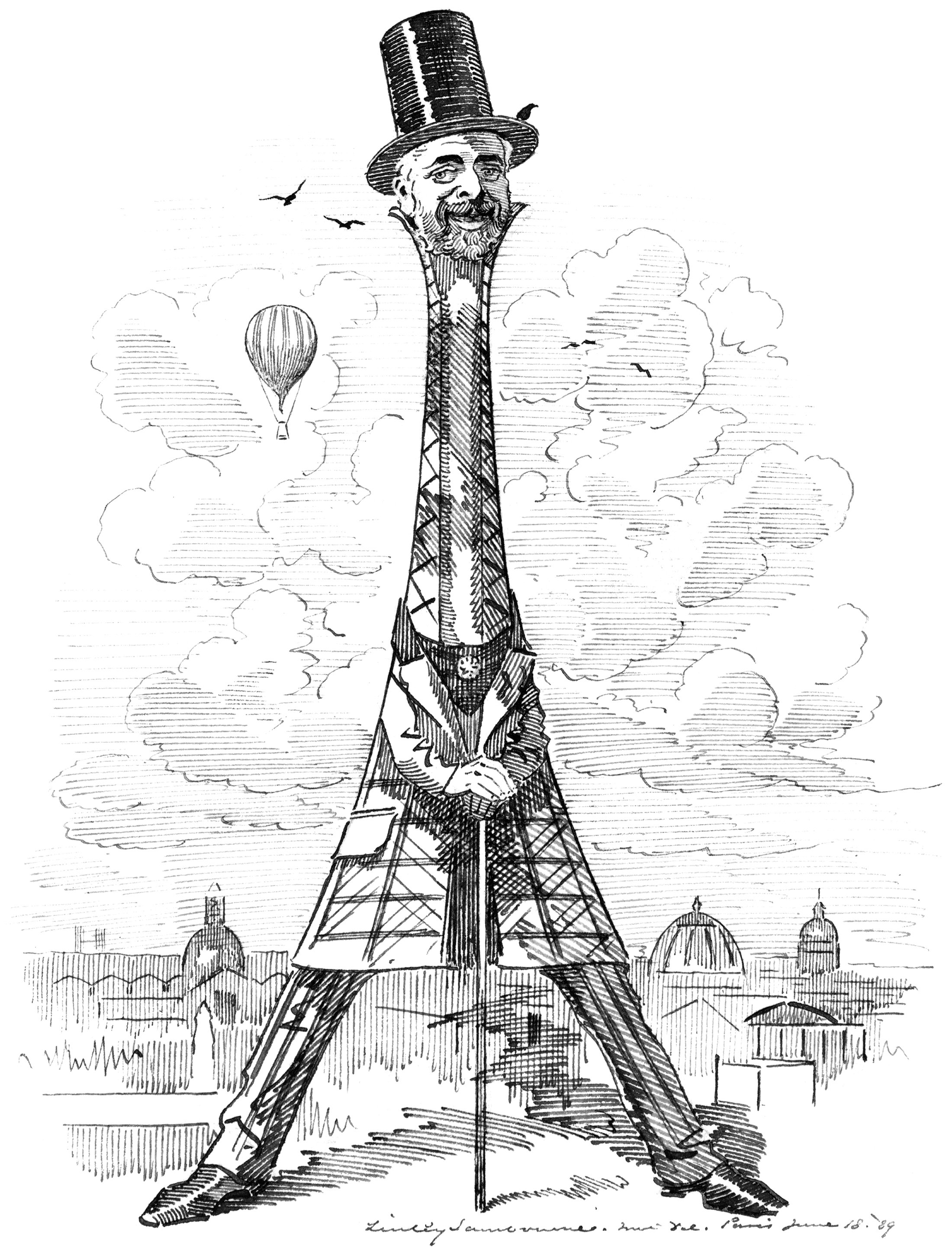

Eiffel as his Tower

Our buildings reflect our values and needs. This is especially true of our tall buildings, because they cost so much to build. When the Eiffel Tower was built in Paris, it reflected a worldwide drive for height in our buildings that was emerging at the time. It was a such a powerful statement of verticality that the man who designed it became something of a celebrity. He became linked with the tower in the eyes of the public, so much so that it was named after him like one of his children. This rarely happens with a building, but it demonstrates just how big an impact the Eiffel Tower had on the world.

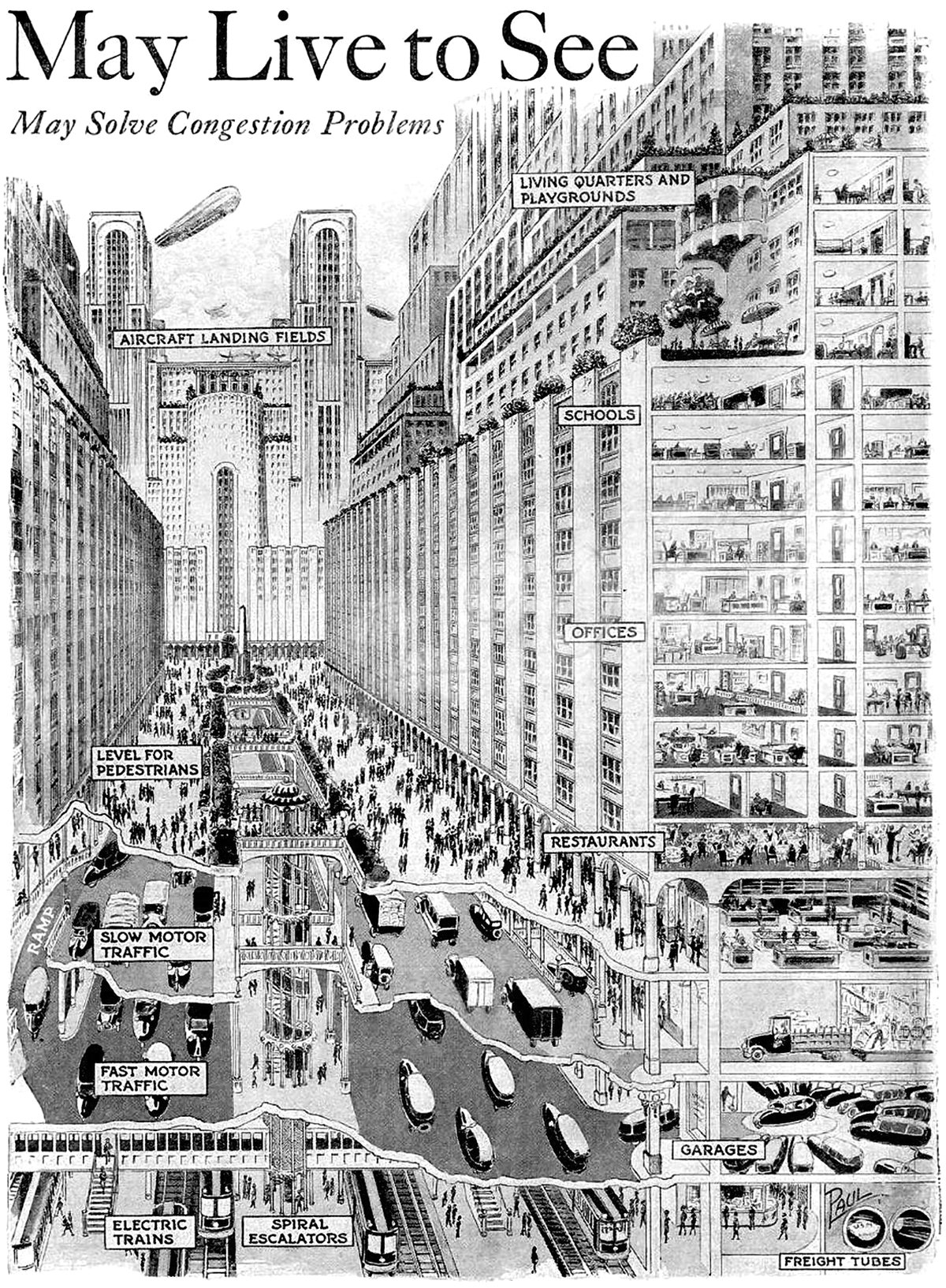

How You May Live and Travel in the City of 1950

Pictured above is a vision for a future city from 1925, which predicted what cities would look like in 1950. It’s quite an ambitious proposal, since it required sweeping urban changes to occur in only 25 years. The changes feature a vertical separation of city functions that start below the ground and end on top of skyscrapers.

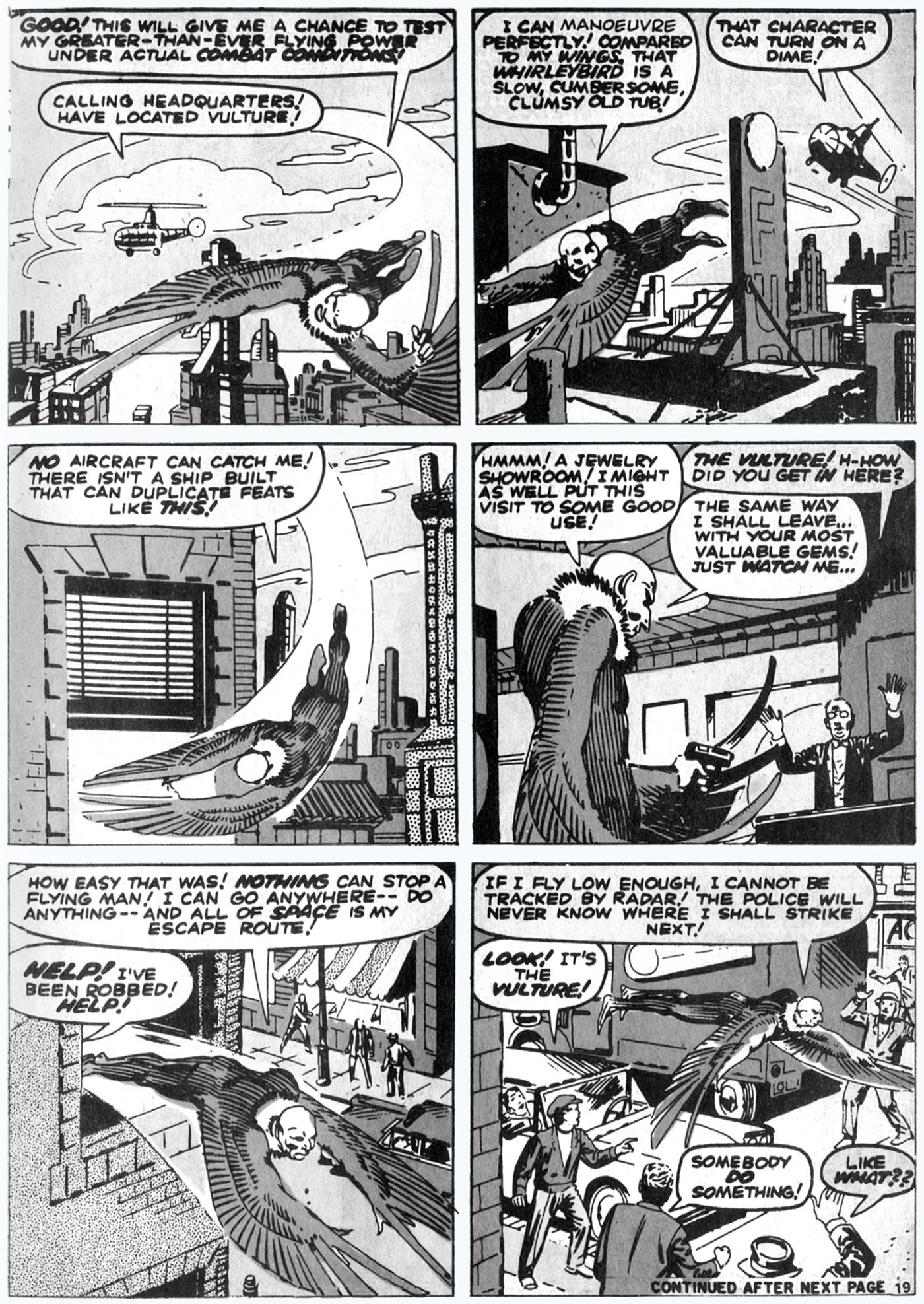

Nothing can stop a flying man!

In many ways, comic books function as folk tales for modern society. They tell stories of the eternal conflict of good and evil, with super-human characters who can do things common people can’t. Of these abilities, the most common is flight. The ability to fly is something every person understands, and it gives any character an immediate and excessive advantage over anyone who can’t. Pictured above is a page from a Spider-Man comic from 1973, showing the villain testing out his newly-acquired flying power.

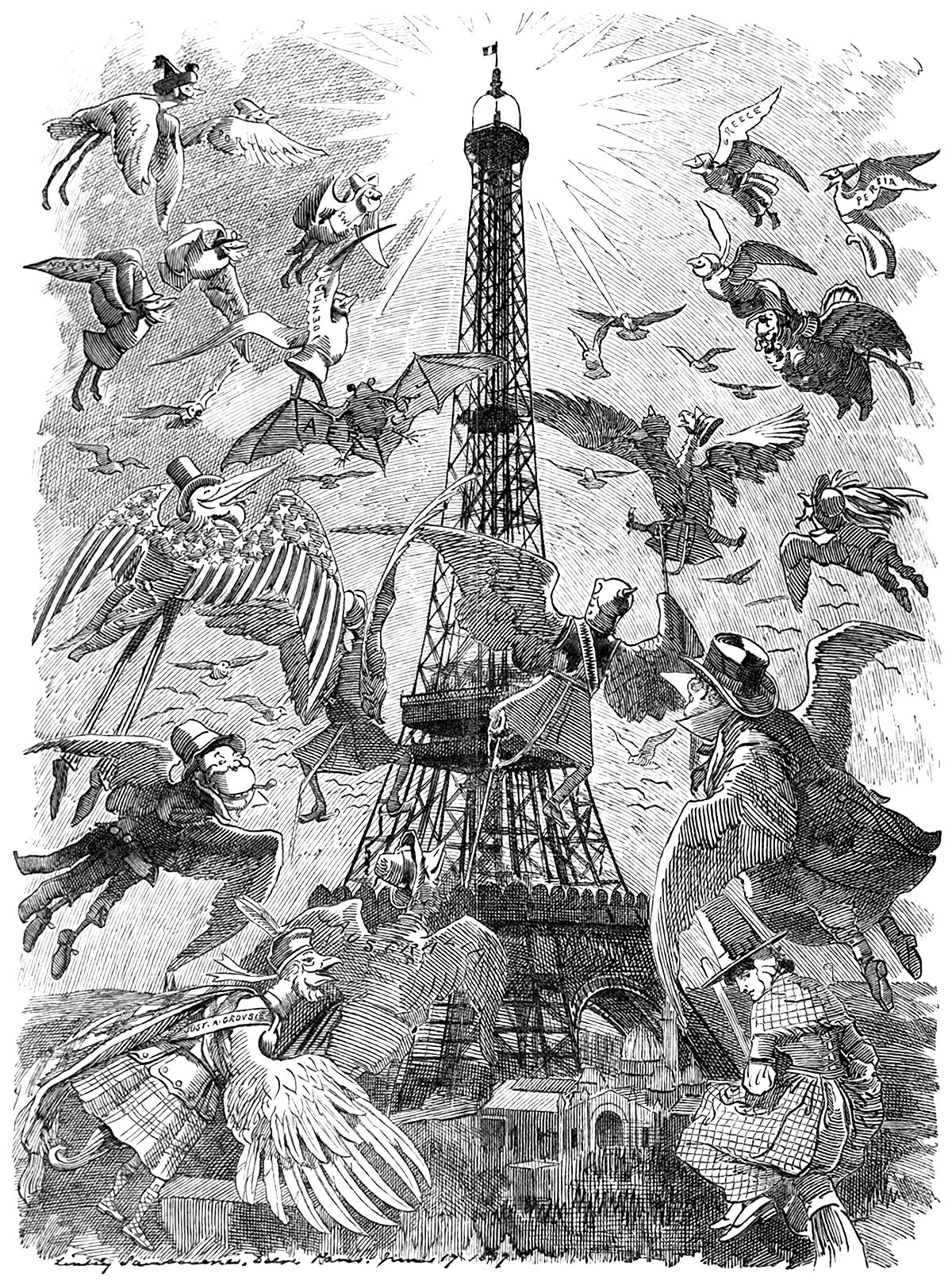

The Eiffel Tower Effect

When the Eiffel Tower was completed in 1889 for the World’s Fair in Paris, it changed the world. It re-defined what humans were capable of, and it gave the city of Paris an architectural icon that hasn’t faded with age. It was the tallest structure in the world, and it allowed its visitors to achieve verticality. As such, upon its completion the world took notice. Countless media sources reported on the structure, and it instantly took its place on the world stage. Pictured above is one such example of this. It’s an illustration from an 1889 issue of Punch magazine, and it shows a flock of birds flying toward the Eiffel Tower. These birds represent the countries of the world, and the piece was meant to symbolize the world’s envy for the iconic tower.

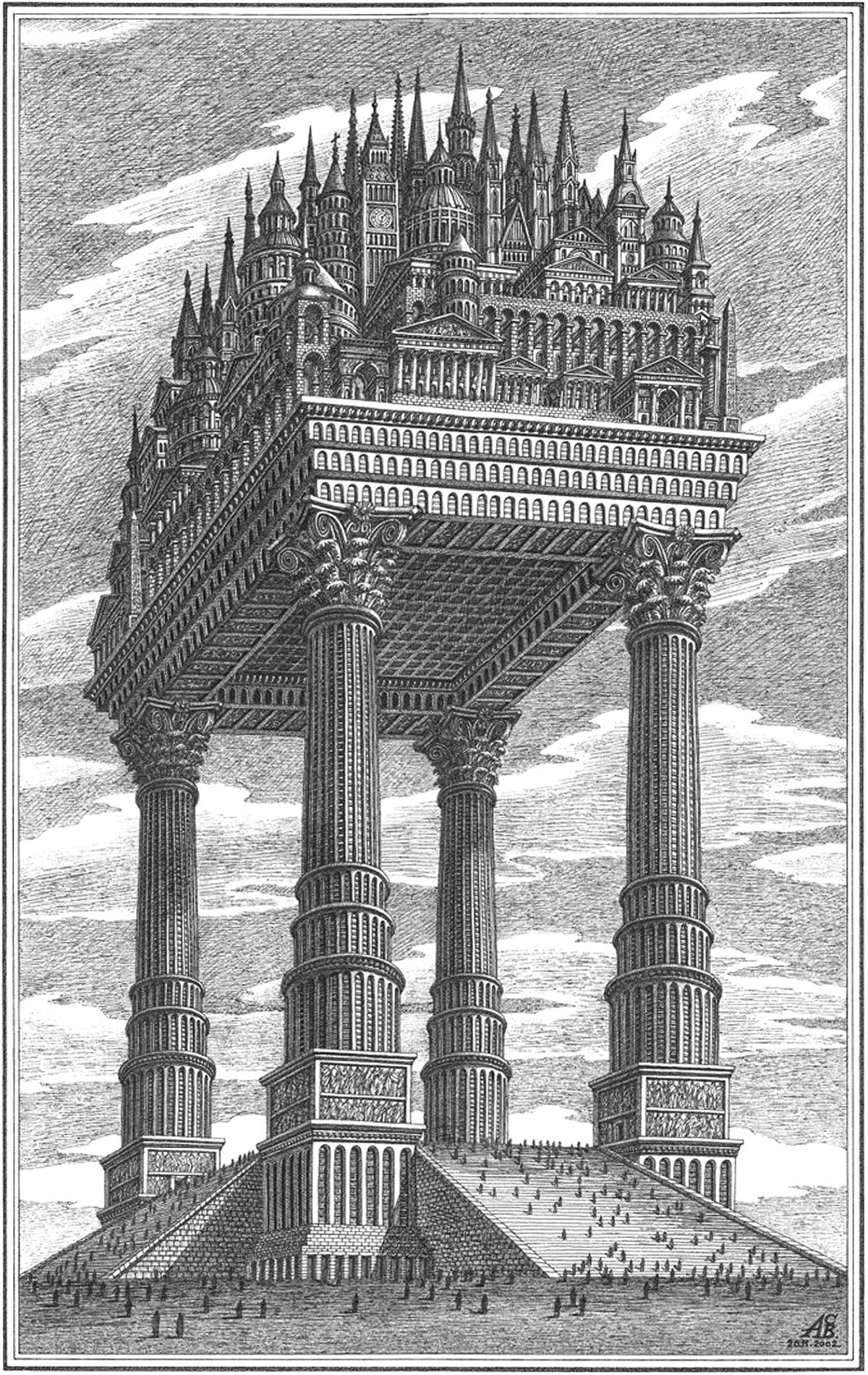

The Magic City

Pictured above is an illustration by Russian architectural theorist Arthur Skizhali-Weiss. It’s part of a series called The Magic City, which includes fictional realities dreamed up by the architect from 1999 to 2014. Apart from being an interesting composition of architectural forms, it embodies a few themes related to verticality.

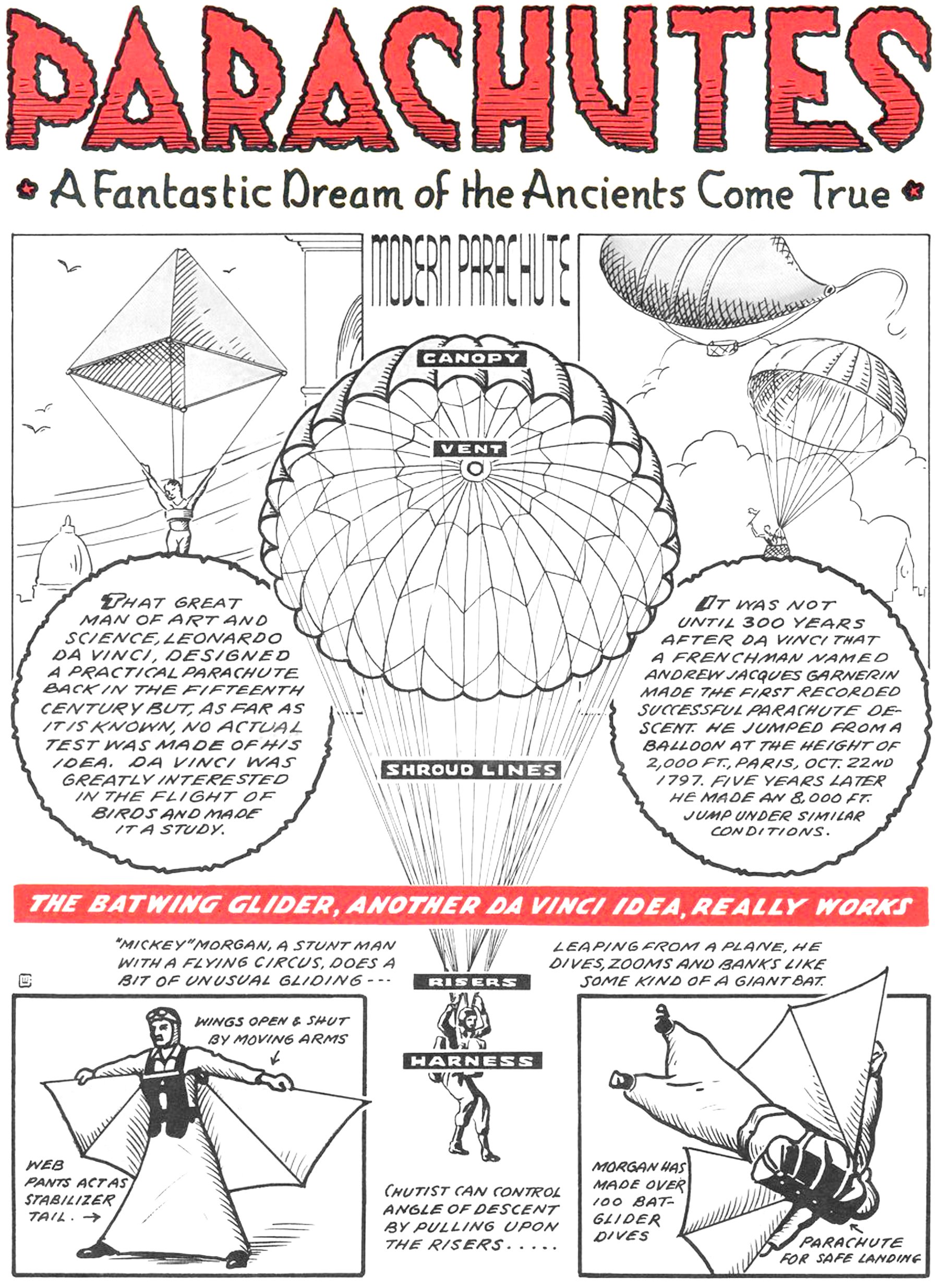

Parachutes : A Fantastic Dream of the Ancients Come True

Pictured above is a page from a War Heroes comic book from 1943. It features a few examples of parachutes and a flying suit called the Batwing Glider. At the center of the page is a modern parachute, complete with its canopy, vent, shroud lines, risers and harness. Flanking this drawing are two historical examples of parachutes. The first is a sketch from Leonardo da Vinci’s notebooks circa 1495, and the second is the world’s first successful parachute descent by André-Jacques Garnerin in 1797. This triad presents a concise, albeit incomplete history of parachute design, but it does do a good job of visually connecting a modern parachute to its ancestors.

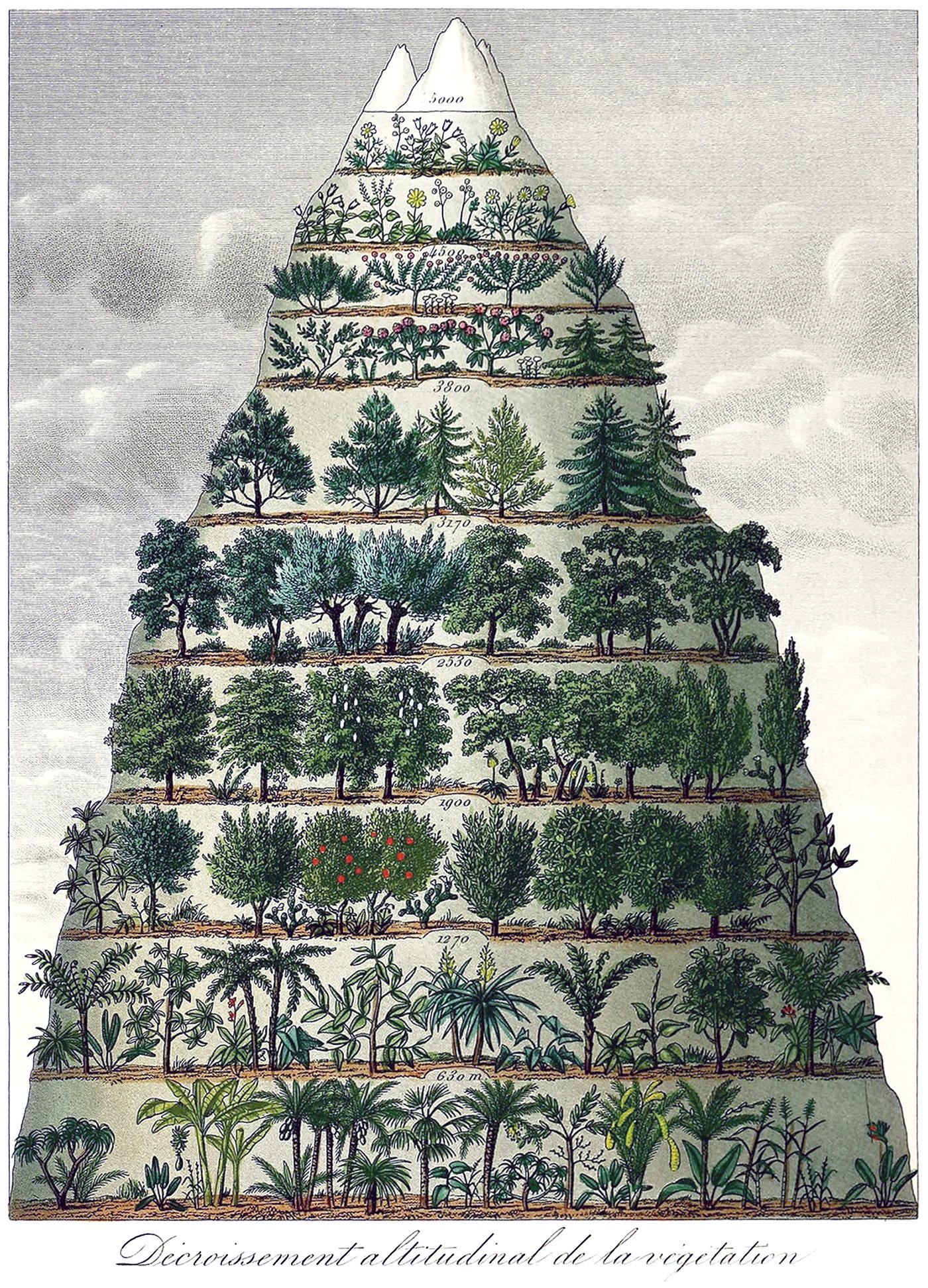

The Altitudinal Decrease in Vegetation

Pictured above is an illustration from the 1860s by Jean-Augustin Barral, titled Décroissement Altitudinal de la Végétation, which is French for The Altitudinal Decrease in Vegetation. It’s a beautiful work that attempts to categorize vegetation types by elevation, which is known as altitudinal zonation. Barral gets the overall concept correct, but we now know the details to be much more nuanced and complex than his drawing suggests.

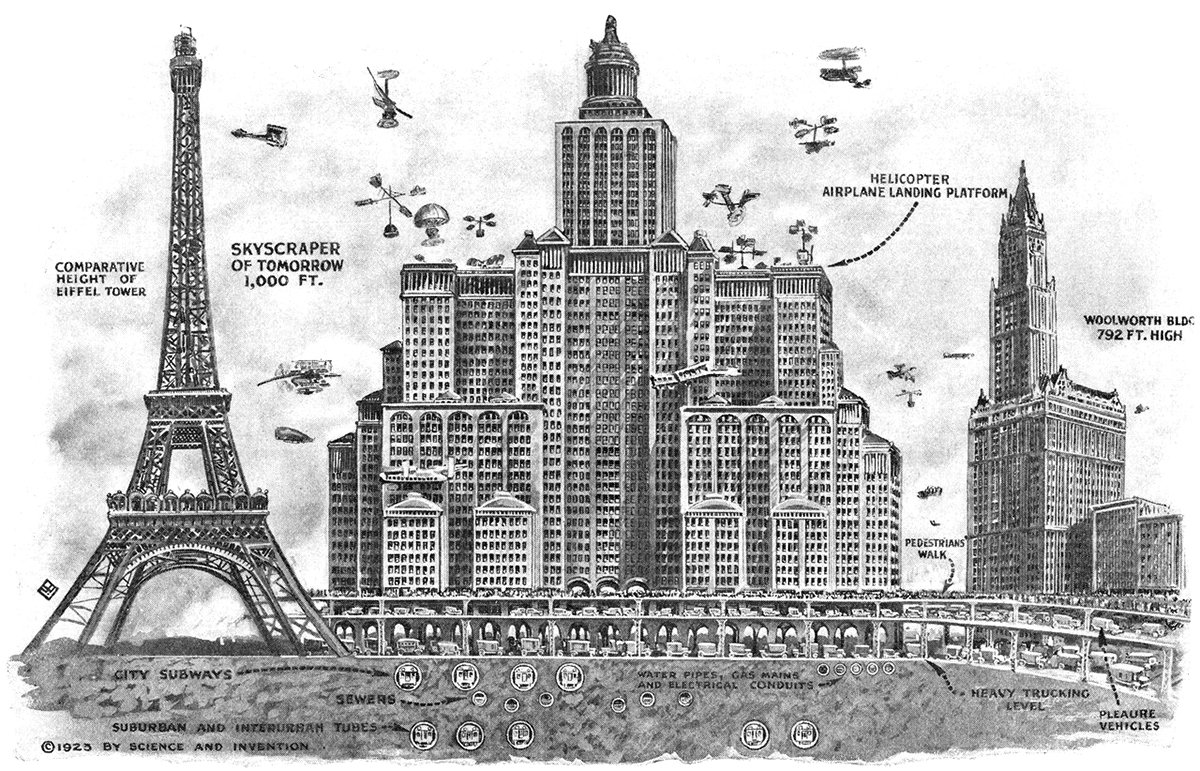

Skyscrapers of To-morrow

Pictured above is a 1923 illustration showing Harvey Wiley Corbett’s idea for a future skyscraper. Corbett believed buildings would continue to get taller and wider, resulting in massive, slab-like structures with aircraft landing platforms on their roofs and multiple underground levels of traffic. He compares his concept with two iconic buildings of the time, the Eiffel Tower and the Woolworth Building. These were both the tallest in the world when completed, which really hits home the sheer scale of Corbett’s structure.

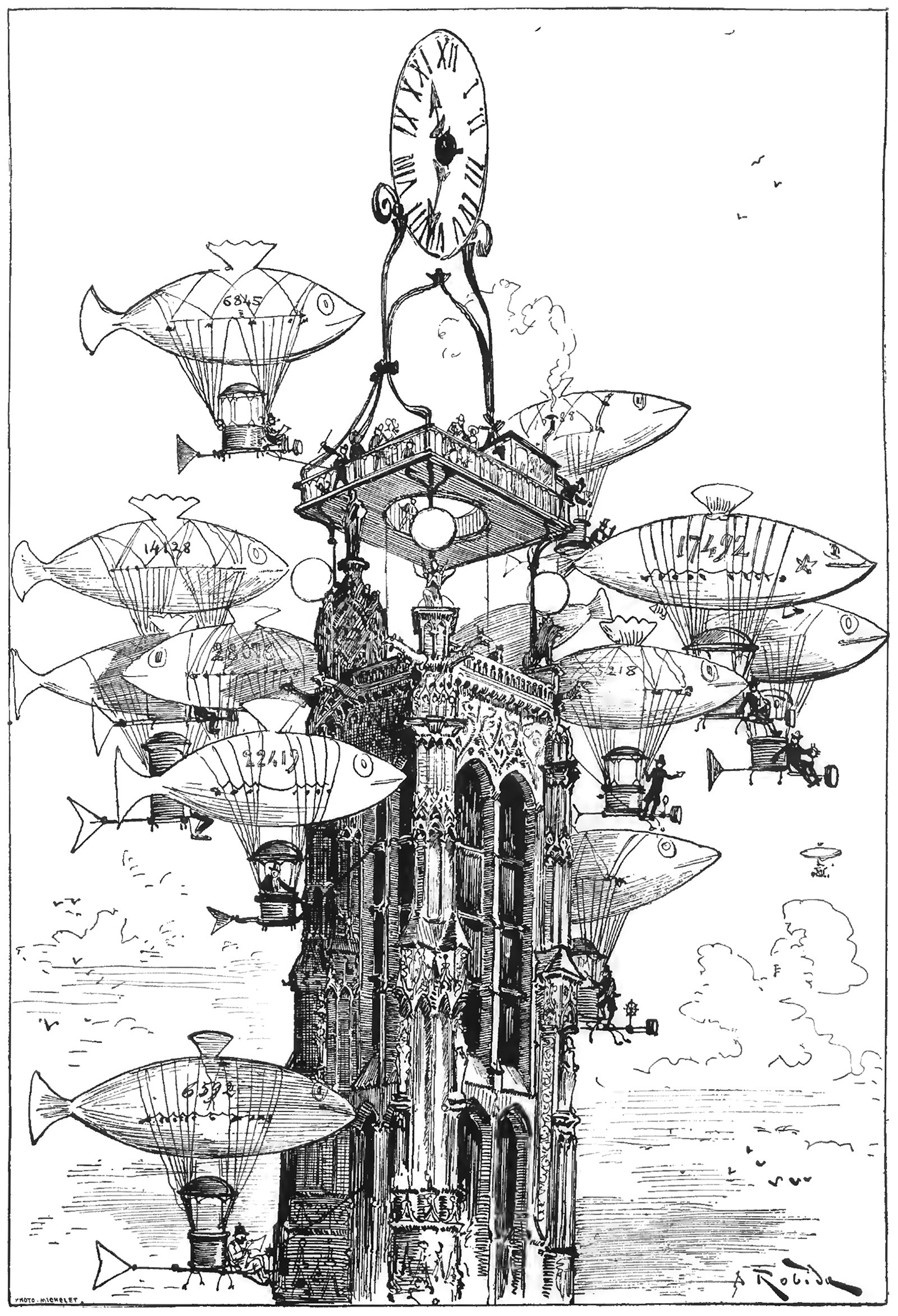

An Aerocab Station atop the Tour Saint-Jacques

The above illustration was drawn by Albert Robida for his 1883 novel Le Vingtième Siècle, or The Twentieth Century. This illustration was titled La Station d'Aerocabs de la Tour Saint-Jacques, or The Aerocab Station of the Tour Saint-Jacques, and it shows a raised platform and clock atop the iconic Parisian structure. Flocking around the tower is a group of dirigibles made to look like fish. What’s charming about the image is how the cluster of dirigibles resemble a school of fish, almost crowding out the tower itself from the image.

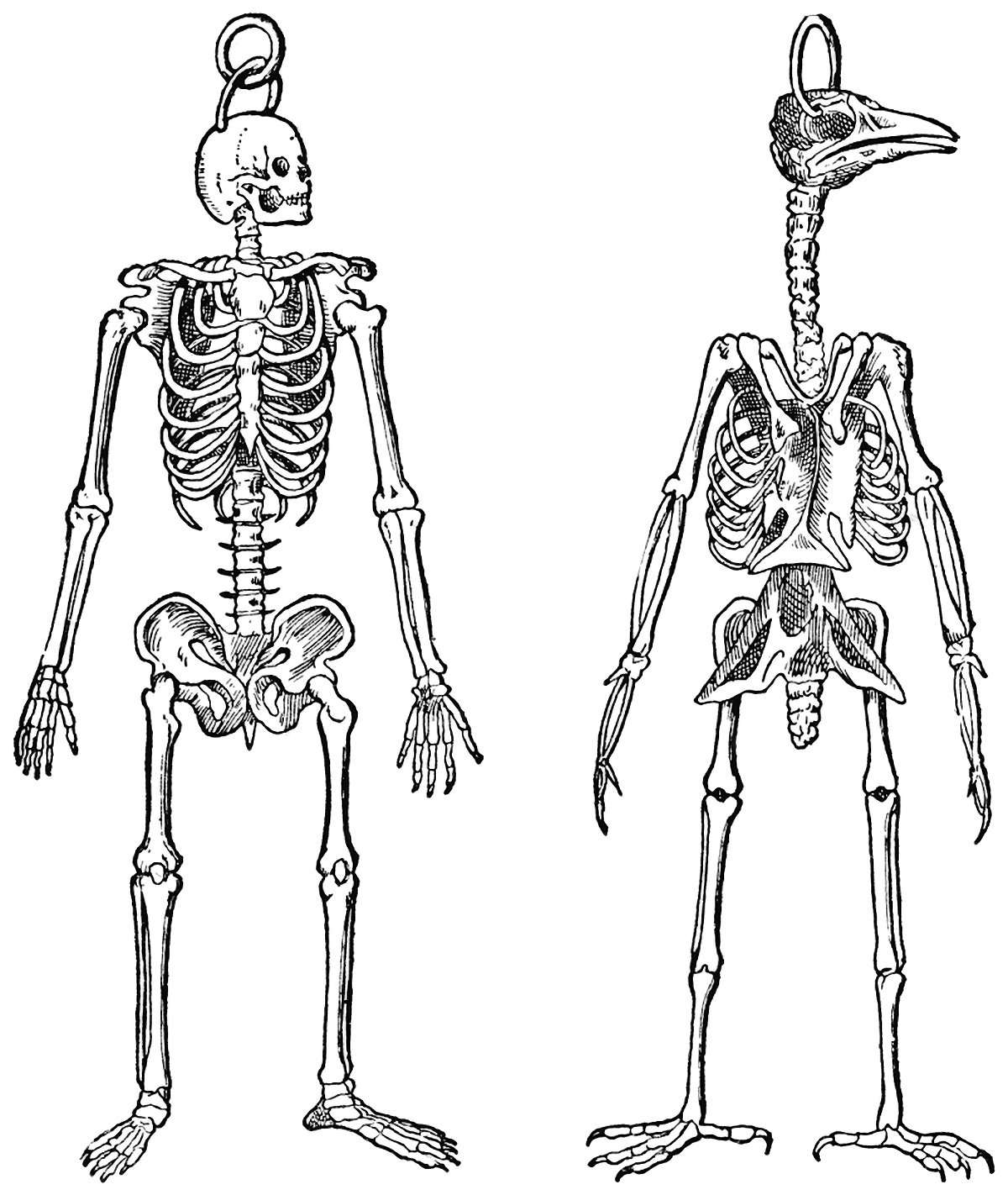

The Skeletons of a Man and Bird

Pictured above is a comparison between the skeleton of a human and a bird. What I find fascinating about this image is the choice of the artist to position the bird in a bipedal stance. I suspect this was done just to ease the comparison, but in a way it undermines the birds power of flight. This is an animal who is at home when in the open air, but here the bird is shown with its feet firmly planted on the ground, much like a human. The playing field has been leveled, so to speak, which puts the bird at a specific disadvantage.

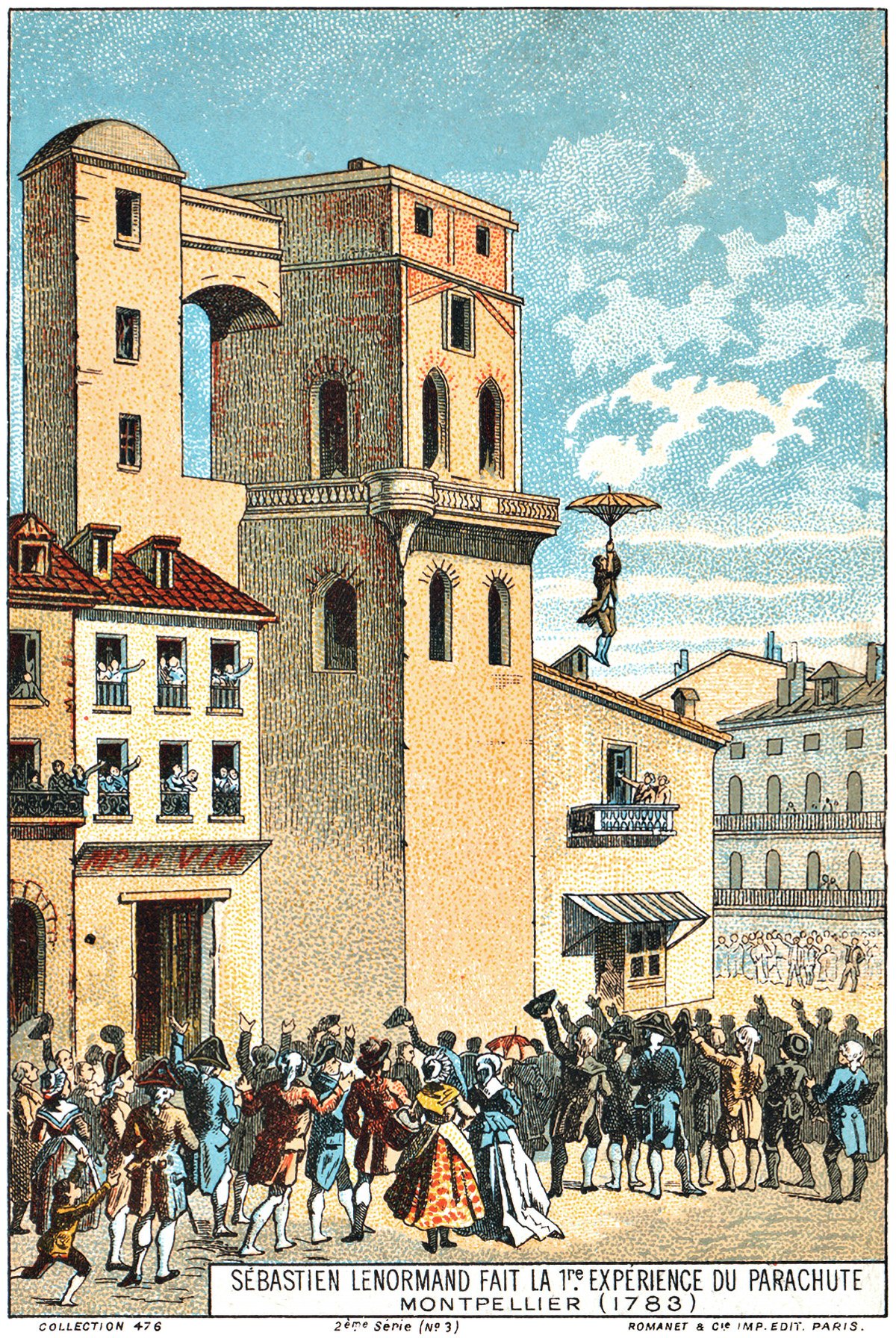

Sébastien Lenormand’s First Parachuting Attempt

Pictured above is a French illustration from 1890, showing Louis-Sébastien Lenormand leaping from a building with his parachute in Montpellier, France in 1783. He jumped from the Montpellier Observatory in front of a large crowd of onlookers who were hoping to witness the first-ever successful parachute demonstration. The caption reads Sébastien Lenormand Fait la 1re Expérience du Parachute, which means Sébastien Lenormand’s First Parachuting Attempt.