How to Fall : An Early History of the Parachute

A pair of sketches, originally published in an anonymous manuscript from Italy in the 1470s, showing two early ideas for parachutes. On the left is a design consisting of two large ribbons of fabric, attached to the pilots waist. On the right is a design consisting of a conical parachute with a cross frame, also attached to the pilot’s waist.

Throughout the history of human flight, the number one cause of death and injury has been a fall from a high place. In the early days of flight attempts, most examples involved starting from a high perch, such as a tower or a hilltop. An individual would then throw themselves into the air, hoping their design would catch the air and allow them to fly. If this didn’t work, they would fall down to the surface, resulting in injury or death. It was a terribly dangerous endeavor, but it’s a testament to the human need for verticality that so many individuals continued to try it. Alongside these attempts at flight, others were concerned with the art of falling. How could a person leap from a high place and return to the surface safely? The resulting paths of thought make up the early history of the parachute.

The oldest documented parachute design we have is the pair of sketches pictured above. They were drawn by an unknown author in Italy, sometime around the 1470s. The first shows a man with a pair of large cloth strips attached to his waist and controlled by two bars that he grasps in his hands. Somehow, these strips of fabric were meant to slow down a fall. In his mouth is a sponge, which was meant to protect his jawbone from the shock of a fall.[1] The second sketch also includes a sponge, but this time it’s attached to his mouth by a strap. This design features a conical parachute with two crossing bars attached to the ring at the base. The man grabs these bars with his hands and hangs below the cone, while the ends of each bar are attached to his waist by ropes. It’s a simple design, and in many ways it forms the basis for the parachutes we still use today. It’s much too small to function, however, and wouldn’t succeed in slowing him down enough to prevent injury.

A sketch by Leonardo da Vinci, circa 1485, from his Codex Atlanticus showing a rough design for a parachute.

The next documentation we have comes from a few years later, by Italian polymath Leonardo da Vinci. We don’t know if da Vinci was aware of the previous sketches, so we cannot say for sure if he was influenced by them. His sketch, which is less detailed but more sophisticated, was drawn around 1485, which puts it only a few years after the first example. It consists of a pyramidal parachute with a central, vertical rod that extends below its base. The bottom of this rod is attached to the four corners of the base, while a man hangs below, holding on with both his hands. The size of da Vinci’s parachute is bigger than the previous sketch, but still seems too small to carry a person’s full body weight.

These first two examples use rigid frames and taught surfaces for their parachute. As a result, they seem to be fighting the fluid nature of the air, and their inherent inflexibility gives them an unstable feeling. To illustrate this point, think of a ship’s sail. Much like a modern parachute, a sail is meant to catch a mass of air and control movement in some way. Unlike these first two designs, however, a ship’s sail is flexible, which allows it to catch a larger mass of air, increasing it’s effectiveness. Apply this concept to the parachute, and you get a more effective design. This brings us to the third example, pictured below. It was designed around 1615 by another Italian polymath, Fausto Veranzio.

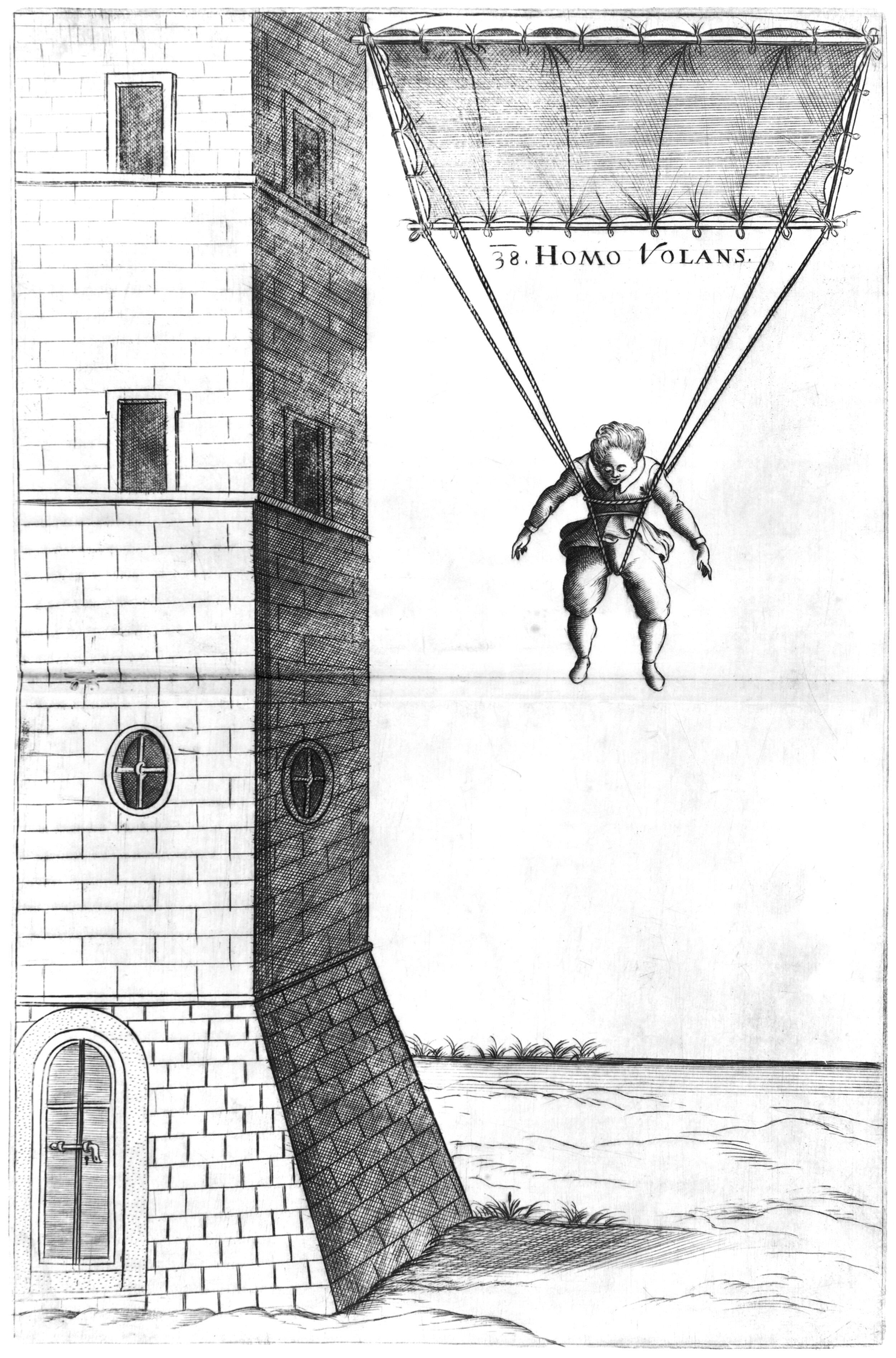

Illustration from Machinae Novae, written around 1615 by Fausto Veranzio. The work included mechanical and technical innovations and inventions, including this design for a parachute, titled Homo Volans, or Flying Man.

Veranzio took da Vinci’s square frame, made it bigger and attached a sail-like piece of fabric to it. His design, which was published in his 1615 work Machinae Novae, shows a man jumping from a medieval tower. The man, called Homo Volans, or Flying Man, hangs below the parachute with a simple harness made of ropes. This parachute, which is bigger than da Vinci’s, seems much more believable in scale. It also begins to resemble modern parachutes, with it’s bulging fabric form that cradles a large mass of air. There’s also a growing distance between human and parachute. In previous examples the man was right at the base of the parachute. Here, the man’s body is a good distance from the base and the entire design appears much more stable as a result.

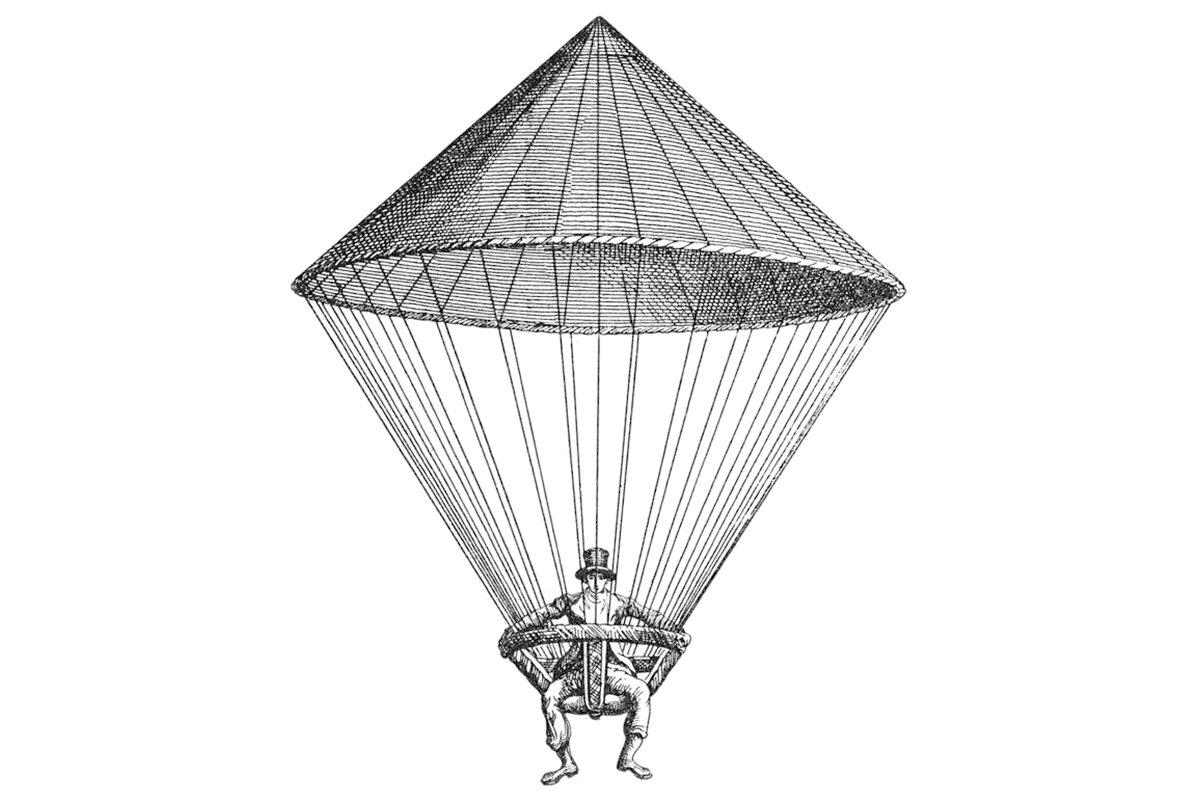

Up to this point, all we have are sketches or concepts. We don’t have evidence that any of them were built or tested in the real world, so we can only speculate on how far these studies went. It wasn’t until 1783 that the first successful public demonstration of a parachute was made. The designer was Louis-Sébastien Lenormand, and his parachute is shown below. It’s quite a bit more developed than any of the previous examples, most likely because Lenormand was actually building and testing prototypes along the way. At first glance, the main features are a 14-foot conical parachute connected to a simple basket by an array of ropes. The basket is left largely open, and a man sits in it with his legs hanging out, dangling in the air below. The design’s first public demonstration was on 28 December 1783. Lenormand jumped from the Montpellier Observatory in France and landed safely on the ground, to the astonishment of a crowd of onlookers. This is credited as the world’s first successful public demonstration of a parachute. It was the same year the Montgolfier Brothers were making their ground-breaking balloon flights, and it’s believed that Joseph Montgolfier witnessed one of Lenormand’s public demonstrations.

Illustration of Louis-Sébastien Lenormand’s 1783 design of a parachute. He is credited with the first-ever witnessed descent when he jumped from the Montpellier Observatory on 28 December 1783 and landed unharmed.

Aside from the world’s first successful parachute demonstration, Lenormand also coined the term parachute, which combines the Latin prefix para, which means against, with the French word chute, which means fall. Thus, the word parachute means against a fall.

After Lenormand made his successful public demonstrations, focus turned to frameless designs, which were lighter and could pack down much smaller than a rigid frame could. In 1797, French balloonist André-Jacques Garnerin developed a frameless parachute made of silk. His design is pictured below, consisting of a basket at the base, a parachute in the middle, and a balloon at the top. Garnerin performed the world’s first descent of a frameless parachute with this design on 22 October 1797 in Paris. The balloon was filled and the craft was released, causing it to ascend into the air. Once the proper altitude was reached, Garnerin released the balloon, causing the basket to fall and the parachute to open. Once it fully opened it caught the air and slowed the craft’s descent, allowing it to safely return to the ground.

Illustration of André-Jacques Garnerin’s frameless parachute design. The design was made of silk, and it made the world’s first frameless parachute descent on 22 October 1797 in Paris.

Garnerin’s frameless parachute would become the standard for subsequent parachute design, and many similarities can be found between it and modern parachutes in use today. Many refinements have been made over the years, of course, but the basic concept is there. Today, a person can wear a backpack that contains a full-size parachute which can be deployed at will. No more rigid frames to worry about. Modern parachutes are used all over the world, both for pleasure and for safety during myriad different activities. One could even say that humans have not only perfected the ability to fly, but also the ability to fall.

Check out other posts about flight and flying machines here.

[1]: White, Lynn. "The Invention of the Parachute." Technology and Culture 9, no. 3 (1968): 462-67.