Welcome to On Verticality. This blog explores the innate human need to escape the surface of the earth, and our struggles to do so throughout history. If you’re new here, a good place to start is the Theory of Verticality section or the Introduction to Verticality. If you want to receive updates on what’s new with the blog, you can use the Subscribe page to sign up. Thanks for visiting!

Click to filter posts by the three main subjects for the blog : Architecture, Flight and Mountains.

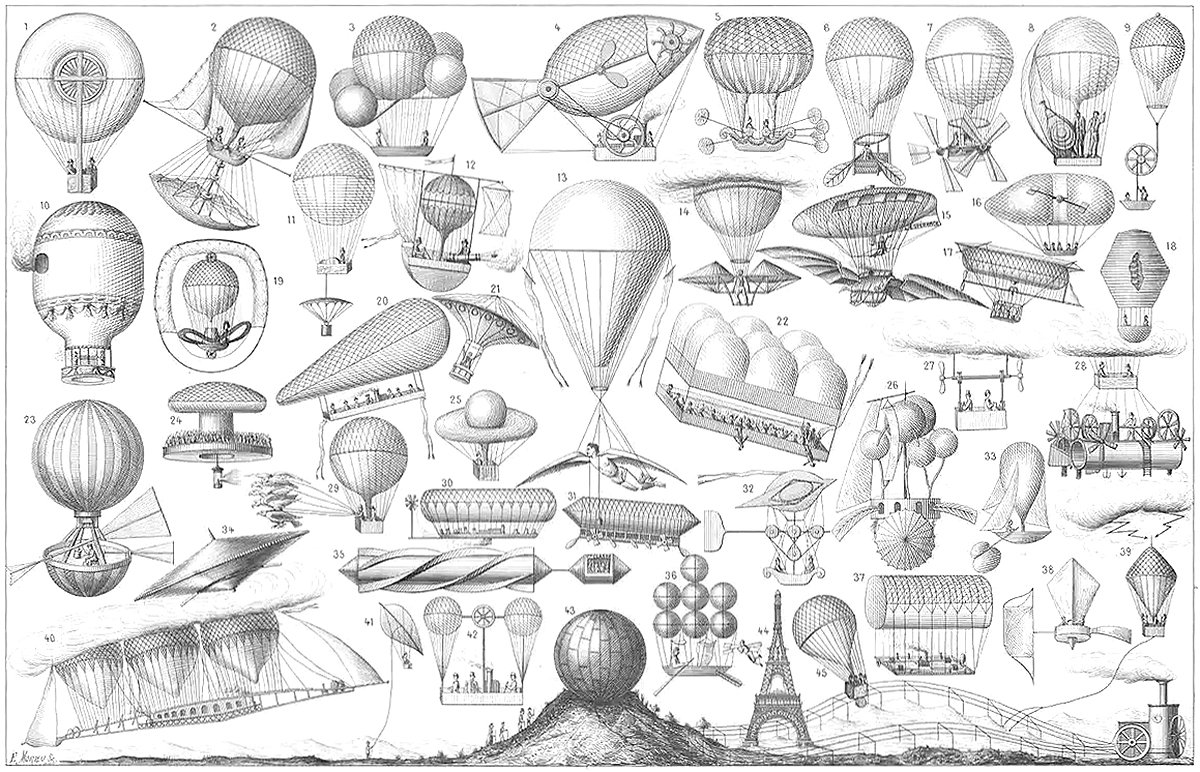

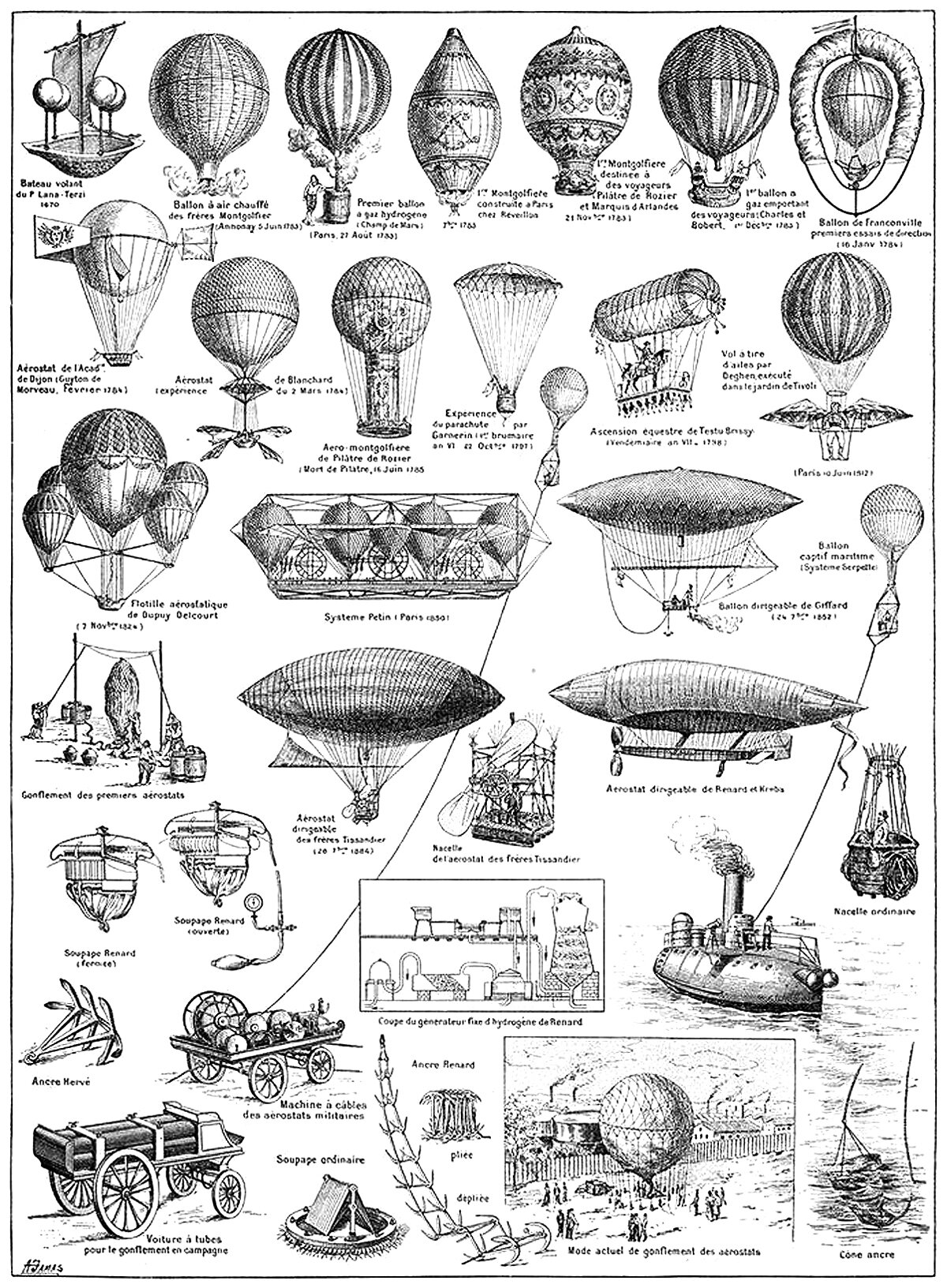

A Compendium of Dirigibles

Pictured above is an exhaustive collage of early dirigible designs, circa 1885 by E. Morieu. As far as I can tell, there’s forty-five designs in total, and many of them seem quite unique. Most likely the original print was paired with a descriptive list, but unfortunately this link has since been broken. Even so, there’s great beauty in the variety of the designs shown here, as well as the creative spirit that led to all of them. A collage like this is evidence of the human need for verticality, that all these individuals would put so much time and effort into achieving human flight.

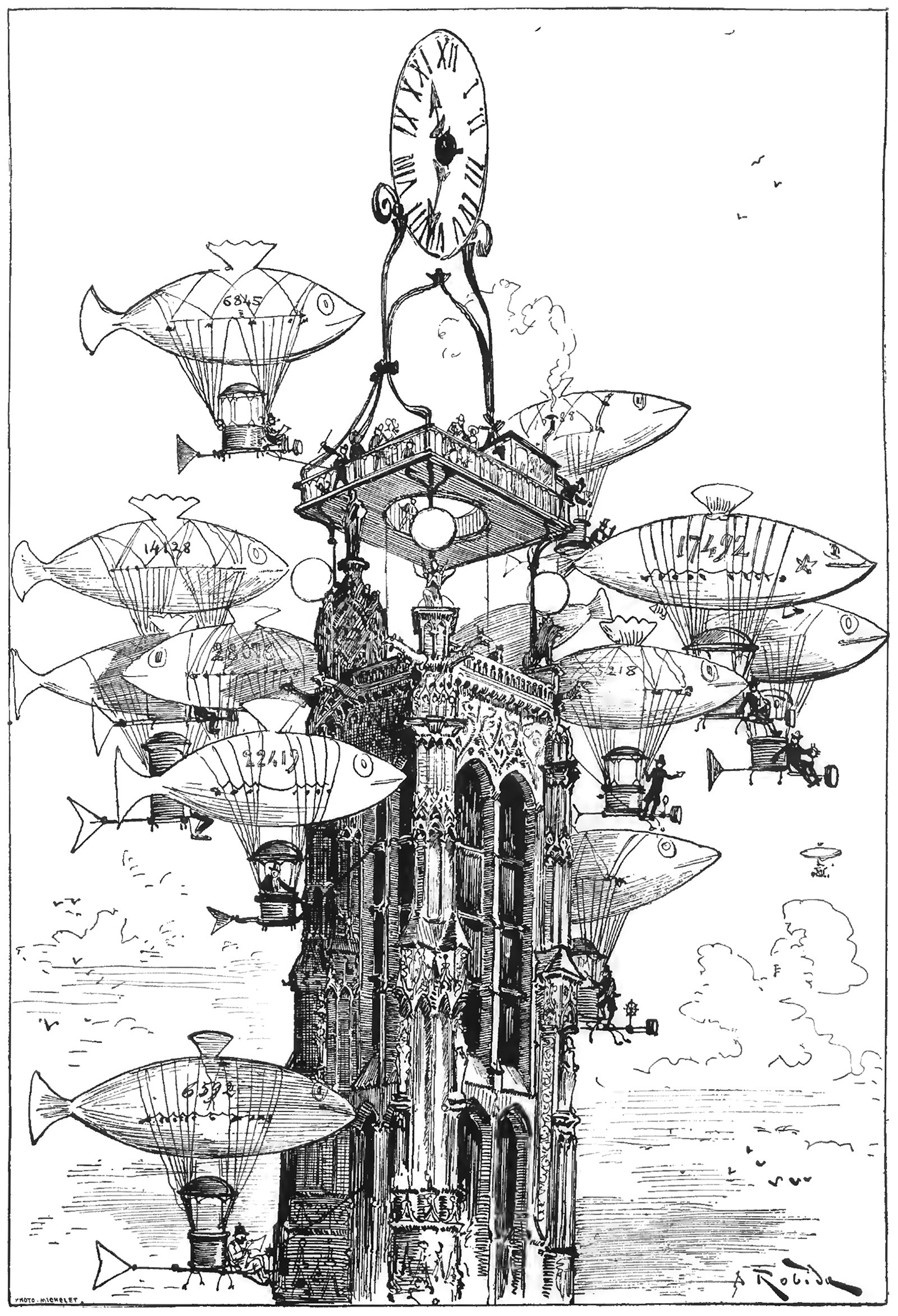

An Aerocab Station atop the Tour Saint-Jacques

The above illustration was drawn by Albert Robida for his 1883 novel Le Vingtième Siècle, or The Twentieth Century. This illustration was titled La Station d'Aerocabs de la Tour Saint-Jacques, or The Aerocab Station of the Tour Saint-Jacques, and it shows a raised platform and clock atop the iconic Parisian structure. Flocking around the tower is a group of dirigibles made to look like fish. What’s charming about the image is how the cluster of dirigibles resemble a school of fish, almost crowding out the tower itself from the image.

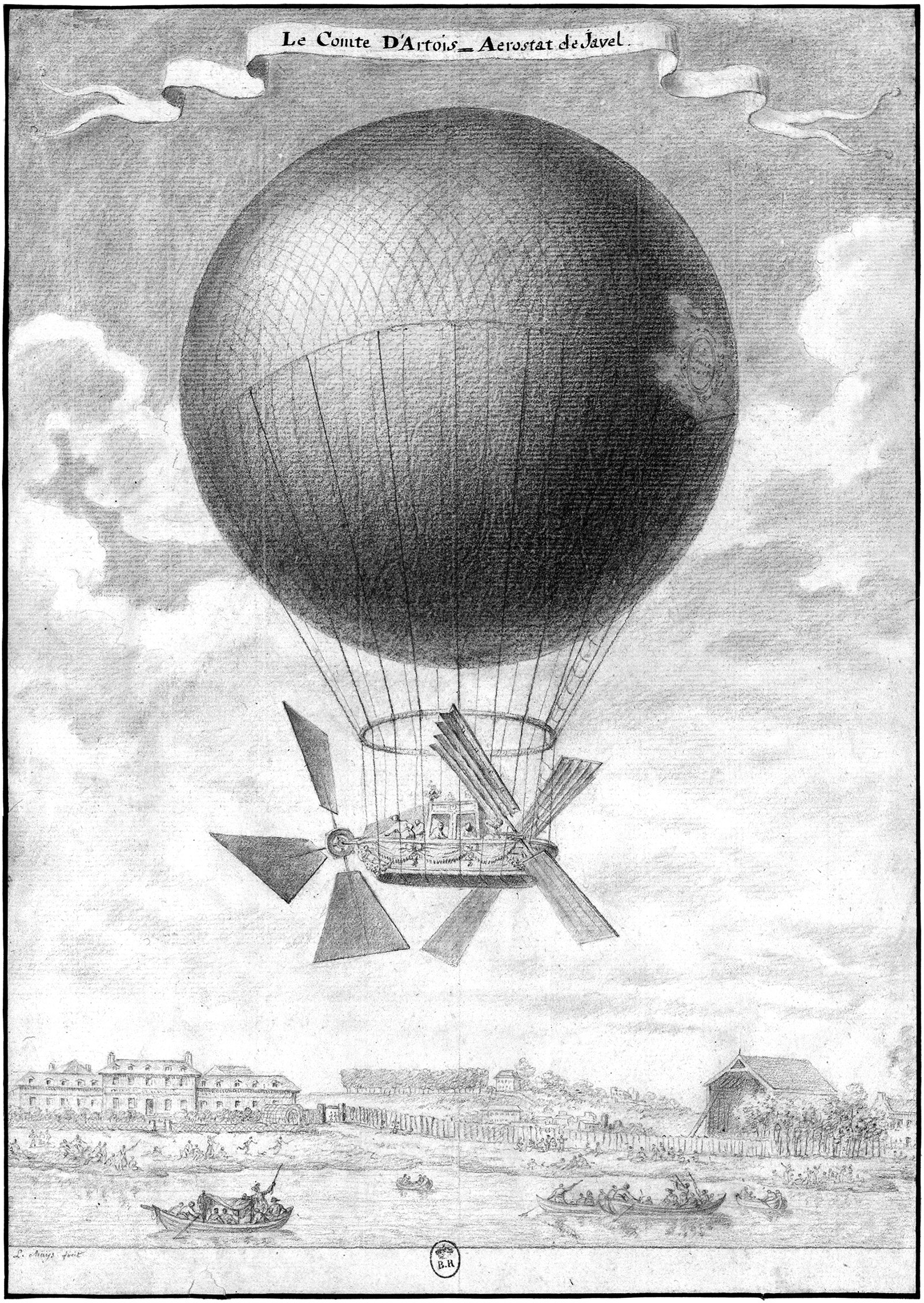

Alban & Vallet’s Comte d’Artois

Pictured above is a design for a flying machine by Léonard Alban and Mathieu Vallet from 1785. It was called Comte d-Artois, or l'Aérostat de Javel. It had a helium-filled balloon which carried a gondola. At one end of the gondola was a large propeller and at the other end was a pair of paddles. The gondola could comfortably seat four people and resembled a shallow boat. Throughout 1785, Alban and Vallet made many successful flights around Paris with the craft, and they also made three notable advancements in ballooning technology along the way.

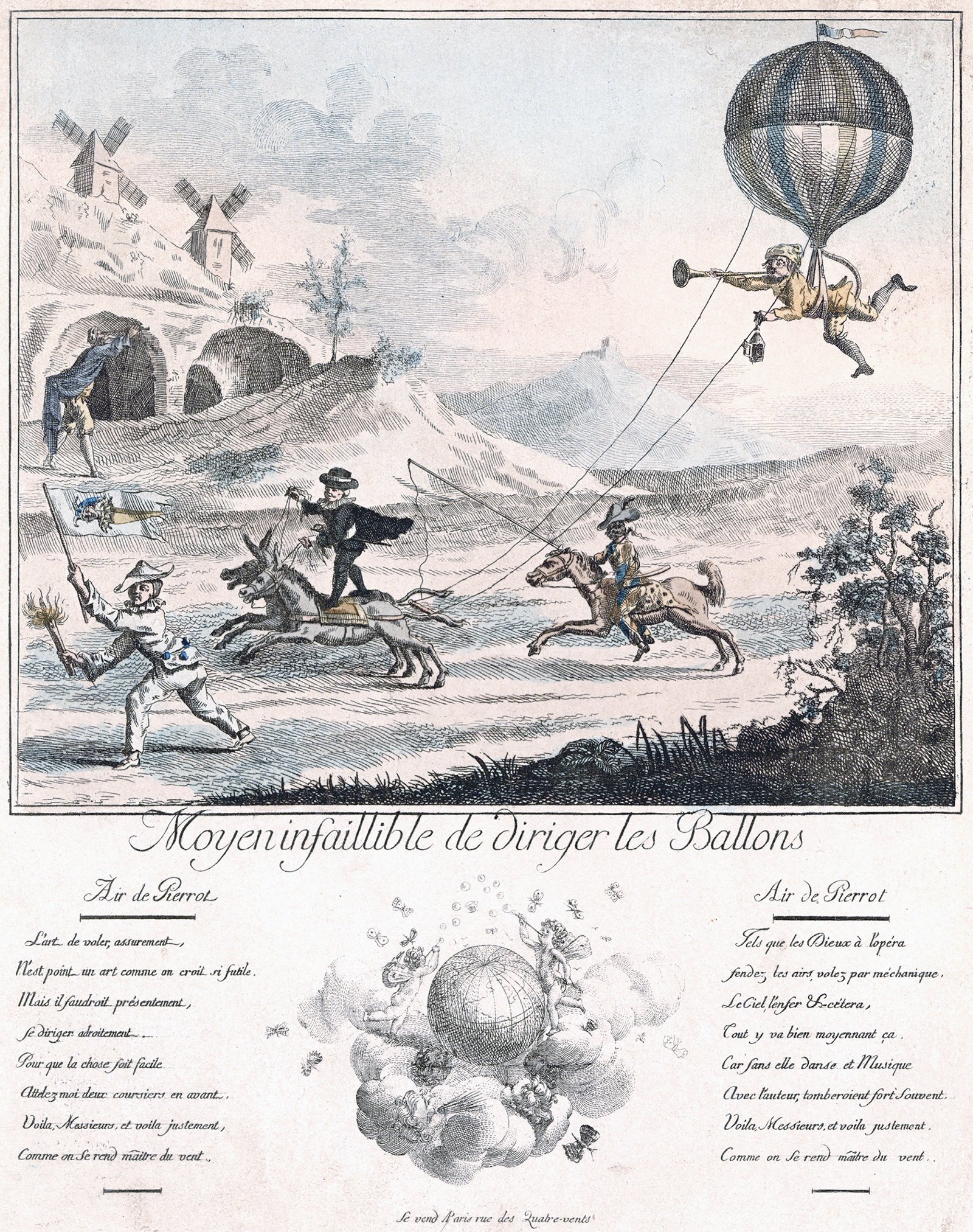

A Foolproof Way to Direct the Balloons

The above illustration shows a comical scene involving a man suspended from a balloon being pulled by a pair of horses. It was drawn in 1787 and it’s titled Moyen Infaillible de Diriger les Ballons, or A Foolproof Way to Direct the Balloons. It’s meant to be a satirical take on ballooning at the time, when flight was front-and-center on the public stage. The characters in the scene are from commedia dell'arte, which is a type of theatre with recurring archetypal characters.

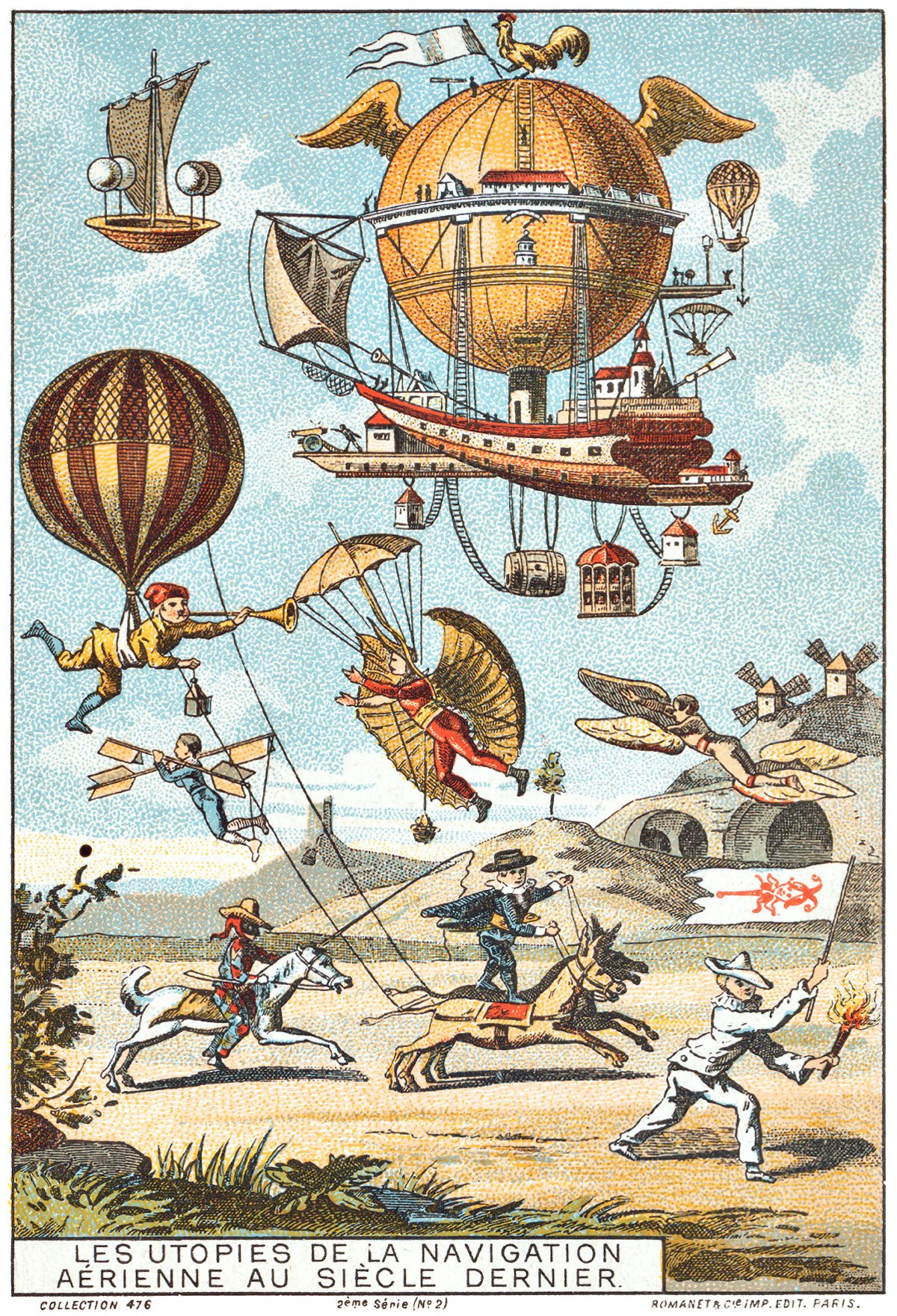

Utopian Flying Machines of the Previous Centuries

Pictured above is a French illustration from 1890, showing a collage of French flying machine ideas from the previous few centuries. The caption reads Les Utopies de la Navigation Aérienne au Siècle Dernier, which means The Utopia of Air Navigation in the Last Century. There are six flying machine ideas shown together in the sky.

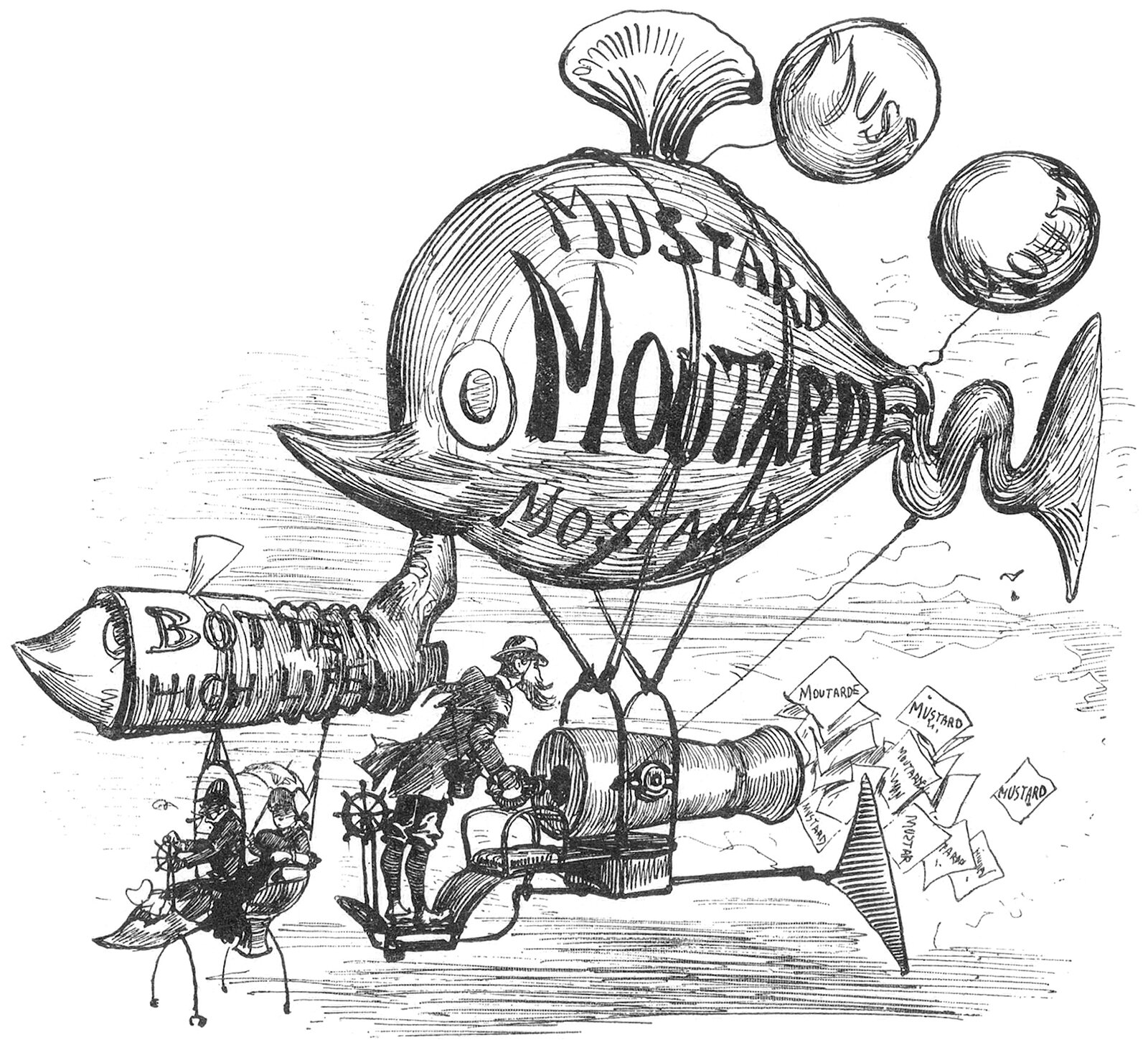

Albert Robida’s Flying Advertising Machines

The above illustration was drawn by Albert Robida for his 1883 novel Le Vingtième Siècle, or The Twentieth Century. The novel describes a future vision for Paris in the 1950’s, focusing on technological advancements and how they affected the daily lives of Parisians. Here, he shows a pair of flying machines meant for advertising.

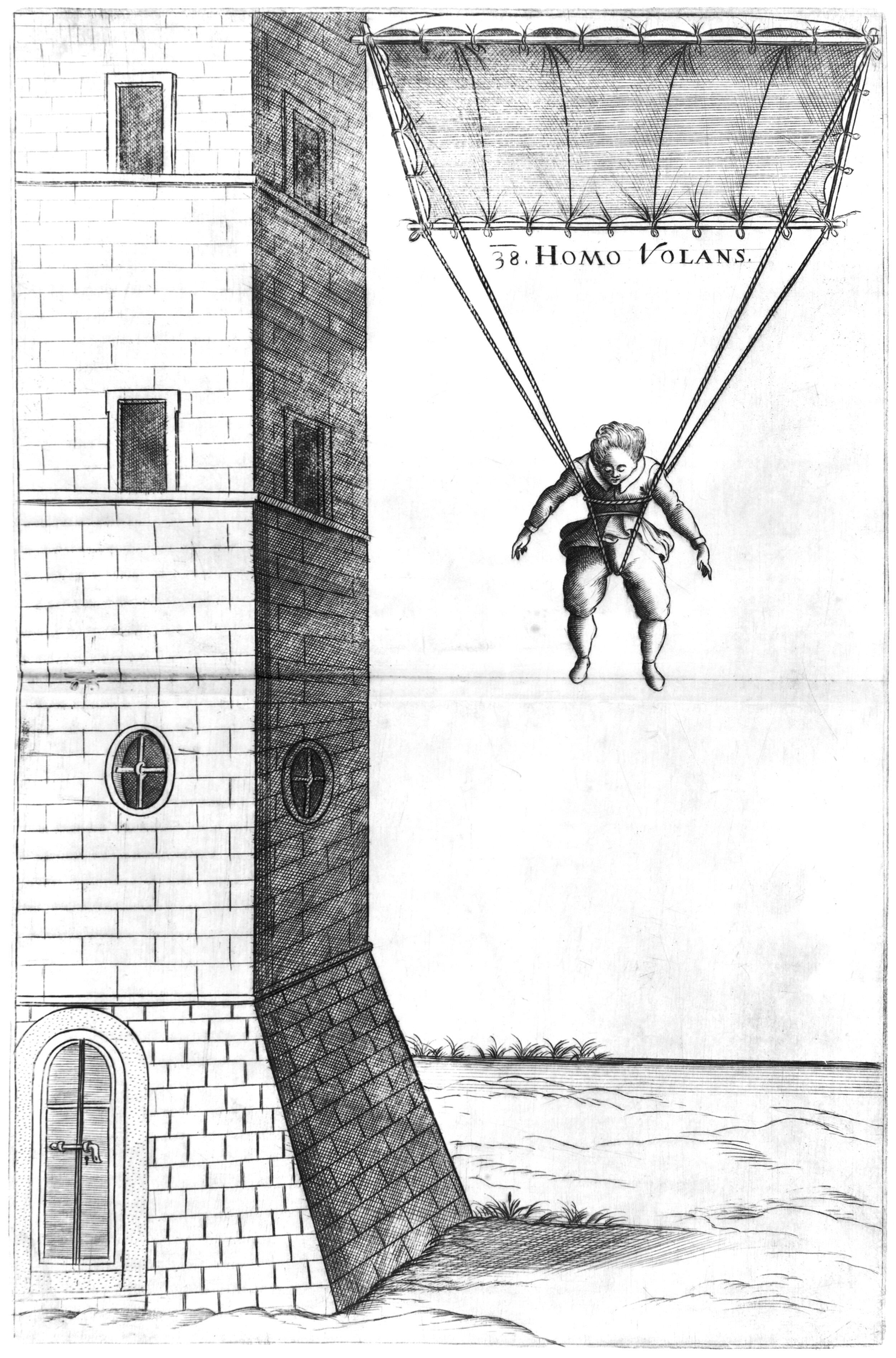

How to Fall : An Early History of the Parachute

Throughout the history of human flight attempts, the number one cause of death and injury has been a fall from a high place. In the early days of flight attempts, most examples involved jumping from a high perch and trying to stay in the aloft for as long as possible. Alongside these attempts at flight, others were concerned with the art of falling. How could a person leap from a high place and return to the surface safely? The resulting paths of thought make up the early history of the parachute.

What Goes Up, Must Come Down

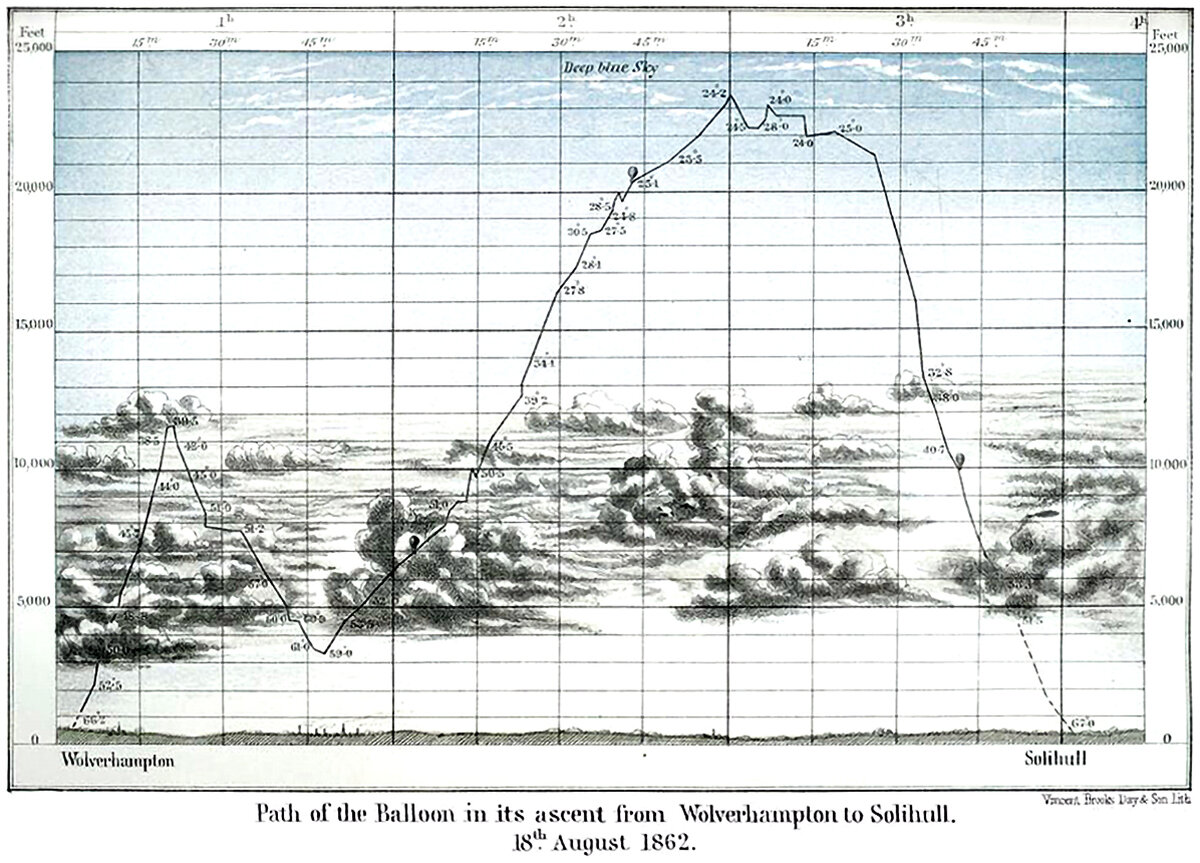

I love a drawing that tells a story. Here’s an illustration that does just that; it’s a diagram showing the flight path of James Glaisher’s balloon on 18 August 1862, which travelled between Wolverhampton and Solihull, just outside Birmingham in England. It’s essentially a graph that plots altitude over time, with some embellishments added for effect. The story being told is in the graph’s line, which ascends and descends just as the balloon did during its flight.

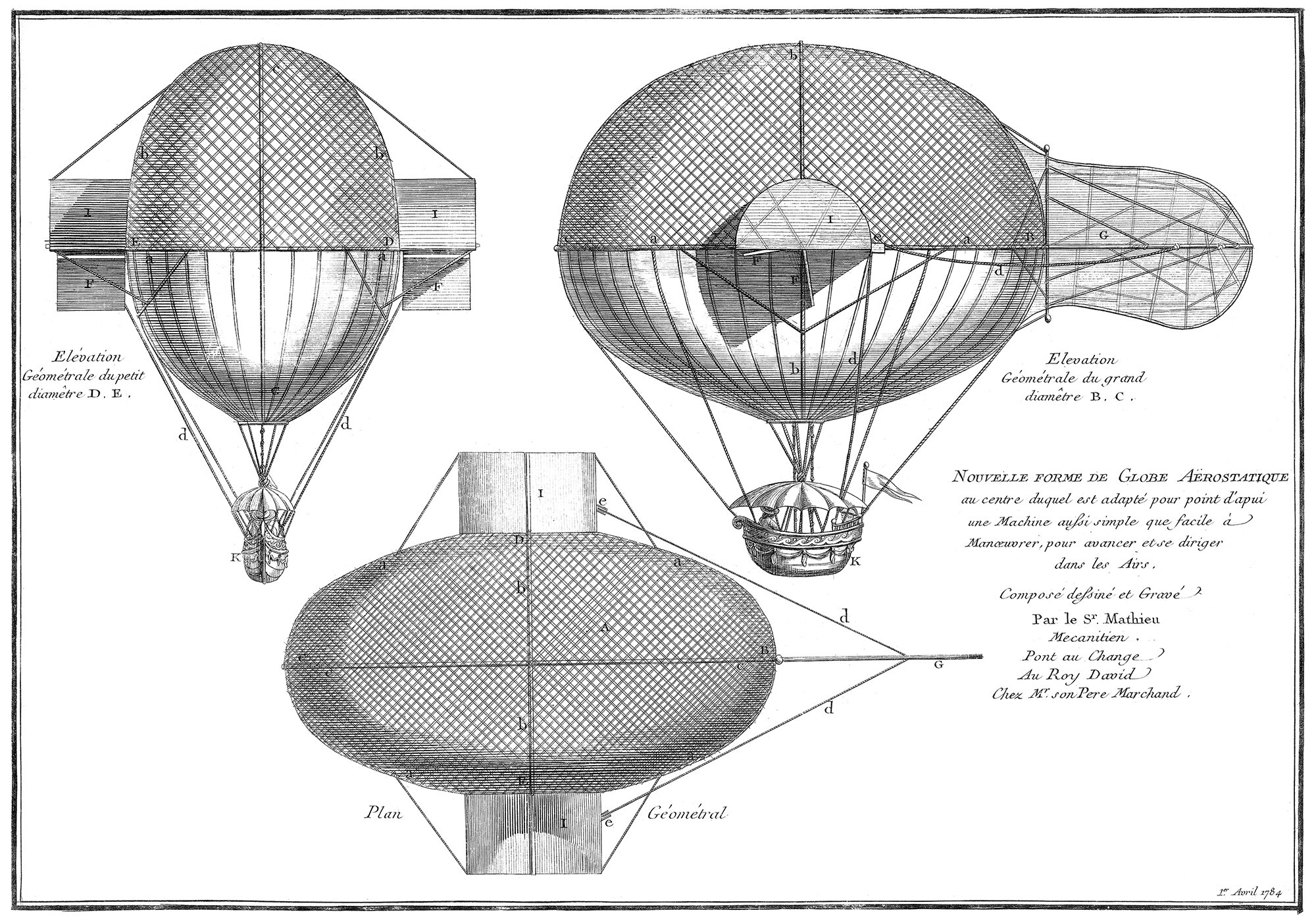

Jean Mathieu’s Aerostatic Balloon

This is a 1784 design for a finned balloon, designed by Jean Mathieu. It’s called Nouvelle Forme de Globe Aërostatique, which means New Shape for an Aerostatic Balloon. It’s an interesting one, because it’s unclear how it’s supposed to propel itself through the air. The design consists of an ellipsoidal balloon with a small basket underneath, housing two pilots, as well as two side hoods and one rear fin.

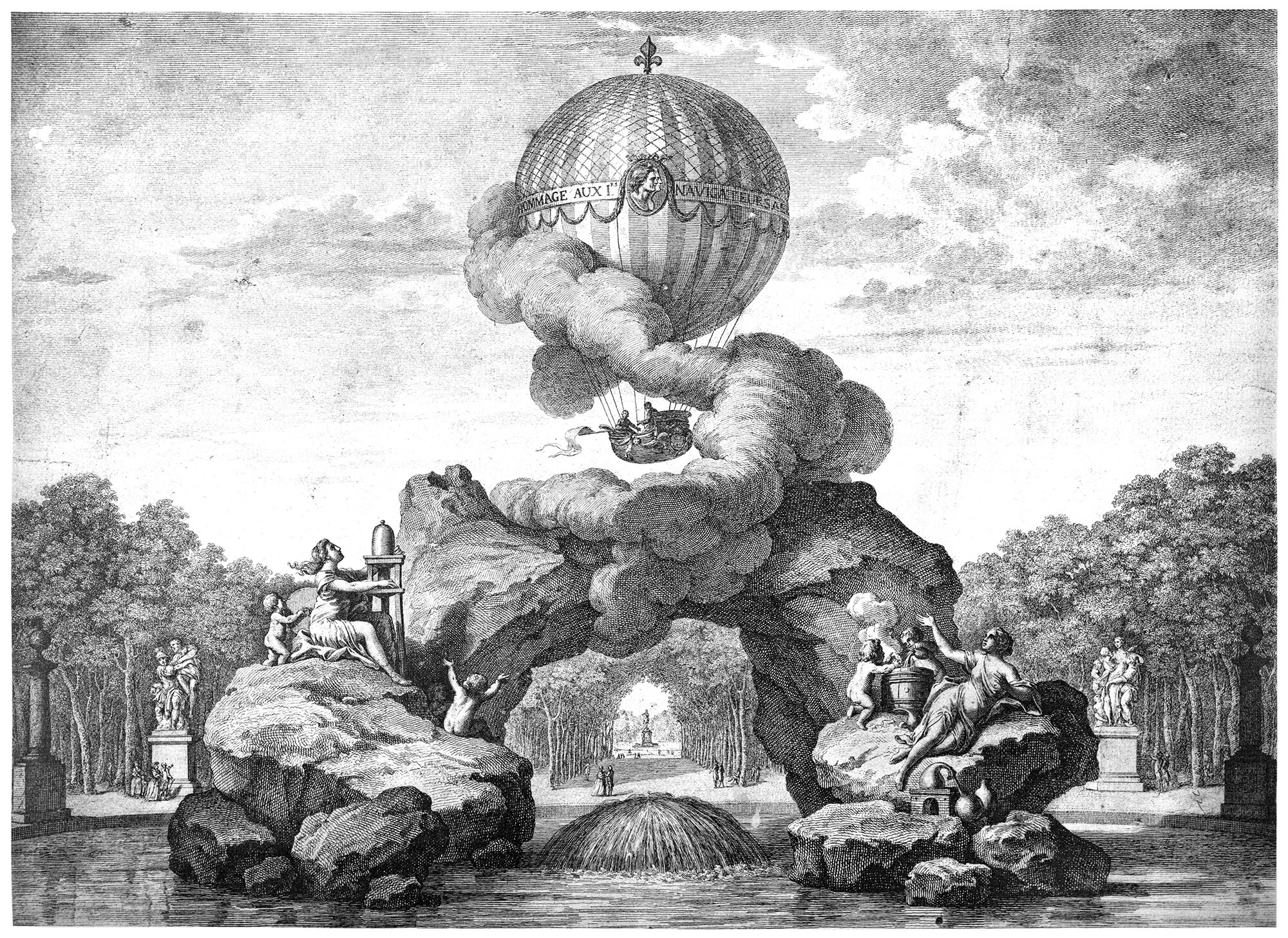

A Monument to the Glory of the First Aerial Navigators

Pictured above is the Projet d'un monument à la Gloire des Premiers Navigateurs Aériens, or the Monument to the Glory of the First Aerial Navigators. It was designed by an anonymous author for a site in the Tuileries Garden in Paris, and it consists of a stone arch placed in a fountain, with a balloon flying above it supported by a cloud-like form.

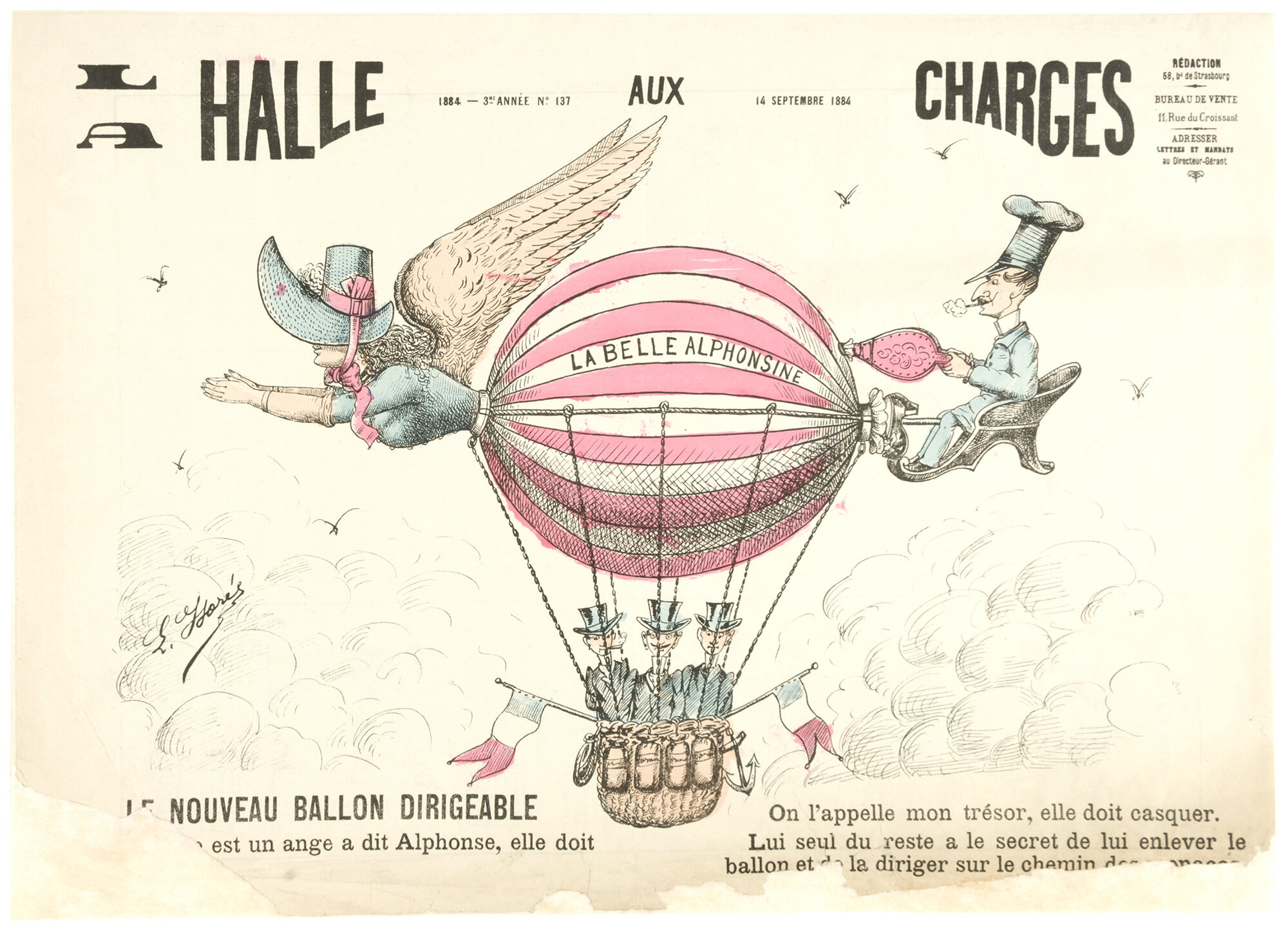

La Belle Alphonsine by E. Florés

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the human quest for flight was continuously on the public’s mind, and the above illustration is a testament to this. It’s from the front page of a French newspaper called La Halle aux Charges from 14 September 1884. This newspaper was well-known for it’s political caricatures and social commentary, and their choice to put a fictional balloon on their front cover is the perfect representation of what a successful flight means for all those involved.

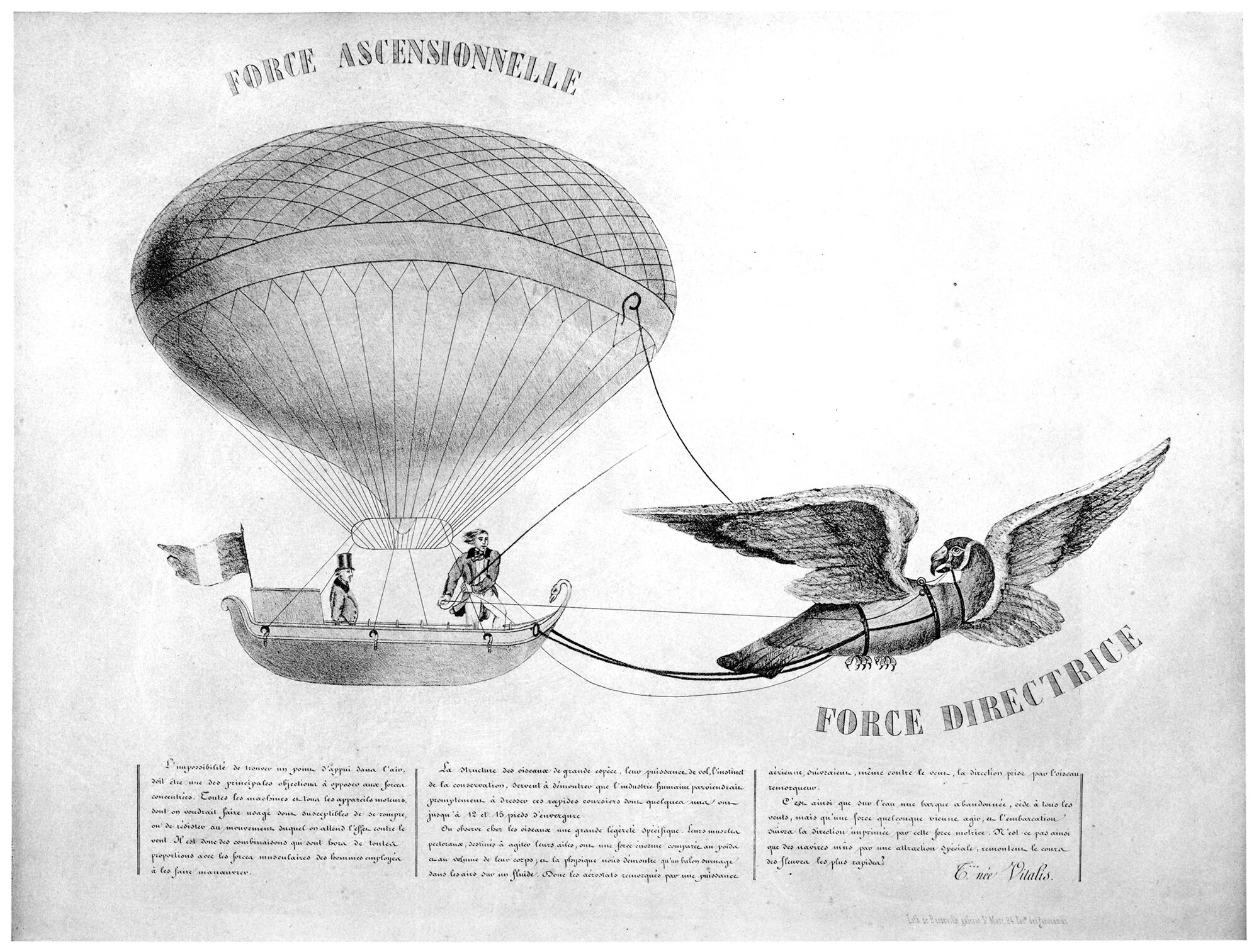

Tessiore’s Balloon Project Towed by a Tame Vulture

Pictured above is a design for a flying machine, consisting of a balloon pulled by a tame vulture. It was originally published in 1845, and was re-published in 1922 in the book L’Aeronautique des origines a 1922. The title of the illustration is Projet de Ballon Remorqué par un Gypaète Spprivoisé, or Project for a Balloon Towed by a Tame Vulture. I’m unable to find any data on the image apart from this, but the content itself is enough to discuss, for obvious reasons.

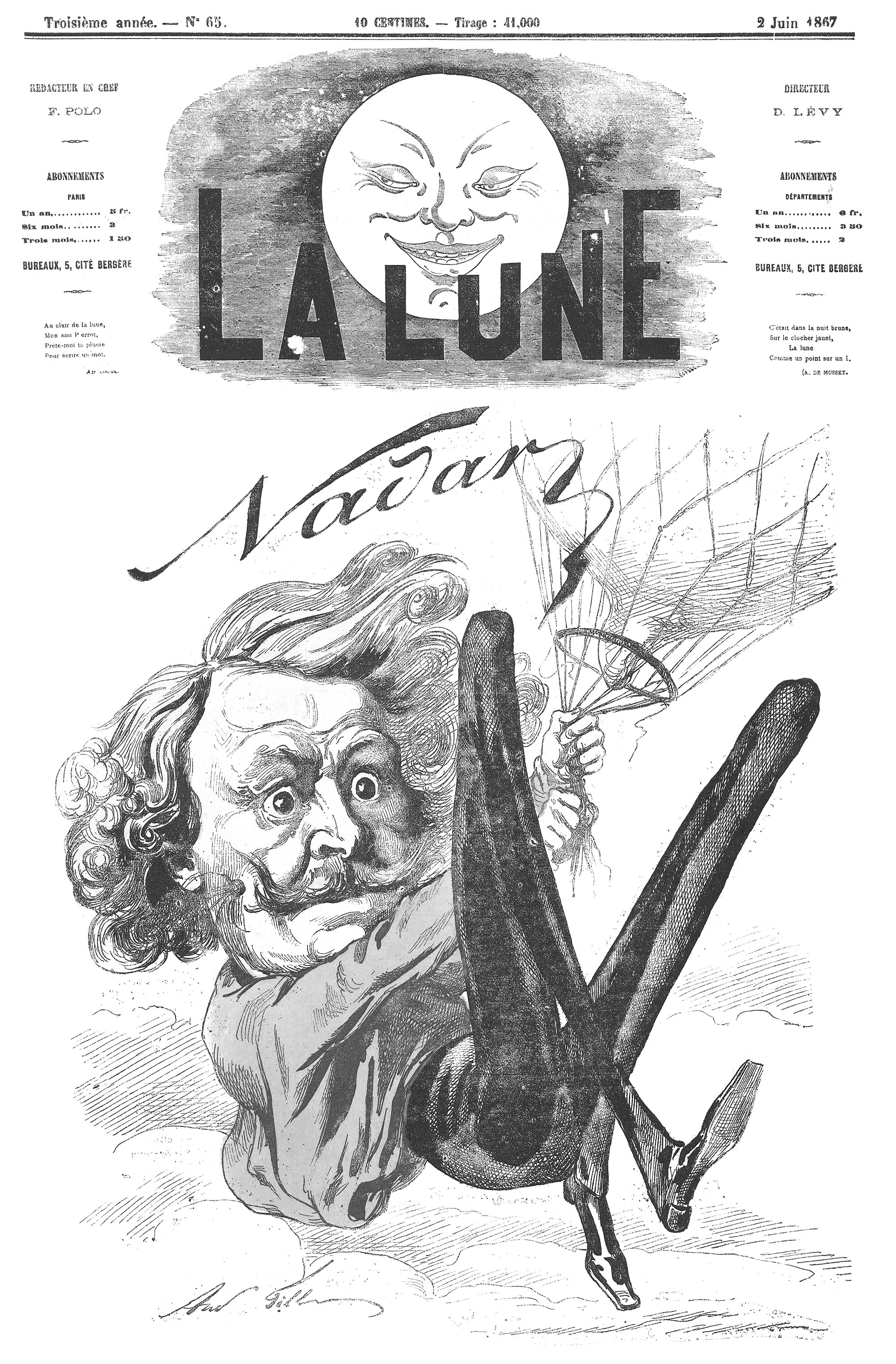

Nadar and the Aerial Perspective

Pictured above is Gaspard-Félix Tournachon, better known by the pseudonym Nadar, who was a French photographer in the nineteenth century, just when aeronautics and air travel were entering popular culture. He was fascinated by human flight, and in 1858 he became the first person to successfully take aerial photographs while he was in a balloon. He subsequently commissioned balloons to be designed and built, and he would allow passengers to take flights with him. He was no doubt obsessed with verticality, and his aerial photographs mark a major turning point in the history of human flight.

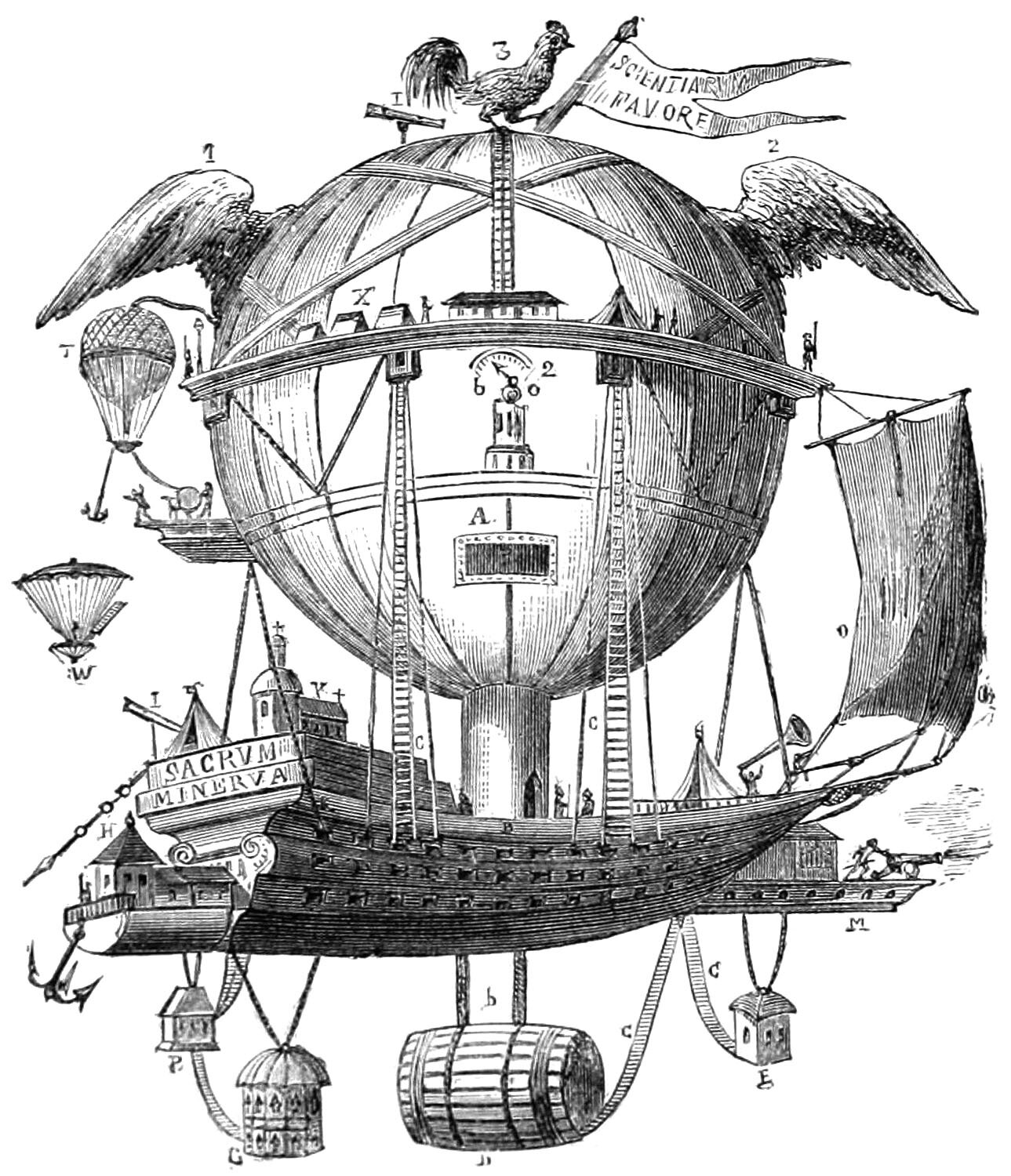

Étienne Gaspard Robert’s La Minerve Airship

Pictured above is an airship design from 1803 by Étienne Gaspard Robert. Robert was a Belgian stage magician and physicist, and he also designed and flew balloons. His most famous design, called La Minerve, is pictured above. It was meant to be an exploratory vessel which would make multi-month trips around the world. Robert described the craft as an aerial vessel destined for discoveries, and proposed to all the Academies of Europe. It’s impractical, naïve, and amazing.

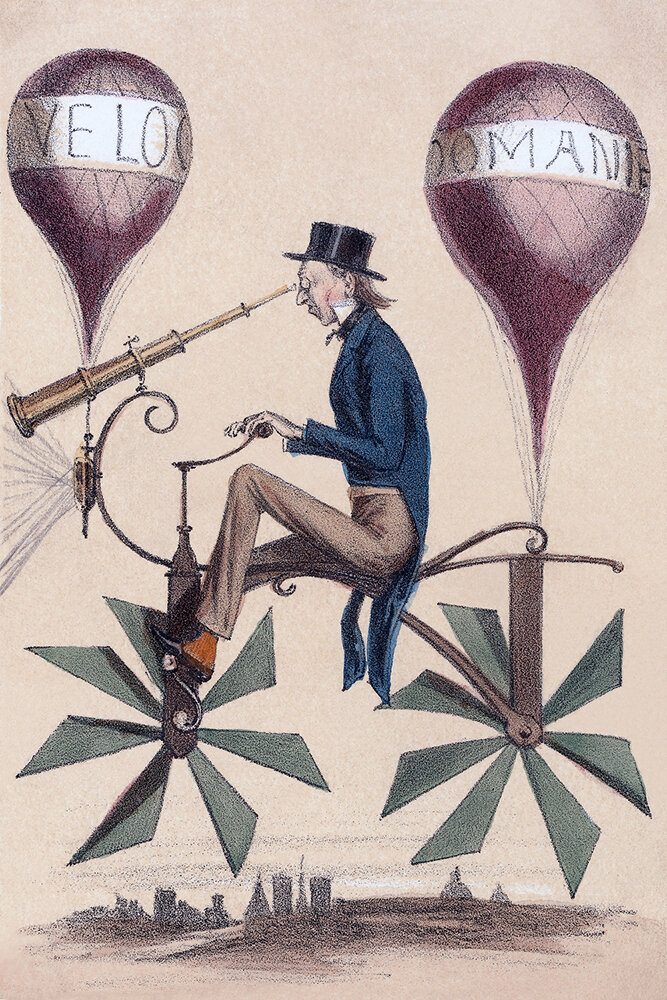

A Voyage to the Moon

There’s a fine line between fiction and invention. Throughout my research into flying machines, I’ve come across many fictional designs that weren’t meant to actually fly, but to evoke the idea of flight. The above cartoon is one of these. It’s a French cartoon from 1867, titled Voyage a la Lune, or Voyage to the Moon. It riffs on the idea of a bicycle that flies, and it’s got a playful feeling about it, as if it doesn’t take itself seriously.

Those Wacky Victorian Flying Machines

Throughout my research into the history of flight and flying machines, I’ve come across a few examples that I cannot find any description or context for. I’m calling them Victorian because they’re illustrated in a similar style to that time period, but I’ve been unable to date them with any certainty. If anyone has any information about these contraptions or their creators, please let me know!

A Suggestion for a Flying Machine

The above illustration appeared in an 1877 issue of The Graphic, with the simple headline “A Suggestion for a Flying Machine”. Without any context or description, we can only take the image at face value. The machine seems to be lifted by a group of balloons placed centrally between two large wings, and the pilot dangles from a pole at the center of it all. Said pole has a tail behind it, and the pilot’s arms and legs control the tail and the wings, respectively.

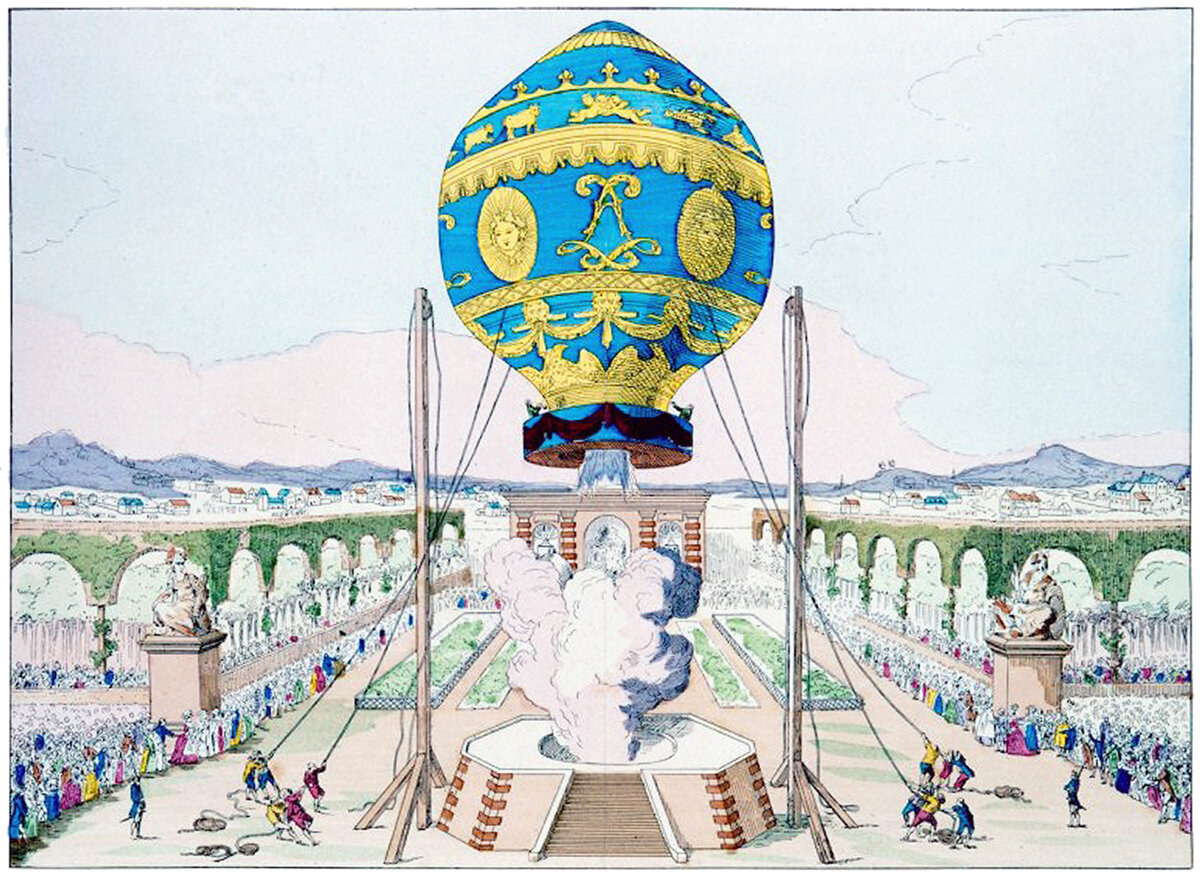

The Montgolfier Brothers and Their Balloons

The Montgolfier Brothers are credited with the first ever successful balloon flight with a human pilot. Pictured above, the flight took place in Paris in 1783. The brothers, Joseph-Michel and Jacques-Étienne, were born into a family of paper manufacturers, but became obsessed with flight after observing clothes drying over an open fire. Together, they subsequently experimented with flight and invented the Montgolfière-style hot-air balloon.

Early Balloon Designs

There are two main strategies when designing a flying machine. The first is a heavier-than-air machine, which relies on creating a lifting force to overcome gravity. The second is a lighter-than-air machine, which relies on a balloon filled with gas or heated air. The above illustration shows famous examples of the latter.

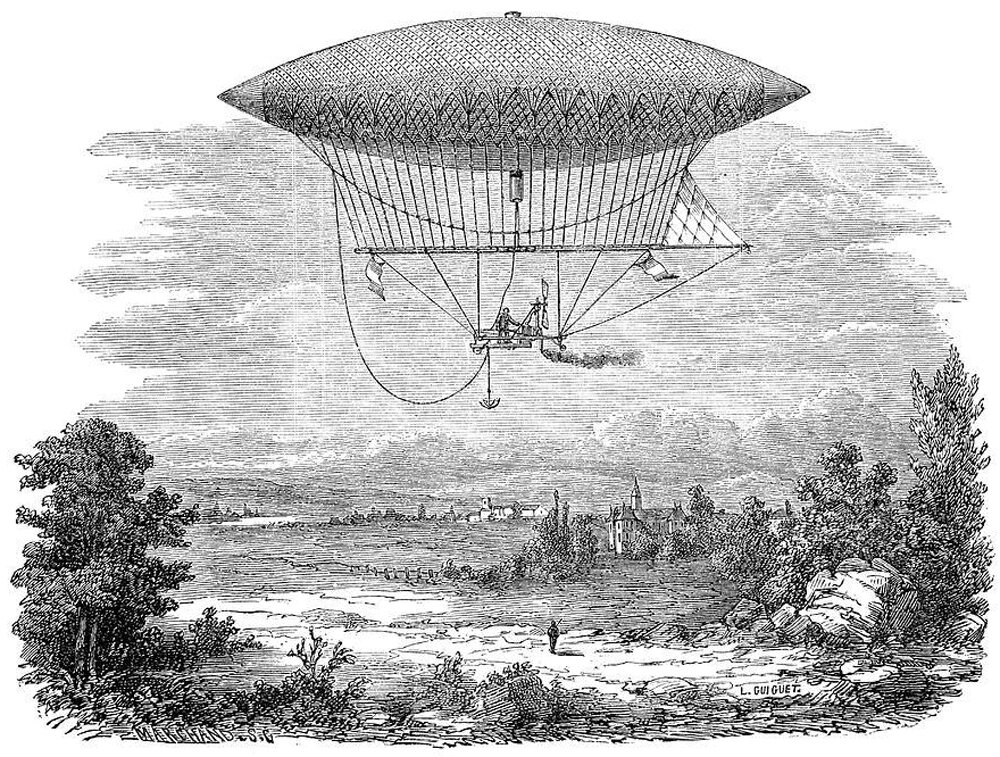

Henri J. Giffard's Airship and Captive Balloon

The airship pictured above was invented by Henri Giffard, which first flew in 1852 from Paris to Élancourt, a journey of 27 km (16.7 miles). I love this image because of the single, solitary figure in the foreground, staring up at the massive airship floating in the sky above. There’s something inspiring about the scale of the two human figures shown, one on the ground looking up, and the other controlling the airship as it floats by, looking down on the landscape below. I see Henri Giffard’s work as an attempt to bring these two worlds closer together.