The First Ascent of the Matterhorn

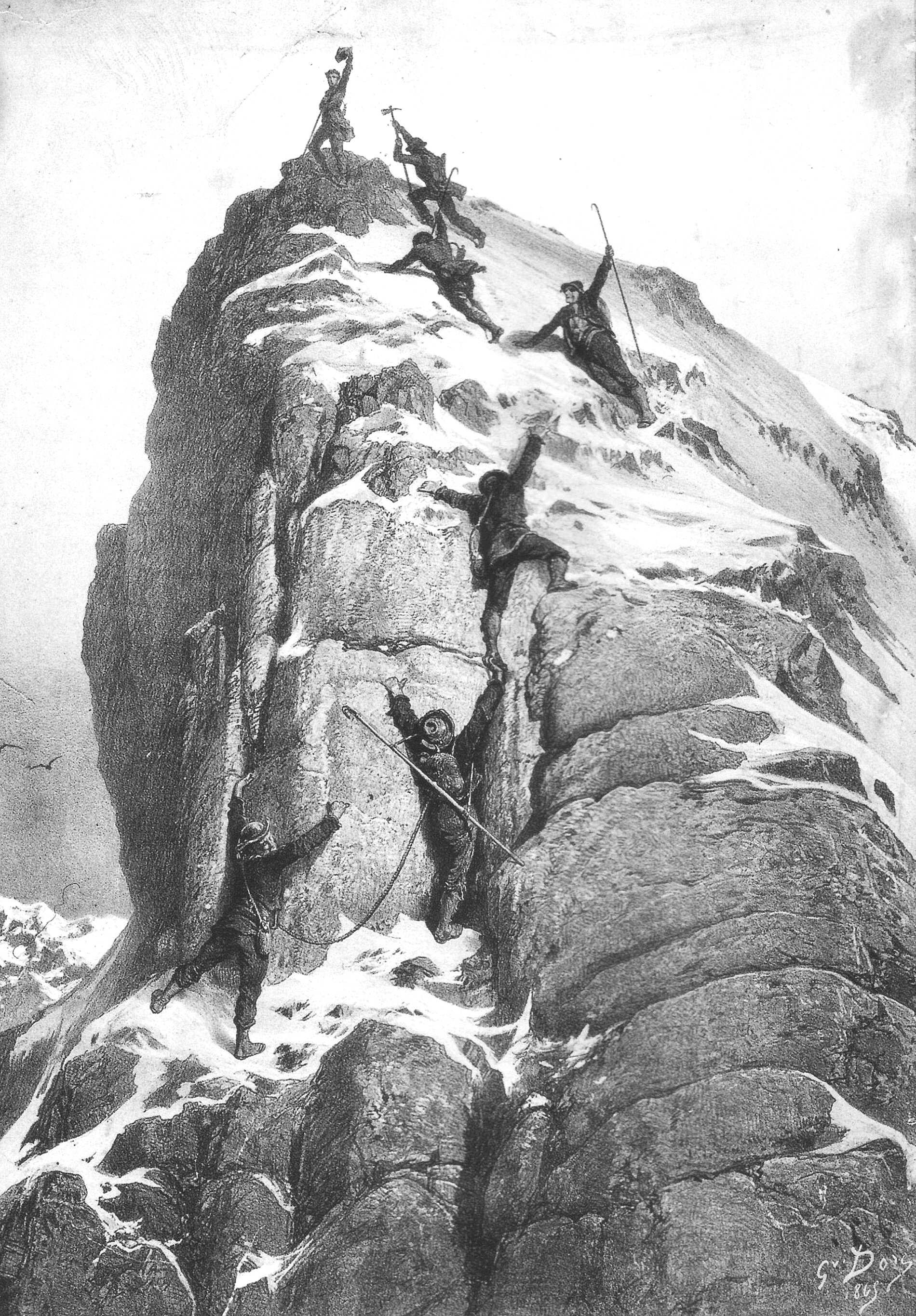

Illustration by Gustave Doré showing the first successful summit of the Matterhorn in 1865. The expedition involved seven climbers and was led by British mountaineer Edward Whymper.

There are few mountains in the world as instantly recognizable as the Matterhorn. Located in the Swiss Alps, this majestic pyramid of gneiss straddles the border between Switzerland and Italy and looms over the Swiss mountain town of Zermatt. Due to its location and visibility, it is legendary within the history of mountaineering. In the 1860’s it was the focus of an international competition to be the first to reach its summit. This story, which includes the first successful summit of the mountain, is a tale of triumph and tragedy, and it serves as a cautionary tale for mountaineers to this day.

The first ascent of the Matterhorn marked the end of the golden age of alpinism. This refers to the decade between 1854 and 1865 during which many of the great peaks in the alps were first summited. It began with an ascent of the Wetterhorn in 1854 by a team led by Alfred Wills, and it ended with the first ascent of the Matterhorn in 1865 by a team led by Edward Whymper.

Edward Whymper was a British artist-turned-mountaineer who, from 1861 to 1865, made several attempts to summit the Matterhorn. He initially teamed up with Italian guide Jean-Antoine Carrel, but over time they would became competitors. The Matterhorn was the tallest unclimbed peak in the Alps at the time, and Carrel came to believe a native Italian, not a Brit, should be the first to set foot on the summit. In 1865, while preparing for a summit attempt along the southwest ridge, Carrel withdrew at the last moment to lead an Italian team up the Italian side of the mountain. He had been recruited by Felice Giordano of the Italian Alpine Club, and the defection marked the end of the partnership between Whymper and Carrel.

Illustration by Cyrus Johnson from 1871 showing the summit pyramid of The Matterhorn. In the foreground are three mountaineers, utterly dwarfed by the massive mountain.

After Carrel defected to Giordano, Giordano snatched up the best guides in Zermatt and left the town to plan his expedition. This left Whymper without a climbing team. He networked around town and put together a patchwork team of climbers which included Lord Francis Douglas, Peter Taugwalder and his sons, Peter and Joseph, Michel Croz, Charles Hudson, and Douglas Hadow. Together, they set off on 13 July to make their attempt on the summit.

They first climbed up to 3,380 meters (11,090 feet) and set up a bivouac for the night. This would serve as their base camp. The next morning, they set off at dawn with Joseph Taugwalder returning to Zermatt. The seven remaining men ascended the east face without incident, and at 09:55 they reached the foot of the upper peak, at roughly 4,265 meters (14,000 feet). They crossed over the ridgeline to the north face and ascended until the slope eased off. At this point, Whymper and Croz made a mad dash for the summit, and reached it at the same time. After checking for any evidence that others were there before them, they spotted Carrel’s party on the opposite ridge, still 200 meters below the summit. Carrel then spotted them on the summit, and after realizing they had successfully summited, he accepted his defeat and turned around. Whymper and his team stayed on the summit for roughly an hour before beginning their descent.

Illustration by Gustave Doré showing the fall that followed the first successful summit of the Matterhorn in 1865. After a slip on the rocks, an old rope broke, sending four climbers to their death after falling down the north face of the mountain.

They descended in a rope line, with Michel Croz first, followed by Douglas Hadow, Charles Hudson, Lord Francis Douglas, Peter Taugwalder senior, then junior and Whymper last. About an hour into the descent, Hadow slipped and fell into Croz. The two men fell, pulling Hudson and Douglas along with them. Whymper and Taugwalder were able to brace themselves by the time the rope caught them, and for a few short moments they held the men below them. Then the rope broke under Taugwalder, and the four lower men subsequently fell to their deaths.

Whymper and the Taugwalders composed themselves, fixed some rope to the rocks, and resumed their descent. They made it back to Zermatt on the morning of 15 July. The following day a rescue expedition, which included Whymper, went back up the mountain. The bodies of Croz, Hadow and Hudson were found, and were brought down on 19 July. The body of Douglas was never recovered. In the aftermath of the tragedy, it was discovered that the rope between the survivors and the four men that fell was the oldest and weakest they had brought with, only meant as a reserve. This is why it broke under the weight of the four men. The survivors couldn’t say why that rope had been used in lieu of a stronger one. It was most likely a simple oversight, which could’ve been meaningless had the men not slipped and fallen the way they did.

Whymper’s expedition is a tragic tale that highlights the dangers of mountaineering, and the outcome is fraught with what-ifs. What if the correct ropes were used to tie all the members together? What if the team had tied into the rocks along the way as a safety precaution? What if Hadow hadn’t slipped in the first place? What if he slipped, but the rope had held? These questions are easy to ask after the fact, but I suspect the elation of reaching the summit, combined with tired muscles and minds made it much easier to mix up the ropes and to miss a step.

The business of climbing mountains is a dangerous one, and the first ascent of the Matterhorn is a stark reminder of this. It’s a testament to the power of mountains and verticality that these men decided to risk their lives in the pursuit of the Matterhorn summit. They reached it, thus cementing their names into the history books, but some of them never returned to the valley below. Michel Croz, Douglas Hadow, Charles Hudson and Lord Francis Douglas will forever be linked to the Matterhorn, both for their triumph at the summit and the tragedy that soon followed.

Check out other posts about mountaineering here.