Welcome to On Verticality. This blog explores the innate human need to escape the surface of the earth, and our struggles to do so throughout history. If you’re new here, a good place to start is the Theory of Verticality section or the Introduction to Verticality. If you want to receive updates on what’s new with the blog, you can use the Subscribe page to sign up. Thanks for visiting!

Click to filter posts by the three main subjects for the blog : Architecture, Flight and Mountains.

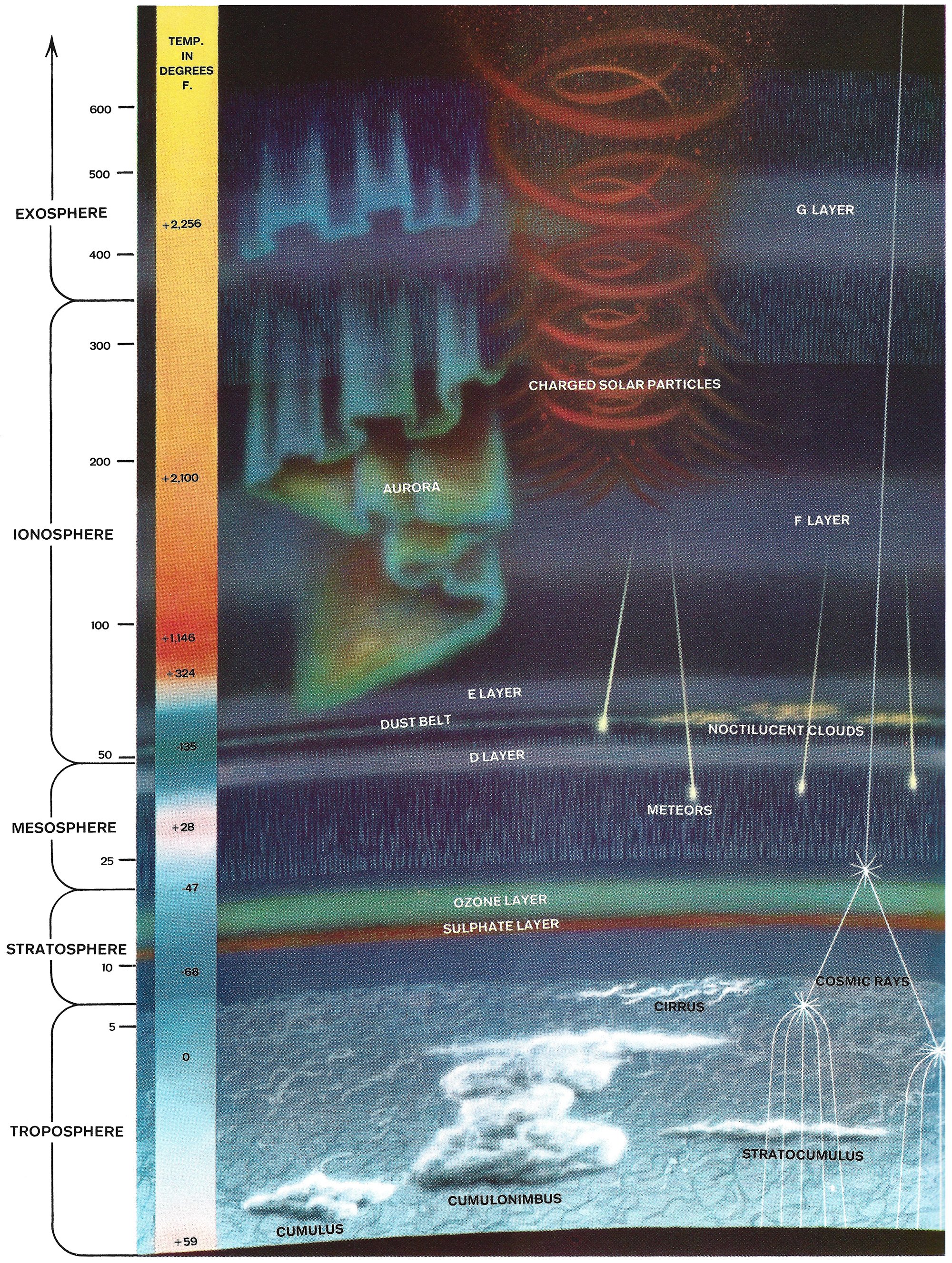

The Many-Layered Atmosphere

The above illustration originally appeared in the 1962 book The Earth from the Life Nature Library. It does a masterful job of explaining the complex layers of the earth’s atmosphere, and it puts the scale of each layer in perspective.

“Thousands of tired, nerve-shaken, over-civilized people are beginning to find out that going to the mountains is going home.”

-John Muir, Scottish naturalist and mountaineer, 1838-1914

The Verticality of Clouds

I recently climbed Mount Saint Helens in Washington state, and the experience brought me face-to-face with the verticality of clouds. The photo above was taken just after dawn, and you can see two very different types of clouds in the sky. Just above my head was a dense, thin layer of altostratus clouds, which looked solid and dark from below. Far above this was a wispy pattern of cirrus clouds, which was much lighter in appearance. In addition to these, there were also groups of low-lying stratus clouds in the valleys below. What struck me in that moment was each of these cloud types was created by the exact same elements, the only difference was their height above the surface.

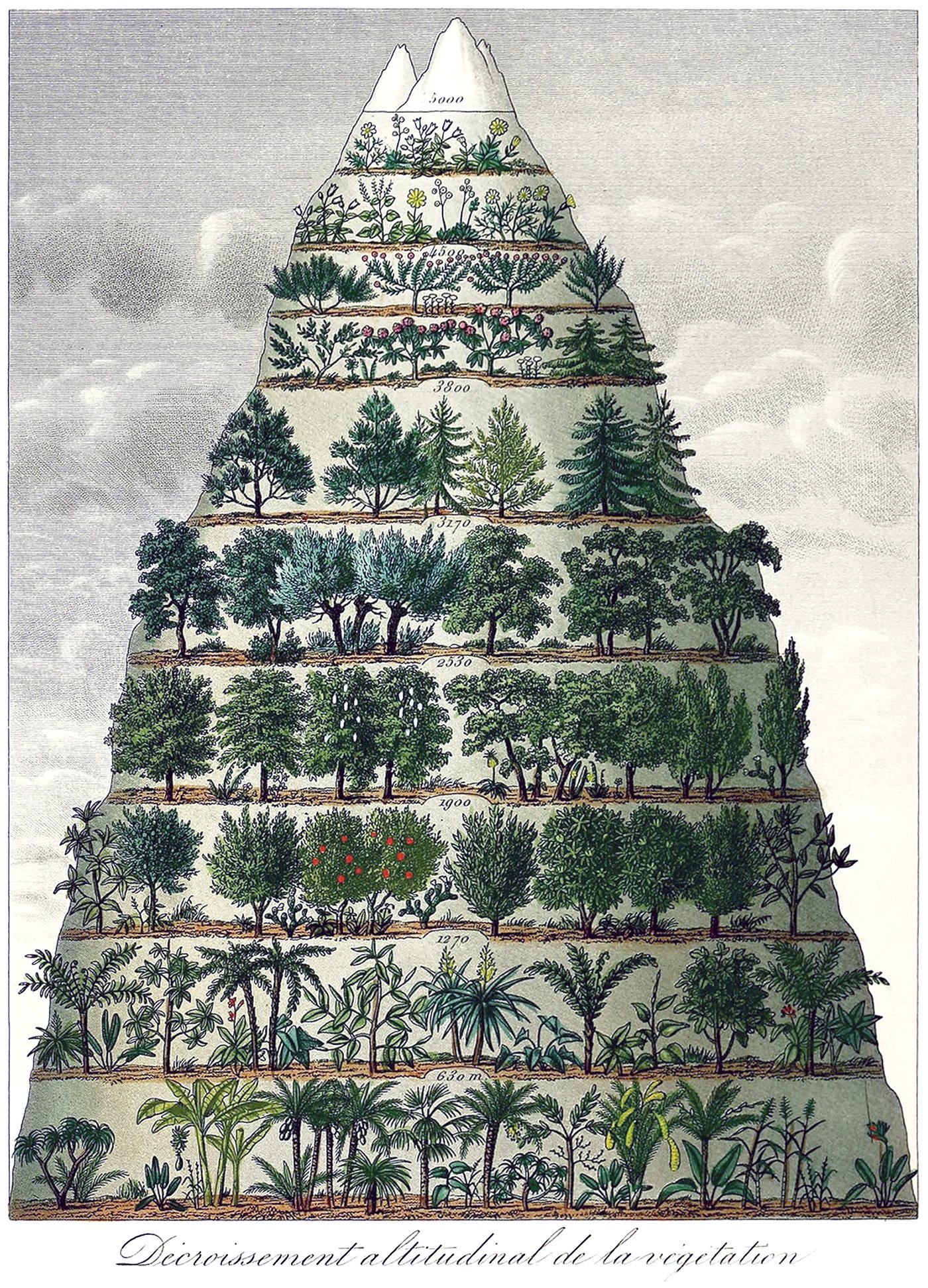

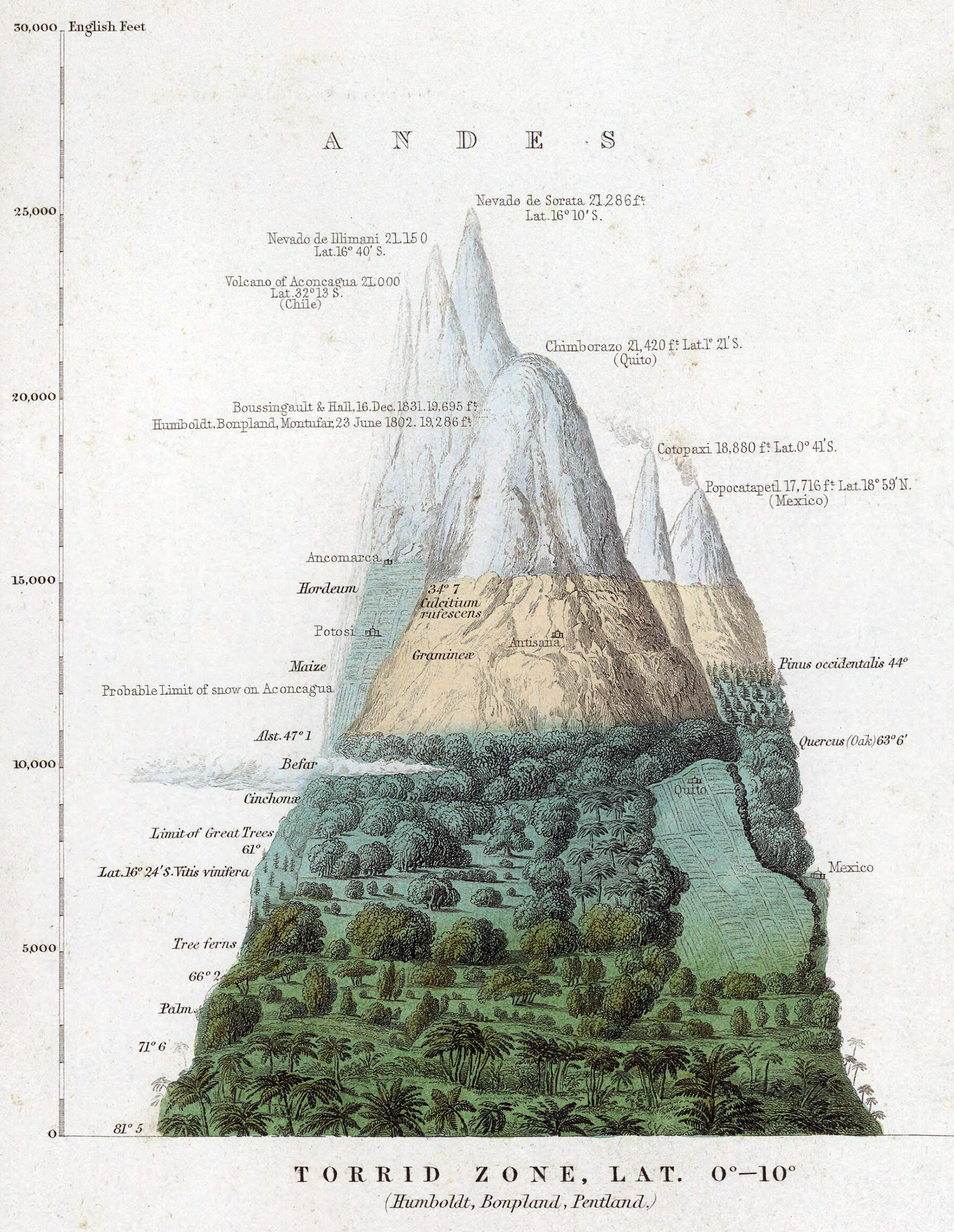

The Altitudinal Decrease in Vegetation

Pictured above is an illustration from the 1860s by Jean-Augustin Barral, titled Décroissement Altitudinal de la Végétation, which is French for The Altitudinal Decrease in Vegetation. It’s a beautiful work that attempts to categorize vegetation types by elevation, which is known as altitudinal zonation. Barral gets the overall concept correct, but we now know the details to be much more nuanced and complex than his drawing suggests.

“The union of altitude and solitude fills me with an arrogant sense of ownership. After all, the sky is my domain.”

-Philippe Petit, French high-wire artist, born 1949.

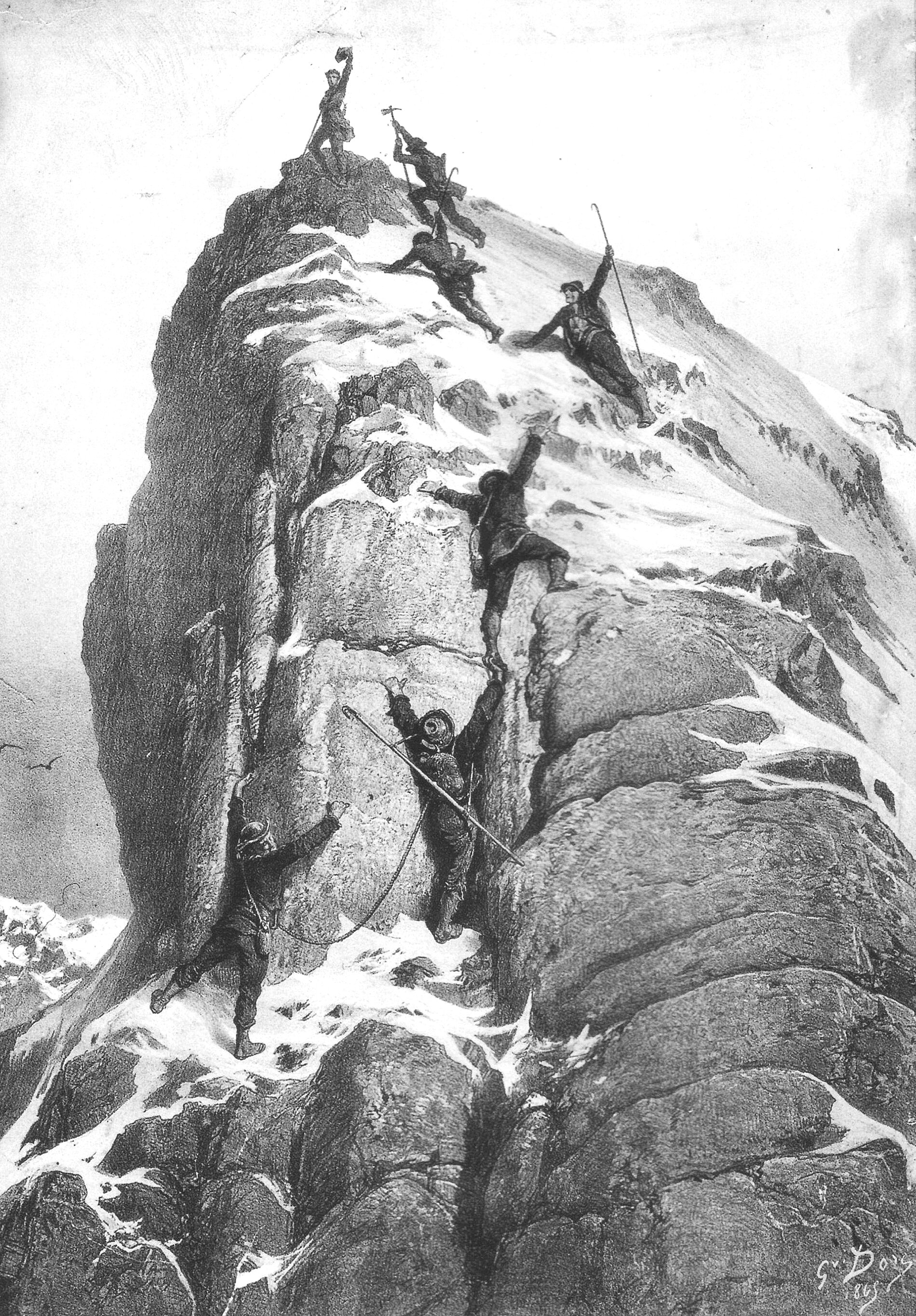

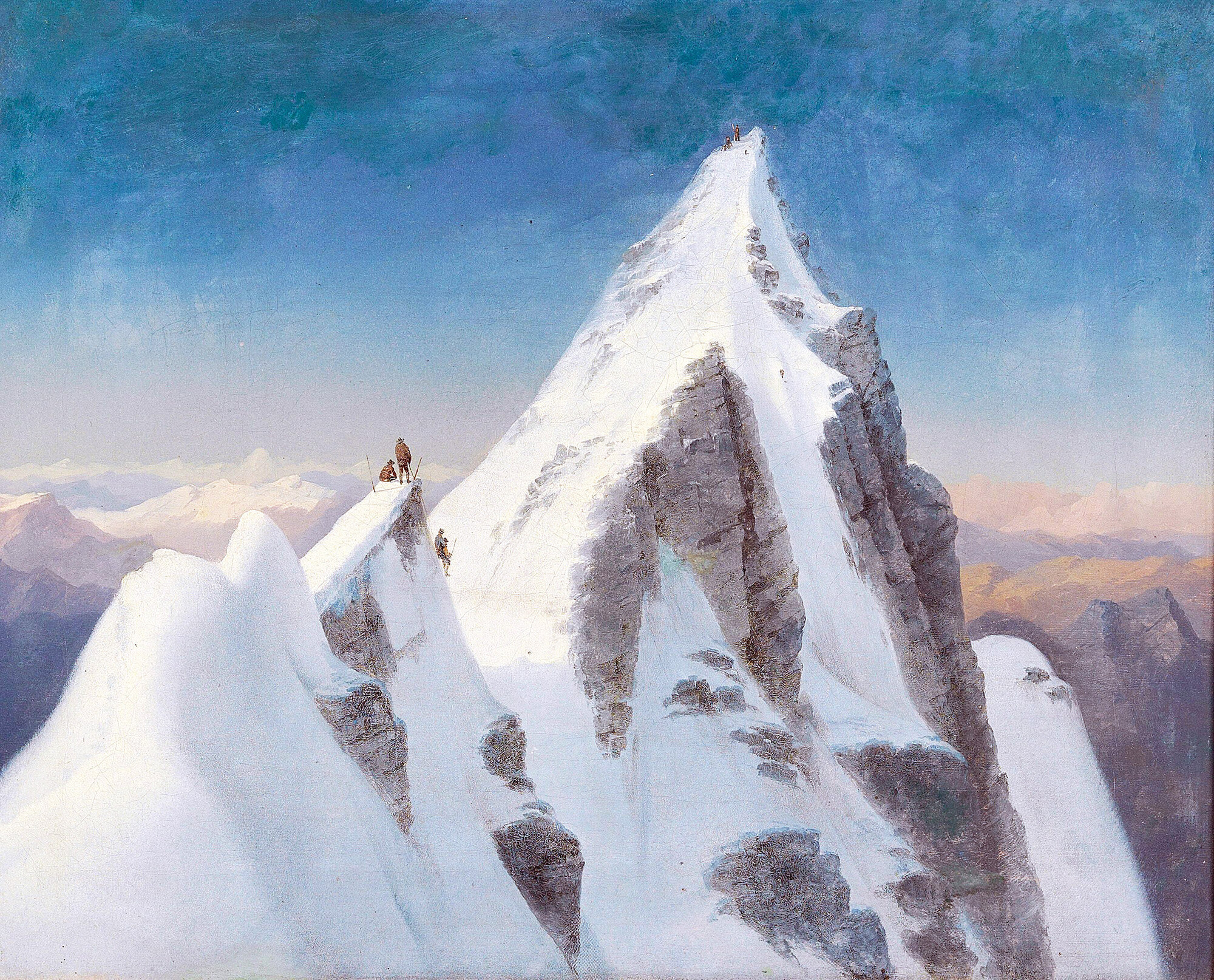

The First Ascent of the Matterhorn

There are few mountains in the world as instantly recognizable as the Matterhorn. Located in the Swiss Alps, this majestic pyramid of gneiss straddles the border between Switzerland and Italy and looms over the Swiss mountain town of Zermatt. Due to its location and visibility, it is legendary within the history of mountaineering . In the 1860’s it was the focus of an international competition to be the first to reach its summit. This story, which includes the first successful summit of the mountain, is a tale of triumph and tragedy, and it serves as a cautionary tale for mountaineers to this day.

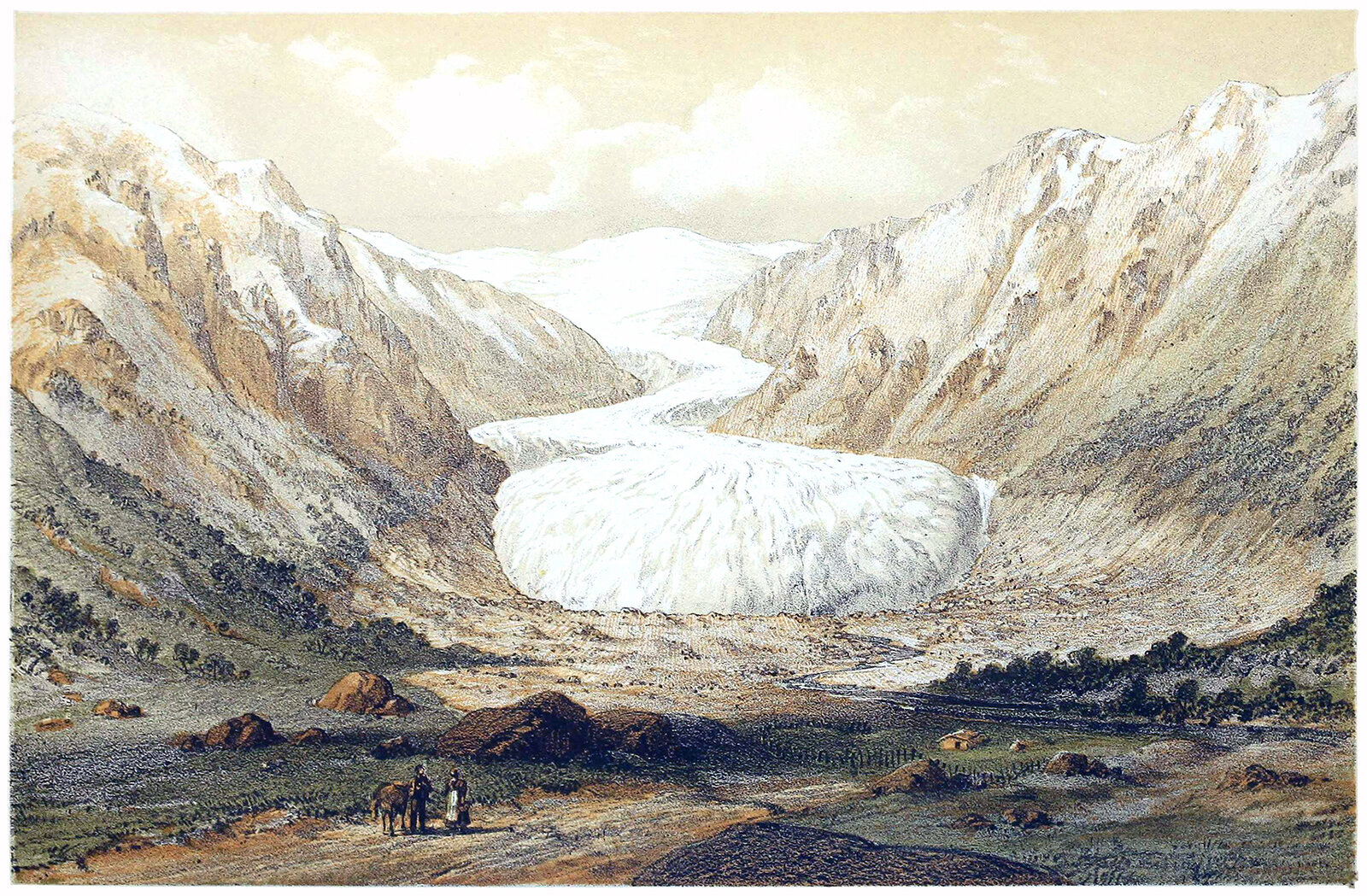

Mountains and Glaciers

The relationship between mountains and glaciers is a fascinating one. Where glaciers exist, the morphology of a mountain created the conditions necessary for a glacier to form. Once formed, a glacier’s growth and movement will slowly erode away the very mountain that created it. Over time, this movement carves and changes the landscape, resulting in moraines, cirques, fjords, and various other landforms.

“The airplane has unveiled for us the true face of the earth. For centuries, highways had been deceiving us. They shape themselves to man’s needs and run from stream to stream.”

-Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, French writer and aviator, 1900-1944.

“It is because [mountains] have so much to give and give it so lavishly to those who will wrestle with them that men love the mountains and go back to them again and again.”

-Sir Francis Younghusband, British explorer and mountaineer, 1863-1942.

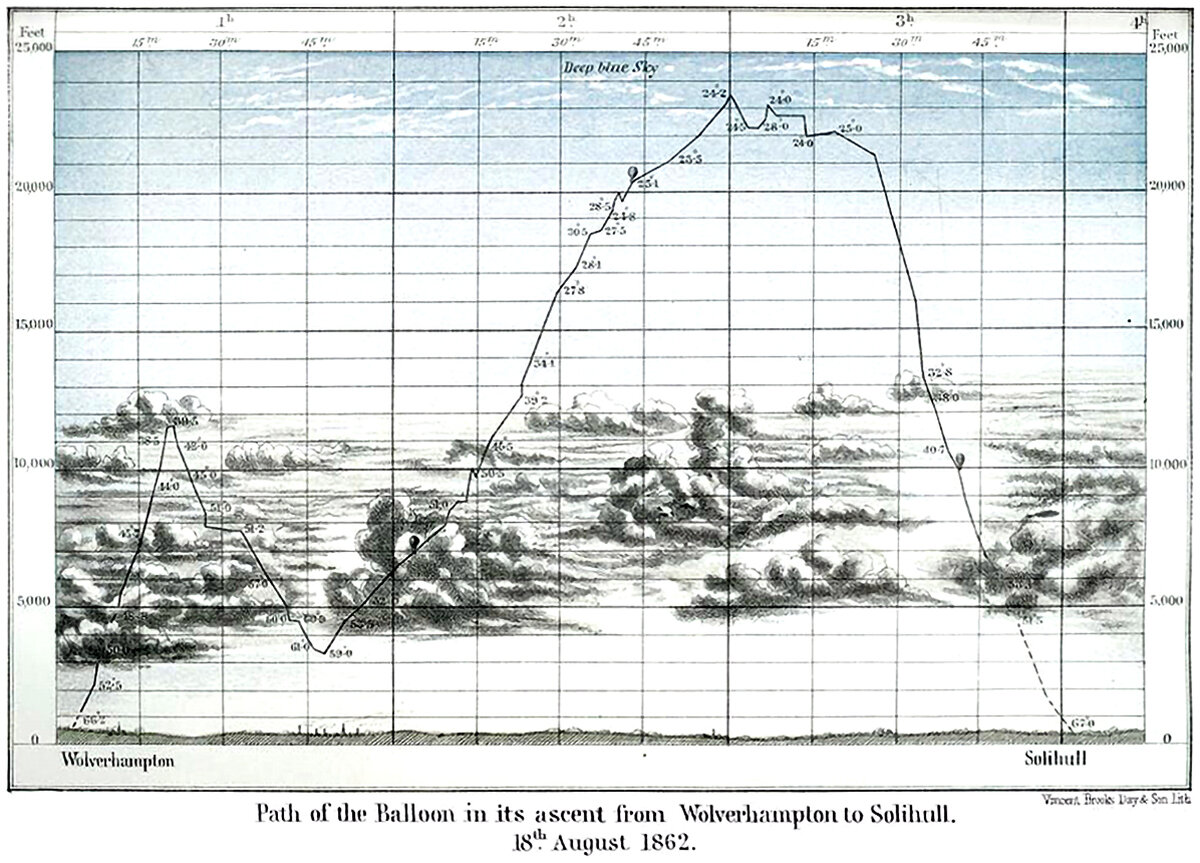

What Goes Up, Must Come Down

I love a drawing that tells a story. Here’s an illustration that does just that; it’s a diagram showing the flight path of James Glaisher’s balloon on 18 August 1862, which travelled between Wolverhampton and Solihull, just outside Birmingham in England. It’s essentially a graph that plots altitude over time, with some embellishments added for effect. The story being told is in the graph’s line, which ascends and descends just as the balloon did during its flight.

Markus Pernhart’s Großglockner Paintings

The above painting was created in 1871 by Austrian artist Markus Pernhart. It shows the peak of the Großglockner, or Grossglockner, which is the tallest mountain in Austria. It does a great job capturing the contrasting scales of human and mountain. If you look closely, there are two groups of mountaineers pictured atop each peak, dwarfed by the jagged forms of snow and rock. This puts the focus of the painting on the majestic beauty of the mountaintop, rather than the effort it took the mountaineers to reach it. In many ways, these mountaineers are meaningless when compared to the mountain itself. The Großglockner has been around for millennia, and will still be around long after this expedition is finished.

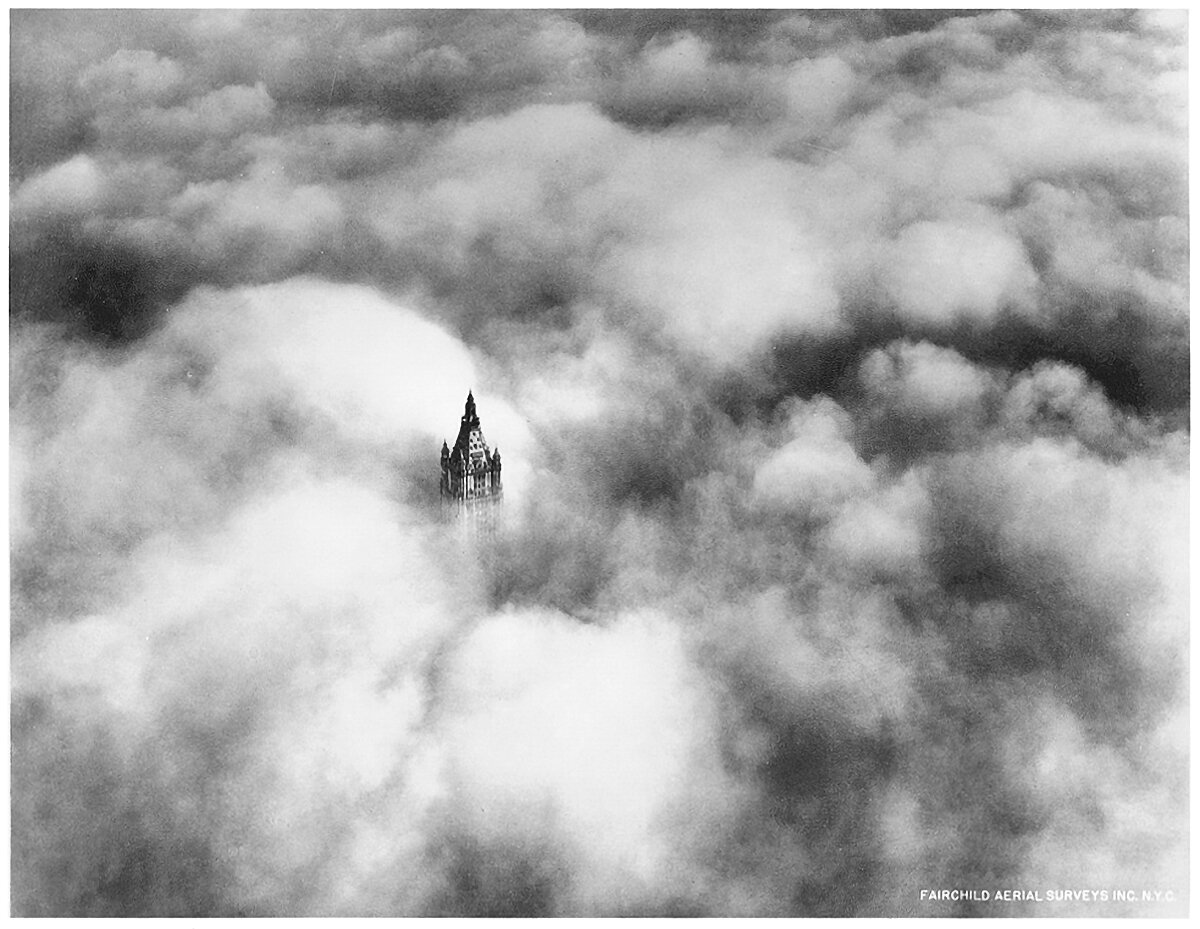

The Woolworth Building Tower Above the Clouds

The Woolworth Building was the tallest building in the world when it was completed in 1913. It towered above Lower Manhattan and dominated the skyline of the city. The above photograph was taken in 1928, and it shows the crown of the tower poking up through the clouds, inhabiting an otherworldly realm of sunlight and clouds. This is an iconic image, because it shows that buildings as tall as this achieve verticality for their occupants. On a day like this, the upper reaches of the building are truly in the sky.

Anecdotes : Earning the Summit

I recently had the opportunity to summit Mount Washington in New Hampshire, and the experience brought to light a few aspects of verticality for me. It’s the tallest peak in the Northeast US, famous for it’s erratic weather patterns. As such, it’s been commercialized with a cog railway, auto road, visitor center and museum in order to attract tourist dollars to the park. This makes for an interesting summit experience, which is quite different than a typical mountaintop. Put simply, this is a summit you don’t have to earn by climbing up to it.

“What is the use of climbing Mount Everest? It is of no use. What we get from this adventure is just sheer joy. And joy is, after all, the end of life.”

-George Mallory, English mountaineer, 1886-1924.

Altitudinal Zonation : Mountains and Verticality

The earth’s atmosphere is defined by vertical gradients. As one rises, the air thins out, humidity decreases, and temperatures drop. It’s why we get altitude sickness when we travel to high places, and it’s why the tops of very high mountains are snow-capped. These vertical gradients are defined by altitudinal zonation.

Anecdotes : Mountain Climbing and Verticality

I took the above photo on a recent hike up Mount Washington in the White Mountains of New Hampshire. I was at the Lake of the Clouds, which is a small pond near the summit. The ascent up the mountain brought me face-to-face with some of the most breath-taking and unforgiving landscapes I’ve ever experienced. It was an intensely personal experience, and I still find myself struggling for the words to describe my feelings throughout the climb. It also helped me to understand a few aspects of the human need for verticality, and I’ll explore them in the following paragraphs.

“This is the human paradox of altitude: that it both exalts the individual mind and erases it. Those who travel to mountain tops are half in love with themselves, and half in love with oblivion.”

-Robert Macfarlane, British author, born 1976