Forests and Verticality

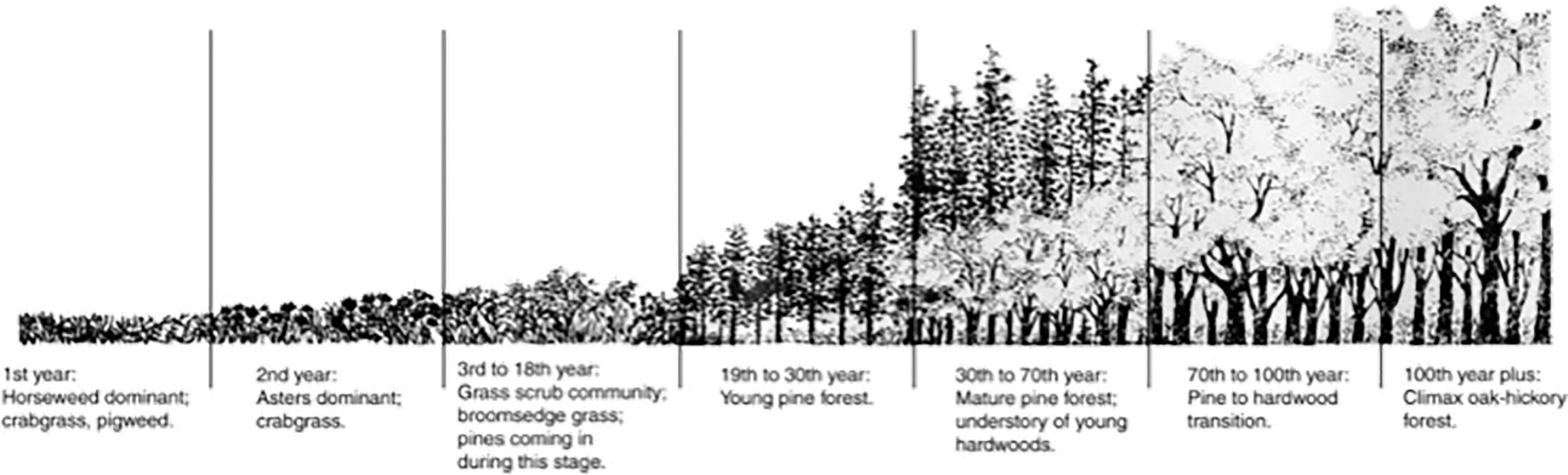

Piedmont Forest Succession from Duke University. Natural growth is based on verticality and follows a pattern that begins with small plants and progresses into massive hardwood forests.

The progression of forest growth over time is based on access to and competition for sunlight. This process is based on verticality. As a plant grows taller, it casts a shadow on everything below its foliage, hindering the growth of smaller plants below. This process can be found throughout the natural world, and it follows a pattern of regrowth called plant succession. Plant succession happens in one direction: up and away from the surface of the earth. Each individual plant has a goal to grow as tall as possible in order to maximize its chances for survival. In the aggregate, this functions like a race to the top, since the tallest plants have access to the most sunlight, and will therefore continue to grow as a result. This process is quite Darwinian, as Richard Dawkins explains:

’Why, for instance, are trees in forests so tall? The short answer is that all the other trees are tall, so no one tree can afford not to be. It would be overshadowed if it did. This is essentially the truth, but it offends the economically minded human. It seems so pointless, so wasteful. When all the trees are the full height of the canopy, all are approximately equally exposed to the sun, and none could afford to be any shorter. But if they were all shorter; if only there could be some sort of trade-union agreement to lower the recognized height of the canopy in forests, all the trees would benefit. They would be competing with each other in the canopy for exactly the same sunlight, but they would have ‘paid’ much smaller growing costs to get into the canopy. The total economy of the forest would benefit, and so would every individual tree. Unfortunately, natural selection doesn’t care about total economics, and it has no room for cartels and agreements. There has been an arms race in which forest trees became larger as the generations went by. At every stage of the arms race there was no intrinsic benefit in being tall for its own sake. At every stage of the arms race the only point in being tall was to be relatively taller than neighboring trees.’[1]

Different species of plants have different strategies for growing tall, and a rough overview of the progression can be seen in the image above, and described in detail in this article from Duke University.[2] What begins with small, herbaceous species at ground level will ultimately grow into a massive hardwood forest, and verticality is the driving force behind the growth.

[1]: Dawkins, Richard. The Blind Watchmaker. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1986. 261.

[2]: “Succession in the North Carolina Piedmont.” Duke Forest Teaching & Research Laboratory. Accessed September 6, 2019. https://dukeforest.duke.edu/forest-environment/forest-succession/.