Welcome to On Verticality. This blog explores the innate human need to escape the surface of the earth, and our struggles to do so throughout history. If you’re new here, a good place to start is the Theory of Verticality section or the Introduction to Verticality. If you want to receive updates on what’s new with the blog, you can use the Subscribe page to sign up. Thanks for visiting!

Click to filter posts by the three main subjects for the blog : Architecture, Flight and Mountains.

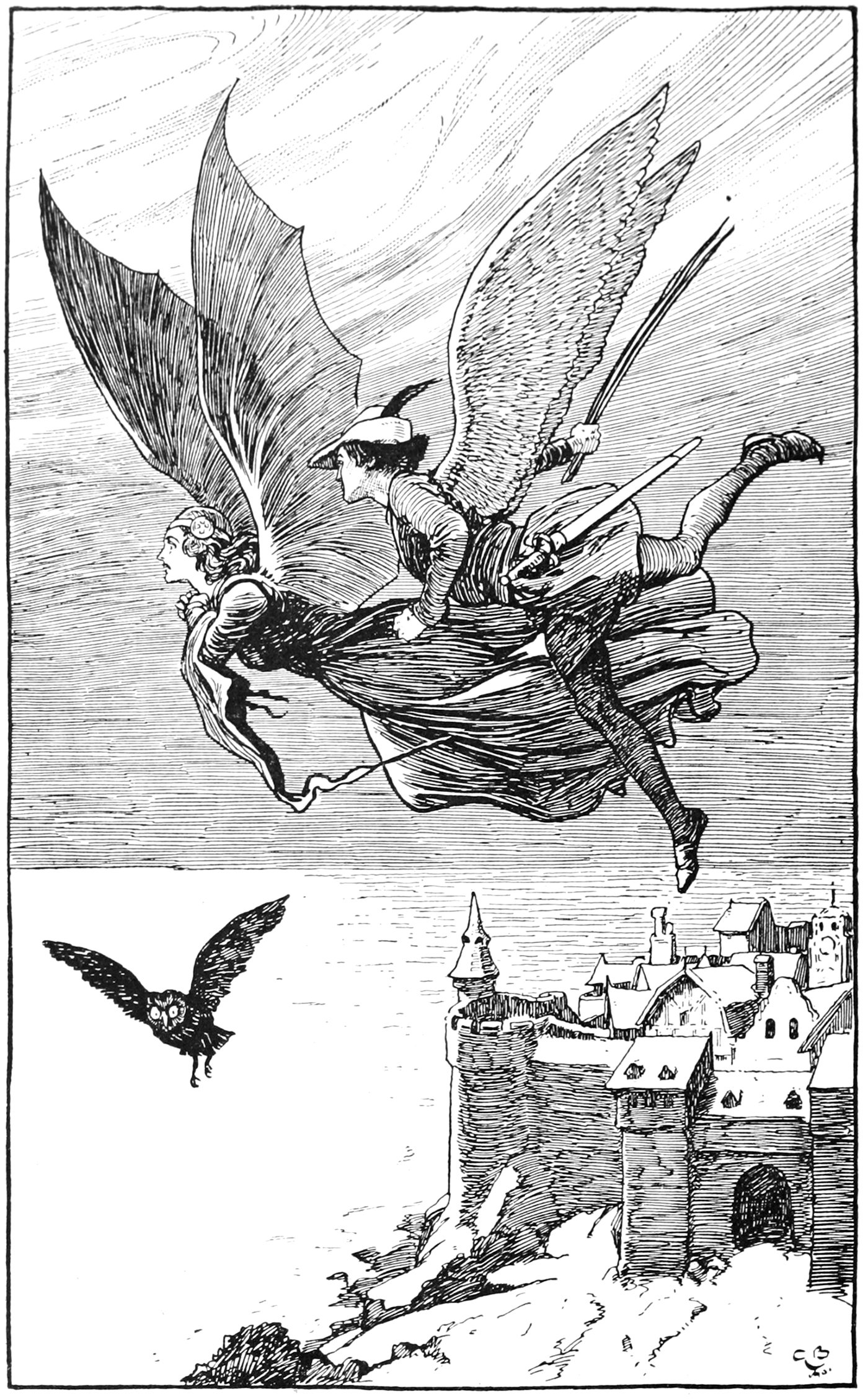

The Traveling Companion

The Traveling Companion is a fairy tale written by Hans Christian Andersen in 1835. It follows the travels of a man named John, and how he comes to marry a princess. Along the way, he meets a traveling companion who helps him in various situations, and one of his defining features is his ability to fly.

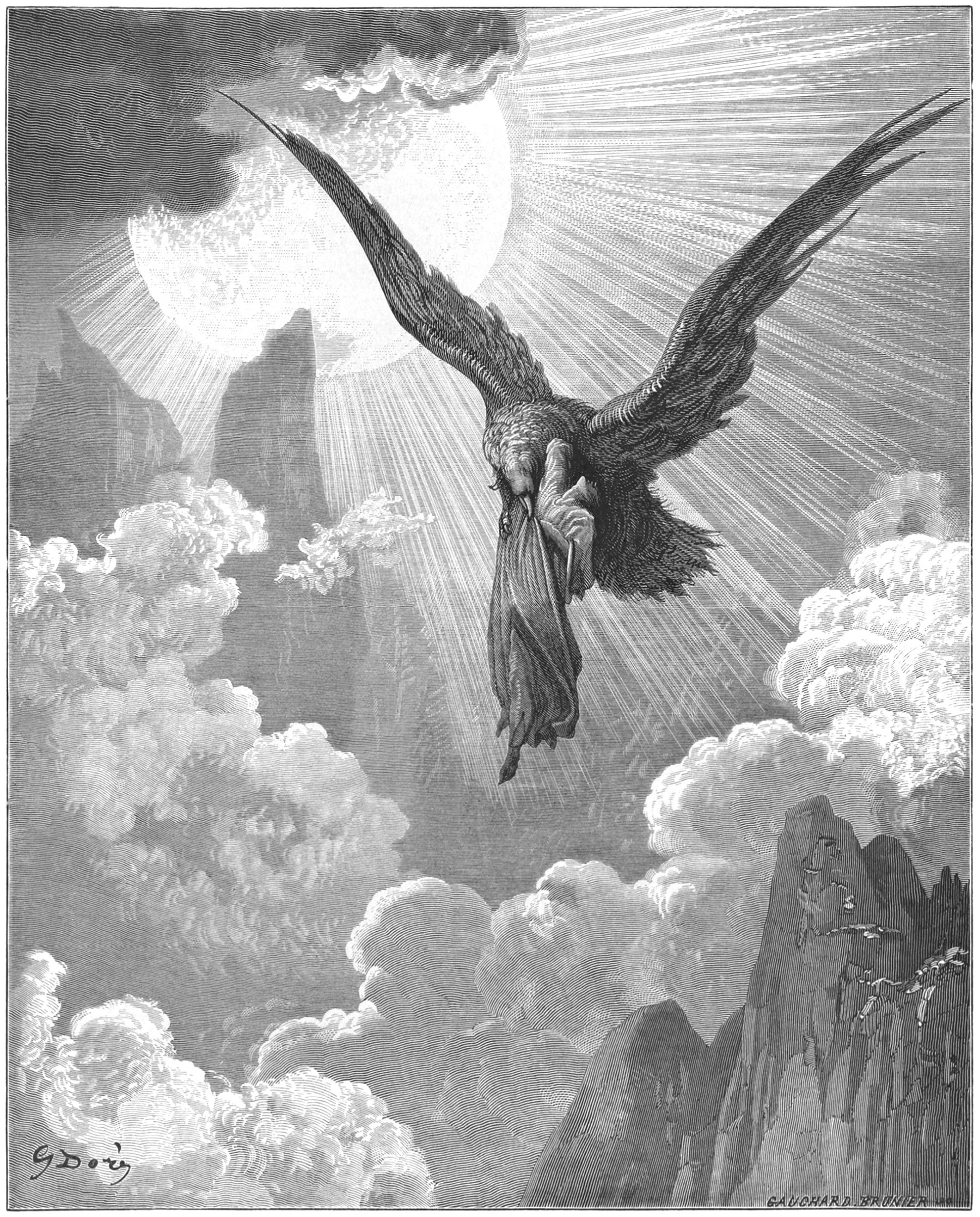

Dante and the Eagle

Pictured above is an illustration by Gustave Doré showing a scene from Dante’s Purgatorio. The scene takes place in Canto IX, as Dante is carried by an Eagle to the entry point of Purgatory. As I’ve previously written, the entire structure of Dante’s Divine Comedy is rooted in verticality, and this scene is just one example of this. Purgatory is a mountain which Dante must ascend in order to reach Paradise, or heaven.

Alexander the Great’s Flying Machine

The oldest myths and legends about human flight usually involve birds and other winged creatures that were already known to fly. These creatures were ready-made-packages of sorts. Harnessing their ability to fly by means of control provided the easiest and quickest path to human flight. Pictured above is one such example of this. It’s a mythical flying machine built by Alexander the Great.

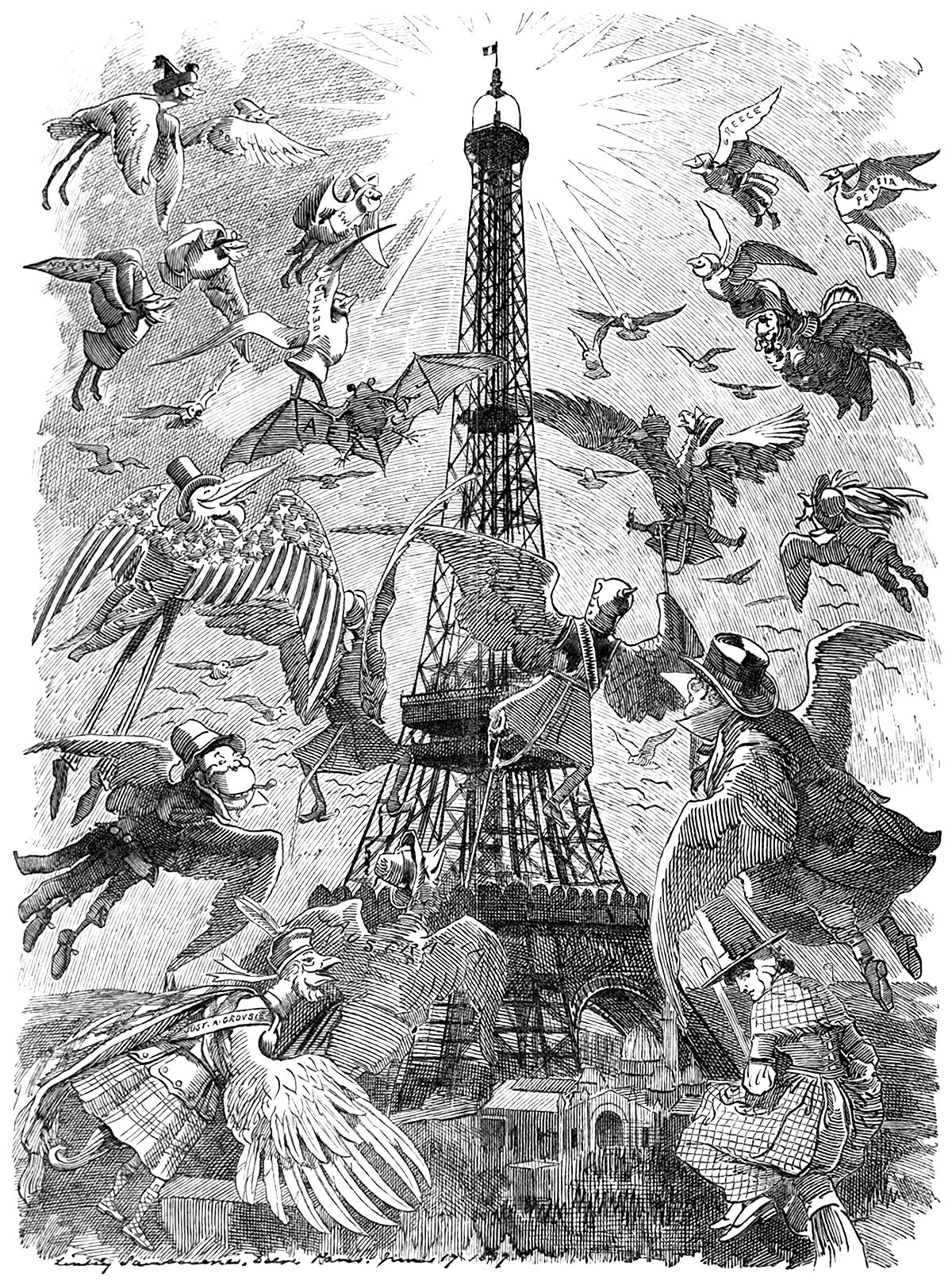

The Eiffel Tower Effect

When the Eiffel Tower was completed in 1889 for the World’s Fair in Paris, it changed the world. It re-defined what humans were capable of, and it gave the city of Paris an architectural icon that hasn’t faded with age. It was the tallest structure in the world, and it allowed its visitors to achieve verticality. As such, upon its completion the world took notice. Countless media sources reported on the structure, and it instantly took its place on the world stage. Pictured above is one such example of this. It’s an illustration from an 1889 issue of Punch magazine, and it shows a flock of birds flying toward the Eiffel Tower. These birds represent the countries of the world, and the piece was meant to symbolize the world’s envy for the iconic tower.

E.P. Frost’s Ornithopters

Pictured above is a photo of E.P. Frost’s second ornithopter prototype. It consisted of a large a pair of wings and a metal scaffold, and it was powered by an internal combustion engine. According to Frost, the machine successfully achieved liftoff under its own power in 1904. This wasn’t a sustained flight, however, but rather a jump or a hop.

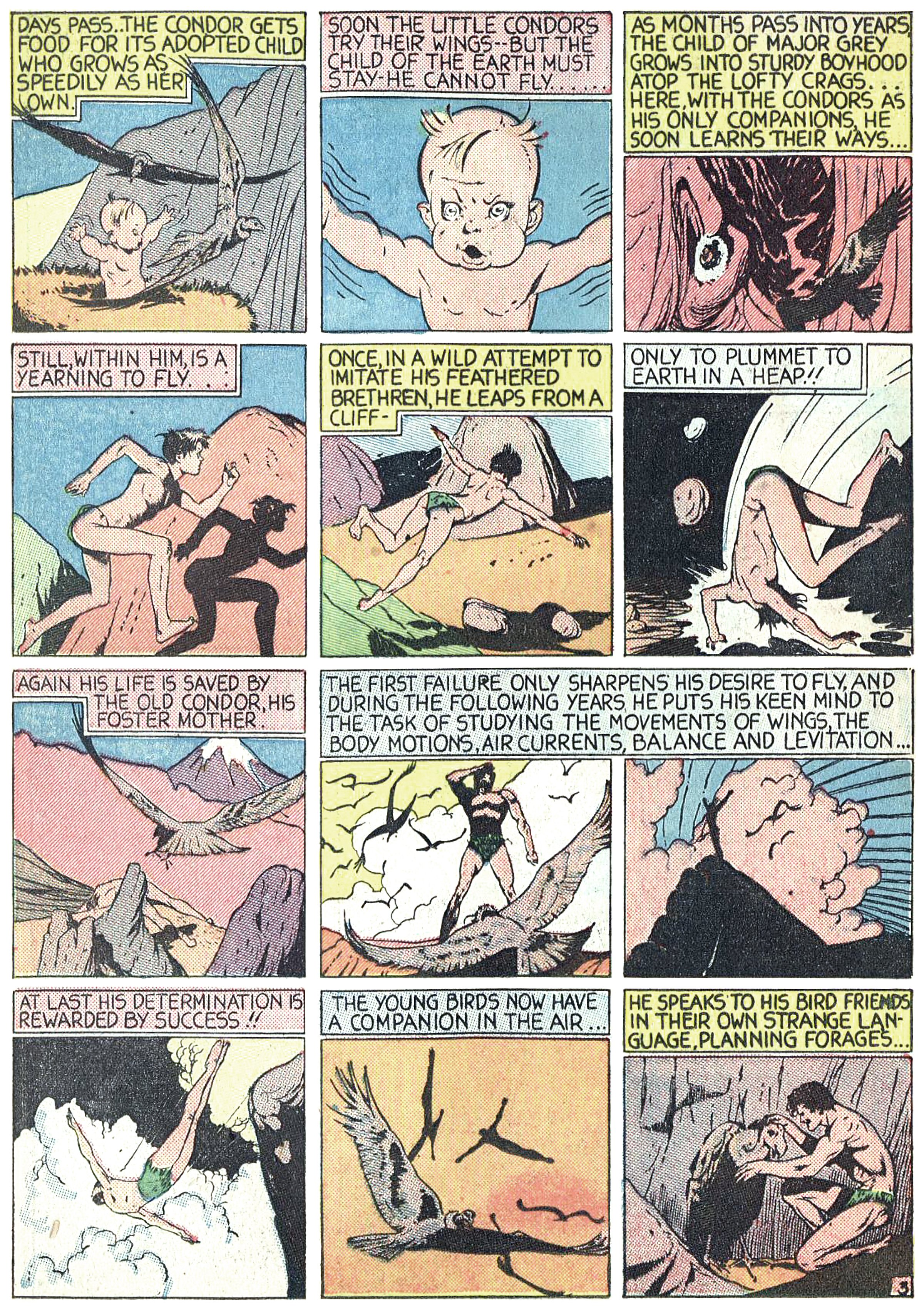

The Black Condor : The Man Who Can Fly Like A Bird

The first failure only sharpens his desire to fly, and during the following years, he puts his keen mind to the task of studying the movements of wings, the body motions, air currents, balance and levitation.

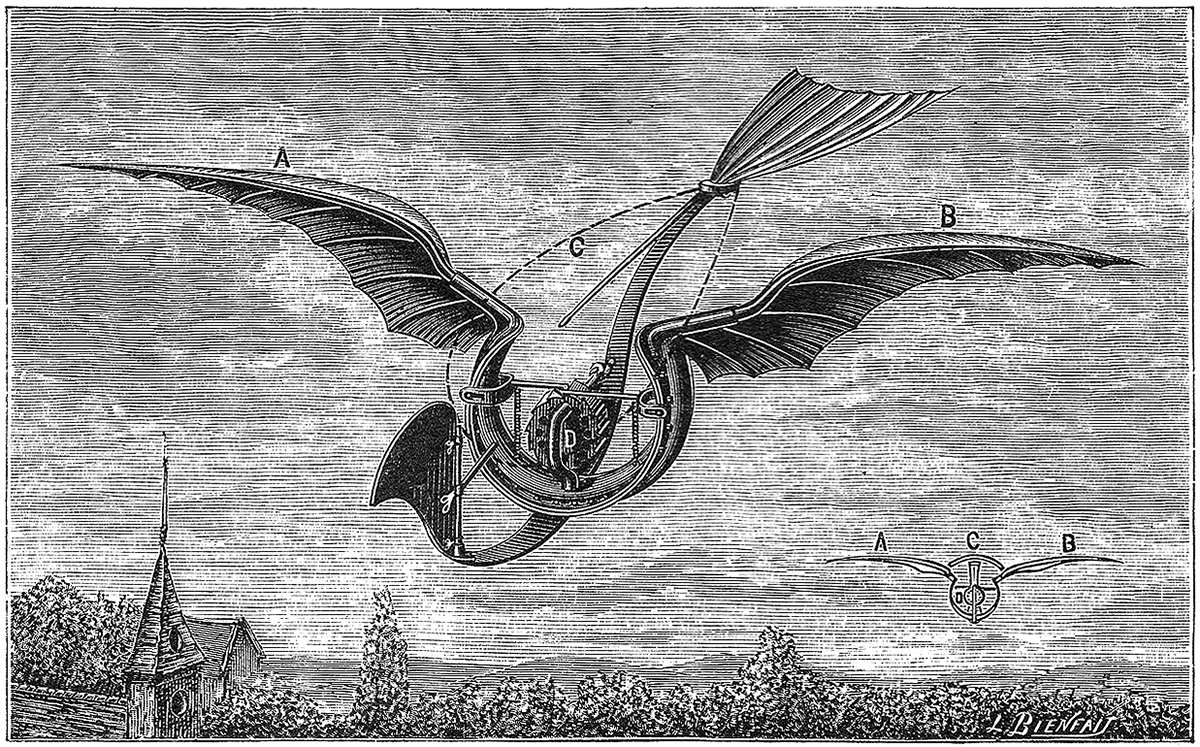

Gustave Trouvé’s Flügelflieger

Pictured above is an ornithopter design from 1891 by French polymath and inventor Gustave Trouvé. It was called the Flügelflieger, which means winged flyer in German. It featured a pair of wings, a tail, a front rudder, and it was powered by a centrally-placed rapid-succession gun cartridge. Due to the gunpowder charges, the machine was quite loud when flapping. It did work though; according to Trouvé it made a successful flight of 80 meters (262 feet) on 24 August 1891.

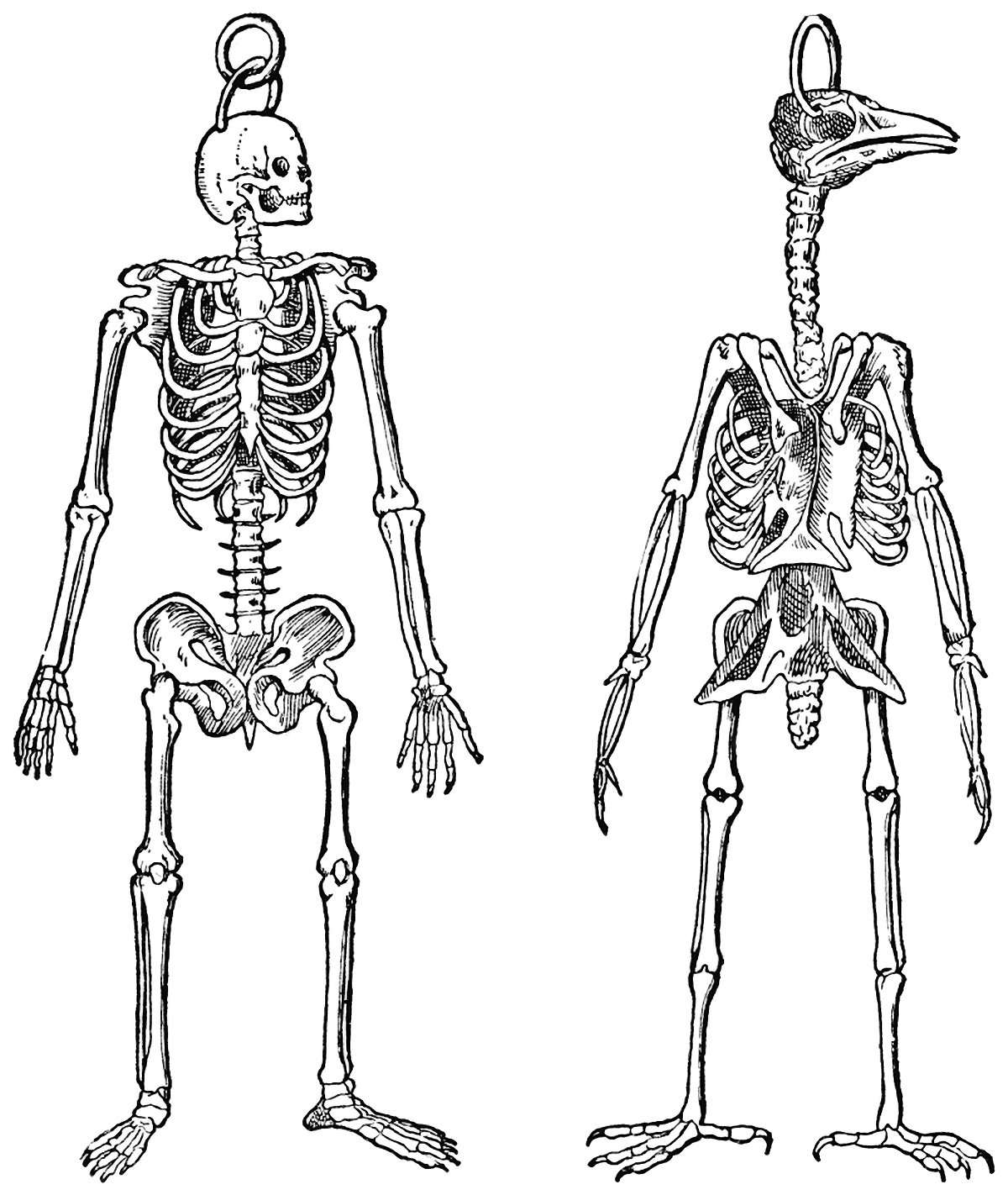

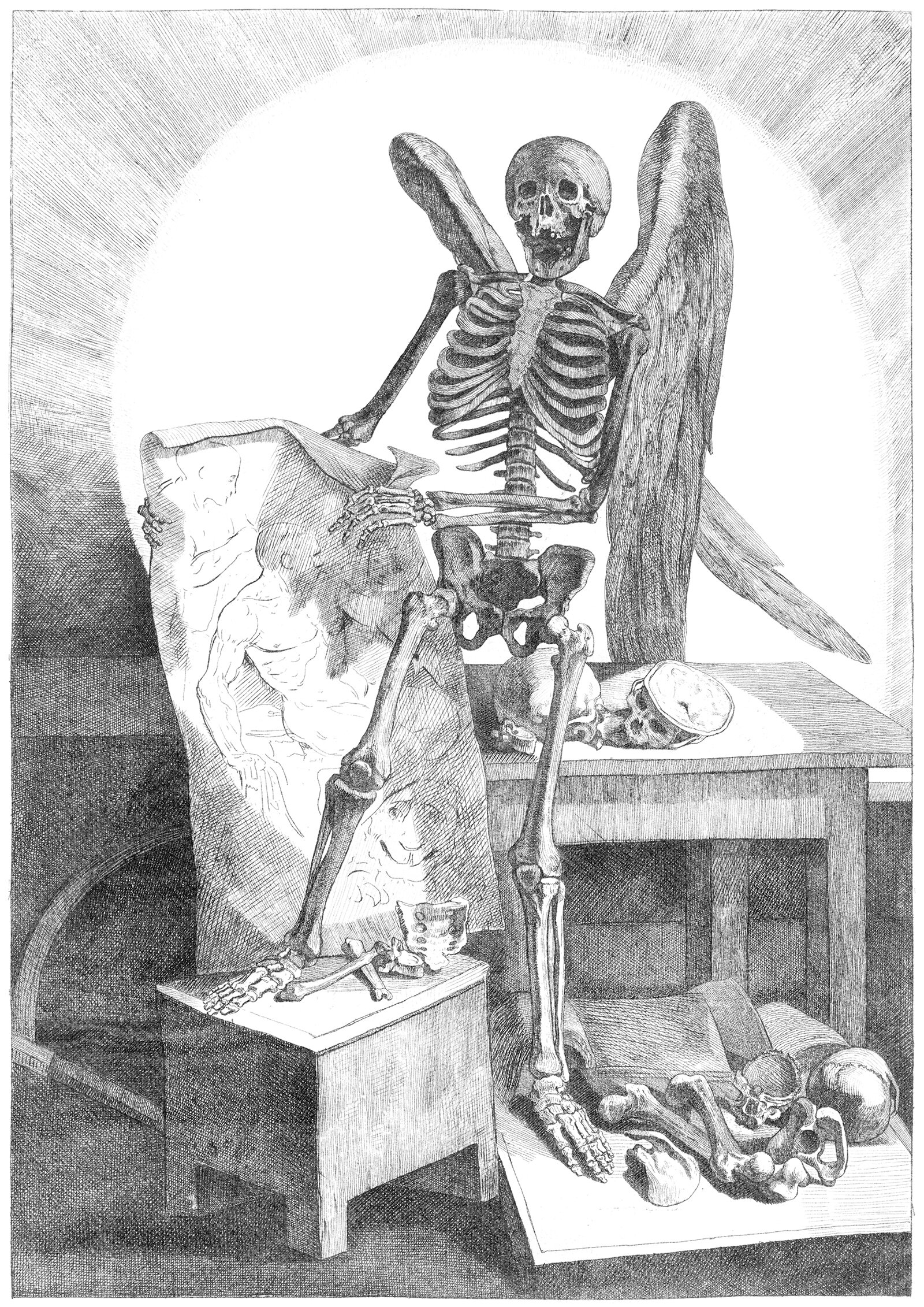

The Skeletons of a Man and Bird

Pictured above is a comparison between the skeleton of a human and a bird. What I find fascinating about this image is the choice of the artist to position the bird in a bipedal stance. I suspect this was done just to ease the comparison, but in a way it undermines the birds power of flight. This is an animal who is at home when in the open air, but here the bird is shown with its feet firmly planted on the ground, much like a human. The playing field has been leveled, so to speak, which puts the bird at a specific disadvantage.

Peter Pan and the Delights of Flying

Peter Pan is perhaps best known from the animated 1953 film Peter Pan, but his story originated in the book Peter and Wendy, written in 1911 by J. M. Barrie. It’s a story of fairies, mermaids, pirates, and a mischievous boy with the power of flight. This boy, named Peter Pan, has adventures in Neverland with a group of British children that he teaches to fly. Flight is central to the narrative of the story, and Barrie does a good job of describing the children’s joy as they learn to fly.

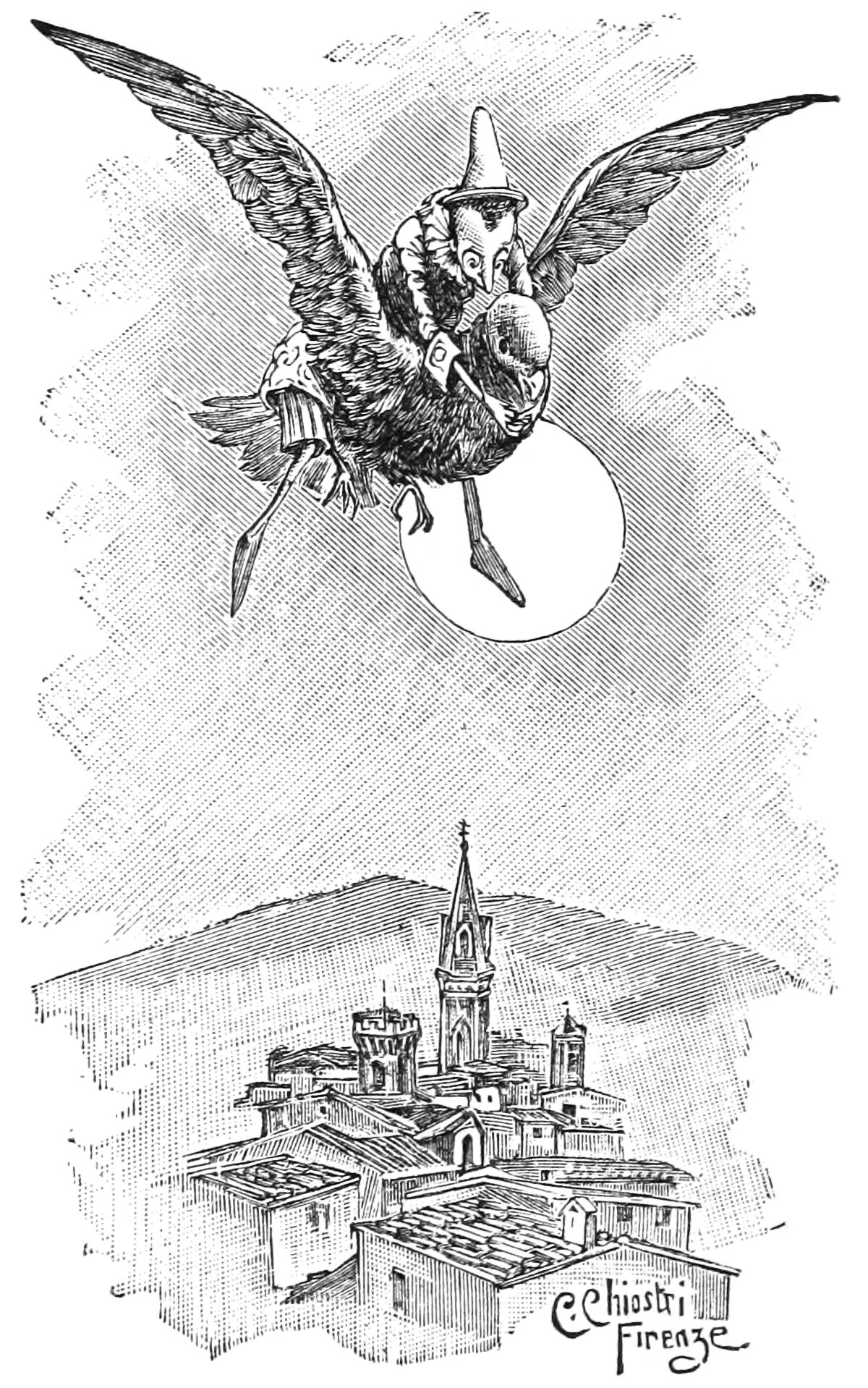

Pinocchio’s Feathered Steed

Folklore and fantasy are full of references to the power of flight. These references usually take one of two different forms. The first are characters who can actually fly, and the second are characters who fly by means of another creature. Examples of the first are fairies, angels, cherubs, and seraphs, among many others. The illustration above shows an example of the second. It’s from Carlo Collodi’s 1883 children’s book The Adventures of Pinocchio, when the titular character hitches a ride on the back of a giant pigeon.

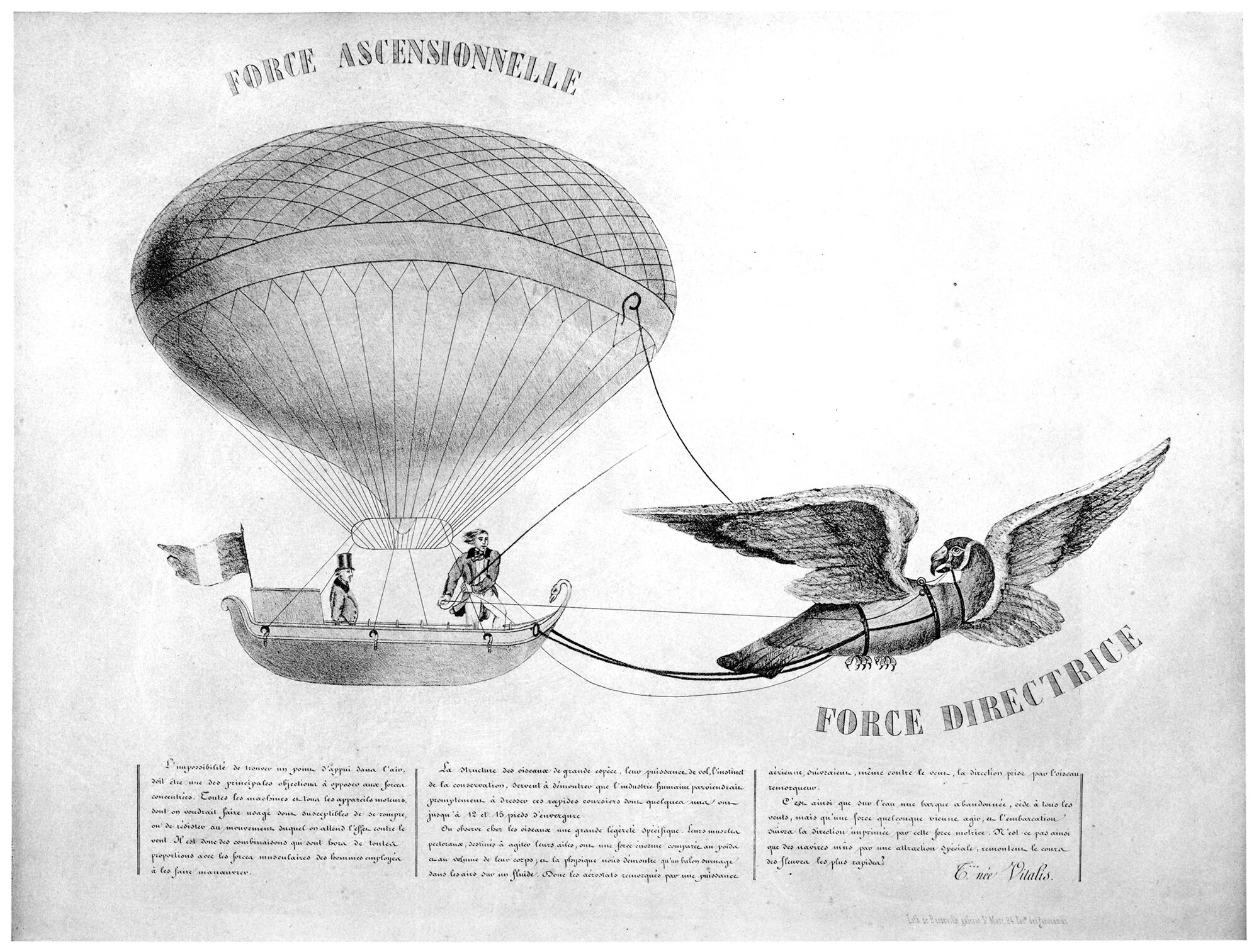

Tessiore’s Balloon Project Towed by a Tame Vulture

Pictured above is a design for a flying machine, consisting of a balloon pulled by a tame vulture. It was originally published in 1845, and was re-published in 1922 in the book L’Aeronautique des origines a 1922. The title of the illustration is Projet de Ballon Remorqué par un Gypaète Spprivoisé, or Project for a Balloon Towed by a Tame Vulture. I’m unable to find any data on the image apart from this, but the content itself is enough to discuss, for obvious reasons.

The Human Body and Flight : Why We Can’t Fly

The ability to fly is something that’s been on the human mind since time immemorial. We see birds and other creatures flying through the air, and we seek to fly as they do. We dream about it, and we’ve thought up myriad examples of human-like characters throughout our legends and myths who can fly. For all our hoping, however, it’s impossible for us to fly under our own strength. Let’s take a closer look at why this is true.

Abbas ibn Firnas’ Attempt At Flight

Abbas ibn Firnas, also known as Armen Firman, was an Andalusin polymath best known for an attempt at flight around 875 AD. Details are scarce, but Firnas allegedly built a pair of wings and jumped from a tower somewhere in Córdoba. His wings allowed him to glide for a bit before crash-landing and injuring his back.

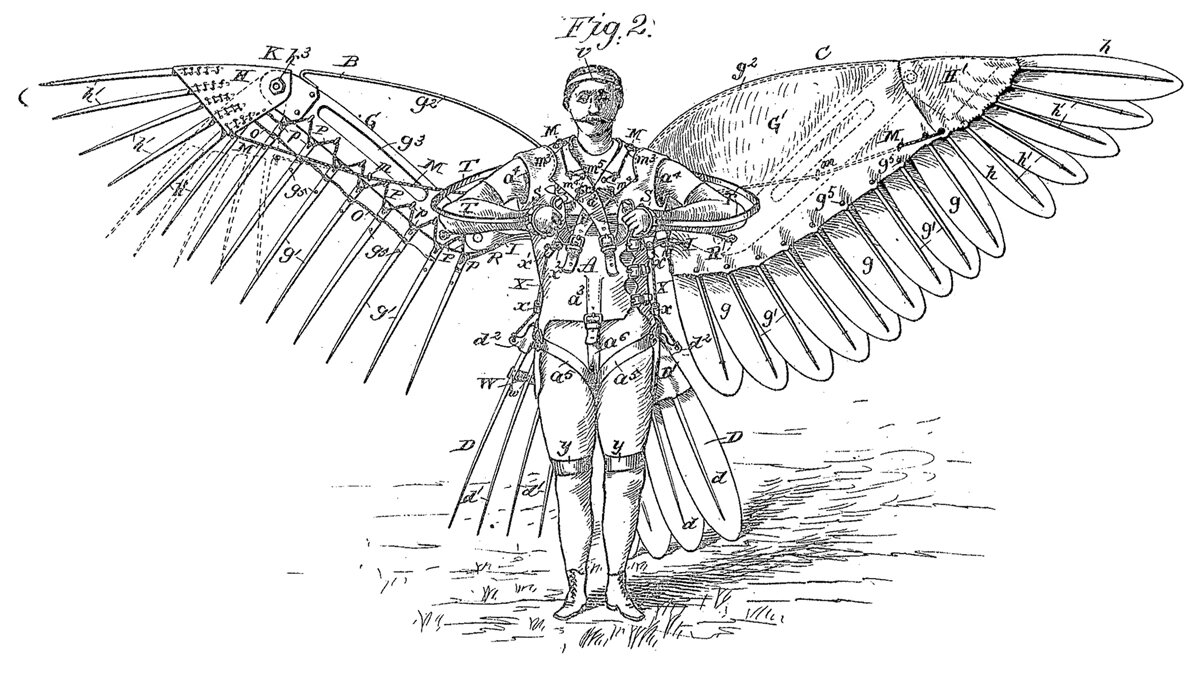

R.J. Spalding’s Birdman Suit

This is Reuben Jasper Spalding’s design for a flying machine, which he successfully patented in 1889. The design is so on-the-nose, I haven’t made up my mind whether it’s amazing or absurd. There’s a chance it’s an honest attempt at human flight, but I see it more as an homage to the earliest flying machines, which took the myth of Daedalus and Icarus and ran with it.

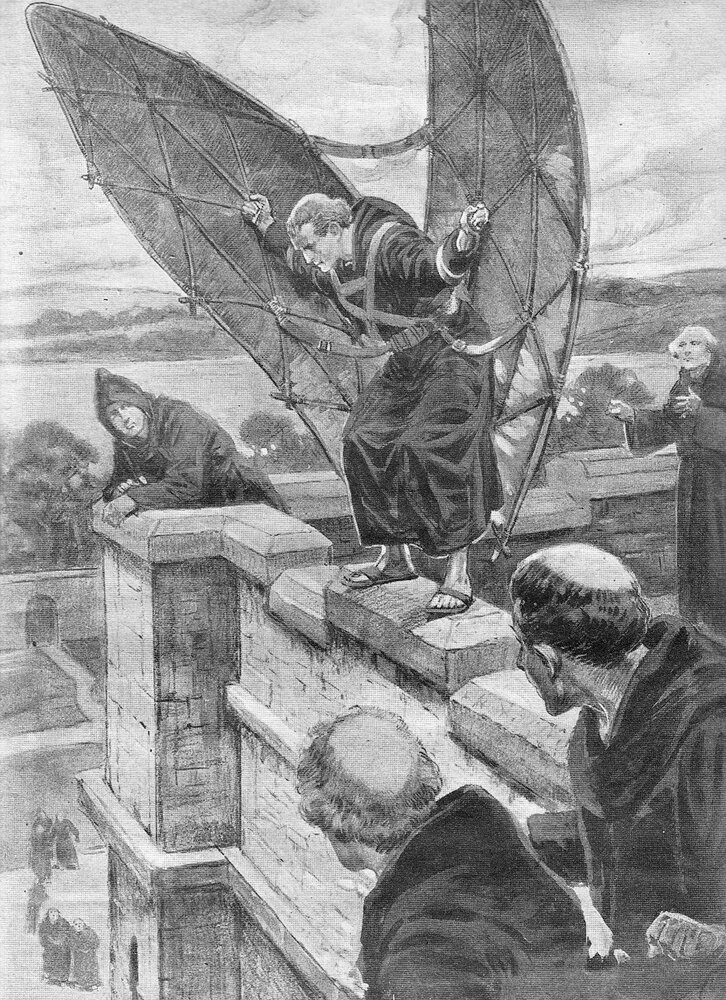

John Damian de Falcuis, the False Friar of Tongland

Pictured above is John Damian, an Italian alchemist best known for an attempt at human flight in 1507. At the time, Damian had been employed by King James IV as an alchemist, and his job was to create gold from more common materials. After he failed to do so and word got around that he was a fraud, he declared he would fly to France with a pair of wings he invented in an attempt to prove his critics wrong,

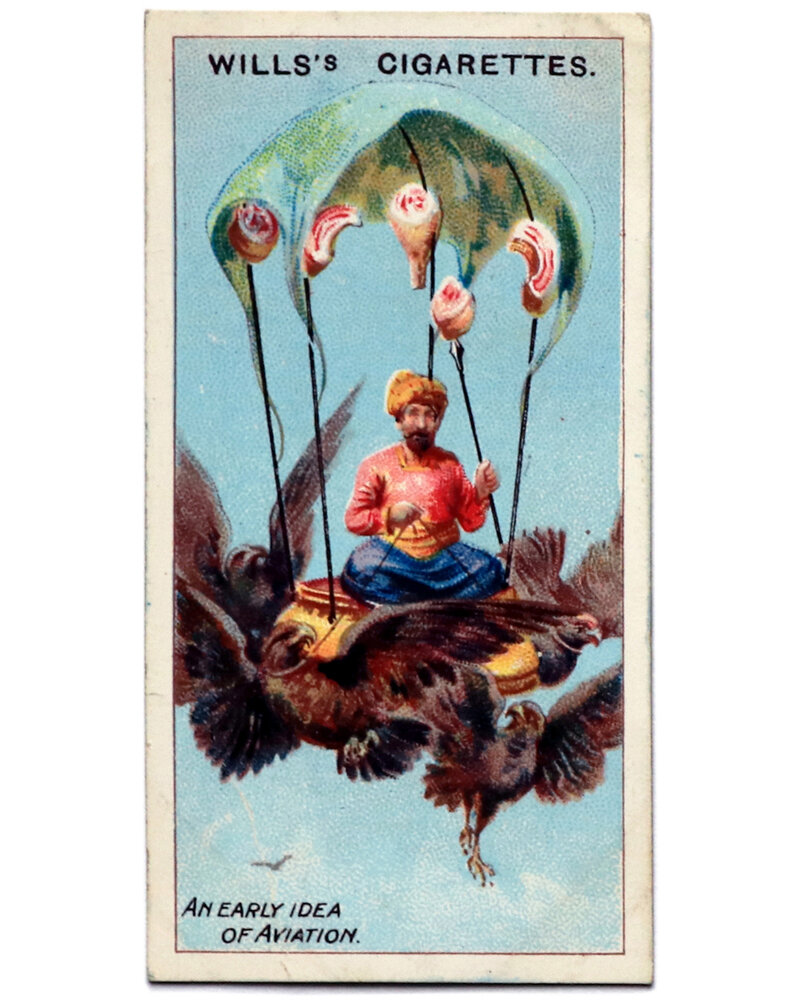

The Flying Throne of Kay Kāvus

The oldest examples of flying machines were the stuff of legends and fairy tales, and the most intriguing ones have endured over time. Pictured above is an illustration of one such tale, showing Kay Kāvus, a mythological Iranian King, and his flying throne. Kāvus was a character from the epic poem Shāhnāmeh, or Book of Kings, which was written circa 975-1010AD by the Persian poet Abul-Qâsem Ferdowsi.

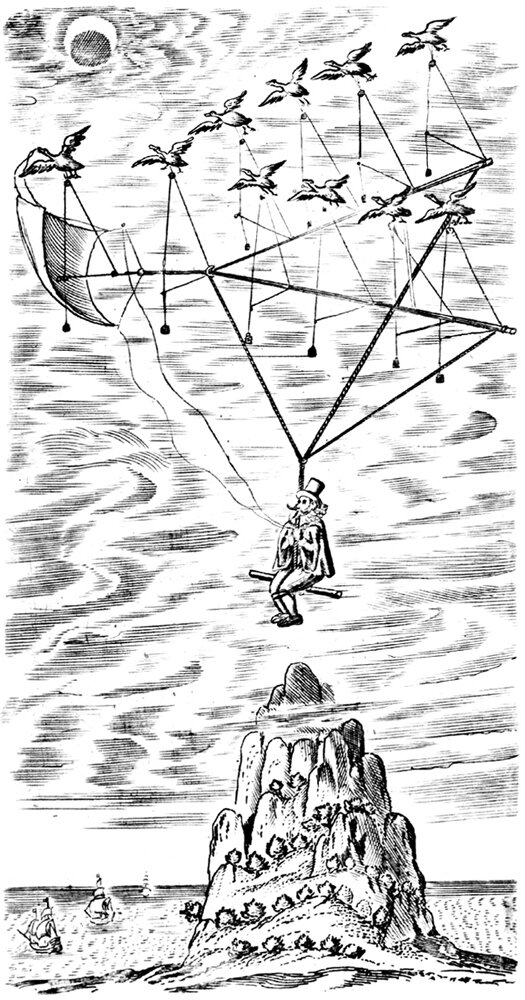

The Man in the Moone

Pictured here is the frontispiece to Francis Godwin’s 1657 book The Man in the Moone. The story is an adventure tale about Domingo Gonsales, a Spaniard who builds a flying machine while stranded on an island. The machine is powered by a flock of large swans, held together by a wooden skeleton with a simple seat at the base for Domingo to sit. From this simple perch, Domingo flies to the Moon and back, among other travels throughout the story.

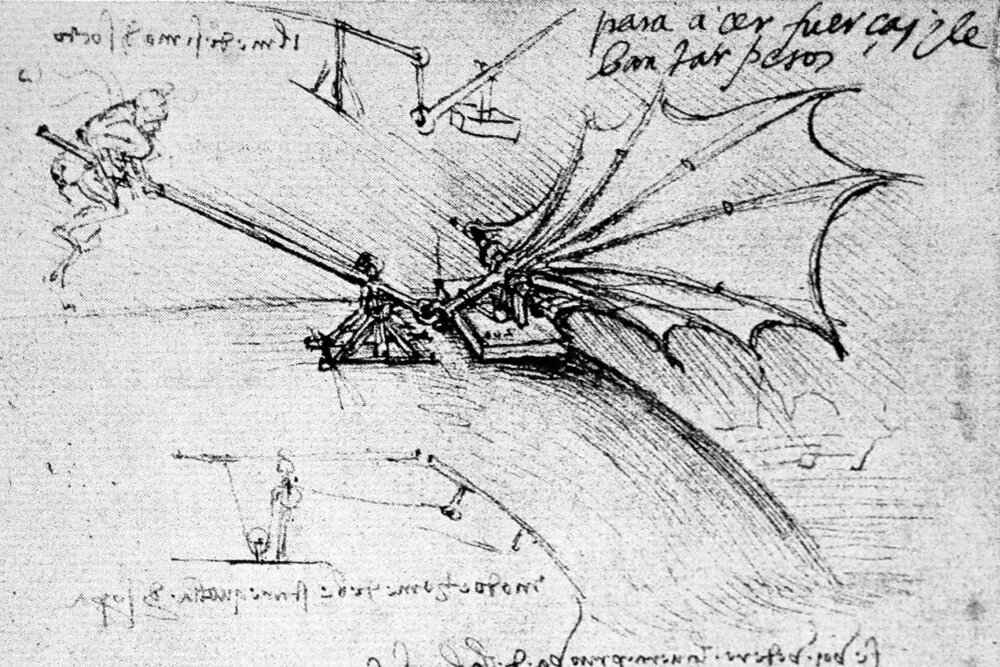

Leonardo da Vinci and Human Flight

Leonardo da Vinci is one of the most influential and prolific thinkers in human history. He is most famous for his paintings, but the man was a true polymath, and he studied and thought about myriad subjects. There is an obsessive curiosity that surrounds his oeuvre, and there doesn’t seem to be a limit to what he would explore. For our purposes here, we’ll focus on his quest for human flight, which he pursued from the late 1480’s to the mid 1490’s.

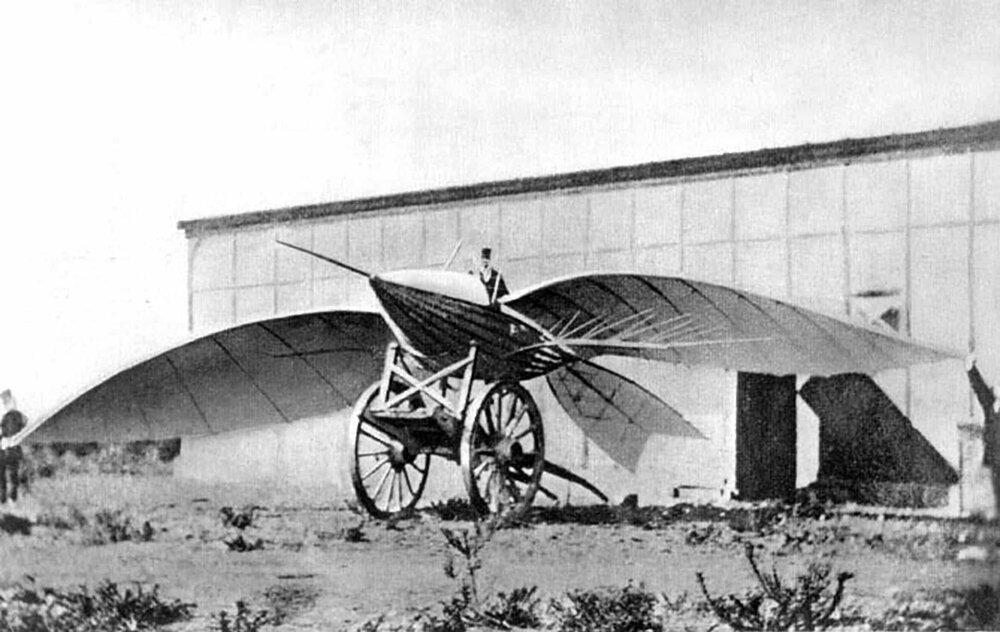

Jean-Marie Le Bris' Artificial Albatross

Pictured above is a photograph of Jean-Marie Le Bris’ flying machine, called L'Albatros artificiel, which is French for Artificial Albatross. This is the first recorded photograph taken of a flying machine, and it shows Le Bris in the pilot seat of his glider, resting on a wooden cart before take off. This is the second version of his craft, called Albatross II, which was modified from the original version with refinements.

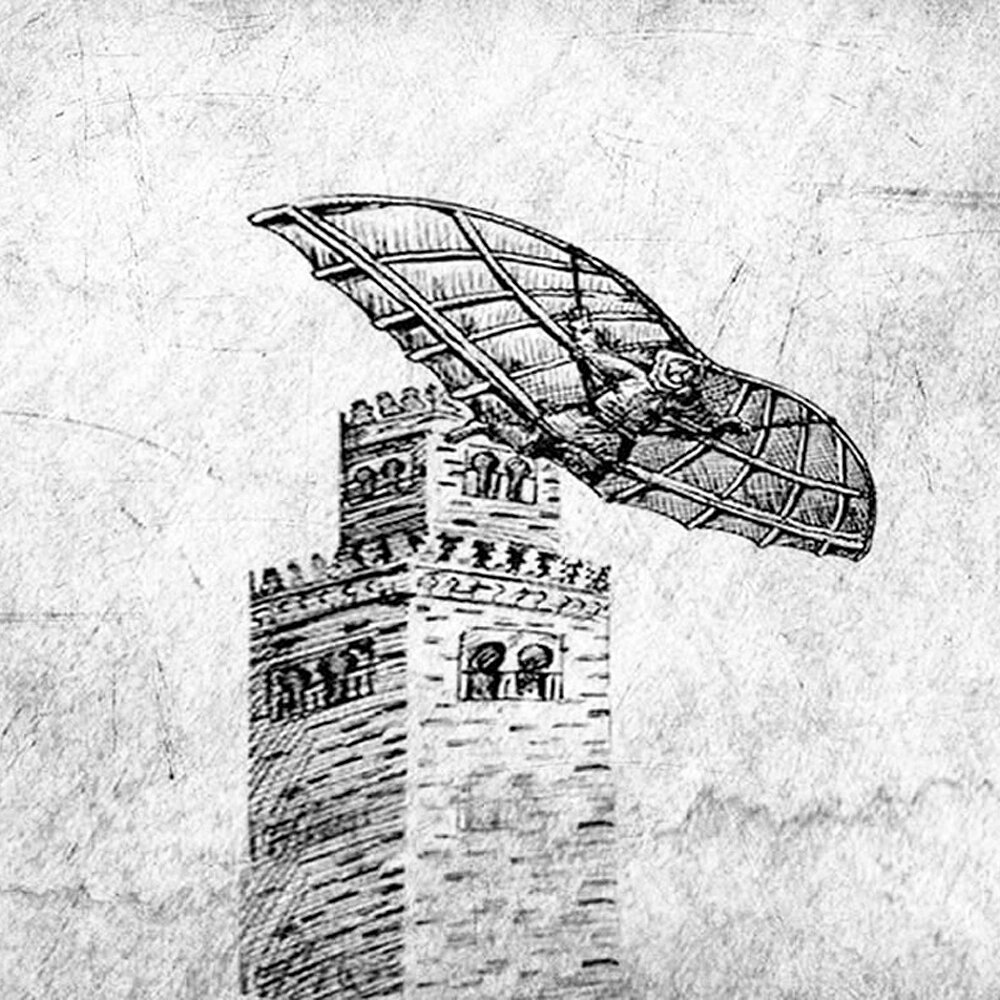

Eilmer of Malmesbury, The Flying Monk

Pictured above is Eilmer of Malmesbury, an English Benedictine monk who lived sometime in the early 11th century. He is best known for an alleged attempt at human flight, which marks one of the earliest recorded attempts of its kind. Unfortunately, the details of his life have been lost to time, except for a single passage in William of Malmesbury's book Gesta Regum Anglorum. William describes Eilmer as a bold youngster who, inspired by the Greek myth of Daedalus and Icarus, believed he could fly by constructing a pair of wings and attaching them to his hands and feet.