The Verticality of Clouds

I recently climbed Mount Saint Helens in Washington state, and the experience brought me face-to-face with the verticality of clouds. The photo above was taken just after dawn, and you can see two very different types of clouds in the sky. Just above my head was a dense, thin layer of stratus clouds, which looked solid and dark from below. Far above this was a wispy pattern of cirrus clouds, which was much lighter in appearance. In addition to these, there were also groups of low-lying stratus clouds in the valleys below. What struck me in that moment was each of these cloud types was created by the exact same elements, the only difference was their height above the surface.

As air rises through the atmosphere, two things happen. First, it gets colder. This drop in temperature results in lower air density, which is why it’s harder to breathe at higher altitudes. Second, the thinner air can’t hold as much moisture without condensing. As the temperature drops, the moisture in the air will eventually reach the dew point, and it will condense into water droplets. This is why we can see our breath when it’s cold outside. The warm air from our lungs cools rapidly as we breathe out, and it quickly reaches its dew point and condenses into visible water droplets. At a much larger scale, this same process creates clouds.

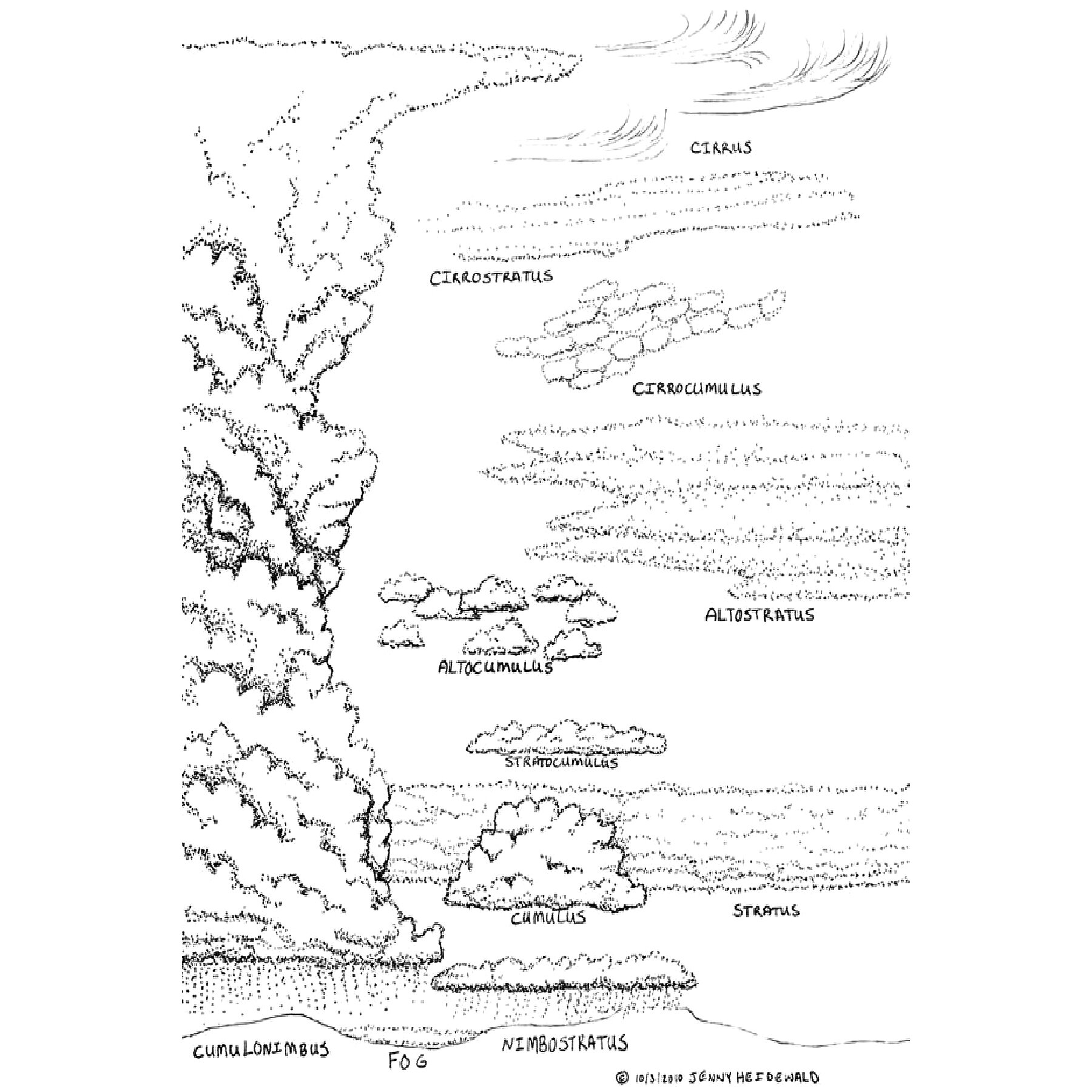

Clouds are generally classified by their height and shape, and their names are formed by combining a few Latin roots. First there are two height-based roots. The first is cirro-, meaning curl of hair, which are the highest clouds. The second is alto-, meaning high, which are mid-level clouds. Next, there are two formation-based roots. The first is strato-, meaning bed, which are layered clouds that form horizontally. The second is cumulo-, meaning heap or pile, which are puffy clouds that form vertically. A fifth root is nimbo-, which means rain or precipitation.

There are three vertical zones in which clouds form. At the highest zone, we have the cirro- clouds. These clouds are formed by ice crystals, and they’re generally light and white in appearance. The three types of high-level clouds are cirrus, cirrostratus, and cirrocumulus. Cirrus clouds are light and feathery, much like the photo at the top of the page. Cirrostratus are more widespread and tend to form a white layer over large parts of the sky. Cirrocumulus are smaller, puffy clouds that tend to follow loose patterns across the sky. These high-level clouds can signal upcoming changes to the weather, but they rarely affect current weather conditions on the ground.

At the mid-level zone, we have the alto- clouds. Depending on specific conditions, these clouds can be formed by ice crystals, water droplets, or a combination of the two. They can either rise up to become cirro- clouds, or lower down to become de-alto-ed versions of themselves (there’s no prefix for low-level clouds). The two types are altostratus and altocumulus. Altostratus clouds, like the layer in the photo above, form in a horizontal layer, while altocumulus form vertically, and appear similar to cirrocumulus clouds.

At the low-level zone, we have non-prefixed cloud types and clouds that produce rain and snow. The two main types are stratus and cumulus. Both are similar to their higher-altitude counterparts, but they are more dense and they can produce precipitation. If they do so, they are called nimbostratus and cumulonimbus, respectively. These two types of clouds directly affect weather conditions at the surface, and they’re the main culprits behind precipitation and storms.

Pictured here is another example of different cloud layers. There’s a mid-level of cumulus clouds that appear light and fluffy, with a backdrop of cirrostratus clouds that cover the entire sky, rendering it white.

I always find it fascinating how the world above our heads can seem abstract and far-away, but while climbing a mountain the layers and depth begin to come into focus. As I climbed Mount Saint Helens, I ascended past the thin layer of stratus clouds, but the cirrus clouds remained high above me, even at the crater rim. Had I remained down below, I wouldn’t have interacted with the clouds like I did once I was on the upper mountain. As I ascended into the atmosphere, I was able to be among the clouds, rather than below them.