Welcome to On Verticality. This blog explores the innate human need to escape the surface of the earth, and our struggles to do so throughout history. If you’re new here, a good place to start is the Theory of Verticality section or the Introduction to Verticality. If you want to receive updates on what’s new with the blog, you can use the Subscribe page to sign up. Thanks for visiting!

Click to filter posts by the three main subjects for the blog : Architecture, Flight and Mountains.

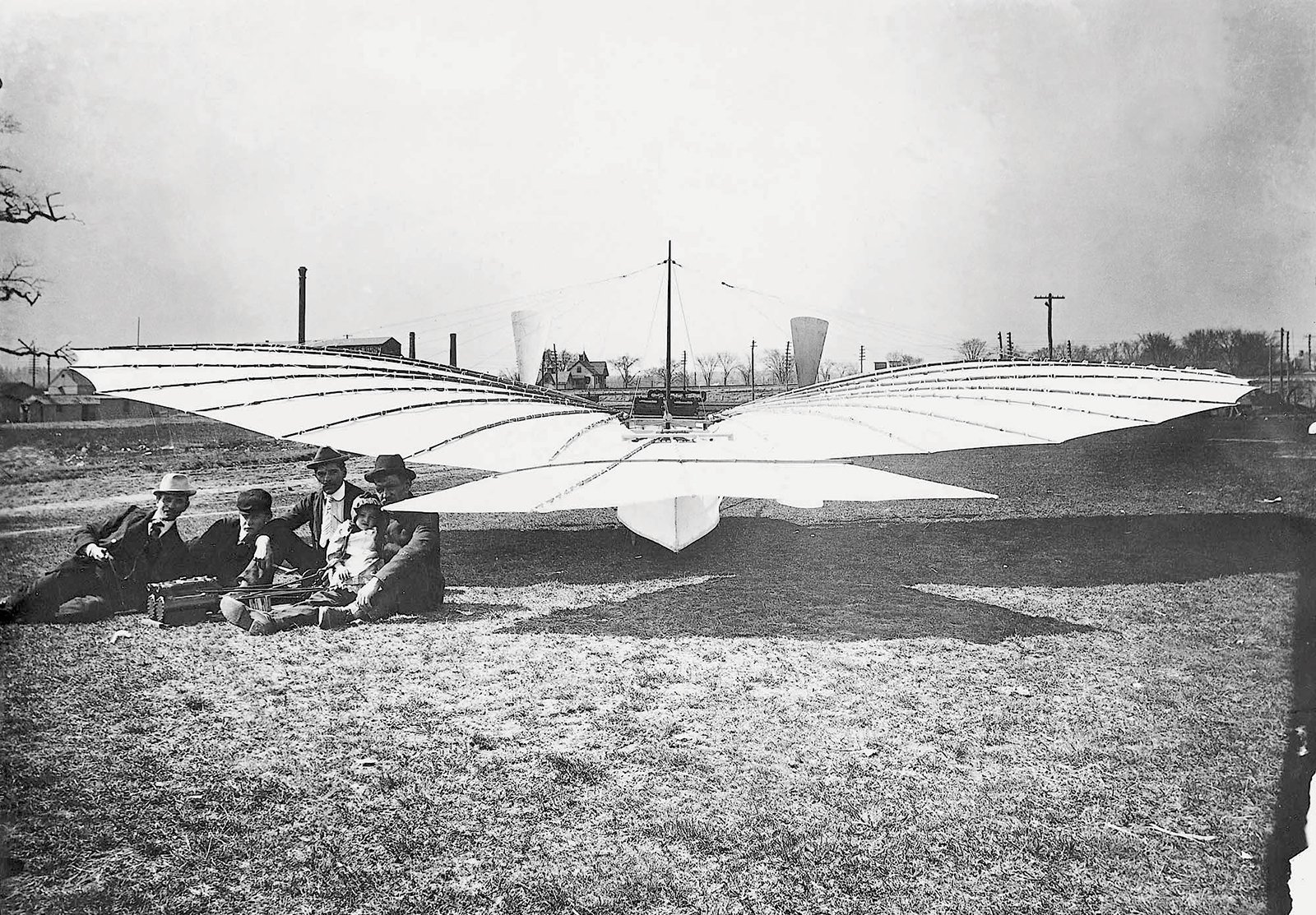

Augustus Moore Herring’s Gliders

In the field of early aviation, there are standout figures, such as the Wright Brothers or Otto Lilienthal. There’s also figures that work to push the field forward, and exist with and among other greats. Augustus Moore Herring is one such individual. Throughout his career as an aviation pioneer, his story is woven into the careers of many other pioneers of flight, while unfortunately remaining much less well-known.

Madame Helene Alberti’s Cosmic Wings

Pictured here are two photographs from 1931 showing a winged glider designed by Madame Helene Alberti. Alberti was a well-known opera singer who studied human flight after retiring from the opera. She believed in the Ancient Greek laws of cosmic motion, and believed humans can fly by their own strength after learning to use these laws.

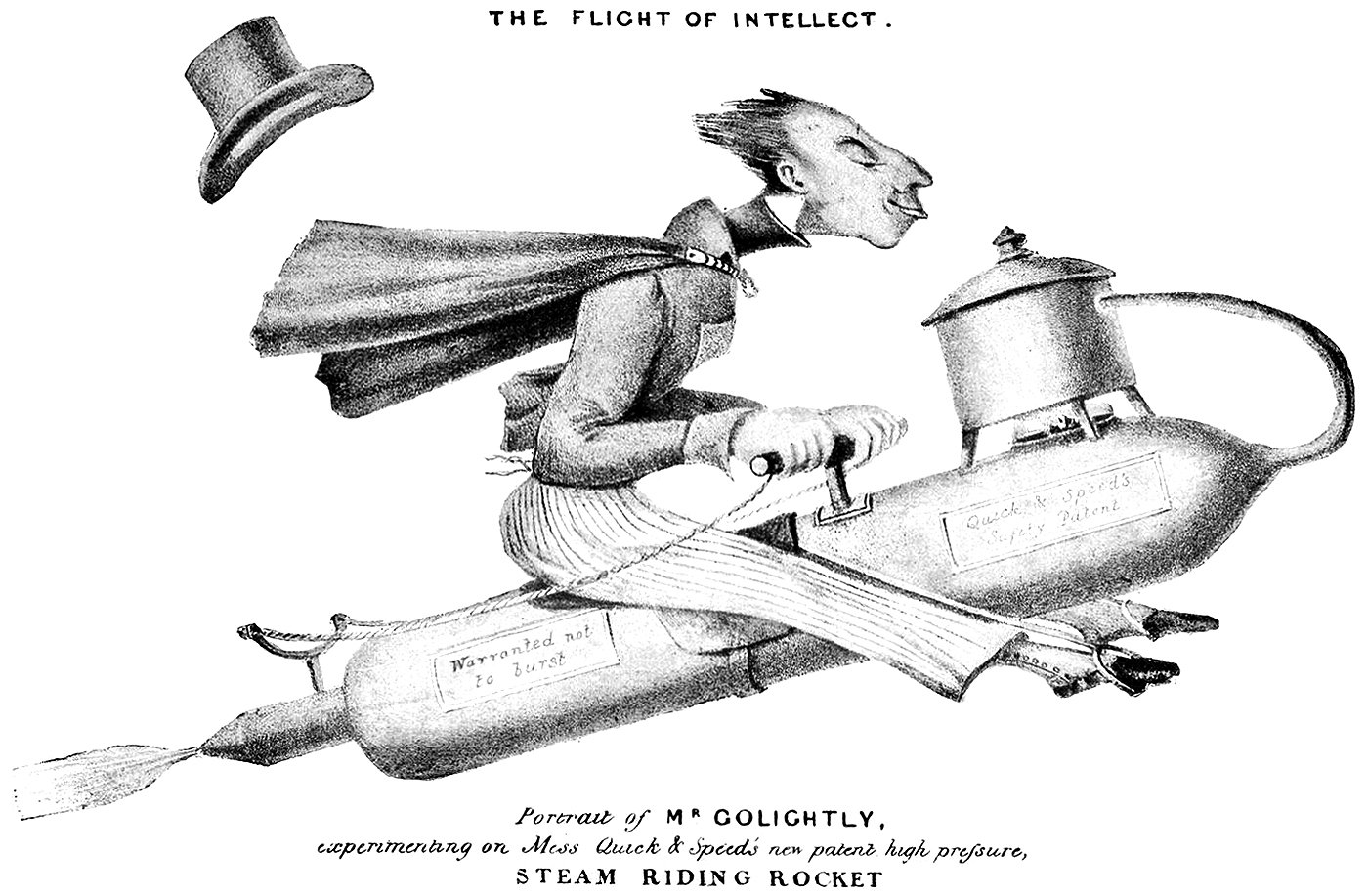

Mr. Golightly and the Flight of Intellect

Pictured here are a pair of cartoons drawn in the 1800s by Charles Tilt. They feature the character Mr. Golightly flying on a steam-powered rocket. The first, pictured above, is from 1826 and it features a well-dressed Mr. Golightly sitting on his rocket, flying fast through the air. The caption reads Portrait of Mr. Golightly, experimenting on Mess Quick & Speed’s new patent high pressure, steam riding rocket.

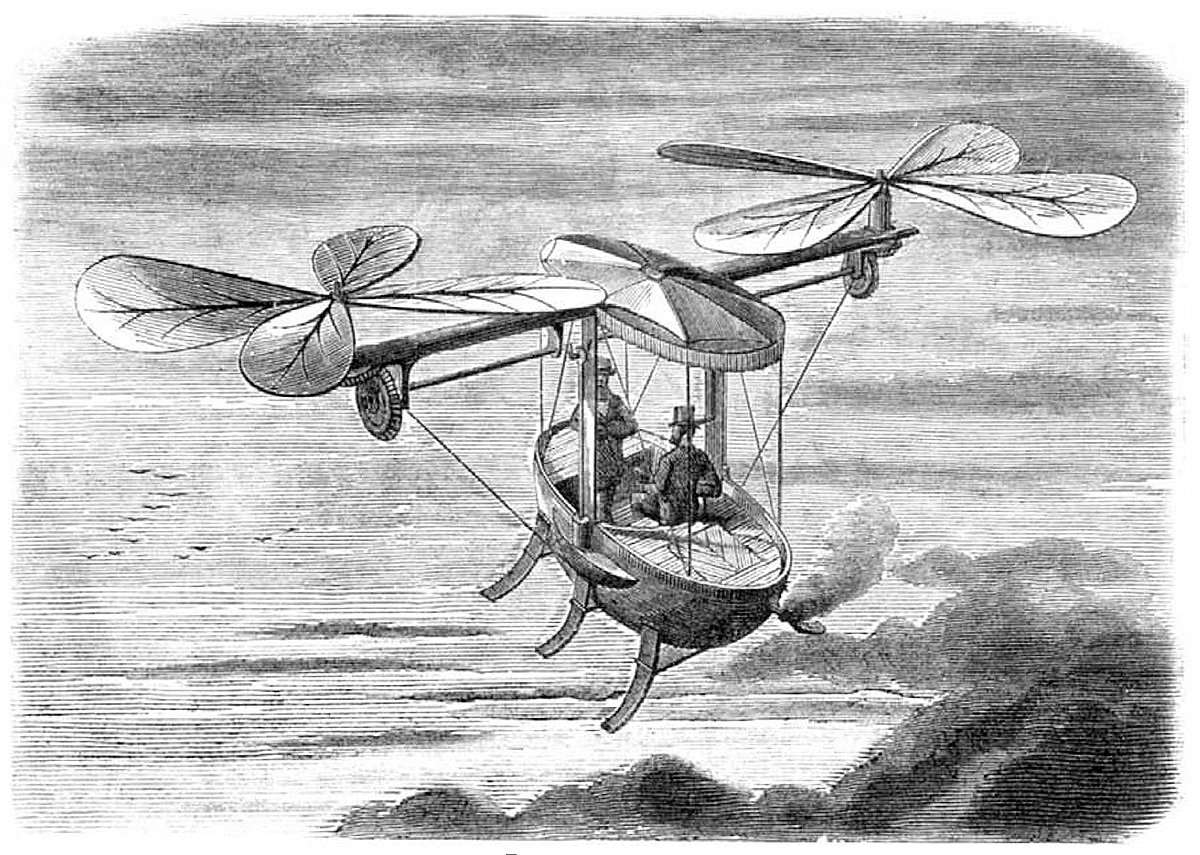

A Proposed Flying Machine

Pictured above is a proposed flying machine from an 1874 issue of Scientific American. The author is known only as W.D.G., and he wrote a detailed description of his machine to go along with the illustration shown here. Curiously, the description begins with this statement: Cannot we arouse a little more spirit and inquiry regarding the subject of a practical flying machine, and keep the ball rolling until the aim is accomplished?

Hiram Maxim’s Flying Machines

Hiram Maxim was a prolific inventor who is best known as the inventor of the first automatic machine gun, as well as a series of flying machines he built and tested between 1889 and 1894. Pictured above is one of his later designs. It consisted of a series of wings tied together with a web of struts and cables, powered by a pair of massive wooden propellers.

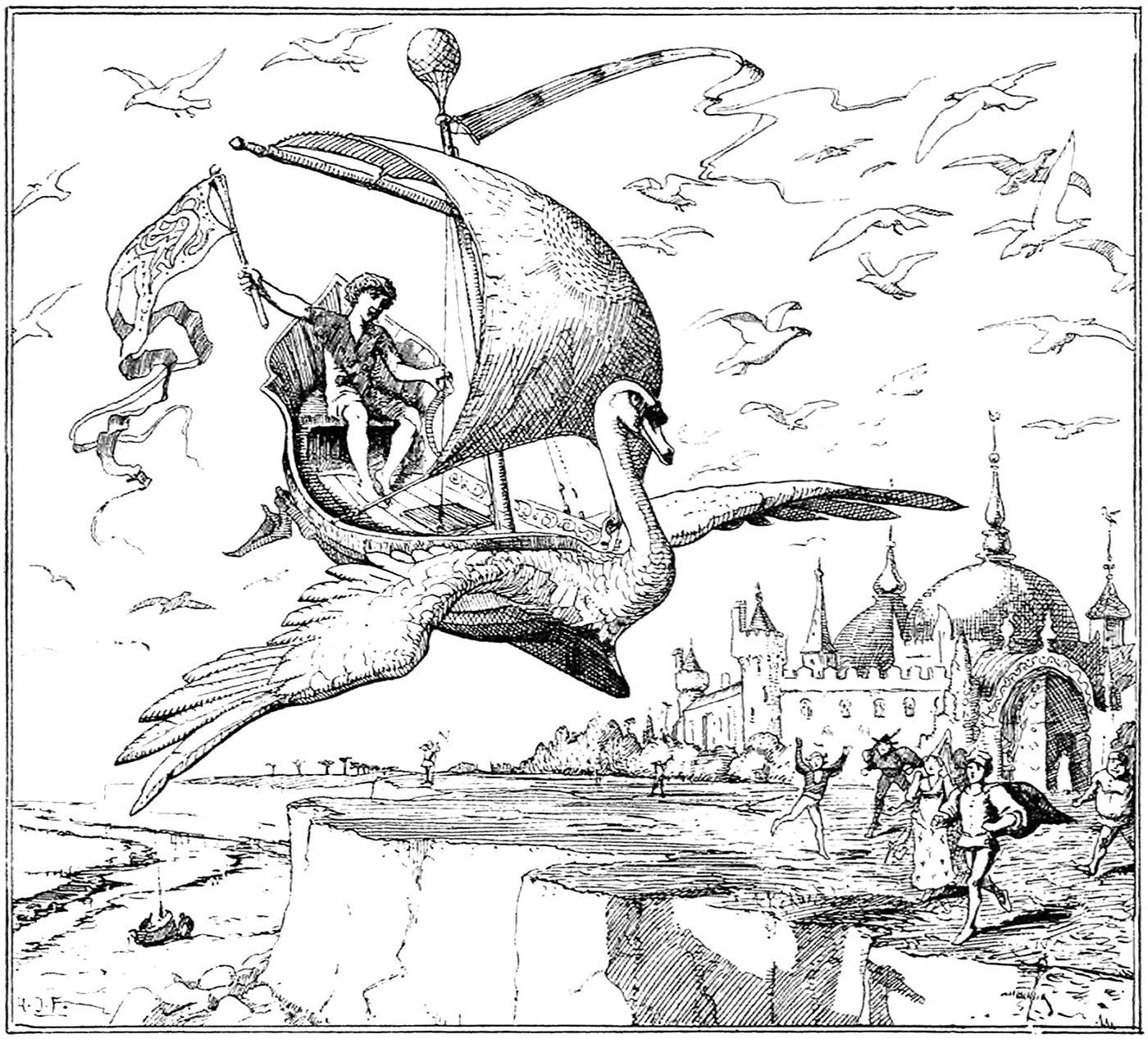

Alexander the Great’s Flying Machine

The oldest myths and legends about human flight usually involve birds and other winged creatures that were already known to fly. These creatures were ready-made-packages of sorts. Harnessing their ability to fly by means of control provided the easiest and quickest path to human flight. Pictured above is one such example of this. It’s a mythical flying machine built by Alexander the Great.

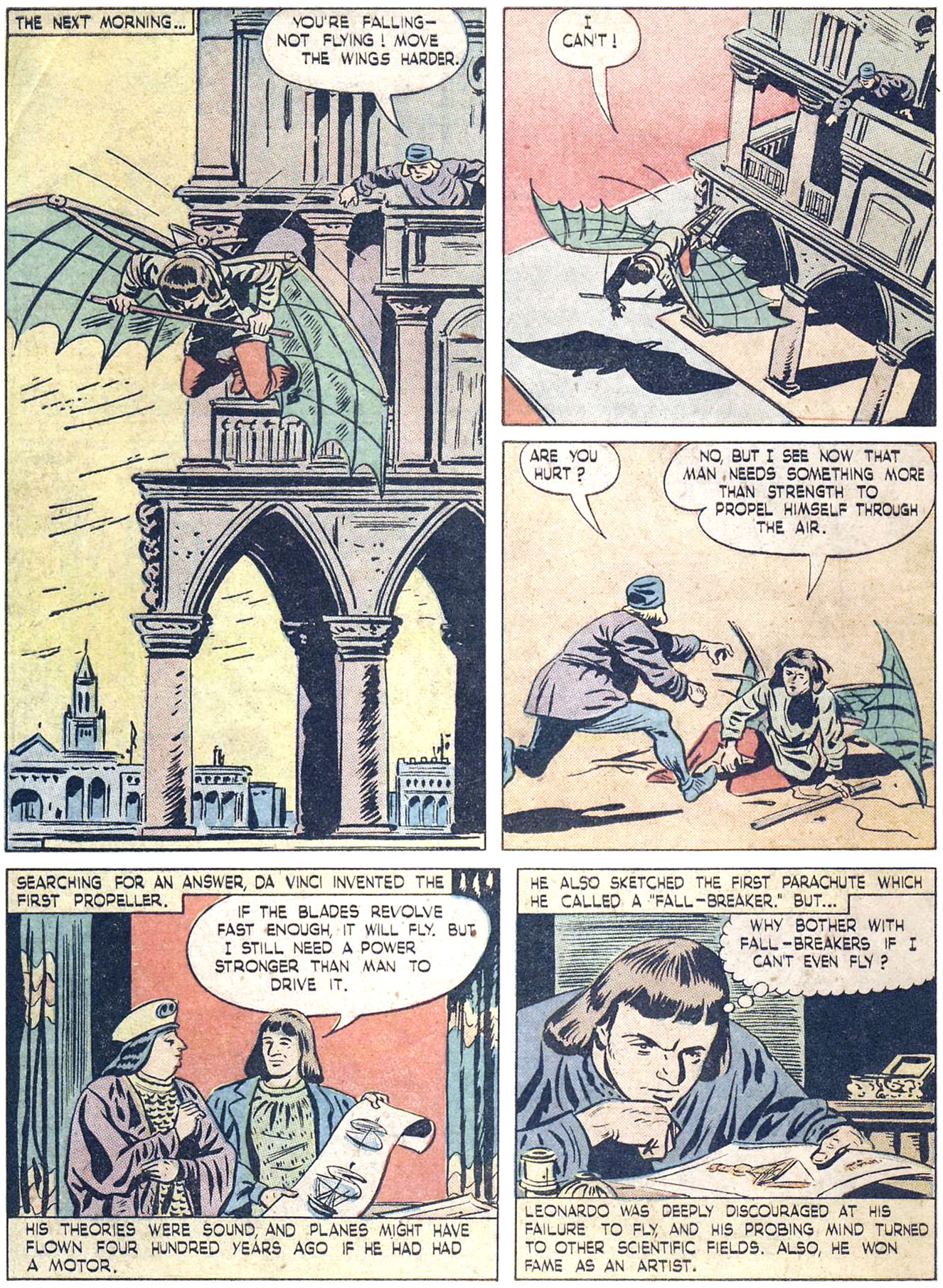

Leonardo da Vinci : 500 Years Too Soon

I see now that man needs something more than strength to propel himself through the air.

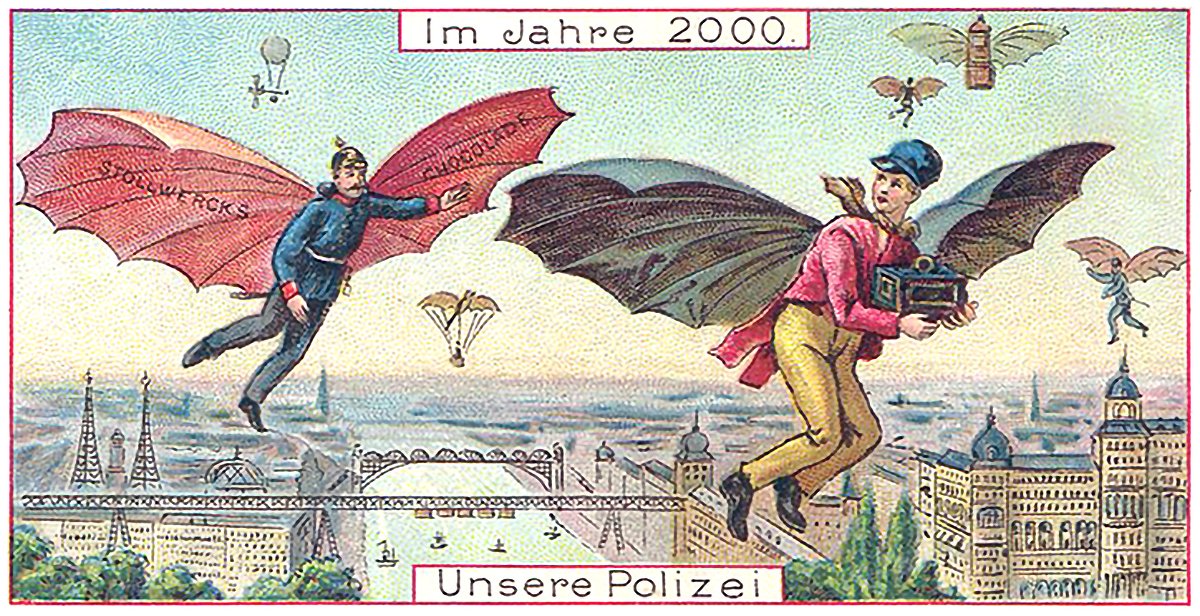

Im Jahre 2000 : In the Year 2000

The early twentieth century was a time of optimism towards the future. Aeronautics and flight were on the public’s consciousness, and there was much speculation about how the future would look once humanity conquered the skies. Pictured here is one such vision. It’s from a set of six cards titled Im Jahre 2000, which is German for In the Year 2000. What’s interesting about the set is that three of the cards deal with flight.

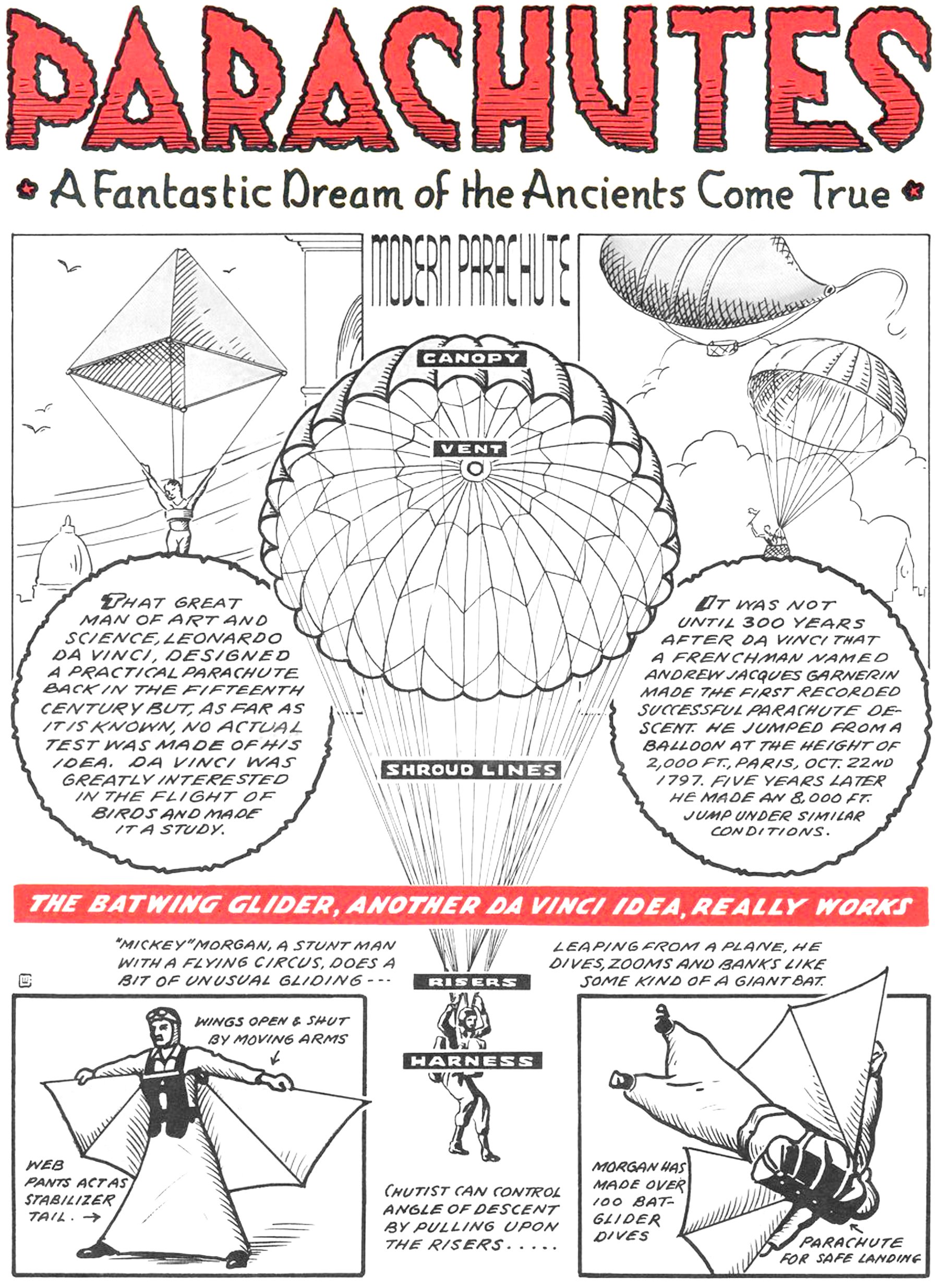

Parachutes : A Fantastic Dream of the Ancients Come True

Pictured above is a page from a War Heroes comic book from 1943. It features a few examples of parachutes and a flying suit called the Batwing Glider. At the center of the page is a modern parachute, complete with its canopy, vent, shroud lines, risers and harness. Flanking this drawing are two historical examples of parachutes. The first is a sketch from Leonardo da Vinci’s notebooks circa 1495, and the second is the world’s first successful parachute descent by André-Jacques Garnerin in 1797. This triad presents a concise, albeit incomplete history of parachute design, but it does do a good job of visually connecting a modern parachute to its ancestors.

Gustave Whitehead’s Flying Machines

Gustave Whitehead was a German-born aviation pioneer that emigrated to the United States in 1893. He subsequently built and tested a number of flying machines, and some believe he achieved the first ever powered, controlled flight. As with most claims of this nature, it’s a difficult thing to prove and will most likely always have controversy surrounding it. Because of this, his machines and the alleged flights they took have a sense of mystery about them. To add to this mystery, Whitehead experimented with many different types of machines, including both manned and unmanned machines and both gliders and self-powered machines.

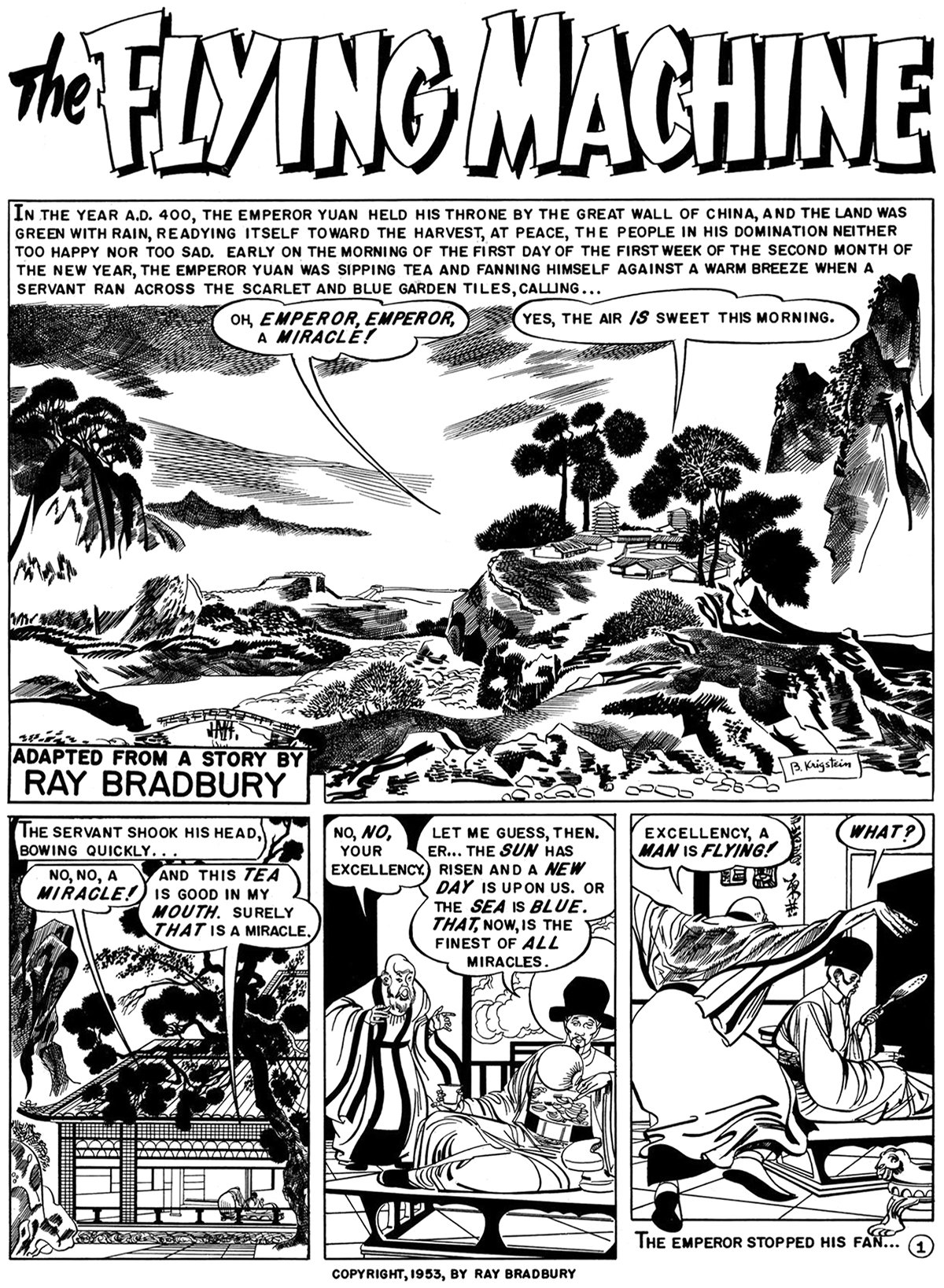

The Flying Machine by Ray Bradbury

With great power comes great responsibility. This is the major theme of Ray Bradbury’s short story from 1953, titled The Flying Machine. It was adapted into a comic in 1954 by Al Feldstein, and the full piece is pictured here. It tells the story of a meeting between an emperor and an inventor who has built a flying machine. The inventor is an optimist who experiences the full delights of flying, while the emperor is a pessimist who fears the technology will fall into the wrong hands. It’s a theme that runs much deeper than human flight, but Bradbury’s choice to feature the flying machine demonstrates the power of flight for humanity.

Minnikin’s Flying Ship

‘Now go over fresh water and salt water, over hill and dale, and do not stop until thou comest to where the King’s daughter is,’ said Minnikin to the ship, and off it went in a moment over land and water till the wind whistled and moaned all round about it.

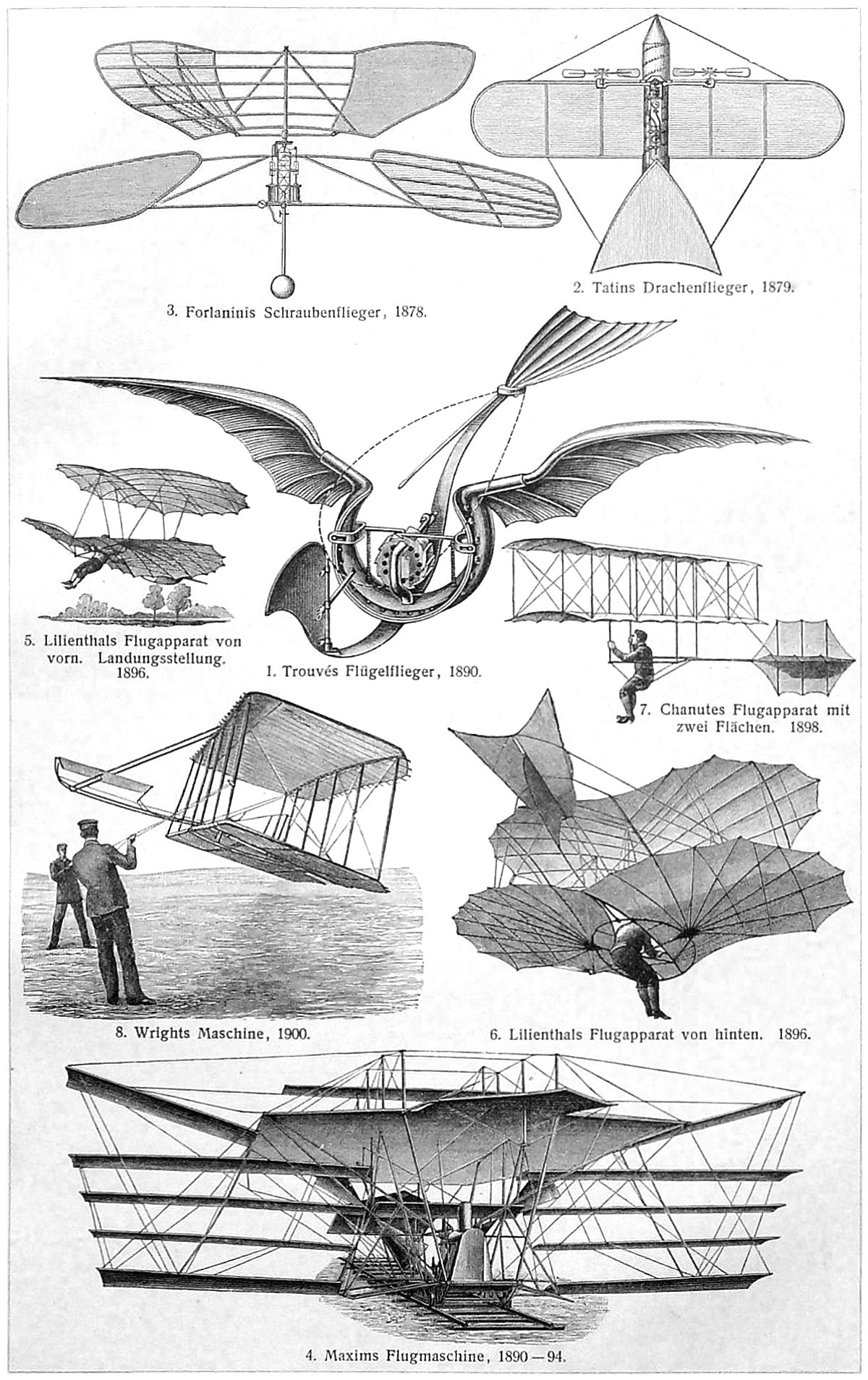

Early Aeronautics

Pictured above is a collage of early flying machines, originally published in the German encyclopedia Meyers Konversations Lexikon. I love collages like this because the illustrator inevitably must pick and choose which examples to show. This is most likely done for a combination of reasons, including available illustrations, the most famous examples, and page layout.

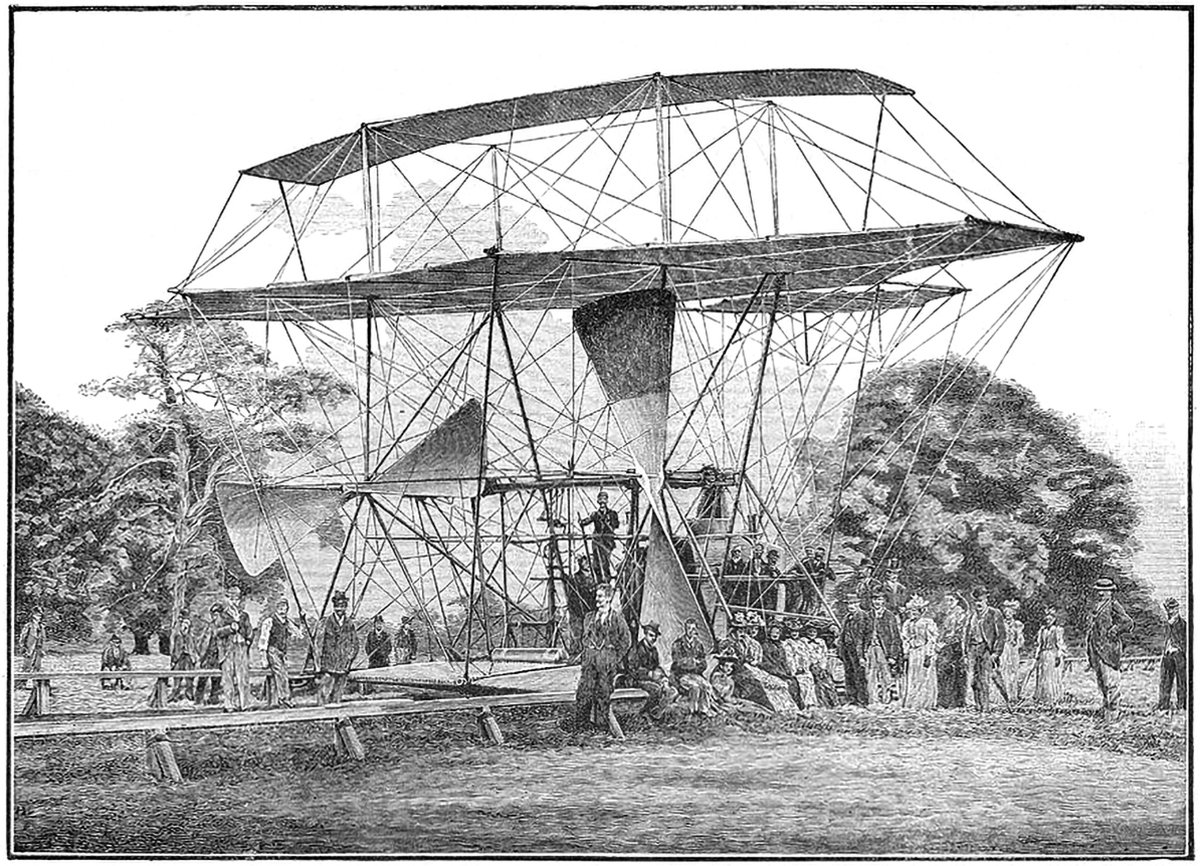

E.P. Frost’s Ornithopters

Pictured above is a photo of E.P. Frost’s second ornithopter prototype. It consisted of a large a pair of wings and a metal scaffold, and it was powered by an internal combustion engine. According to Frost, the machine successfully achieved liftoff under its own power in 1904. This wasn’t a sustained flight, however, but rather a jump or a hop.

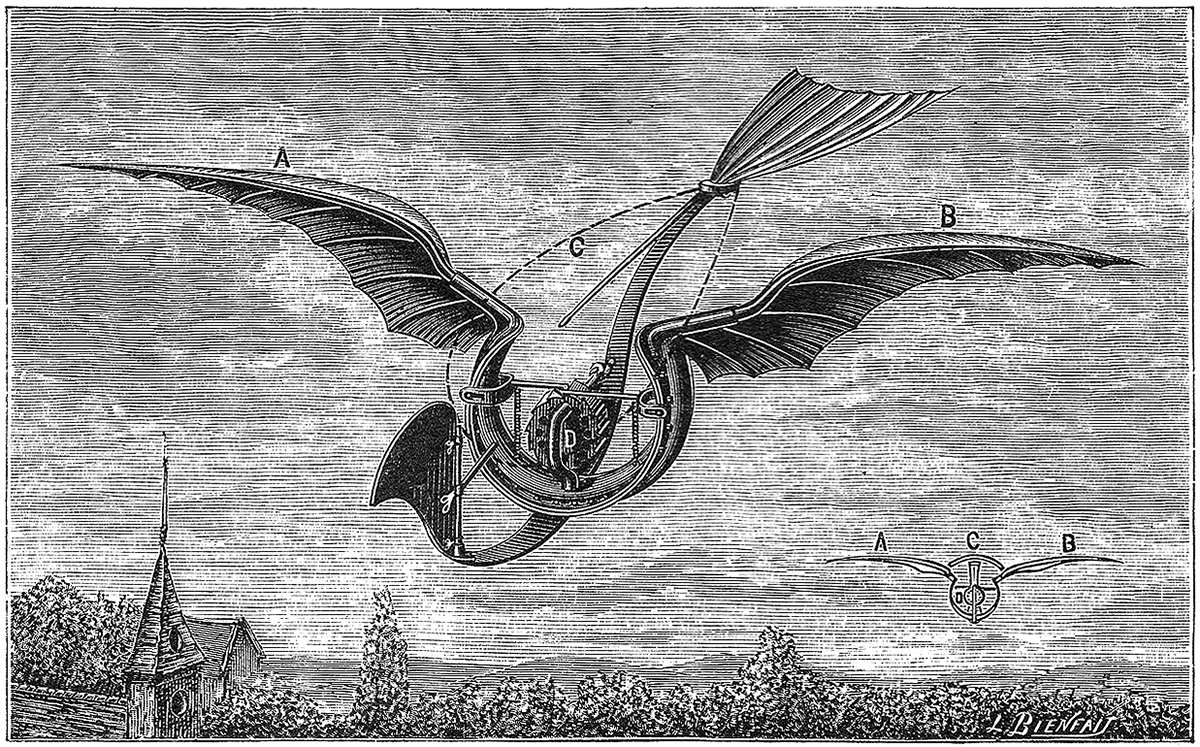

Gustave Trouvé’s Flügelflieger

Pictured above is an ornithopter design from 1891 by French polymath and inventor Gustave Trouvé. It was called the Flügelflieger, which means winged flyer in German. It featured a pair of wings, a tail, a front rudder, and it was powered by a centrally-placed rapid-succession gun cartridge. Due to the gunpowder charges, the machine was quite loud when flapping. It did work though; according to Trouvé it made a successful flight of 80 meters (262 feet) on 24 August 1891.

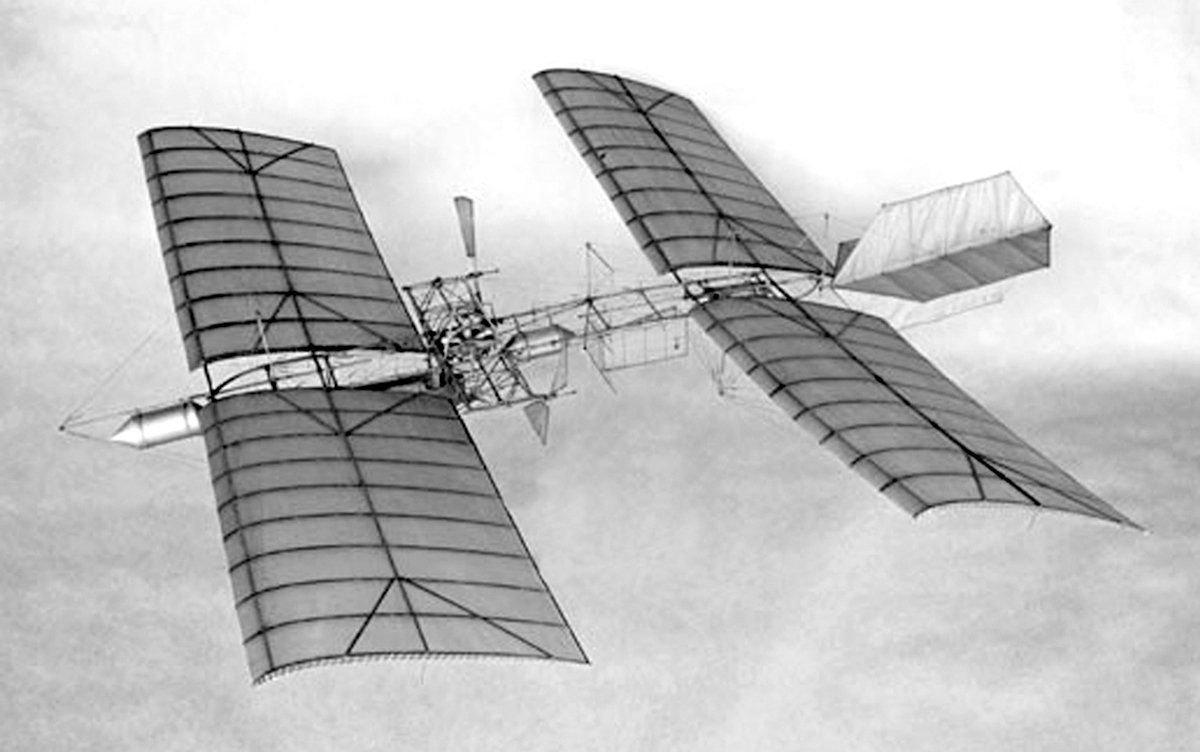

Samuel Langley’s Aerodrome

Samuel Langley was an astronomer and physicist who was the third secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. He was also a pioneer of aviation, most famous for his designs of the Langley Aerodrome, which he built and tested from 1901 to 1903. Pictured above is a photo of his Aerodrome No. 5, which was a pilot-less model that had success flying. Langley was unable to repeat this success with larger, piloted designs, however.

The Jatho Biplane and a Challenge to the Wright Brothers

Pictured above is the Jatho Biplane, built in 1903 by the German aviation pioneer Karl Jatho. During 1903, Jatho made a series of low flights with his machine outside Hanover, Germany. These flights took place a few months before the Wright Brothers achieved powered, controlled flight. We don’t know for sure if the Jatho Biplane was controlled, however. If it was, that means the Wright Brothers weren’t the first to achieve flight. If it wasn’t, the Jatho Biplane is just another prototype that got close, but didn’t actually achieve flight.

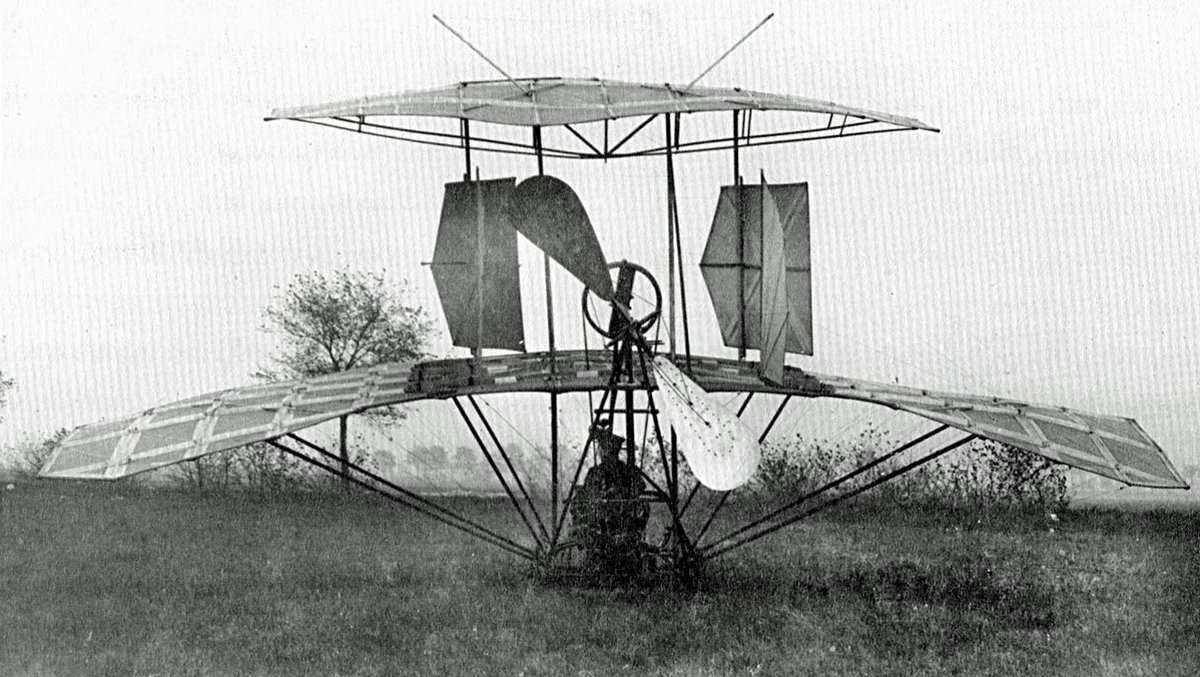

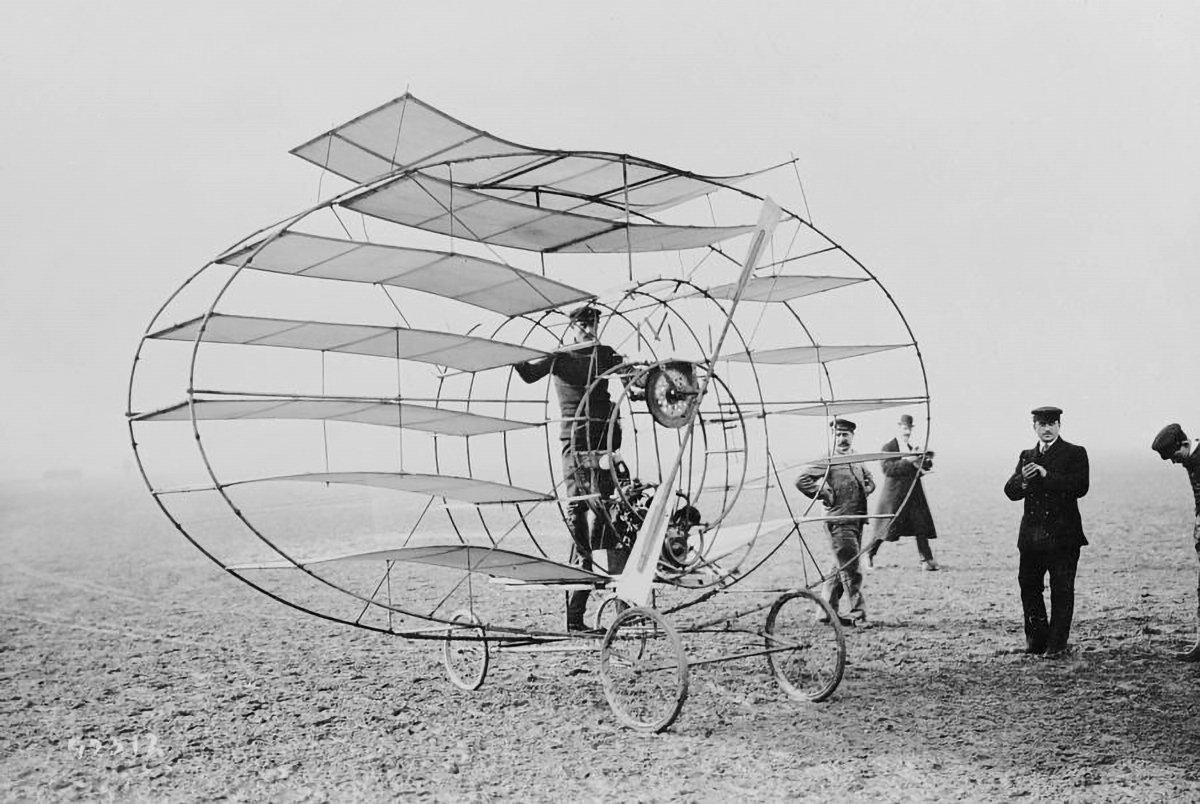

The Marquis Multiplane

If two wings can provide enough lift to make an aircraft fly, surely adding more wings must make it fly even better, no? It’s a silly question by today’s standards, but in the early days of flight it was a legitimate inquiry to be studied. One man who decided to test the theory was Marquis d'Ecquevilly, and pictured above is the Marquis Multiplane which he designed in 1908.

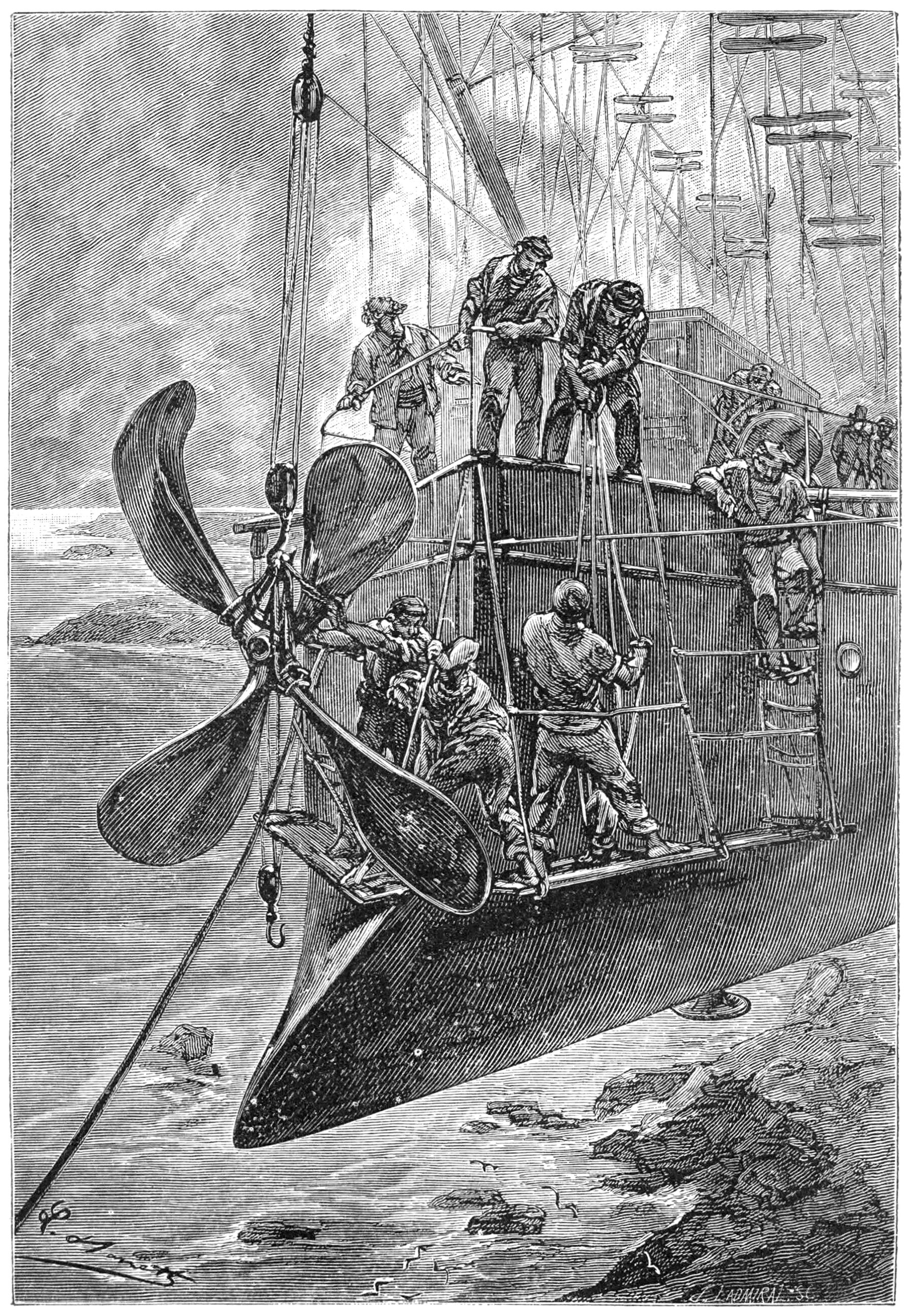

Jules Verne’s Clipper of the Clouds

Fiction has a way of reflecting and informing reality. Pictured above is an illustration from Jules Verne’s novel Robur the Conqueror, published in 1886. It shows a fictional flying machine called the Clipper of the Clouds, which was built by the novel’s titular character. Throughout the story, Verne explores the nature of flight, its effects on humanity, and the general sense of public awe in the early days of flying machines. There’s also an undertone of the God versus Ego struggle that is central to the verticality narrative.

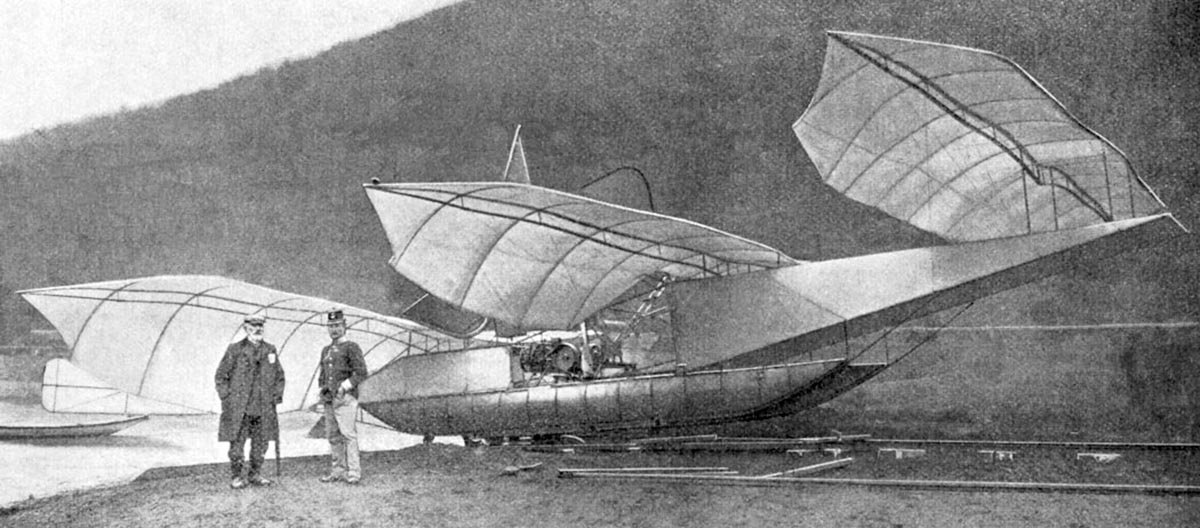

Wilhelm Kress’ Drachenflieger

Pictured above is the Drachenflieger, which was an experimental aircraft designed in 1901 by Austrian engineer Wilhelm Kress. It’s name means Dragon Flyer in German, and it was an attempt by Kress to build the world’s first heavier-than-air flying machine. The craft consisted of a central undercarriage and three large pairs of wings, each set at a different height so they wouldn’t interfere with one another. It was meant to take off and land on the water, so Kress designed it to rest on two pontoons.