Welcome to On Verticality. This blog explores the innate human need to escape the surface of the earth, and our struggles to do so throughout history. If you’re new here, a good place to start is the Theory of Verticality section or the Introduction to Verticality. If you want to receive updates on what’s new with the blog, you can use the Subscribe page to sign up. Thanks for visiting!

Click to filter posts by the three main subjects for the blog : Architecture, Flight and Mountains.

Alternate Realities : The Washington Monument

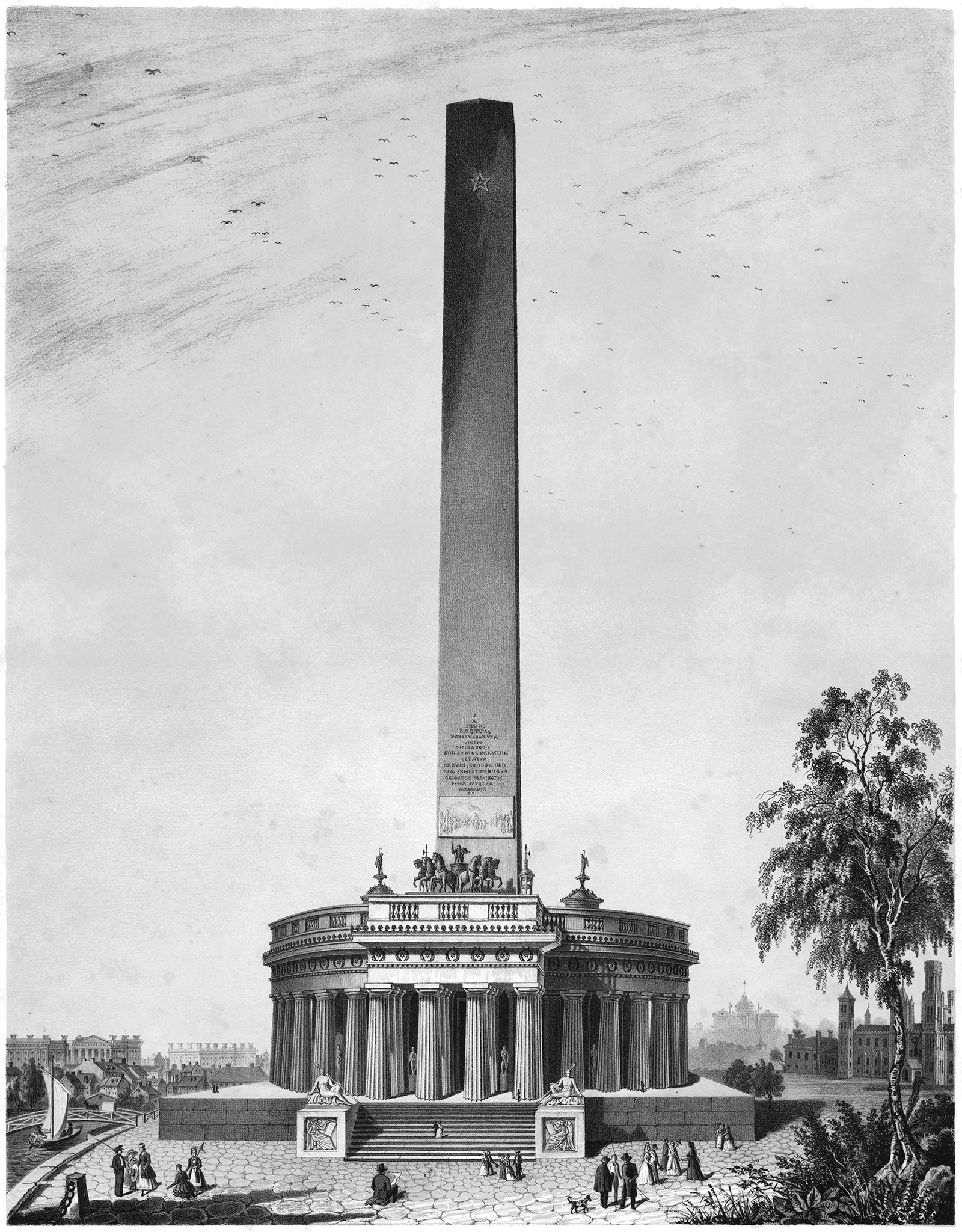

Pictured above is a proposal for the Washington Monument, designed by Robert Mills sometime around 1845. It was the winning entry of a design competition established in 1835 by the Washington National Monument Society. This design is the second of three structures that Robert Mills proposed or built for a monument to G.W., and each is based on verticality in some way.

The Origin of the Obelisk

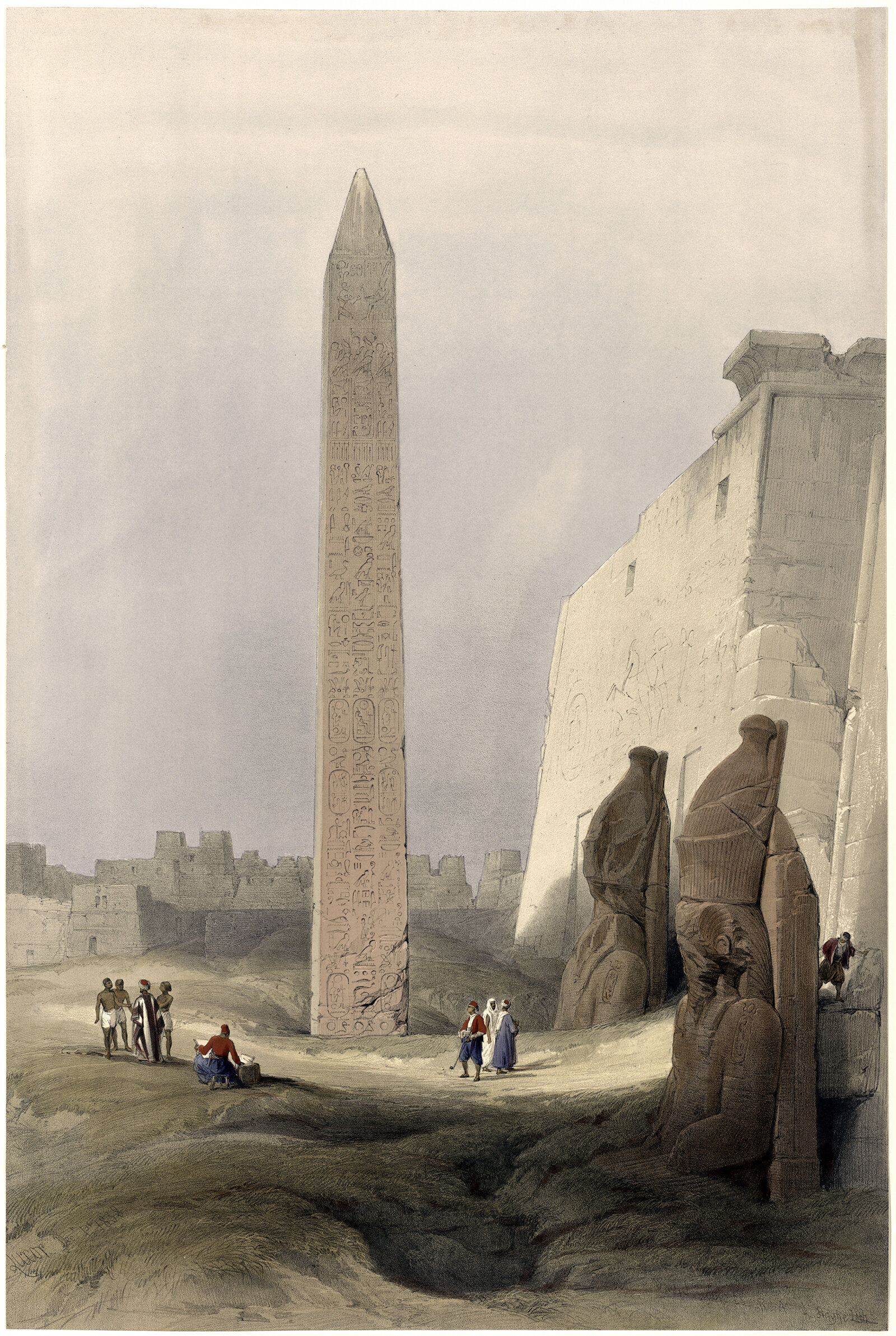

I was recently on a trip to Washington DC, and I went for a run on the National Mall. The centerpiece of the entire complex is the Washington Monument, which is a 169 m (555 ft) stone-faced obelisk. The monument is strikingly simple and quite effective at announcing its presence to the surrounding area. It got me thinking about the obelisk form, and how it’s meaning has changed over the centuries. What was once an integral part of a temple complex has become a singular expression of verticality.

A Design for a National Memorial

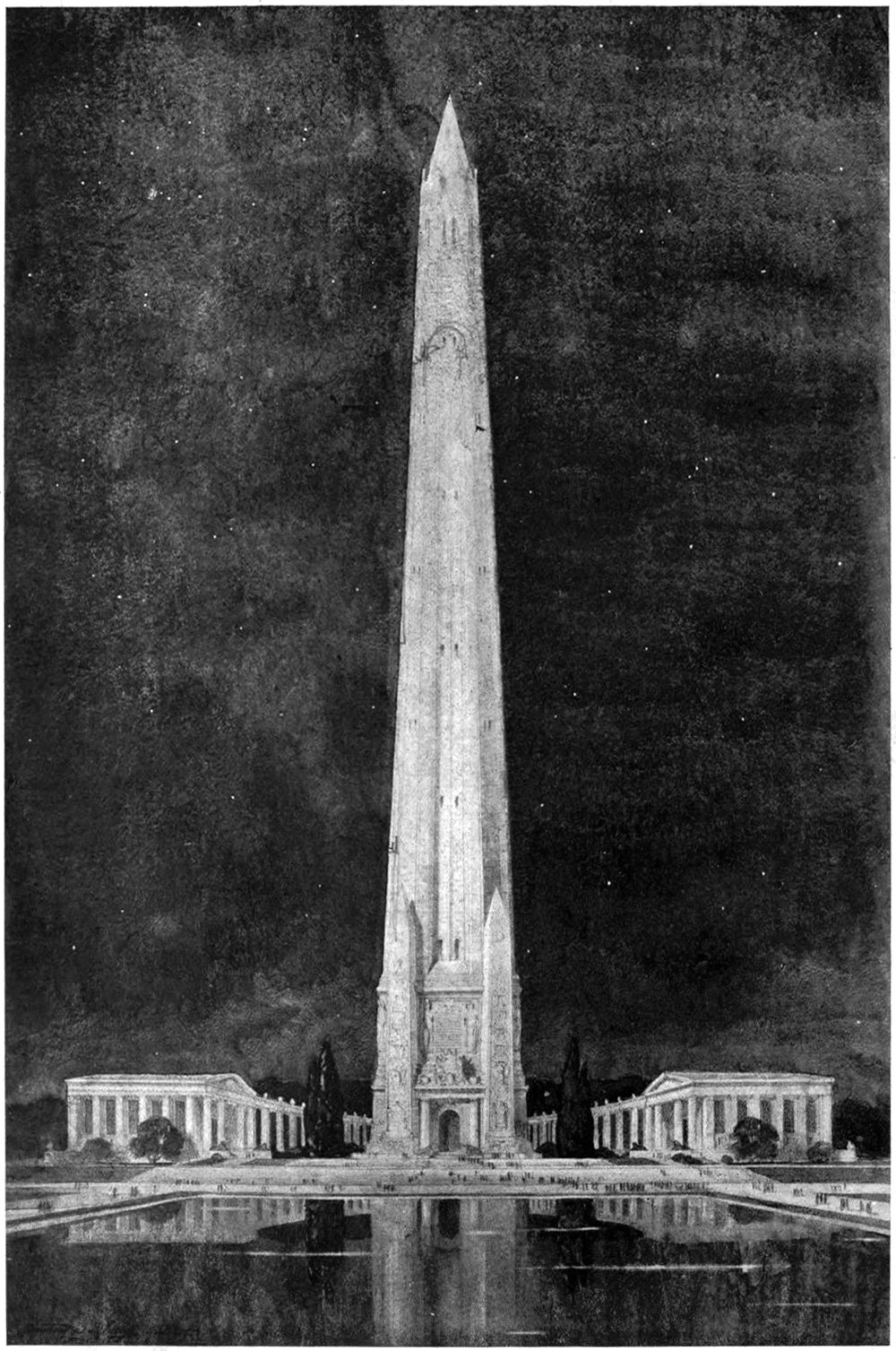

Monuments and memorials are tricky beasts to design. Unlike a normal building, they’re imbued with meaning and symbolism that can be highly subjective. They’re not just buildings, but repositories for history and memory. This means they carry responsibilities to the person or event they are meant to symbolize. That’s what makes the above illustration so difficult to understand. It’s described only as Design for National Memorial. This is tough, because it doesn’t even make a claim to what it’s memorializing. One thing is clear, however; the designer was motivated by verticality.

Constant-Désiré Despradelle’s Beacon of Progress

He was possessed by the idea of a monument embodying the characteristics of American civilization, to be a memorial to the genius of the American people and a reminder of the glories of the Columbian Exposition in Jackson Park. These words describe the feeling of Constant-Désiré Despradelle after he visited the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893 in Chicago. The exposition saw an entire complex of temporary buildings built in Jackson Park, only to be demolished after the fair. For Despradelle, Chicago needed a permanent monument to embody the spirit and grandeur of the fair. He set to work designing his vision, and the final result is pictured above.

Verticality, Part VI: Archetypes

Man’s initial attempts to get closer to the sky in each of the five cradles of civilization

How does one achieve physical Verticality? At the most basic level, we can get closer to the sky in two ways. First, we can recreate the human body with singular elements that express height on their own. These objects can be seen as proxies for our own bipedal bodies. Second, we can physically raise the surface under our feet in order to raise our bodies up closer to the sky. These constructions can be seen as recreations of mountains, which are the highest places we can reach in the natural landscape. As our ancestors set out to externalize their need for Verticality, they experimented with both of these methods.