Welcome to On Verticality. This blog explores the innate human need to escape the surface of the earth, and our struggles to do so throughout history. If you’re new here, a good place to start is the Theory of Verticality section or the Introduction to Verticality. If you want to receive updates on what’s new with the blog, you can use the Subscribe page to sign up. Thanks for visiting!

Click to filter posts by the three main subjects for the blog : Architecture, Flight and Mountains.

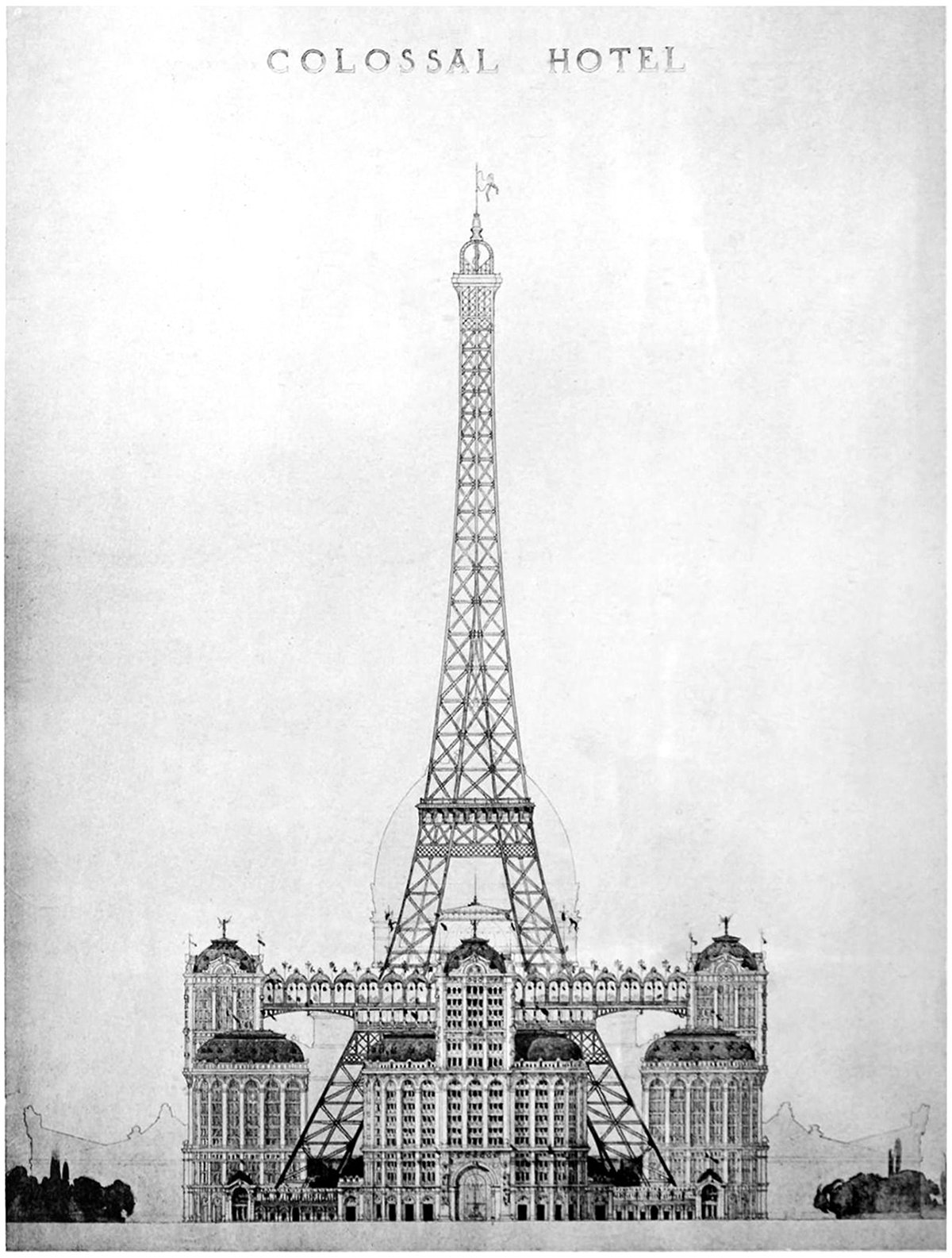

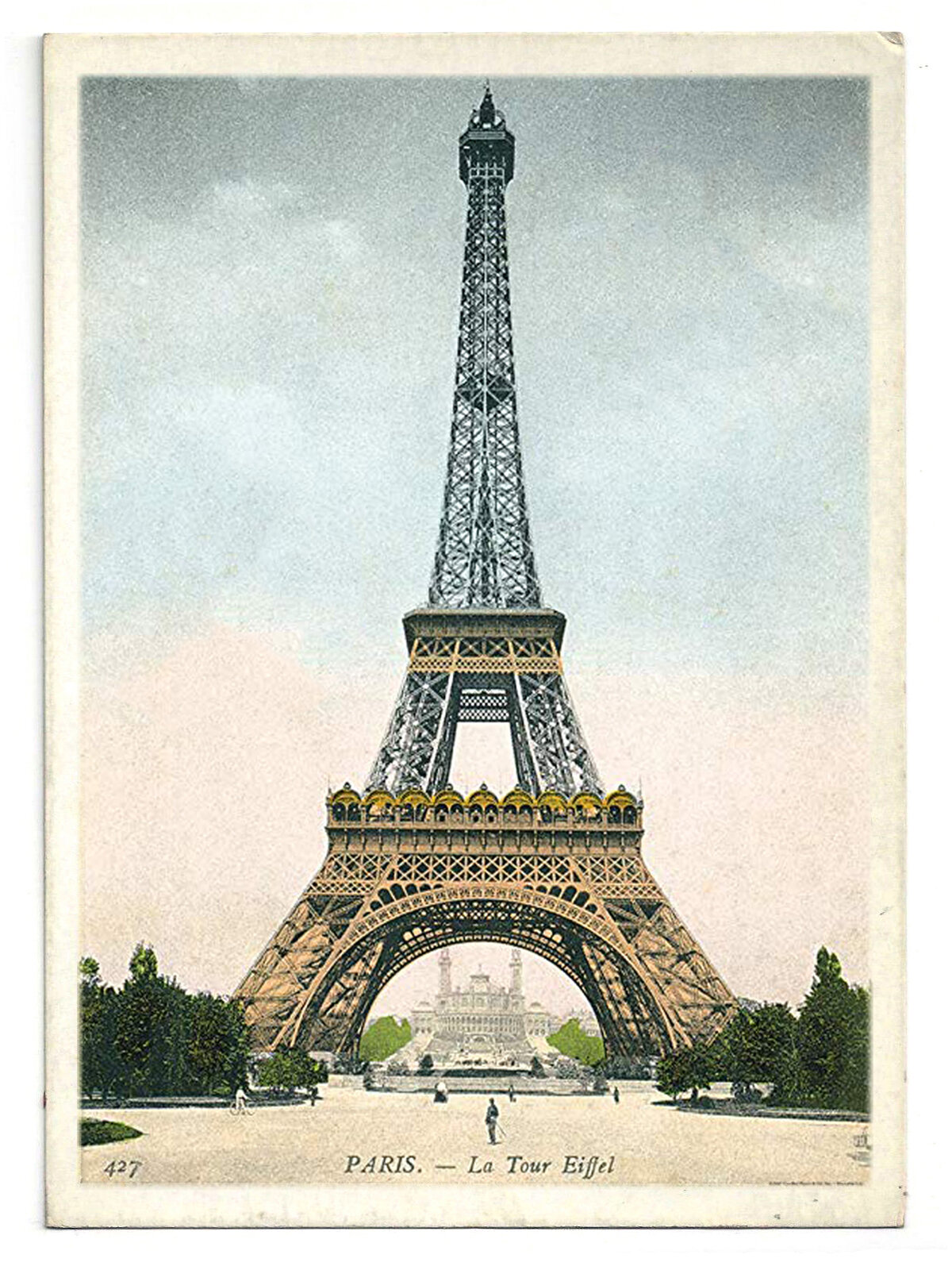

Alternate Realities : A Colossal Hotel at the Eiffel Tower

Pictured here is a proposal to put a colossal hotel at the base of the Eiffel Tower. It was proposed as part of the 1900 World’s Fair, called the Exposition Universelle, but it never got built. This elevation is the only drawing we have, which makes sense because most people who see the drawing would dismiss it immediately. The idea of filling up the void under the structure would destroy much of the Eiffel’s charm.

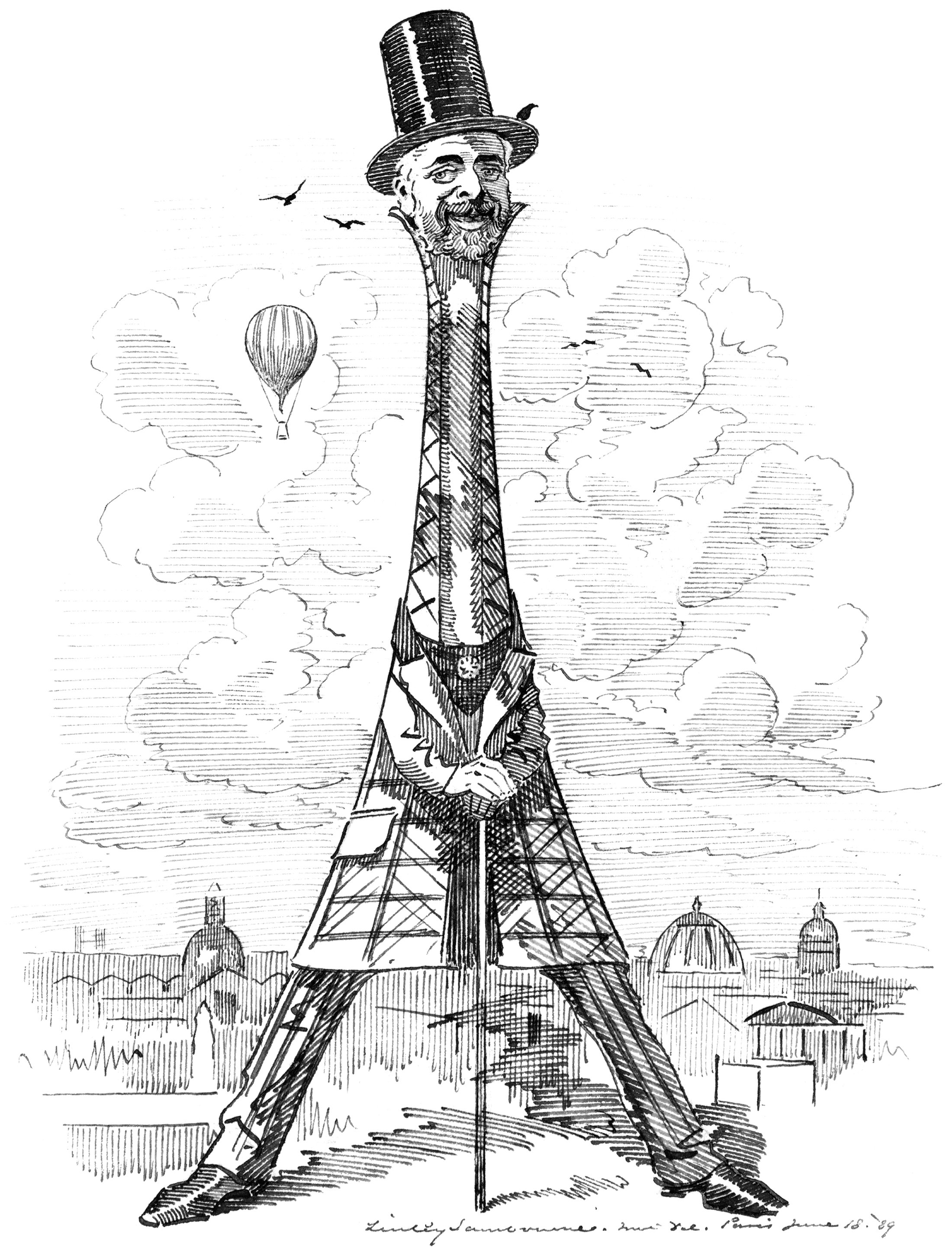

Eiffel as his Tower

Our buildings reflect our values and needs. This is especially true of our tall buildings, because they cost so much to build. When the Eiffel Tower was built in Paris, it reflected a worldwide drive for height in our buildings that was emerging at the time. It was a such a powerful statement of verticality that the man who designed it became something of a celebrity. He became linked with the tower in the eyes of the public, so much so that it was named after him like one of his children. This rarely happens with a building, but it demonstrates just how big an impact the Eiffel Tower had on the world.

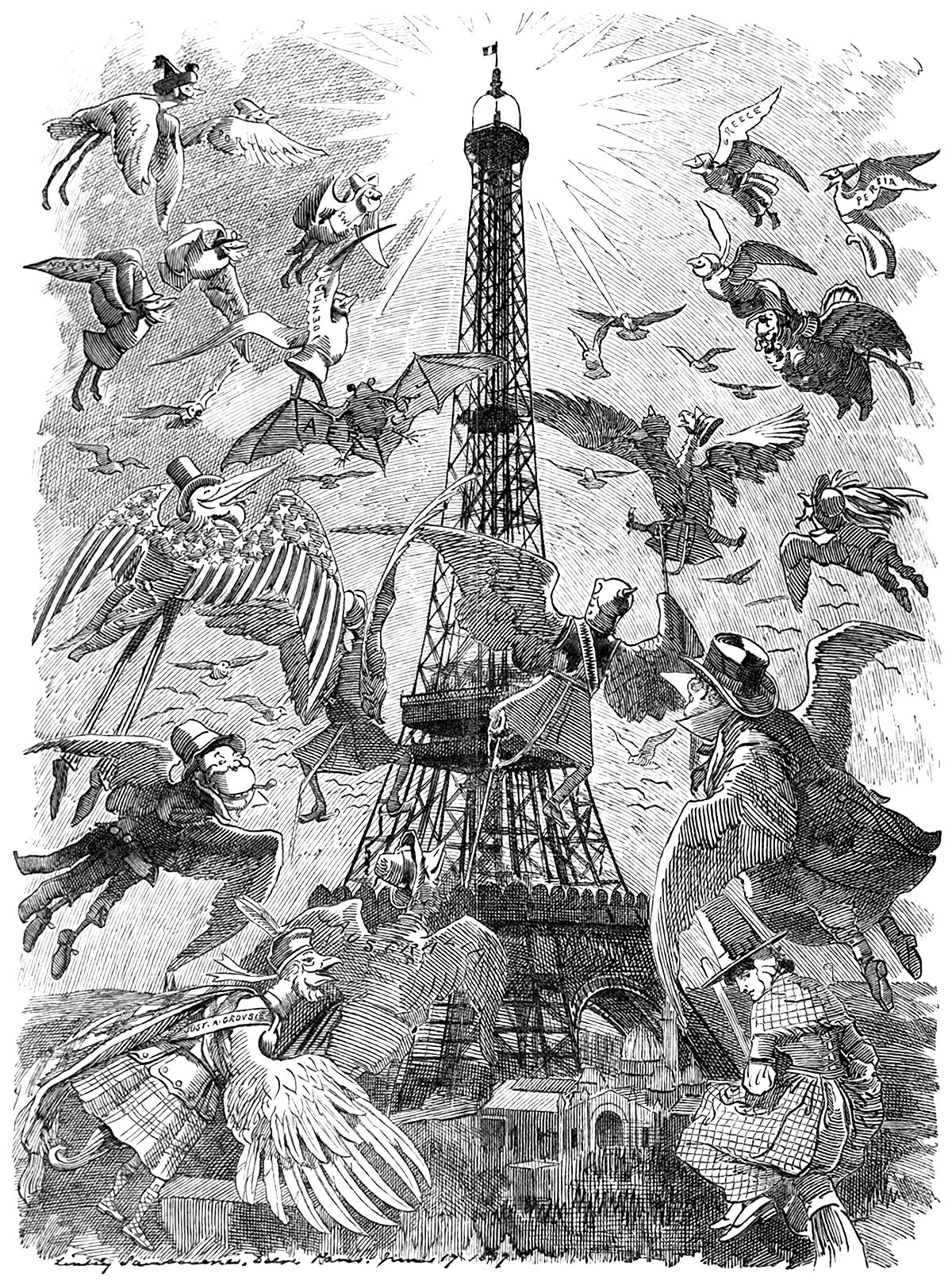

The Eiffel Tower Effect

When the Eiffel Tower was completed in 1889 for the World’s Fair in Paris, it changed the world. It re-defined what humans were capable of, and it gave the city of Paris an architectural icon that hasn’t faded with age. It was the tallest structure in the world, and it allowed its visitors to achieve verticality. As such, upon its completion the world took notice. Countless media sources reported on the structure, and it instantly took its place on the world stage. Pictured above is one such example of this. It’s an illustration from an 1889 issue of Punch magazine, and it shows a flock of birds flying toward the Eiffel Tower. These birds represent the countries of the world, and the piece was meant to symbolize the world’s envy for the iconic tower.

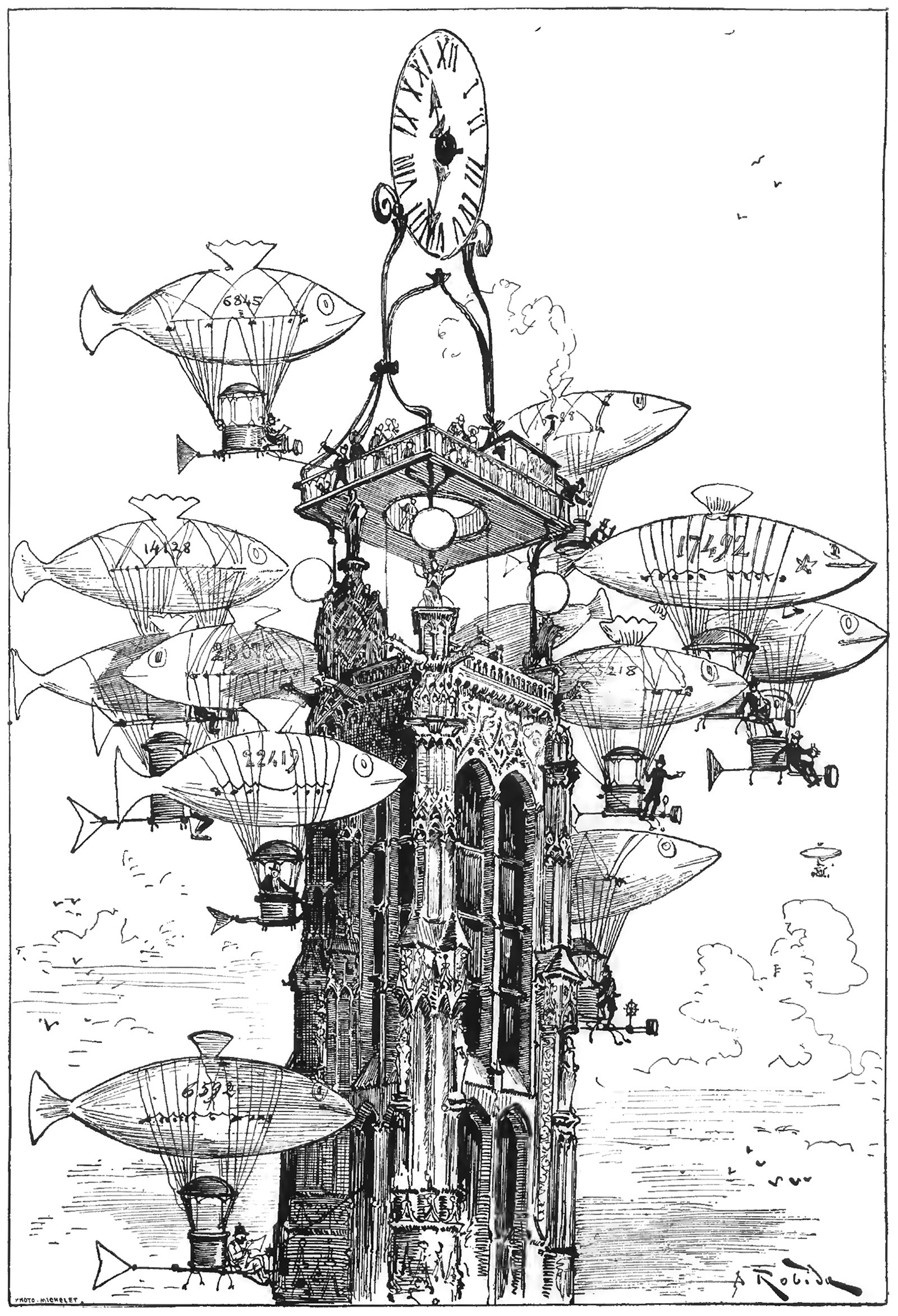

An Aerocab Station atop the Tour Saint-Jacques

The above illustration was drawn by Albert Robida for his 1883 novel Le Vingtième Siècle, or The Twentieth Century. This illustration was titled La Station d'Aerocabs de la Tour Saint-Jacques, or The Aerocab Station of the Tour Saint-Jacques, and it shows a raised platform and clock atop the iconic Parisian structure. Flocking around the tower is a group of dirigibles made to look like fish. What’s charming about the image is how the cluster of dirigibles resemble a school of fish, almost crowding out the tower itself from the image.

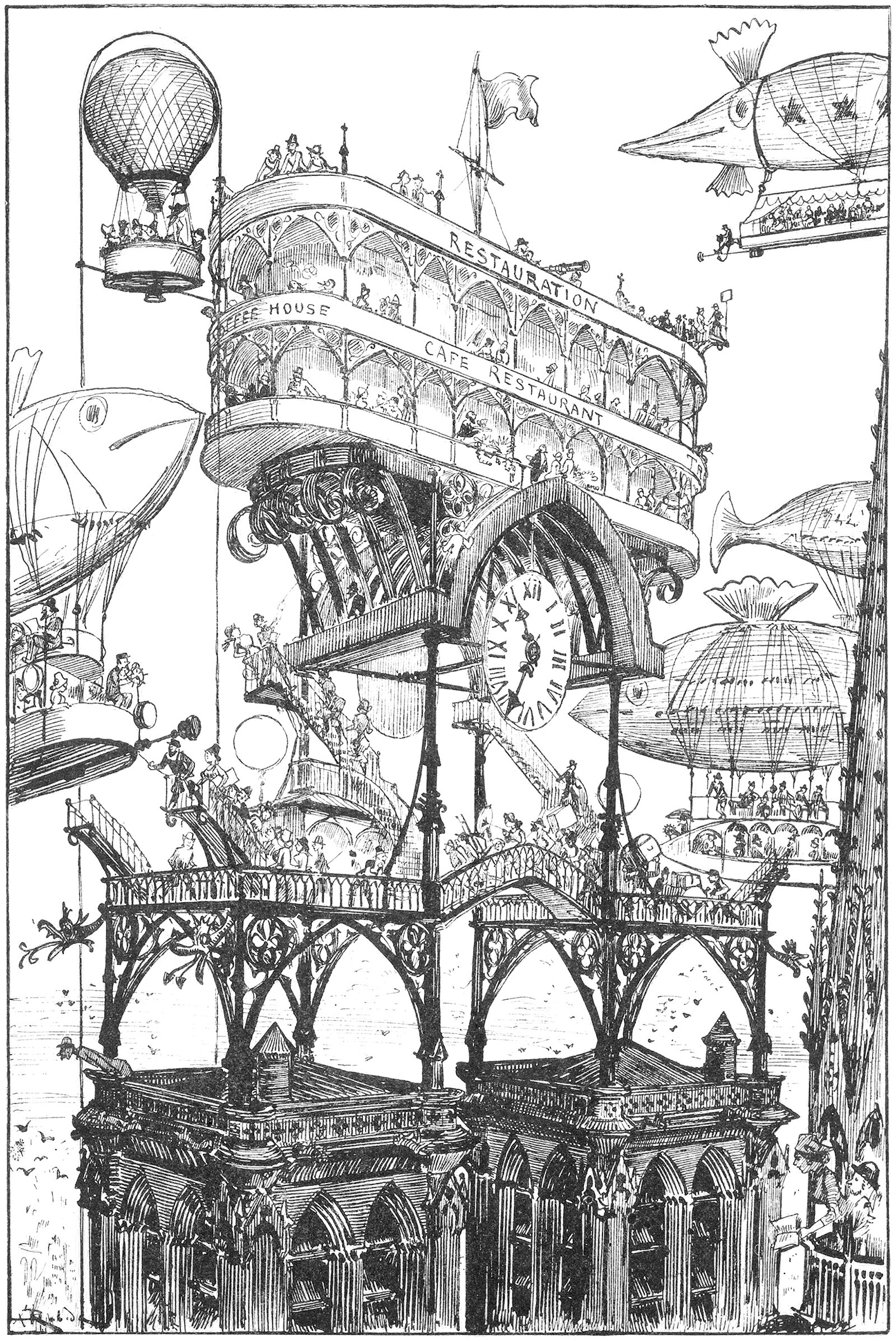

An Airport on top of Notre Dame

The above illustration was drawn by Albert Robida for his 1883 novel Le Vingtième Siècle, or The Twentieth Century. The novel describes a future vision for Paris in the 1950’s, focusing on technological advancements and how they would affect the daily lives of Parisians. Here he shows an elaborate transit station built on top of the bell towers of the Notre Dame Cathedral. It’s a wonderfully ambitious idea, and it represents modernity overtaking history.

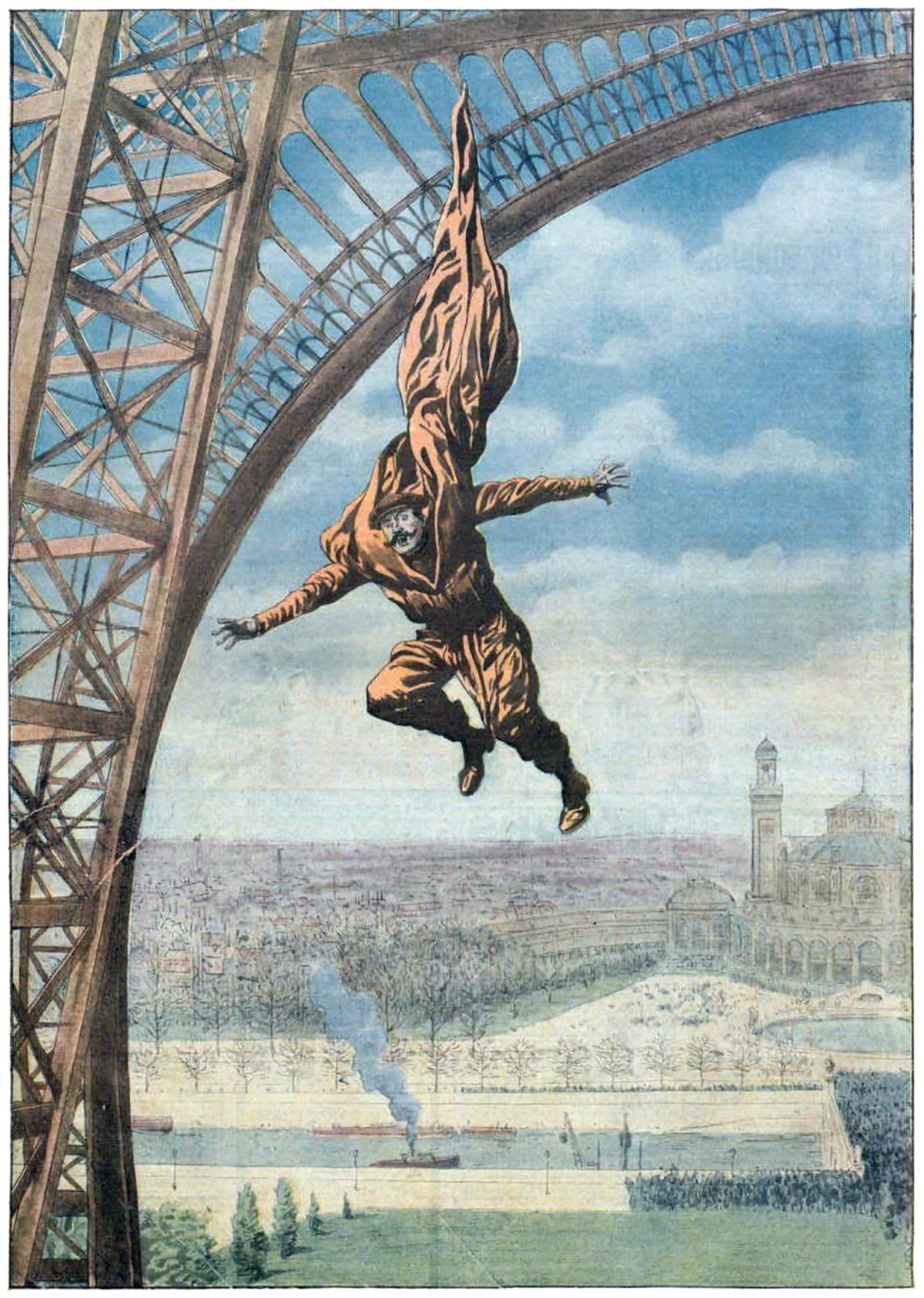

Franz Reichelt’s Fatal Leap from the Eiffel Tower

Pictured above is an illustration showing Franz Reichelt, a French tailor and inventor who was an early pioneer of parachuting. He had developed a wearable suit for pilots that would expand into a parachute should they need to eject themselves from their aircraft. He tested the design from the first deck of the Eiffel Tower in 1912, falling to his death after the parachute failed to open properly.

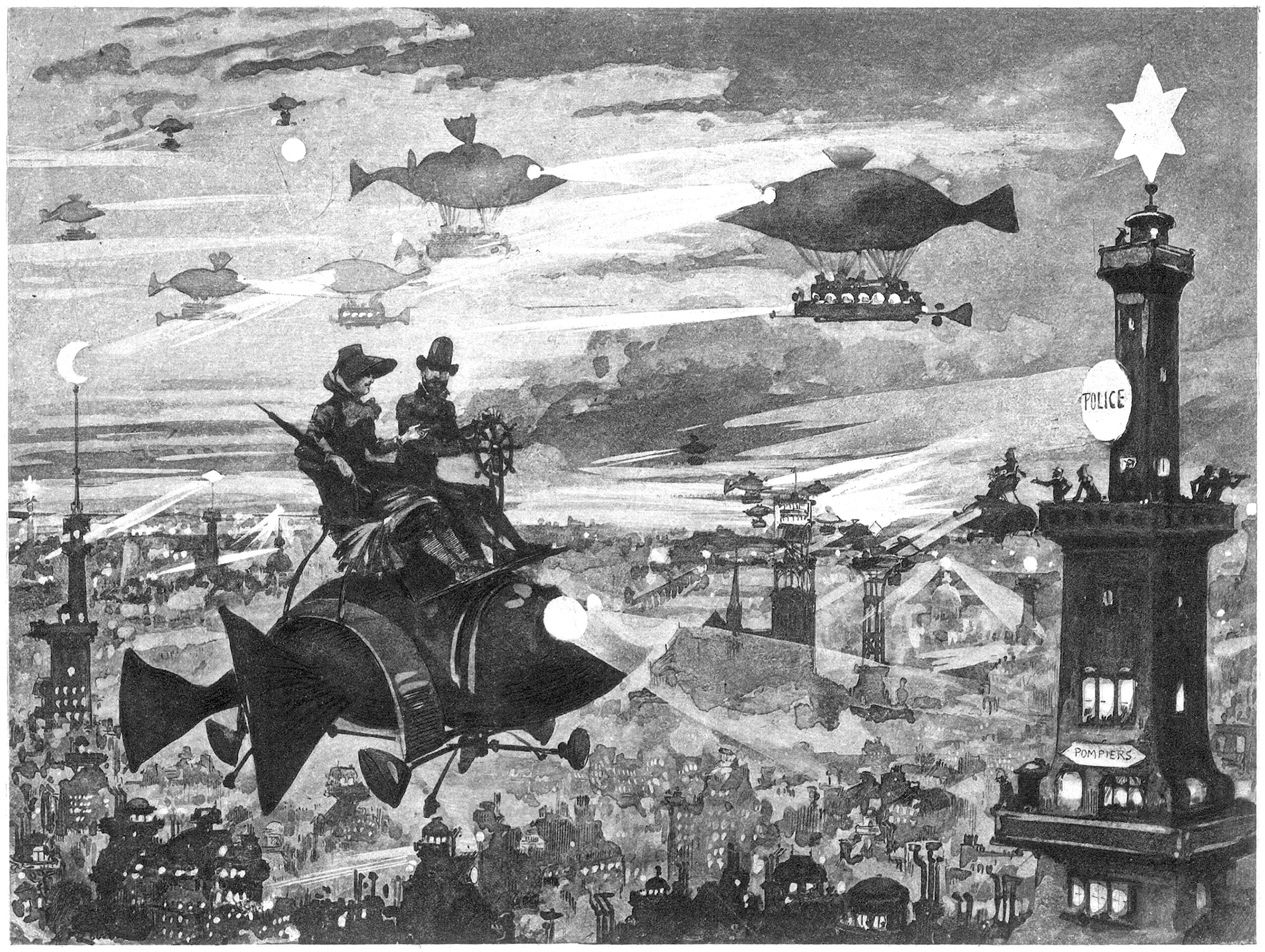

Albert Robida’s Vision for Paris

The above illustration was drawn by Albert Robida for his 1883 novel Le Vingtième Siècle, or The Twentieth Century. The novel describes a future vision for Paris in the 1950’s, focusing on technological advancements and how they would affect the daily lives of Parisians. Here he shows a vision for the night sky above Paris, which is dotted with various types of flying machines.

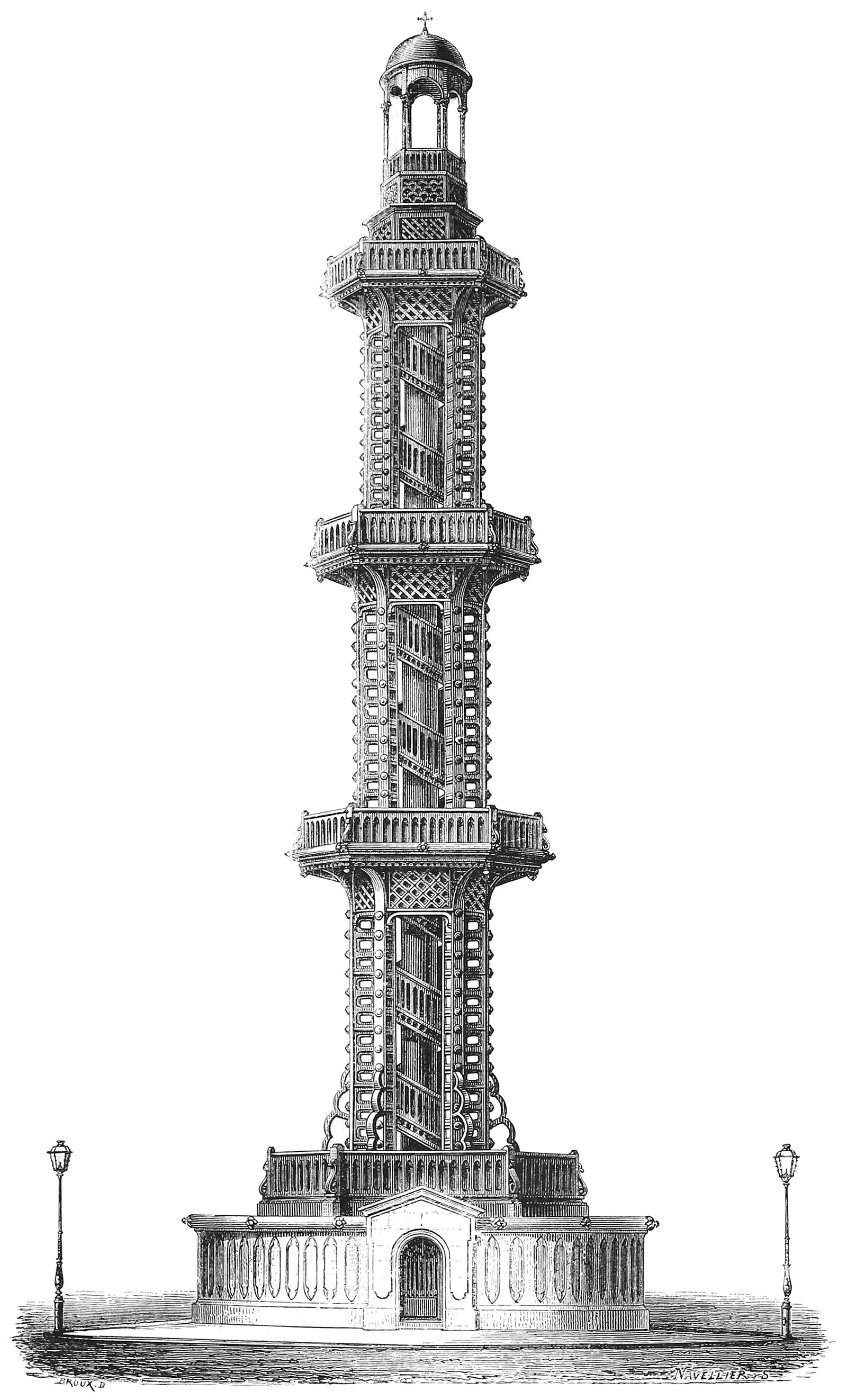

The Grenelle Artesian Well of Paris

Pictured above is the Grenelle Artesian Well in Paris, built from 1834 to 1841. During these seven years, an 8-inch diameter hole was drilled to a depth of roughly 550 meters (1,800 feet) below the earth’s surface. This process of construction took place far below ground, but in the end the well was marked with a 42 meter (138 feet) tower and fountain, placed a block away from the well itself. The tower was a deft mixture of uses, including a fountain, a sculpture, and an observation deck.

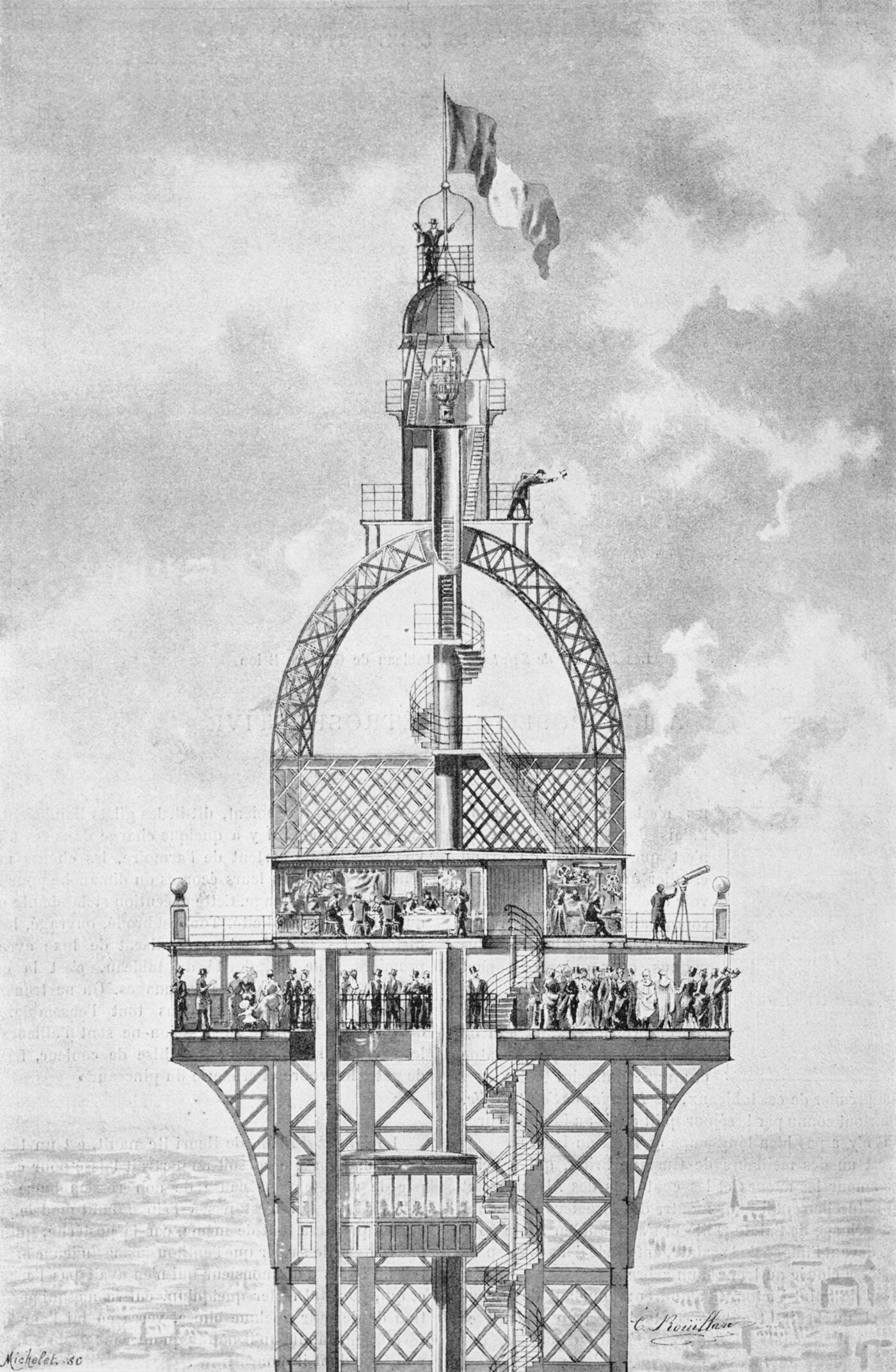

The Secret Apartment at the Top of the Eiffel Tower

Pictured above is an illustration of the Eiffel Tower’s original crown design. You can see the main observation deck, which is packed with people, all enjoying the view atop the tallest building in the world. Unbeknownst to them, however, is the private apartment located on the floor just above them. It was designed by and for Gustave Eiffel as a private space for himself to entertain notable guests and perform scientific experiments. It’s generally referred to as the secret apartment, but it was fairly well-known to the public that Eiffel built the space for himself.

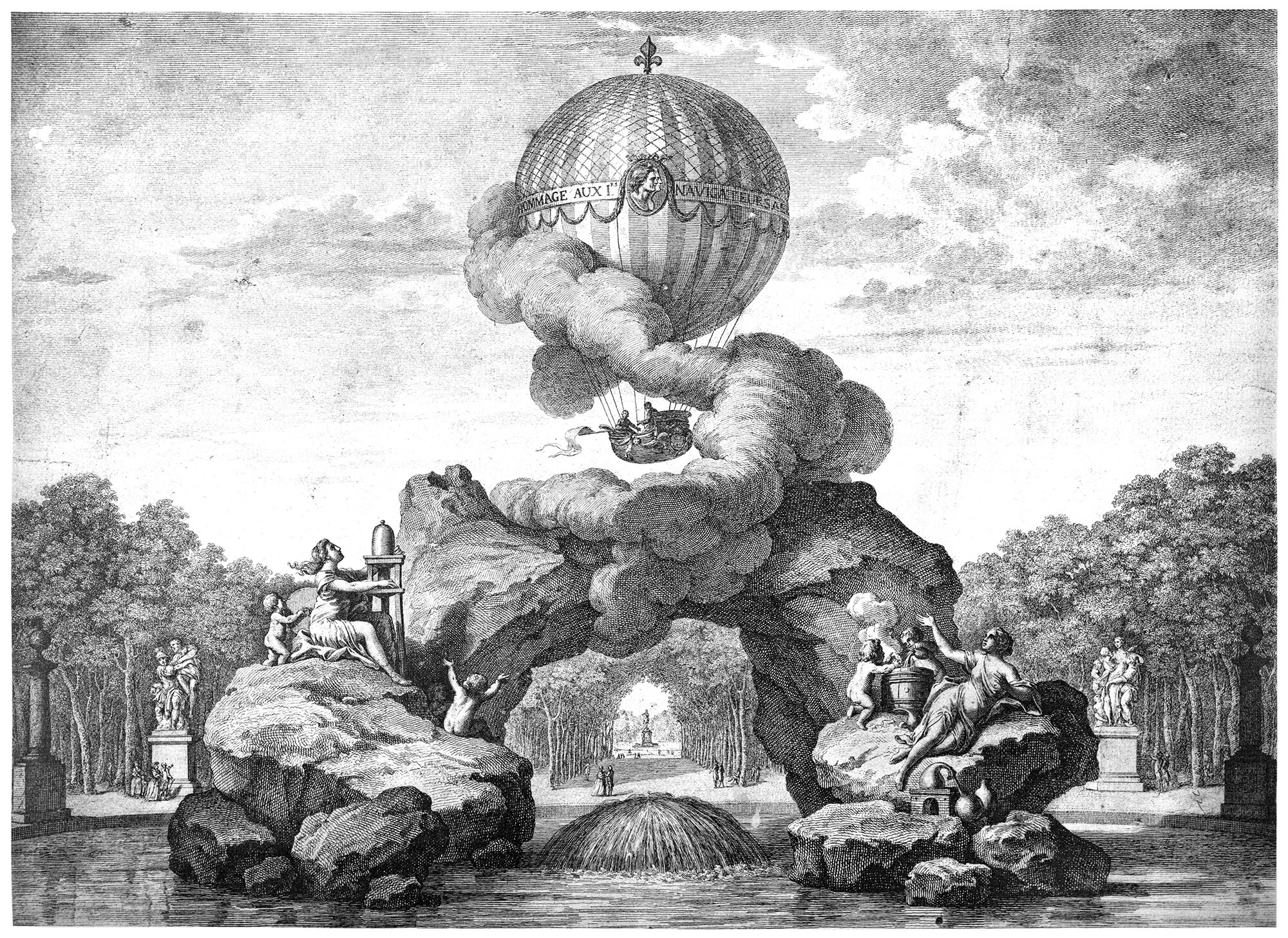

A Monument to the Glory of the First Aerial Navigators

Pictured above is the Projet d'un monument à la Gloire des Premiers Navigateurs Aériens, or the Monument to the Glory of the First Aerial Navigators. It was designed by an anonymous author for a site in the Tuileries Garden in Paris, and it consists of a stone arch placed in a fountain, with a balloon flying above it supported by a cloud-like form.

The Isolation of Flight

Have a look at the above illustration. It shows an airship high up in the clouds, isolated and alone up in the sky. This view encapsulates the idea that humans are surface-dwellers, and we’re not built for a life in the clouds. Throughout our history, we’ve spent untold amounts of time and energy trying to escape the surface of the earth, but the reality of such an escape is so foreign to our needs, that it creates a conflict within us.

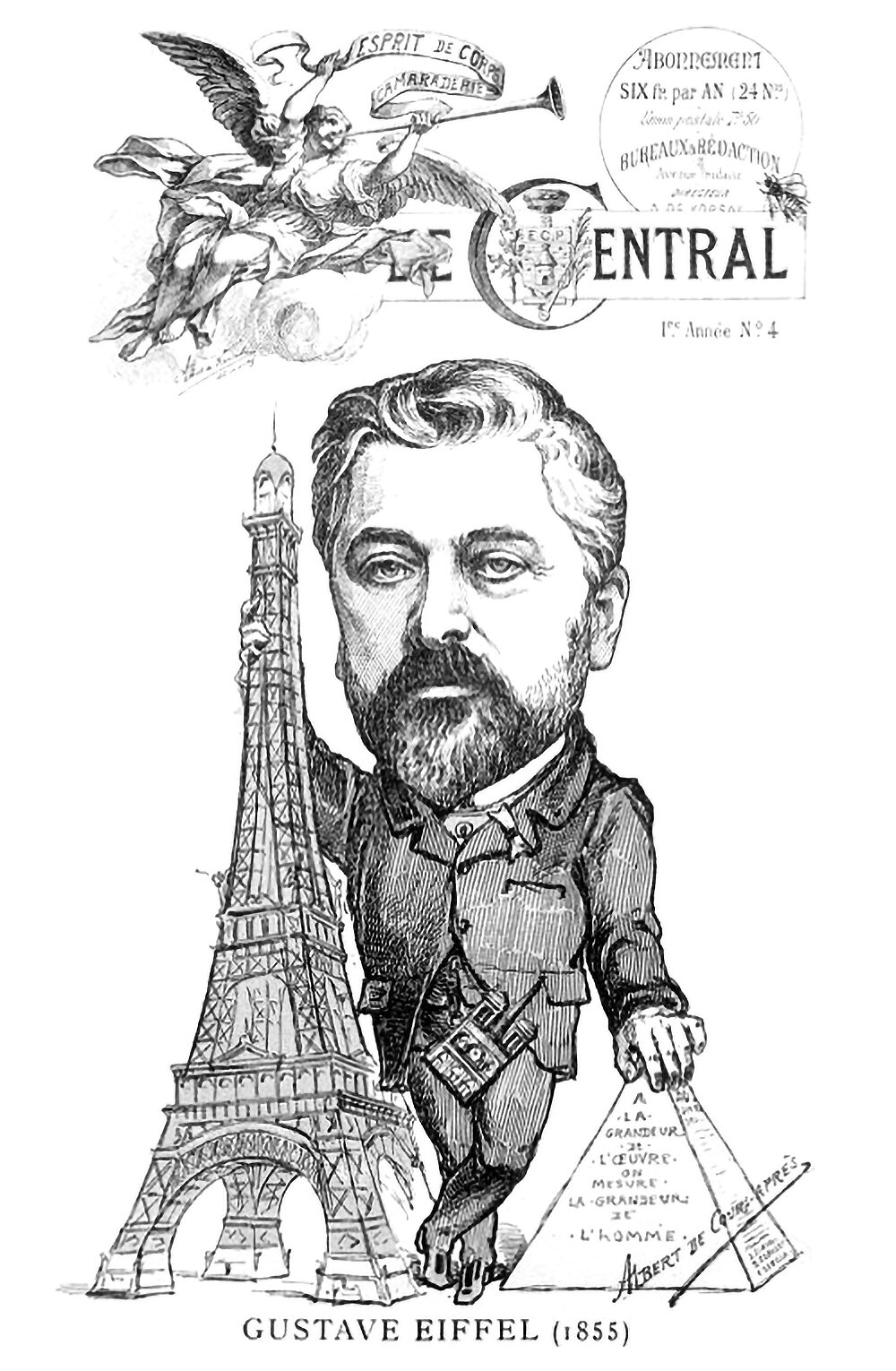

By the size of the work, we measure the size of man

The above illustration is from the cover of an 1889 issue of Le Central. It shows a caricature of Gustave Eiffel standing in between his Eiffel Tower and the Great Pyramid. Inscribed on the pyramid is the phrase A la grandeur de l'oeuvre on mesure la grandeur de l'homme, or By the size of the work we measure the size of man. It’s a statement on verticality, and it illustrates how the height of these structures is their defining characteristic in the eyes of the public.

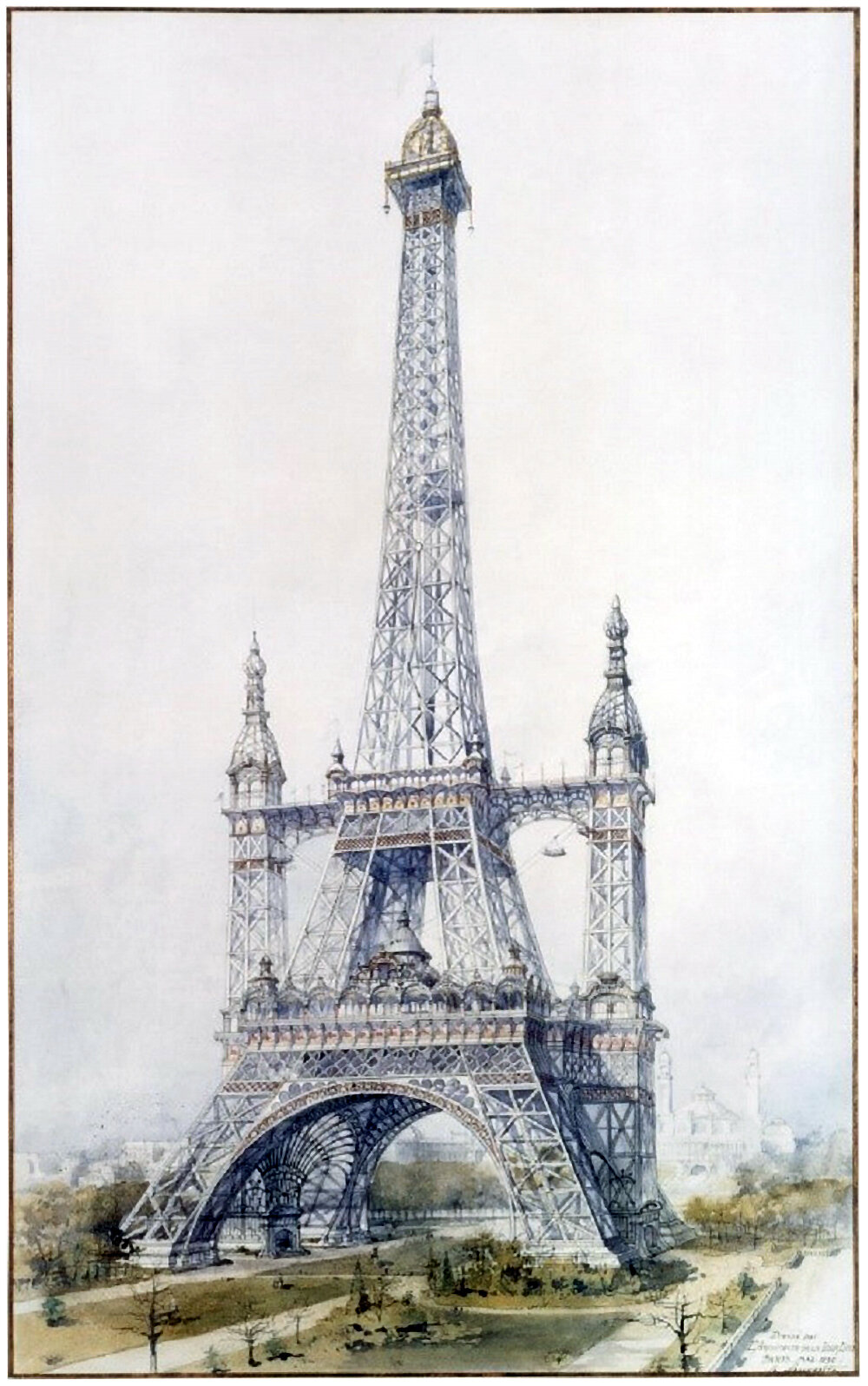

Alternate Realities : The Eiffel Tower

There’s an interesting subtext to unbuilt projects throughout the history of architecture. Unbuilt additions to existing buildings are the most intriguing, because they respond to an existing mind-scape rather than create a new one. The above illustration is a perfect example of this. It shows a preliminary design for the Eiffel Tower in Paris, drawn by French architect Stephen Sauvestre.

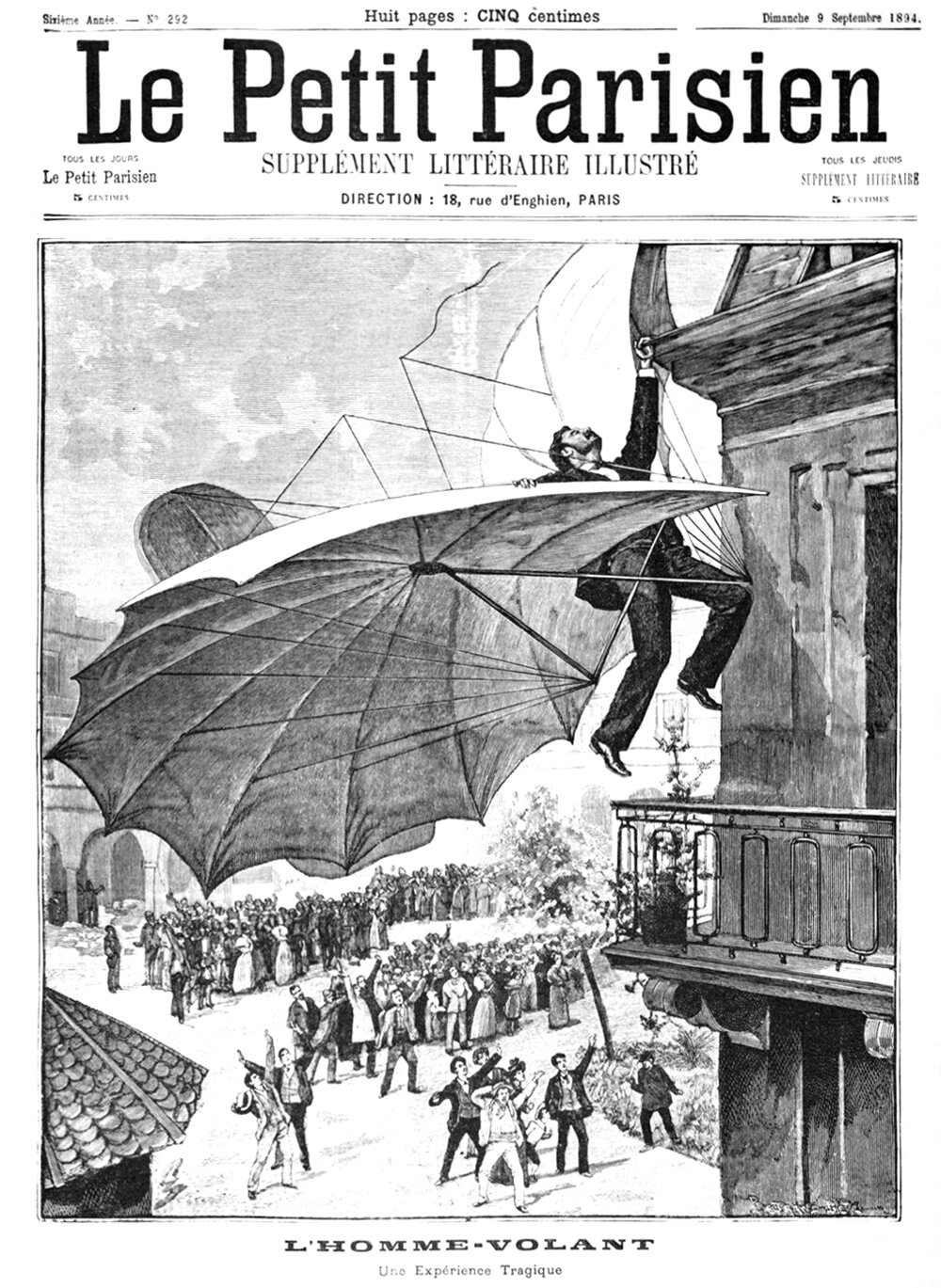

L’Homme Volant

Pictured above is the cover of Le Petit Parisien from 9 September 1894. It shows German aviation pioneer Otto Lilienthal dangling from a building cornice, with a crowd of onlookers below. According to the paper, the illustration was drawn from a photograph which was taken a few days earlier in Frankfurt, Germany.

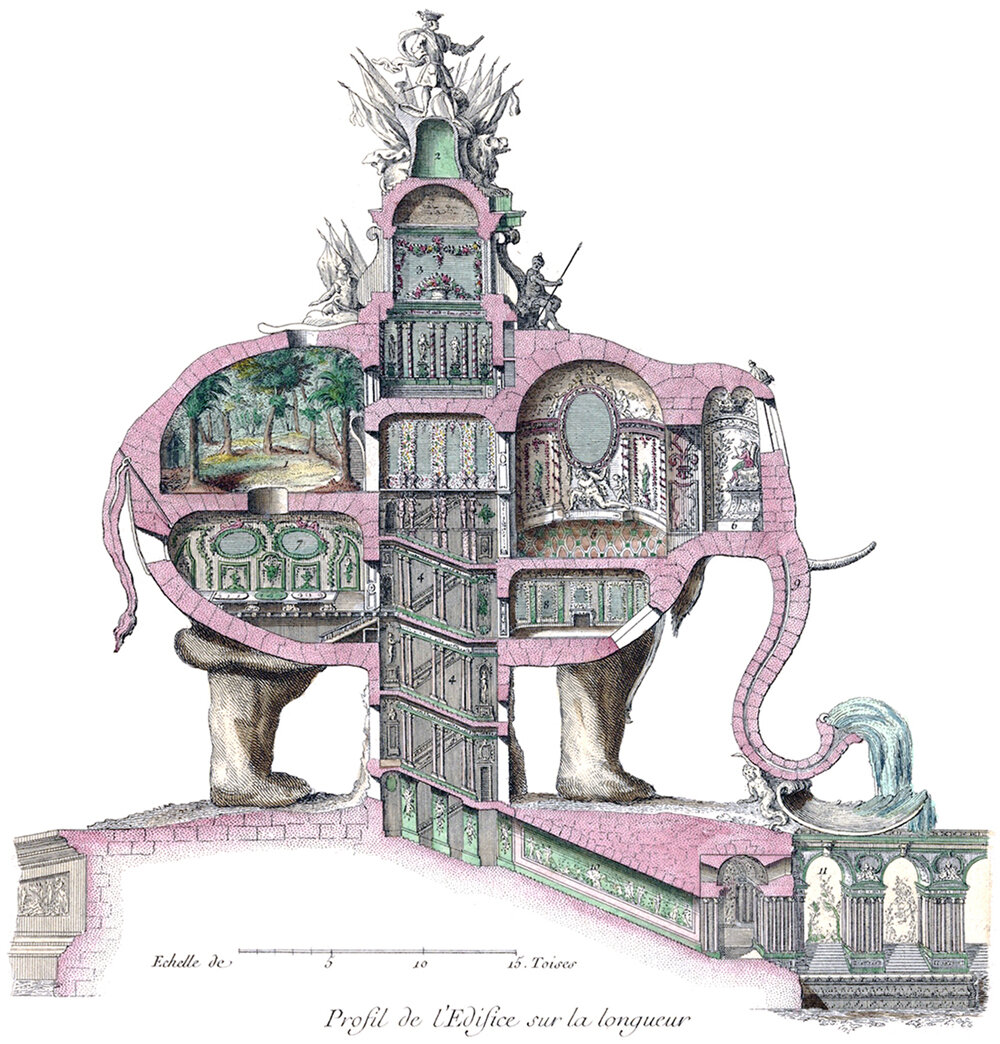

Charles Ribart’s Triumphal Elephant

Certain architectural proposals are hard to take seriously. This is one of them. It’s a design for the site that the Arc de Triomphe would eventually get built on in Paris, and it was proposed a few decades before the iconic monument broke ground. Yes, it’s a giant elephant. Yes, the architect was being serious. Yes, the French government swiftly rejected the proposal.

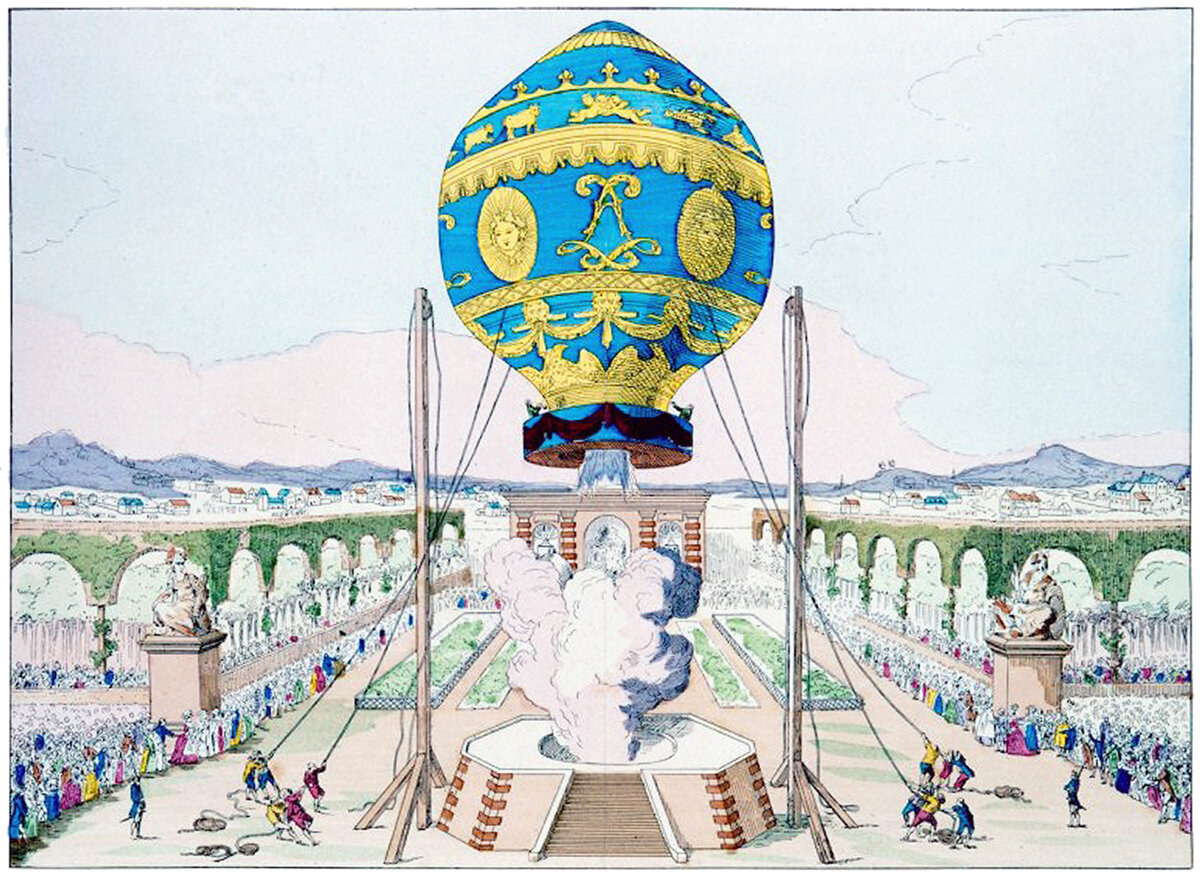

The Montgolfier Brothers and Their Balloons

The Montgolfier Brothers are credited with the first ever successful balloon flight with a human pilot. Pictured above, the flight took place in Paris in 1783. The brothers, Joseph-Michel and Jacques-Étienne, were born into a family of paper manufacturers, but became obsessed with flight after observing clothes drying over an open fire. Together, they subsequently experimented with flight and invented the Montgolfière-style hot-air balloon.

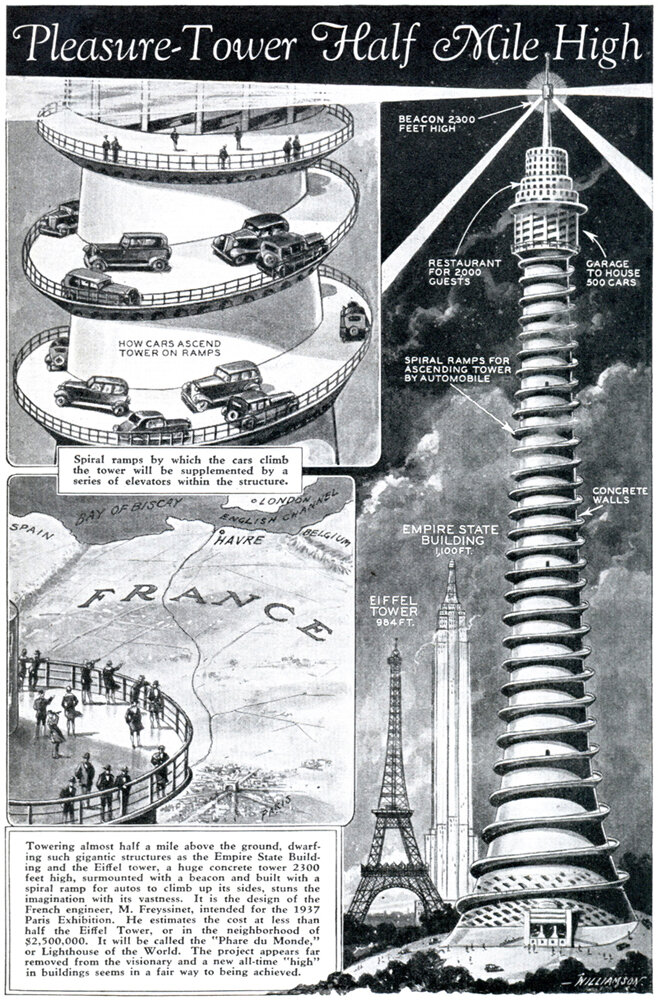

The Phare du Monde Pleasure Tower

Pictured above is a tower proposal from 1933 for the 1937 World’s Fair in Paris. It features an external spiral ramp leading to a parking garage 1640 feet (500 meters) from ground level.[2] Once at the top, visitors would find a restaurant, hotel and observation deck, and the spire contained a lighthouse beacon and a meteorological cabin. The view? Sublime. The design? Utterly ridiculous, unless taken as a satirical statement on civilization’s reliance on the automobile.

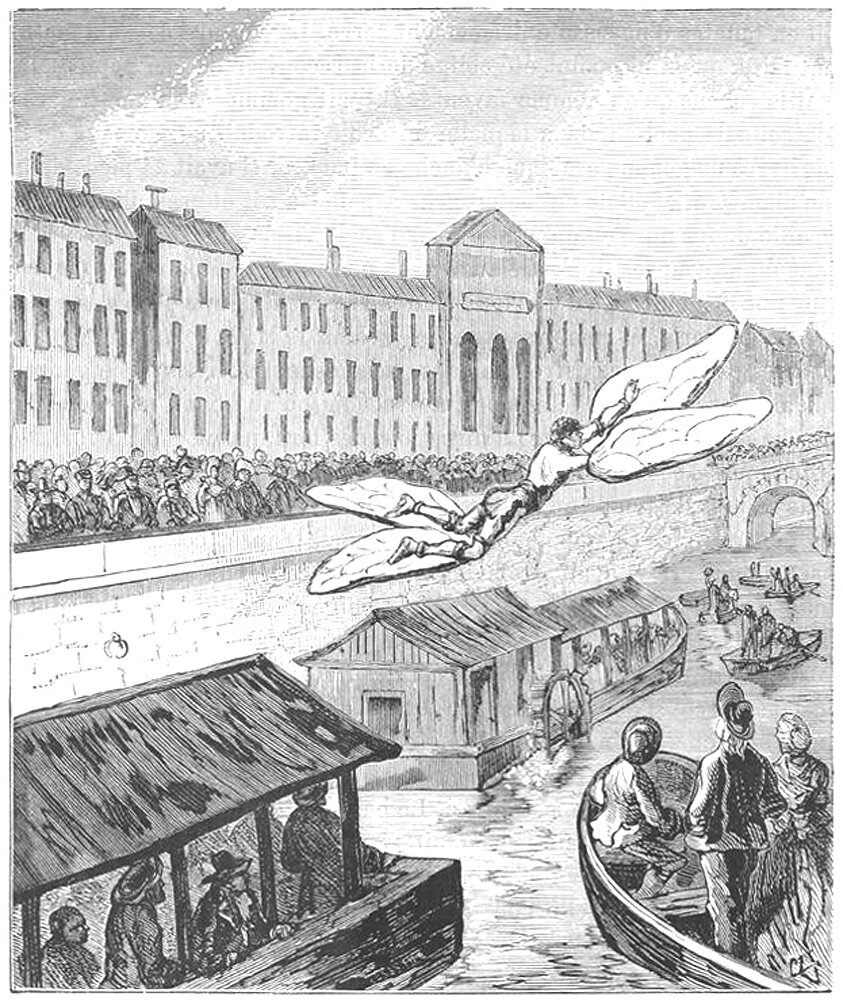

Marques de Bacqueville's Leap of Faith

Pictured above is Marquis de Bacqueville, an eccentric French nobleman best known for his attempt at human flight in 1742. His full name was Jean-François Boyvin de Bonnetot, and he was born in Rouen in 1688. Details about his attempted flight are varied, but apparently on March 19, 1742 in Paris, de Bacqueville announced his intention to fly from one side of the river Seines to the other.

Verticality, Part X: Conquering The Skies

The construction of the Equitable Building in 1915 ushered in a new age of skyscraper design. Humans were now able to escape the surface of the Earth with our interior environments, and our need for Verticality had ceased to be driven by the unknown. It was now driven by our need to congregate through density and to distinguish ourselves from one-another. Ego had replaced God, and as a result our quest for Verticality would become synonymous with human achievement.