Welcome to On Verticality. This blog explores the innate human need to escape the surface of the earth, and our struggles to do so throughout history. If you’re new here, a good place to start is the Theory of Verticality section or the Introduction to Verticality. If you want to receive updates on what’s new with the blog, you can use the Subscribe page to sign up. Thanks for visiting!

Click to filter posts by the three main subjects for the blog : Architecture, Flight and Mountains.

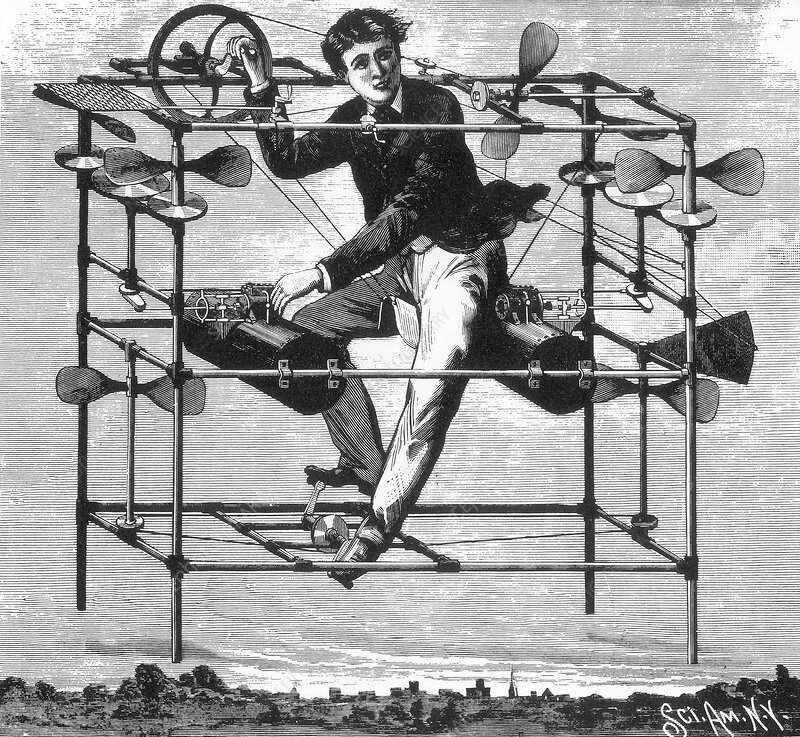

Jakob Degen’s Flugmaschine

This is Jakob Degen’s design for his Flugmaschine, an ornithopter that was meant to fly with the power of human muscles. Degen was a Swiss watchmaker who became interested in human flight in the early 1800’s. He designed the first prototype of his Flugmaschine in 1807, which is pictured above. It was rather simple to operate; the pilot would stand on a rigid metal frame and move a horizontal bar up and down in order to flap the wings.

The Ancient Chullpa of Peru

Where do we go after we die? This question has been on our minds since pre-history, and we’ve come up with myriad stories and strategies to address it. Pictured above is an ancient chullpa, which is an ancient, above-ground tomb built by the Aymara people in Peru and Bolivia. The Aymara were an indigenous people who became a subject people of the Inca in the 15th and 16th century.

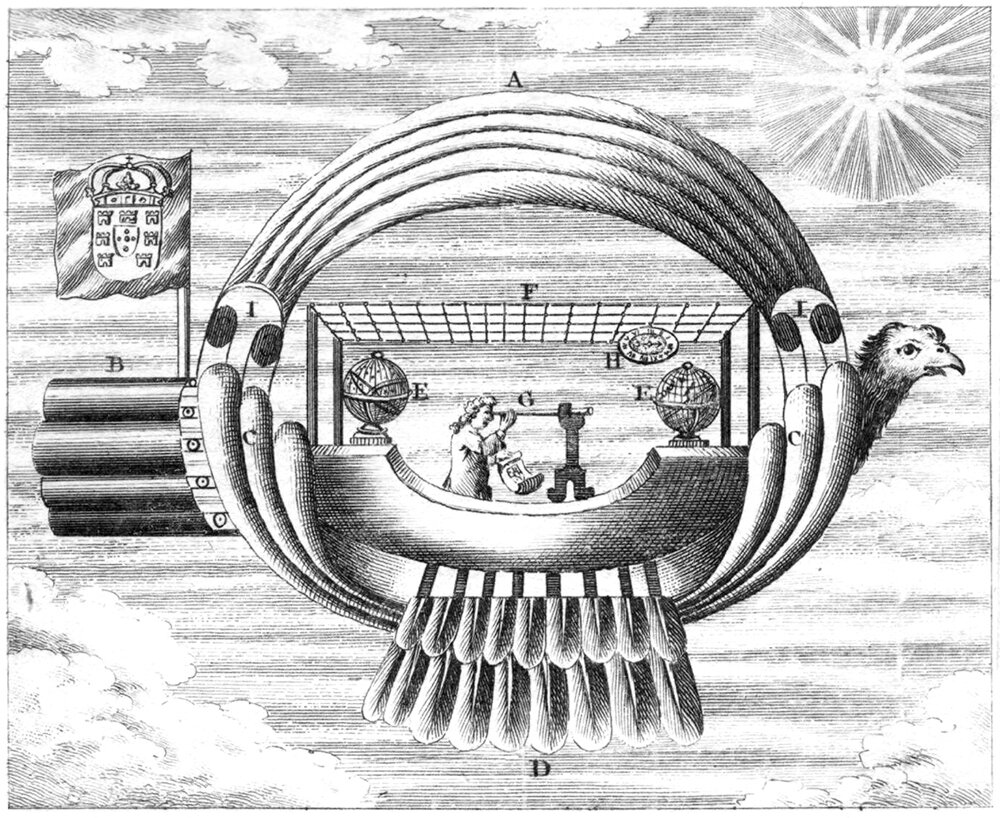

Bartolomeu de Gusmão's Passarola Airship

Many of the oldest ideas for flying machines imitated birds in some way. This proposal, by Brazilian-born Portugese inventor Bartolomeu de Gusmão, fits squarely into this category. His flying machine, called Passarola, translates to bird in Portugese. Gusmão was building on the ideas of Francesco Lana de Terzi, who previously drew up plans for a flying ship, complete with sails and a hull.

Francesco Lana de Terzi's Aerial Ship

Francesco Lana de Terzi is sometimes referred to as the Father of Aeronautics. He was an Italian Jesuit priest, a professor of physics and mathematics, and he was intrigued with human flight. In 1670 he published Prodromo, a book containing myriad ideas and inventions, the most famous of which was the design for a flying ship.

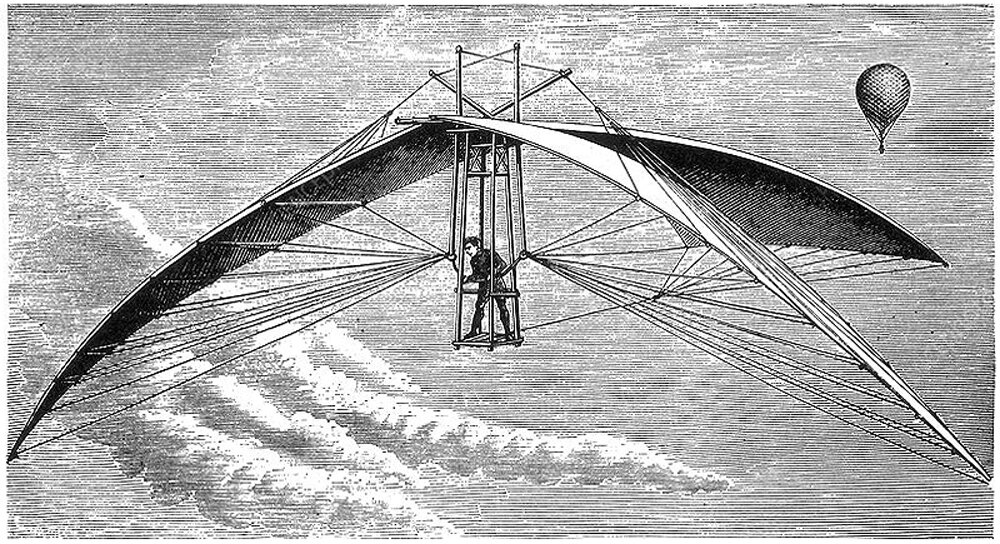

Vincent de Groof's Ornithopter

This is Vincent de Groof’s design for an ornithopter, built and tested in Bruges and London in the 1870’s. Details about de Groof’s life are sketchy, and newspaper articles from his day tend to contradict themselves. One consistent fact is that he was called The Flying Man. His goal was to achieve flight, and he believed it was possible for a human to fly by imitating the flight of a bird.

"Space isn't remote at all. It's only an hour's drive away if your car could go straight upwards."

-Fred Hoyle, British astronomer, 1915-2001

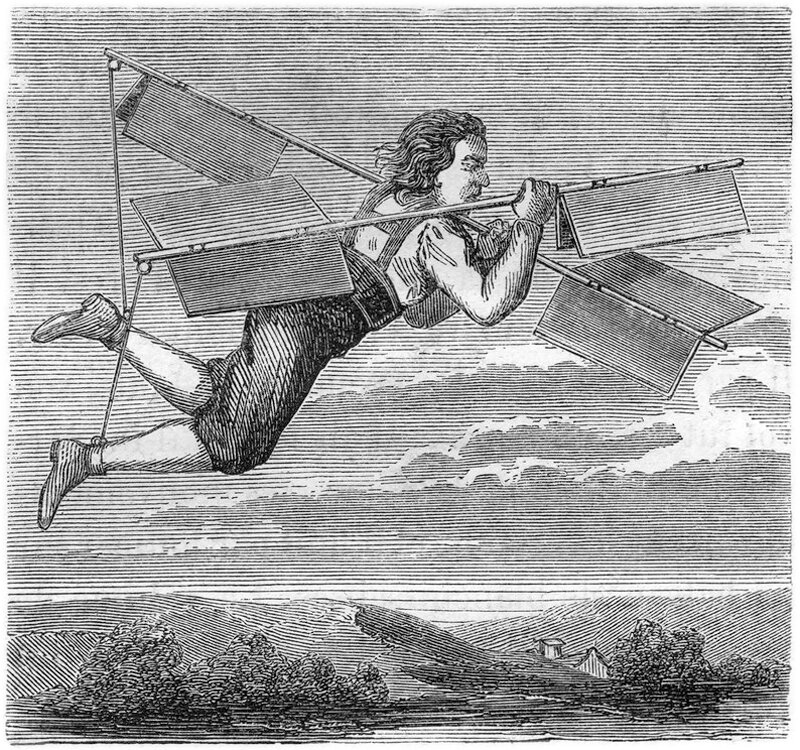

Besnier's Flying Apparatus

Many early attempts at flight were taken by people who had no formal background in the subject. Pictured above is Besnier, a locksmith from Sablé, France. In the 1670’s, Besnier had become obsessed with flight, and sometime around 1678 he built and tested an apparatus to mimic the beating of a bird’s wings.

The Tallest Building in The South

To hell with context. The artist behind the postcard above must have been thinking something similar when conjuring up the fantasy that was to be The tallest building in the South. I use the term artist, rather than architect or designer, because the building depicted hasn’t been designed, but rather imagined. It’s a non-functional idea for a tall building, rather than an actual building proposal.

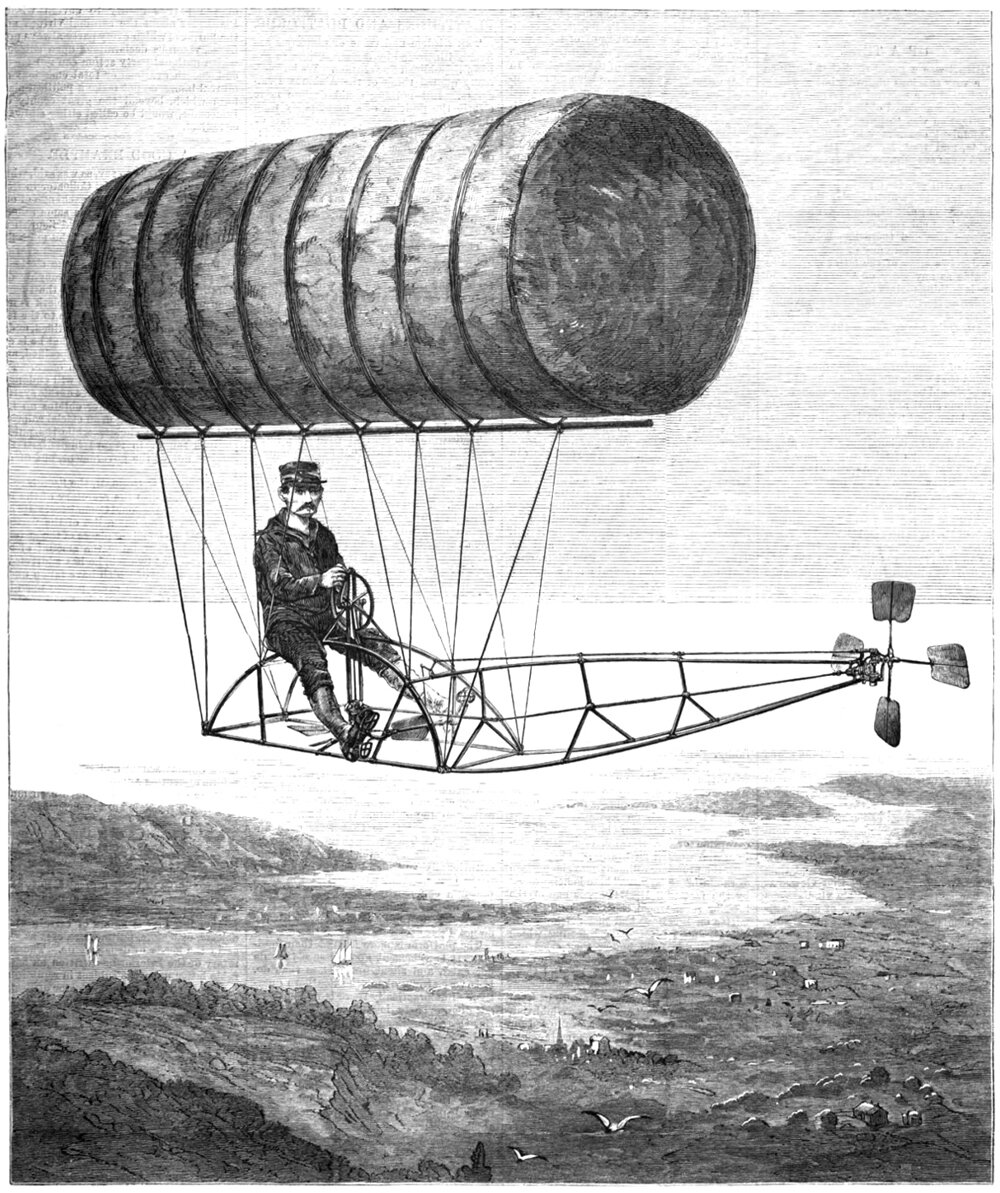

Charles F. Ritchel's Dirigicycle

This is the cover of Harper’s Weekly from July 13th, 1878. The issue featured an etching of a man sitting on a tubular frame, suspended high in the air by what looks like an elongated bail of hay. The man pictured is Charles F. Ritchel, and he’s piloting his design for a dirigible. A dirigible is an airship capable of being steered (it comes from the Latin word dirigere, which means ‘to direct’), and the bail of hay is in fact a bag of rubberized fabric called ‘gossamer cloth’, filled with hydrogen gas.

William O. Ayres' Aerial Machine

There have been myriad ideas and inventions for flying machines over the years, and this one caught my eye for various reasons. It’s a design by William Orville Ayers from 1885, and it’s called the New Flying Machine. Ayers was a physician who was interested in the natural sciences, particularly ornithology (the study of birds). This interest in birds no doubt expanded to flight, and ultimately led to the design for a flying machine pictured above.

Liftoff and the Freedom of Flight

Flight has captivated humanity since pre-history. The space above our heads represents freedom, and flying through it represents an escape from our surface-based lives. To fly is to break free of the shackles of a surface-based existence and achieve a higher level of being.

"The desire to fly is an idea handed down to us by our ancestors who ... looked enviously on the birds soaring freely through space ... on the infinite highway of the air."

-Wilbur Wright, inventor and aviation pioneer, 1867-1912

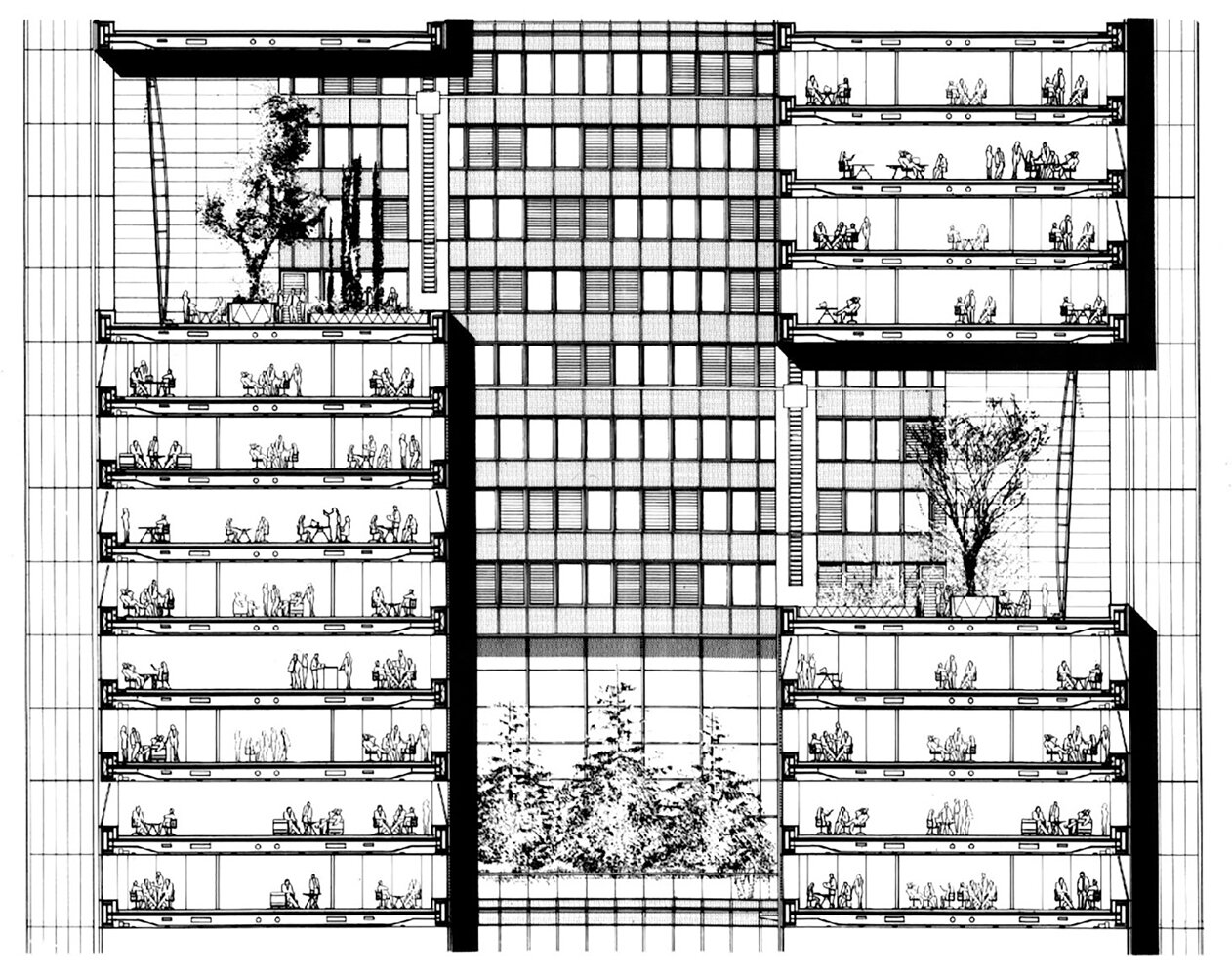

Verticality, Part XI: Breaking the Box

A rebellion against spacecraft and efforts to humanize the tall building

The human experience of stacked, identical floors on top of one another was foreign to our surface-dwelling nature. The disconnected, isolated experience of International Style buildings took us up to the sky, but cut us off from everything surrounding us. This lack of variety in tower floors and the monotony of box-like tower forms would begin to be challenged by architects. This signaled that we needed to humanize our experience of Verticality again. Instead of monotonous boxes, towers began to see their forms eroded away in order to create more varied experiences within them. We needed to recreate the surface in the sky.

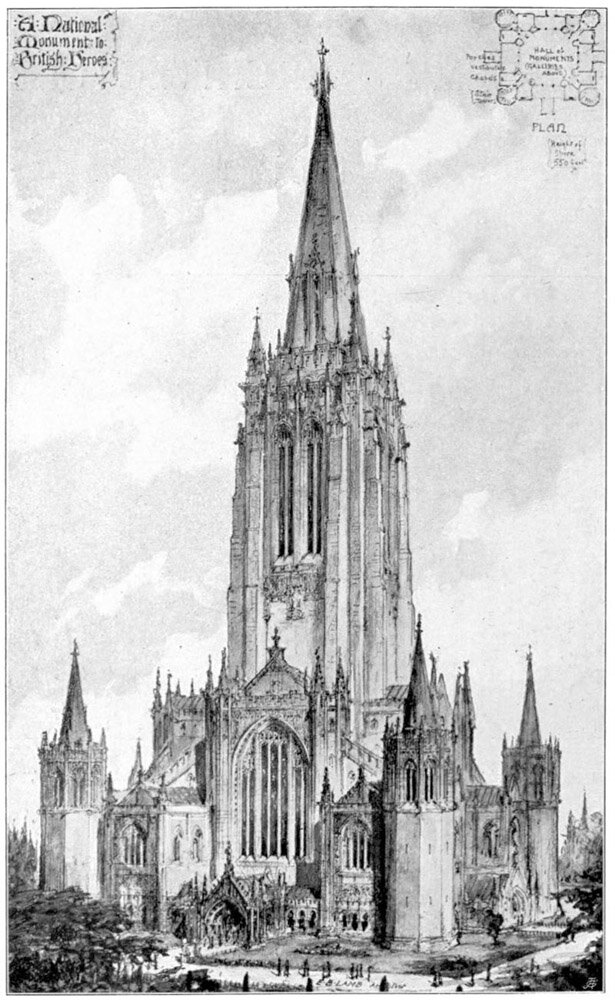

Edward B. Lamb's Monument to British Heroes

This is the National Monument to British Heroes, proposed by Edward B. Lamb in 1901. The structure was meant to house a hall of monuments and galleries, presumably to honor those who had died for the British crown throughout history. The proposal consists of a massive central belfry topped with a steeple and flanked by four turrets at its base.

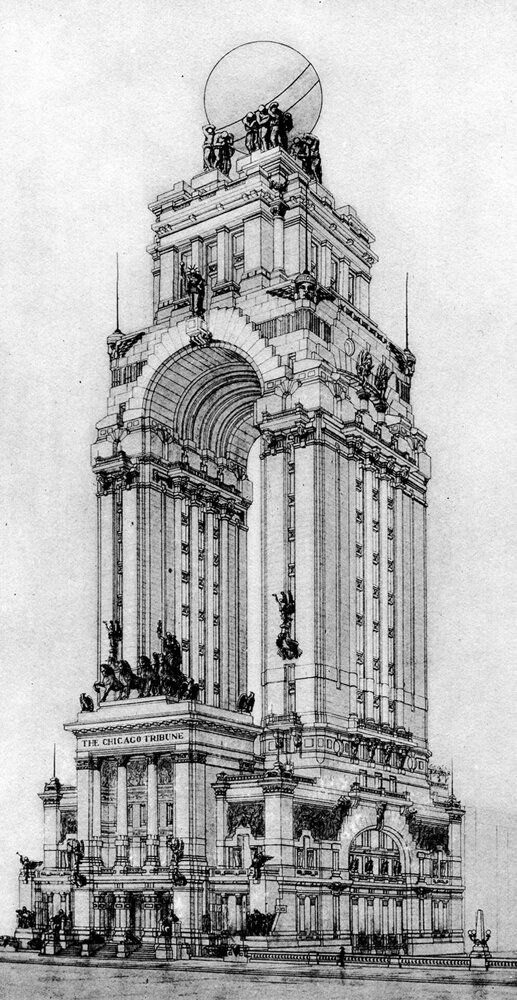

Saverio Dioguardi's Tribune Tower Proposal

Every time I research the Chicago Tribune Tower competition, I run into this proposal by Italian architect Saverio Dioguardi. His design is wonderfully flamboyant, and it’s more of a monument than a building. There’s something eye-catching about the sheer audacity of it, however, which is why I’ve singled it out here.

"For my part I know nothing with any certainty, but the sight of the stars makes me dream."

-Vincent van Gogh, Dutch impressionist painter, 1853-1890

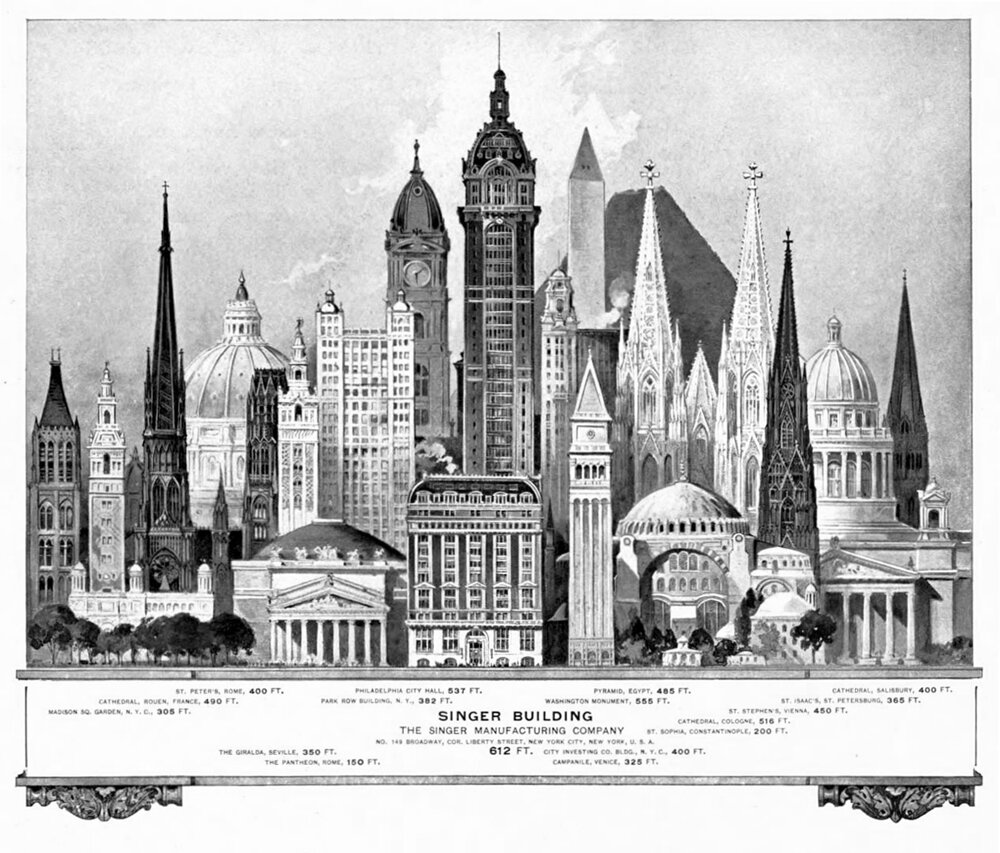

Height Lineups and the Abstraction of Verticality

Height lineups like this serve to illustrate how important Verticality is to the perception of our tall buildings, and studying this example got me intrigued about the nature of drawings like this. After some digging, I found many more examples of height lineups throughout the past two centuries, and there are curious commonalities throughout all of them. For starters, they are just beautiful drawings to study. On a deeper level, they provide us with a window into the perceived importance of buildings during a given time in history.

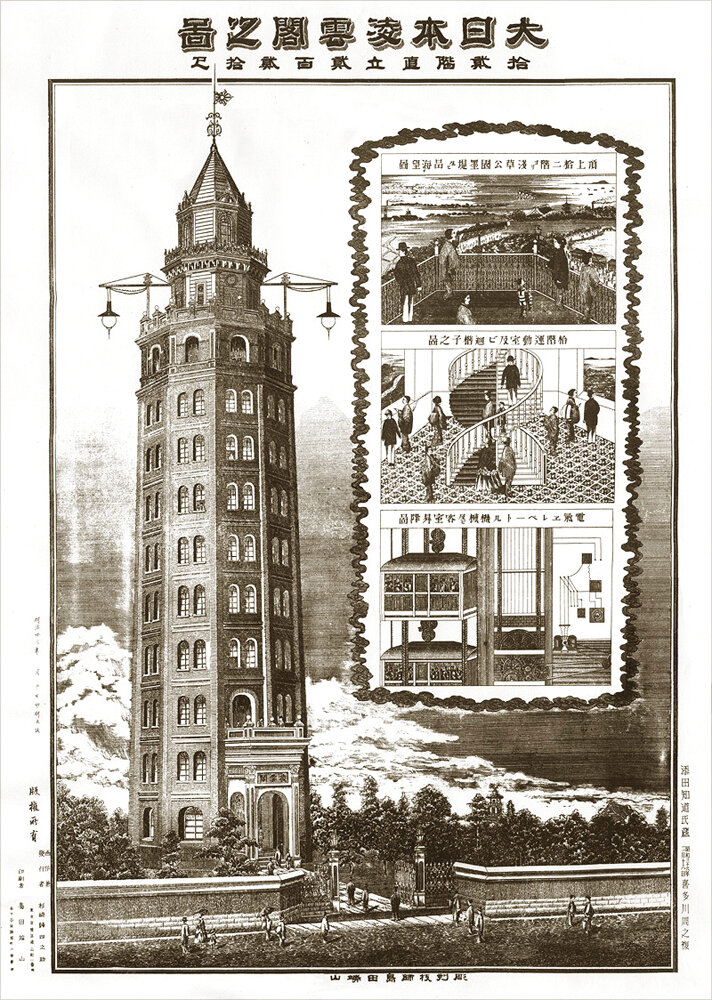

Ryōunkaku Tower: Japan's First Skyscraper

This is Ryōunkaku, Japan’s first western-style skyscraper. Built in 1890 in the Asakusa district of Tokyo, Ryōunkaku resembles a lighthouse, with an octagonal plan and a slight taper, topped with two setbacks and a pointed roof. The name Ryōunkaku translates to Cloud-Surpassing Tower, which indicates the importance of Verticality for the building’s landmark status.

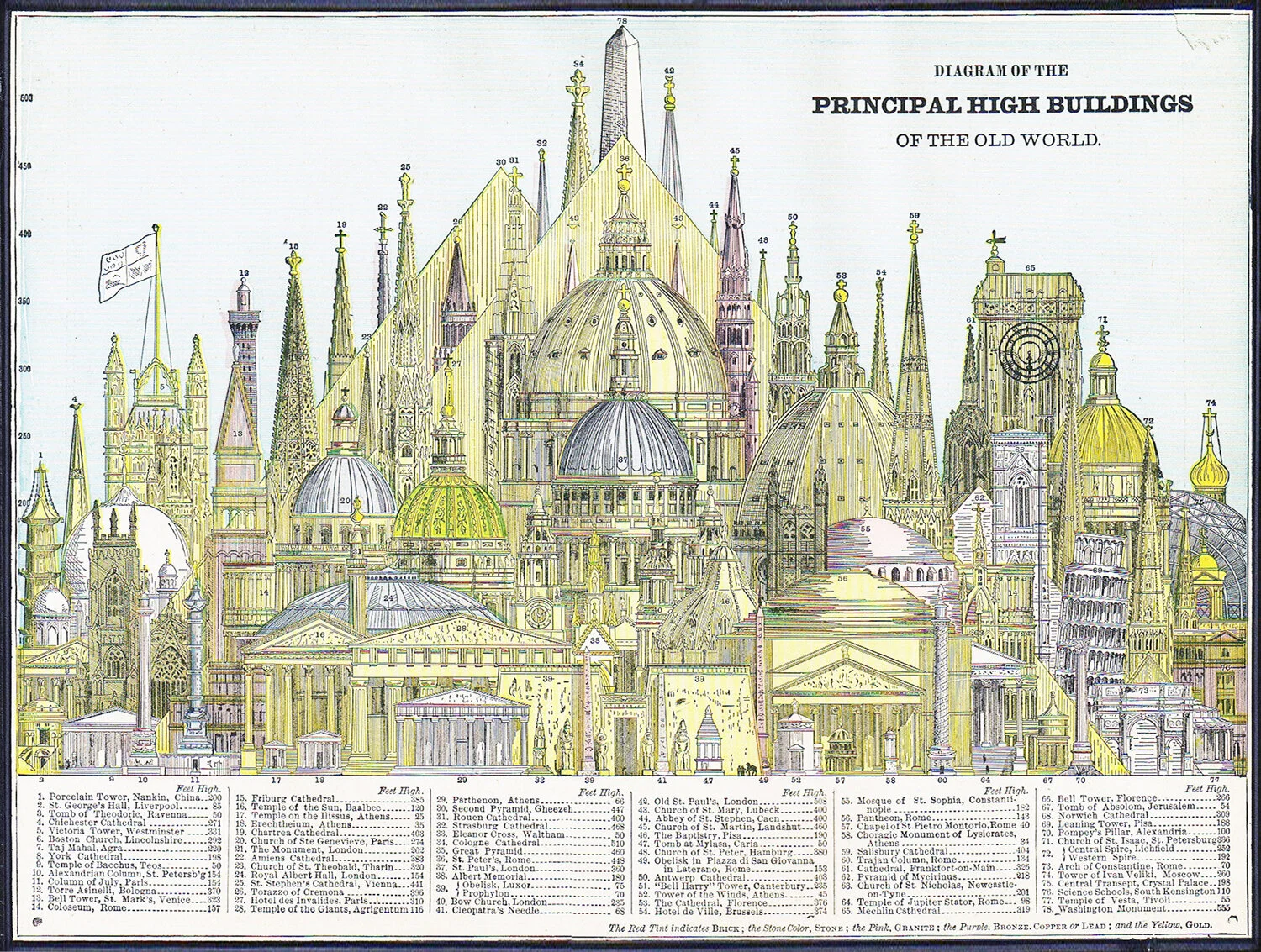

Domes and Steeples of the Old World

This drawing is from an 1884 issue of Cram's Unrivaled Family Atlas of the World, and it depicts the Principal High Buildings of the Old World. What’s striking about the composition is how many domes and steeples are featured. Aside from the hulking pyramids in the middle ground, there is a forest of slender steeples running along the background, along with a bunch of bulky domes that dominate the middle of the diagram. Steeples and domes were our most popular methods for achieving Verticality throughout history, with each form pushing up towards the sky and announcing its presence, and therefore importance, to the surrounding landscape.

Verticality, Part X: Conquering The Skies

The construction of the Equitable Building in 1915 ushered in a new age of skyscraper design. Humans were now able to escape the surface of the Earth with our interior environments, and our need for Verticality had ceased to be driven by the unknown. It was now driven by our need to congregate through density and to distinguish ourselves from one-another. Ego had replaced God, and as a result our quest for Verticality would become synonymous with human achievement.