Welcome to On Verticality. This blog explores the innate human need to escape the surface of the earth, and our struggles to do so throughout history. If you’re new here, a good place to start is the Theory of Verticality section or the Introduction to Verticality. If you want to receive updates on what’s new with the blog, you can use the Subscribe page to sign up. Thanks for visiting!

Click to filter posts by the three main subjects for the blog : Architecture, Flight and Mountains.

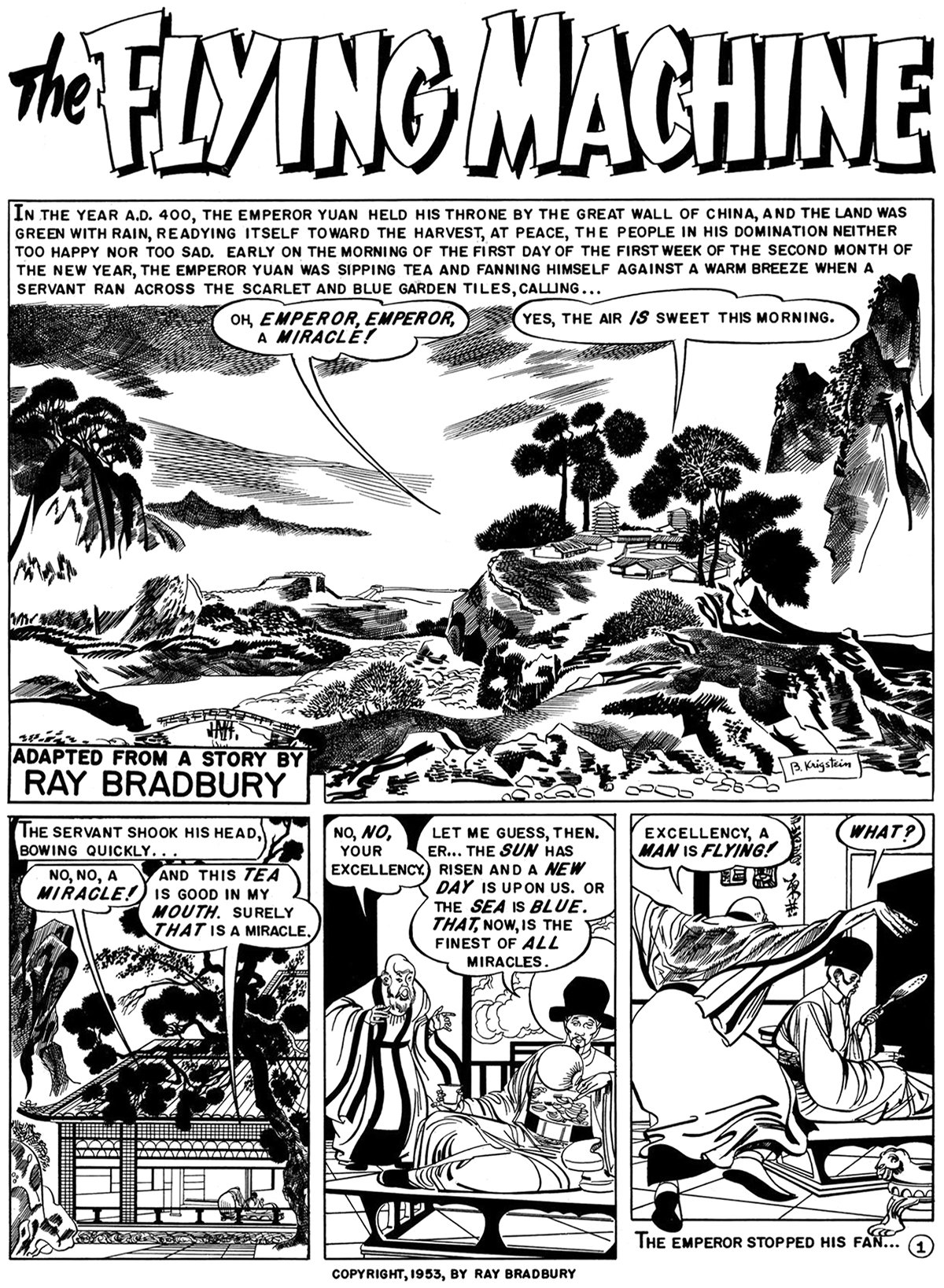

“I have found beauty … I have soared, like a bird. Oh, I cannot say how beautiful it is up there, in the sky, with the wind about me, blowing me like a feather.”

-Written by Ray Bradbury, American author, 1920-2012.

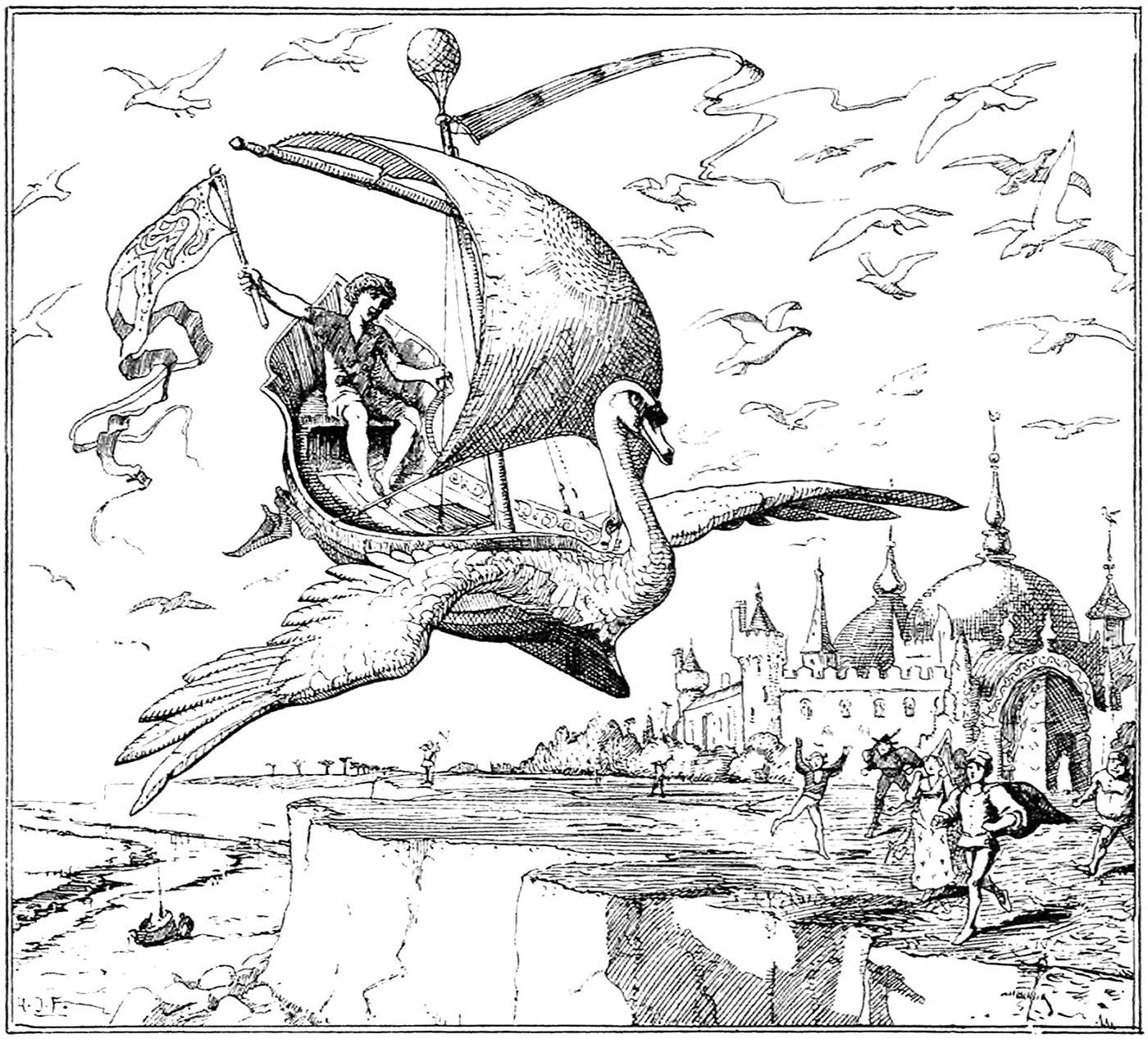

The Fool of the World and the Flying Ship

Flight is used in myriad folk tales to symbolize power. This is typically done to aid a character who is either downtrodden or has done a good deed without a promise of reward. The Russian folk tale The Fool of the World and the Flying Ship follows this pattern. It’s the story of a young fool who ends up marrying a princess because of a series of fortunate events, combined with his good-natured approach to others.

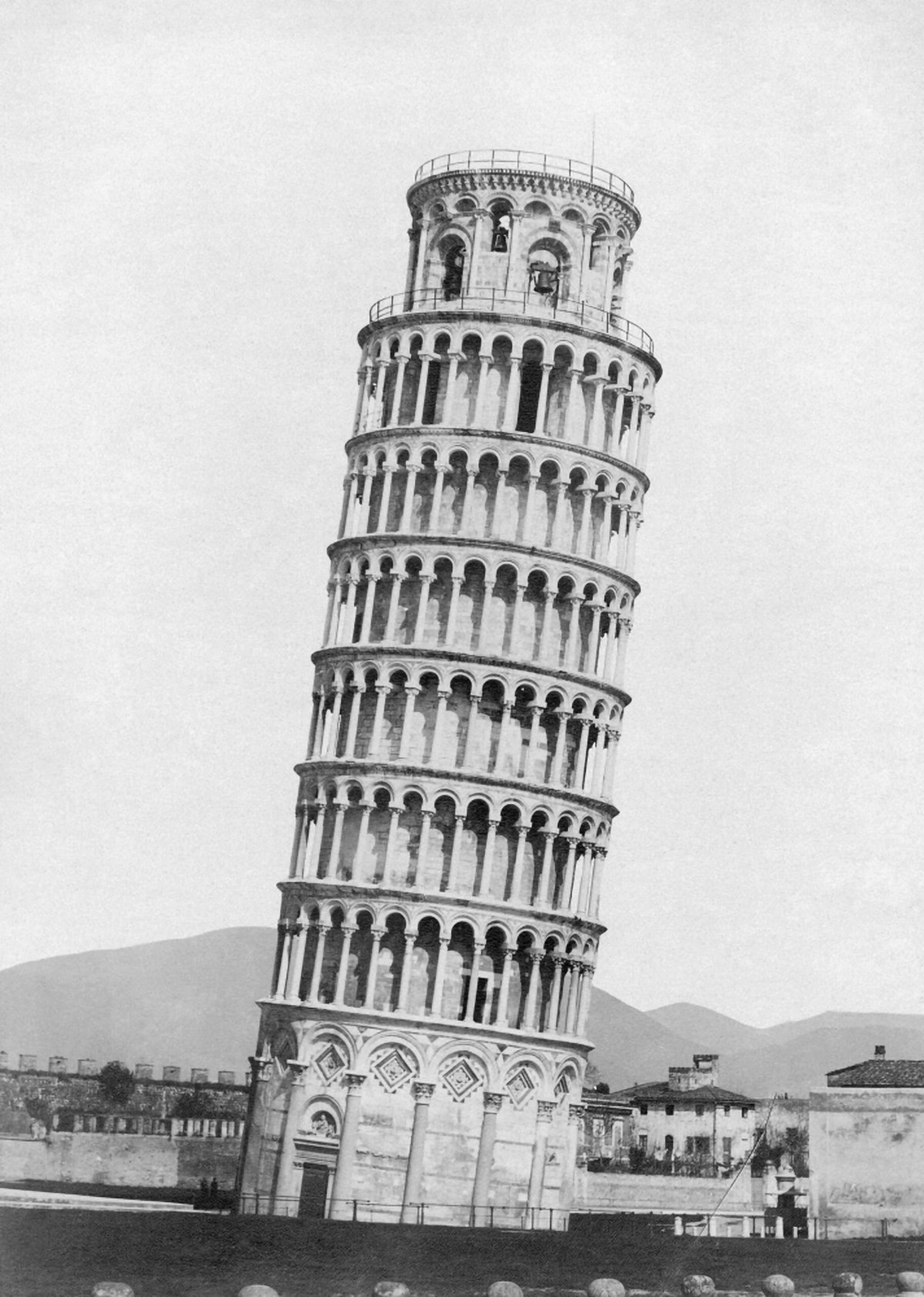

The Leaning Tower of Pisa and the Axis Mundi

Pictured here is the campanile at the Pisa Cathedral, known worldwide as the Leaning Tower of Pisa. The tower is world-famous for its iconic four-degree lean, and has become a major tourist attraction for the town of Pisa. This lean has allowed the campanile to become a symbol of the city. If you think of Pisa, you think of the Leaning Tower. This status and appeal comes from the campanile’s lack of vertical equilibrium, which forces visitors to confront the axis-mundi. It’s a unique tension that’s rooted in verticality.

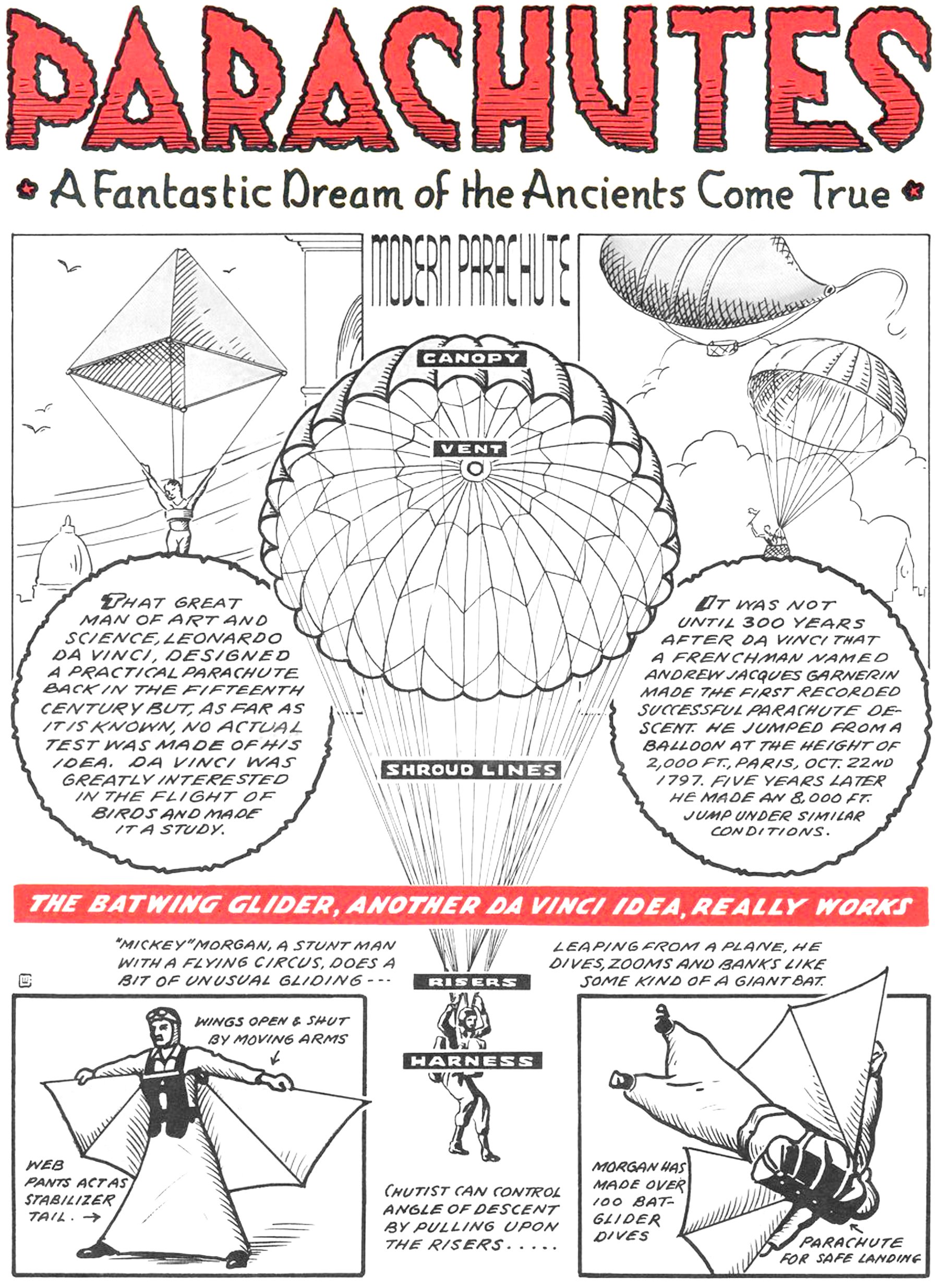

Parachutes : A Fantastic Dream of the Ancients Come True

Pictured above is a page from a War Heroes comic book from 1943. It features a few examples of parachutes and a flying suit called the Batwing Glider. At the center of the page is a modern parachute, complete with its canopy, vent, shroud lines, risers and harness. Flanking this drawing are two historical examples of parachutes. The first is a sketch from Leonardo da Vinci’s notebooks circa 1495, and the second is the world’s first successful parachute descent by André-Jacques Garnerin in 1797. This triad presents a concise, albeit incomplete history of parachute design, but it does do a good job of visually connecting a modern parachute to its ancestors.

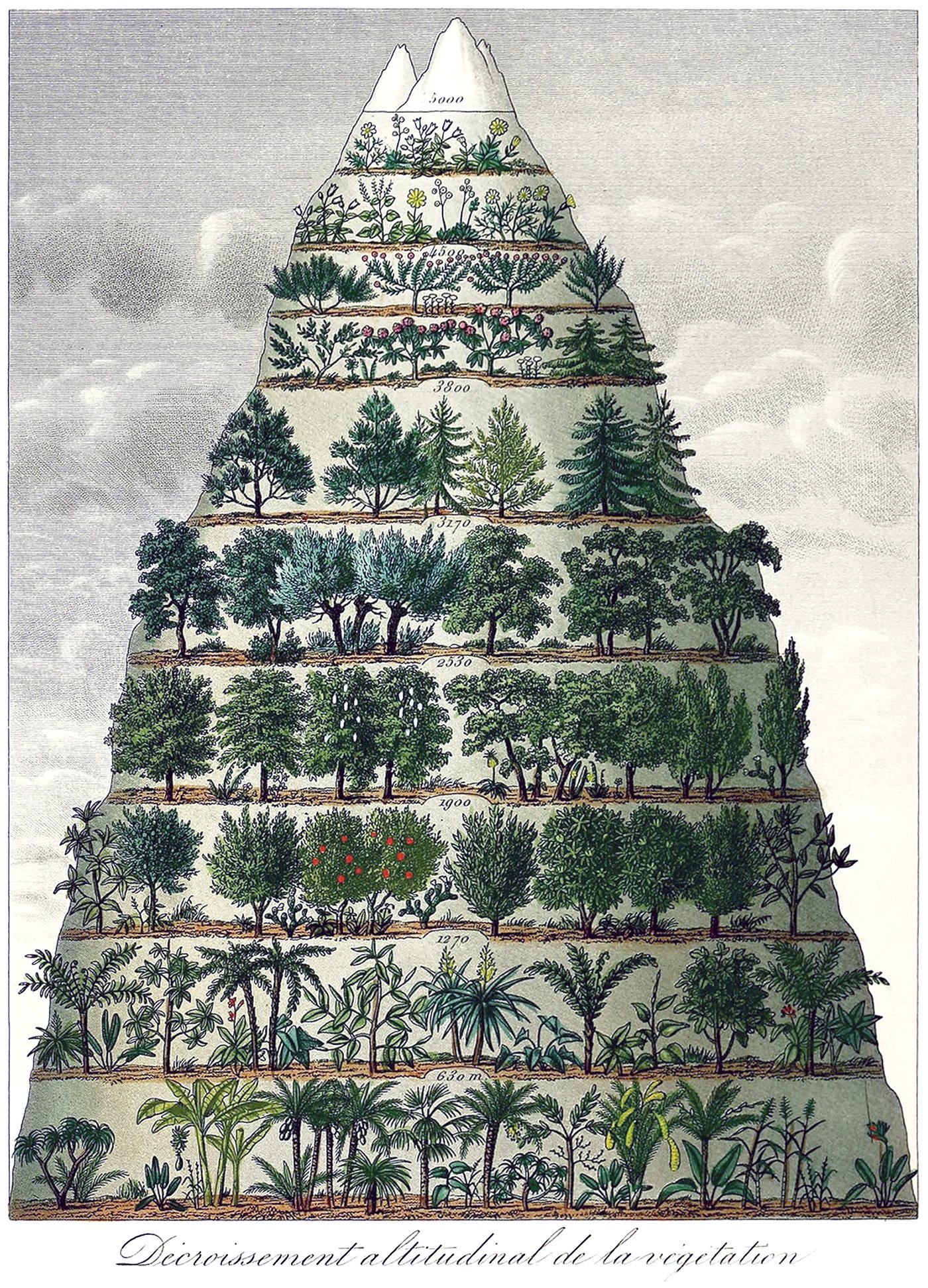

The Altitudinal Decrease in Vegetation

Pictured above is an illustration from the 1860s by Jean-Augustin Barral, titled Décroissement Altitudinal de la Végétation, which is French for The Altitudinal Decrease in Vegetation. It’s a beautiful work that attempts to categorize vegetation types by elevation, which is known as altitudinal zonation. Barral gets the overall concept correct, but we now know the details to be much more nuanced and complex than his drawing suggests.

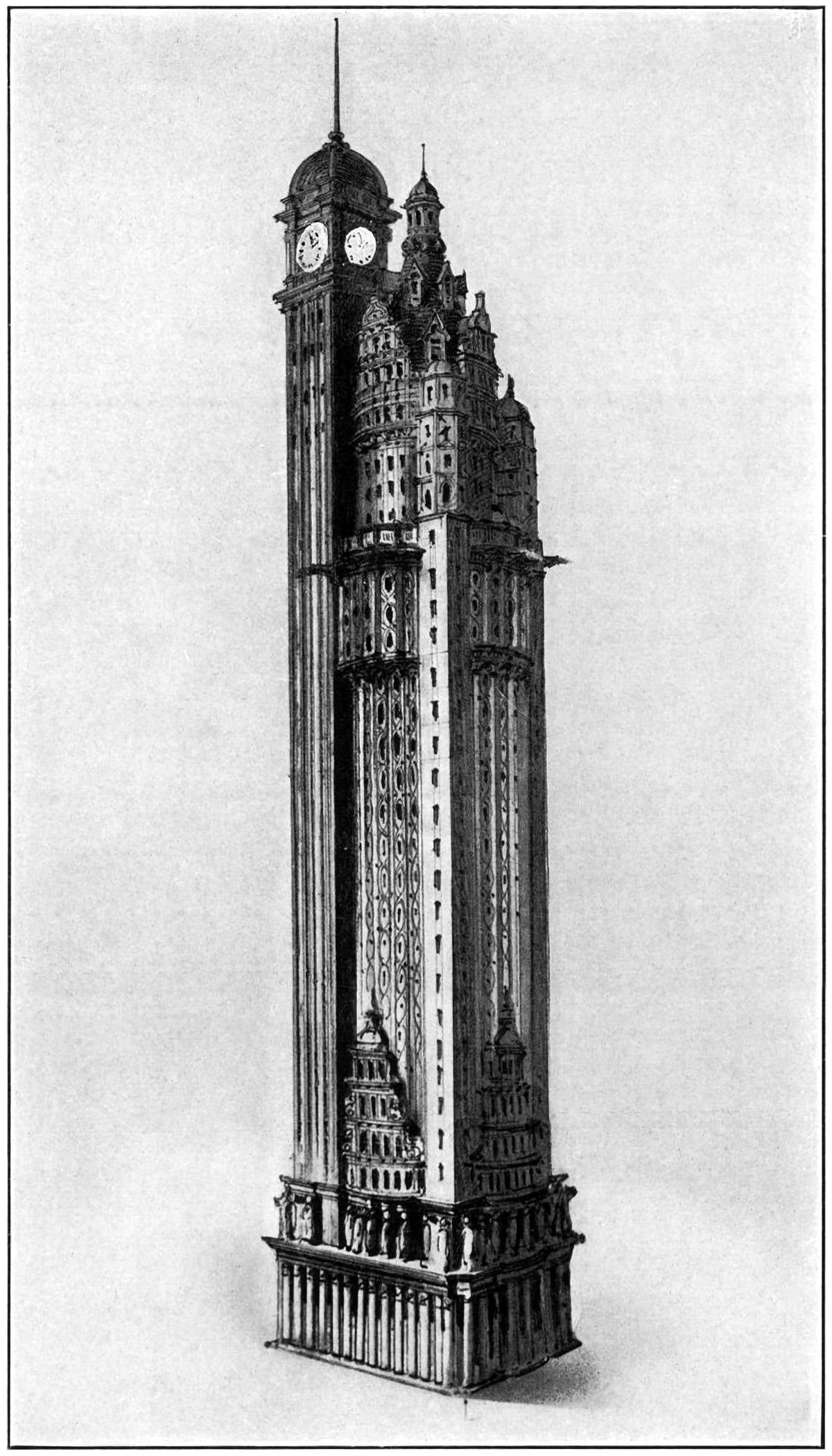

Constant-Désiré Despradelle’s Beacon of Progress

He was possessed by the idea of a monument embodying the characteristics of American civilization, to be a memorial to the genius of the American people and a reminder of the glories of the Columbian Exposition in Jackson Park. These words describe the feeling of Constant-Désiré Despradelle after he visited the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893 in Chicago. The exposition saw an entire complex of temporary buildings built in Jackson Park, only to be demolished after the fair. For Despradelle, Chicago needed a permanent monument to embody the spirit and grandeur of the fair. He set to work designing his vision, and the final result is pictured above.

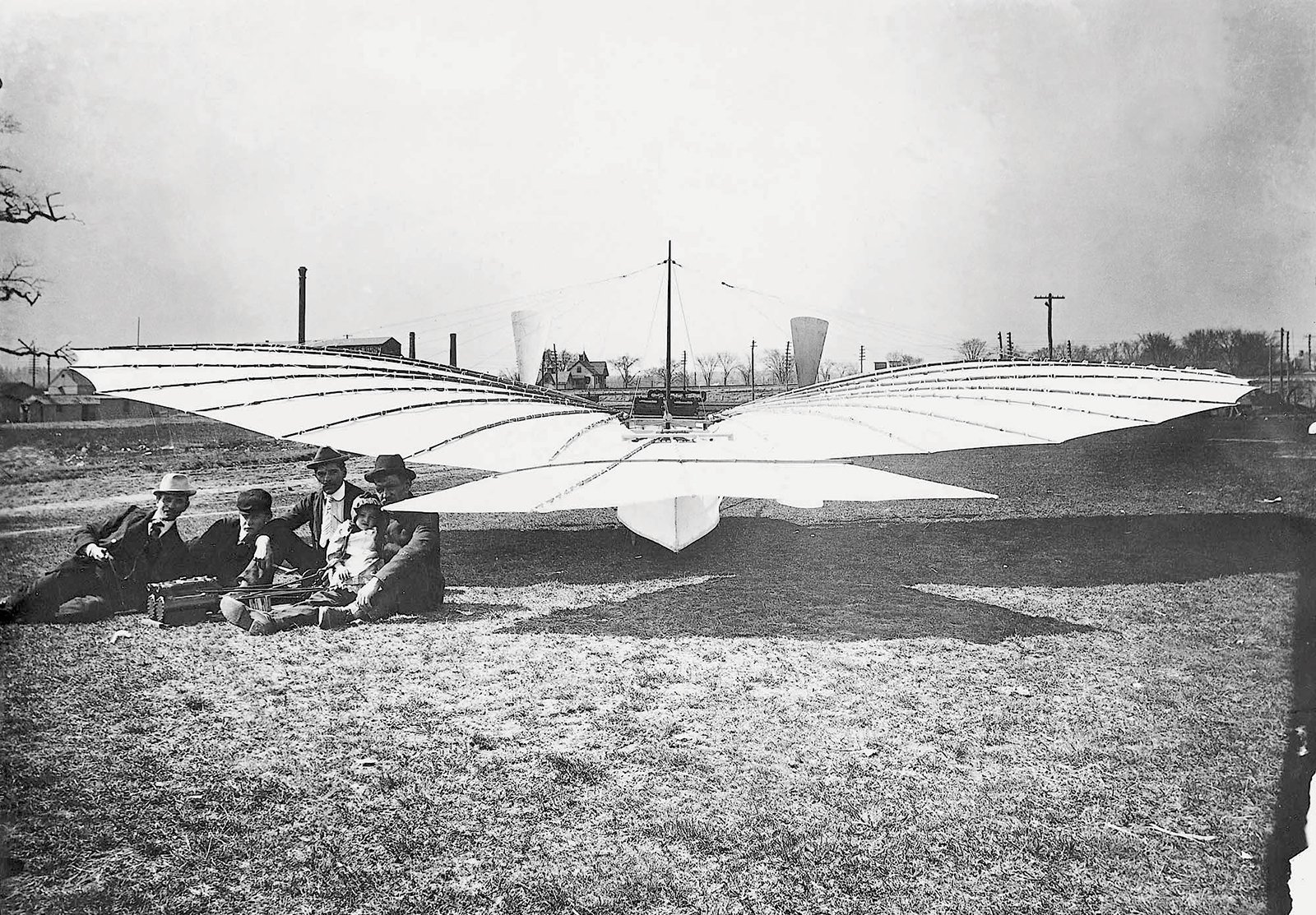

Gustave Whitehead’s Flying Machines

Gustave Whitehead was a German-born aviation pioneer that emigrated to the United States in 1893. He subsequently built and tested a number of flying machines, and some believe he achieved the first ever powered, controlled flight. As with most claims of this nature, it’s a difficult thing to prove and will most likely always have controversy surrounding it. Because of this, his machines and the alleged flights they took have a sense of mystery about them. To add to this mystery, Whitehead experimented with many different types of machines, including both manned and unmanned machines and both gliders and self-powered machines.

The New York American Journal Headquarters

Throughout my research into tall buildings and verticality, I’ve come across myriad examples of proposed and unbuilt structures. Some are alternate proposals by famous architects. Some are one-hit wonders that make their way into the mainstream history of skyscrapers. Some, like the one pictured above, are just intriguing and obscure images without much context. Details on this building are scarce, but from what I can find this is a proposal by Barney & Chapman Architects for the headquarters of the New York American Journal. It was located at Columbus Circle in New York City, on the site occupied by the Museum of Arts and Design today.

The Flying Machine by Ray Bradbury

With great power comes great responsibility. This is the major theme of Ray Bradbury’s short story from 1953, titled The Flying Machine. It was adapted into a comic in 1954 by Al Feldstein, and the full piece is pictured here. It tells the story of a meeting between an emperor and an inventor who has built a flying machine. The inventor is an optimist who experiences the full delights of flying, while the emperor is a pessimist who fears the technology will fall into the wrong hands. It’s a theme that runs much deeper than human flight, but Bradbury’s choice to feature the flying machine demonstrates the power of flight for humanity.

The Proctor Steel Tower

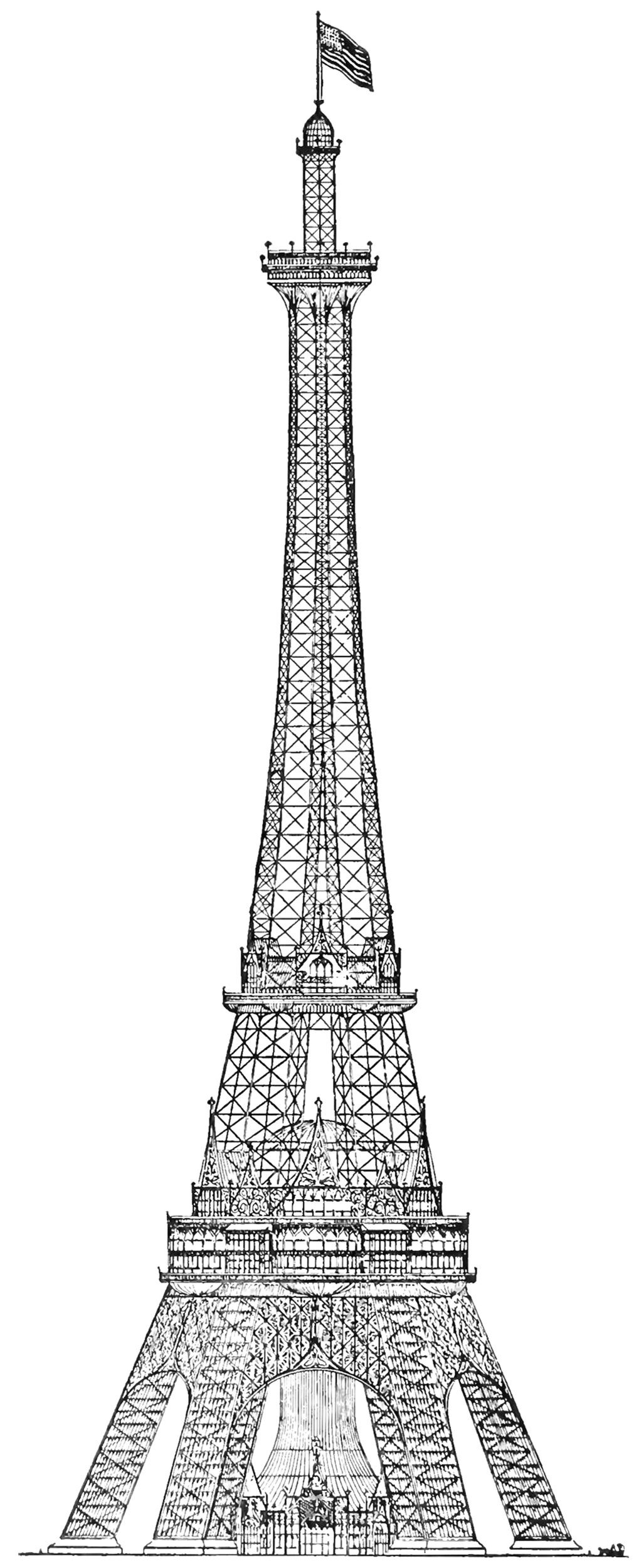

When the Eiffel Tower was completed for the 1889 World’s Fair in Paris, the world took notice. France had constructed the world’s tallest structure, and it immediately became the envy of the world. The next World’s Fair would take place in Chicago in 1893, and the organizers wanted to take the opportunity to out-do the Eiffel Tower with their own structure. The most successful proposal was the Proctor Tower, which is pictured above. It was 335 meters (1,100 feet) tall, which is roughly 12 meters (40 feet) taller than the Eiffel Tower.

Minnikin’s Flying Ship

‘Now go over fresh water and salt water, over hill and dale, and do not stop until thou comest to where the King’s daughter is,’ said Minnikin to the ship, and off it went in a moment over land and water till the wind whistled and moaned all round about it.

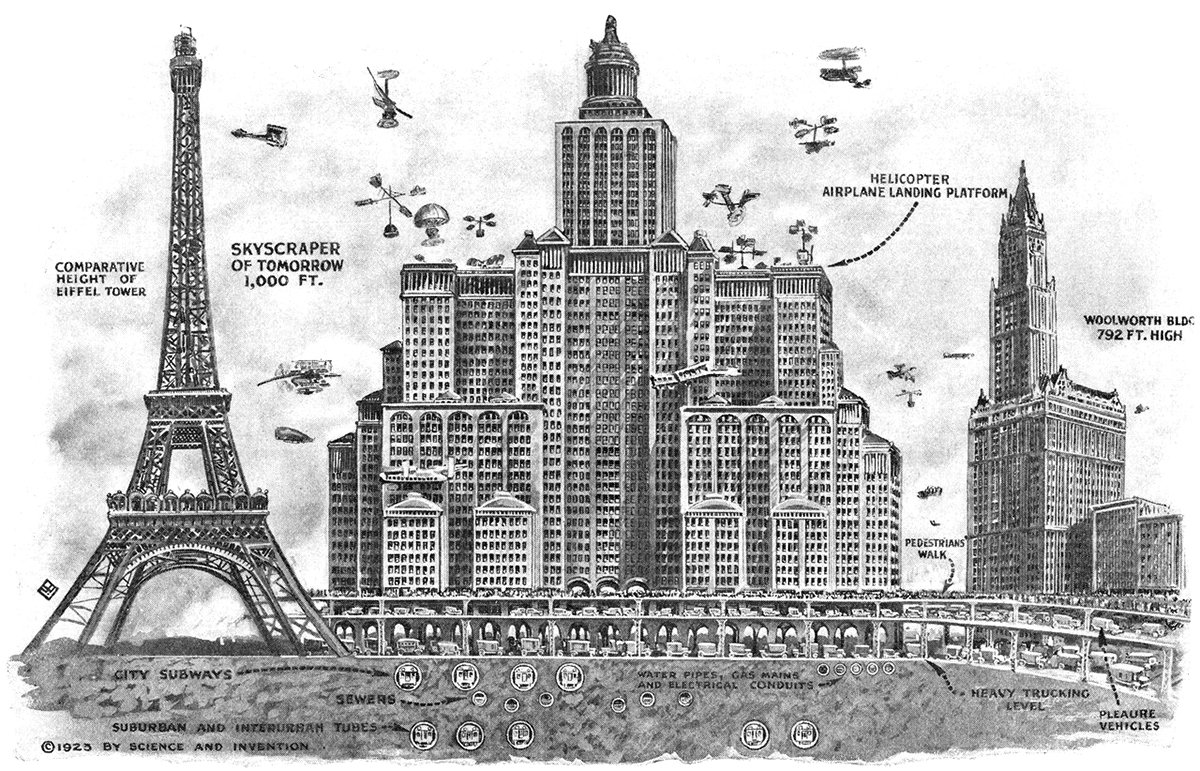

Skyscrapers of To-morrow

Pictured above is a 1923 illustration showing Harvey Wiley Corbett’s idea for a future skyscraper. Corbett believed buildings would continue to get taller and wider, resulting in massive, slab-like structures with aircraft landing platforms on their roofs and multiple underground levels of traffic. He compares his concept with two iconic buildings of the time, the Eiffel Tower and the Woolworth Building. These were both the tallest in the world when completed, which really hits home the sheer scale of Corbett’s structure.

Friedrich Gösling’s Proposal for the Reichstag

Pictured above is a competition entry for the original Reichstag building in Berlin. It was designed in 1871 by German architect Friedrich Gösling, and it’s a big departure from the Neoclassic design that ended up getting built. Gösling intended the design to embody the German way of life and the German idea of the state. He expressed these ideas with an organic plan and a Neogothic structure that seems to point upward with its myriad steeples and pinnacles. I suspect this upward focus was how Gösling’s idea of the German way of life in built form, because it’s so prevalent throughout his design. He was using verticality to project a sense of optimism about Germany and its future.

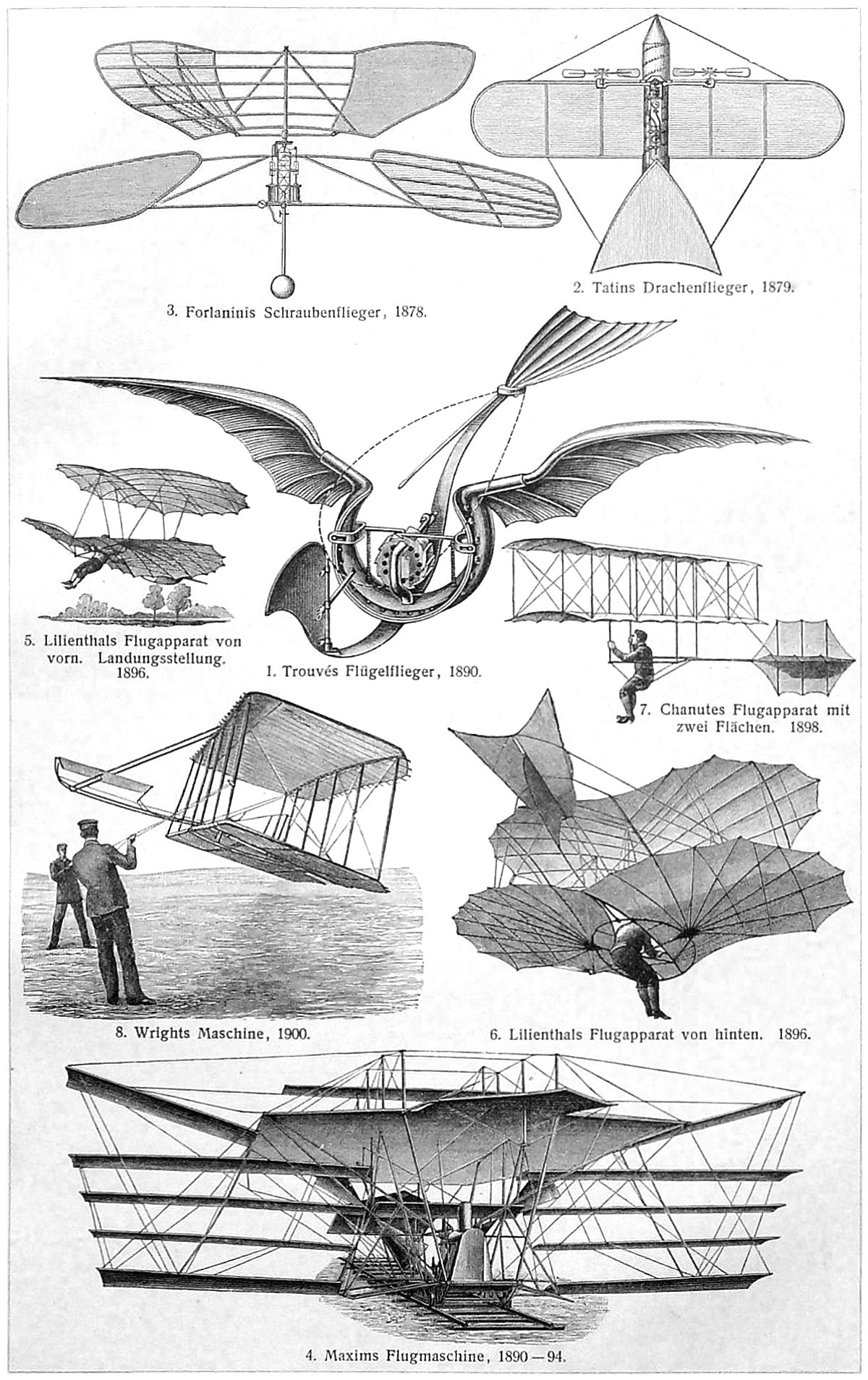

Early Aeronautics

Pictured above is a collage of early flying machines, originally published in the German encyclopedia Meyers Konversations Lexikon. I love collages like this because the illustrator inevitably must pick and choose which examples to show. This is most likely done for a combination of reasons, including available illustrations, the most famous examples, and page layout.

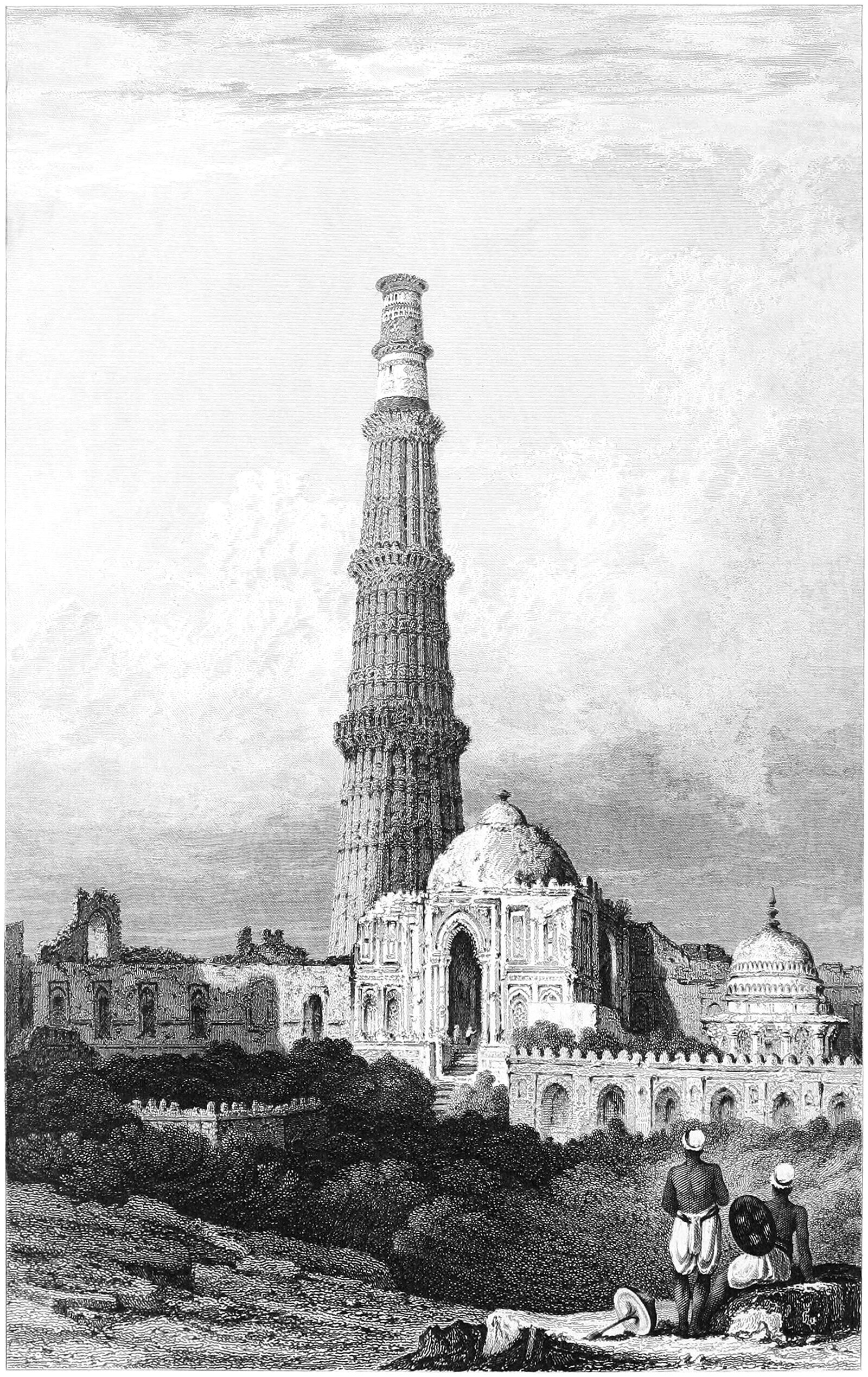

The Qtub Minar and the Verticality of Minarets

Pictured above is the Qtub Minar, which was built around 1200 just outside Delhi, India. It’s a fascinating example of a cross-culture artifact, and it departs from traditional minarets in three ways. First, it was built as the focal point of the Qutb complex and exists on its own, without an adjacent mosque. Second, it was built as a victory tower as well as a minaret. This means it was partly a monument to military victories, much like a triumphal column in Ancient Rome. Lastly, the minaret was designed by Muslim architects, but built by Hindu craftsman and laborers.

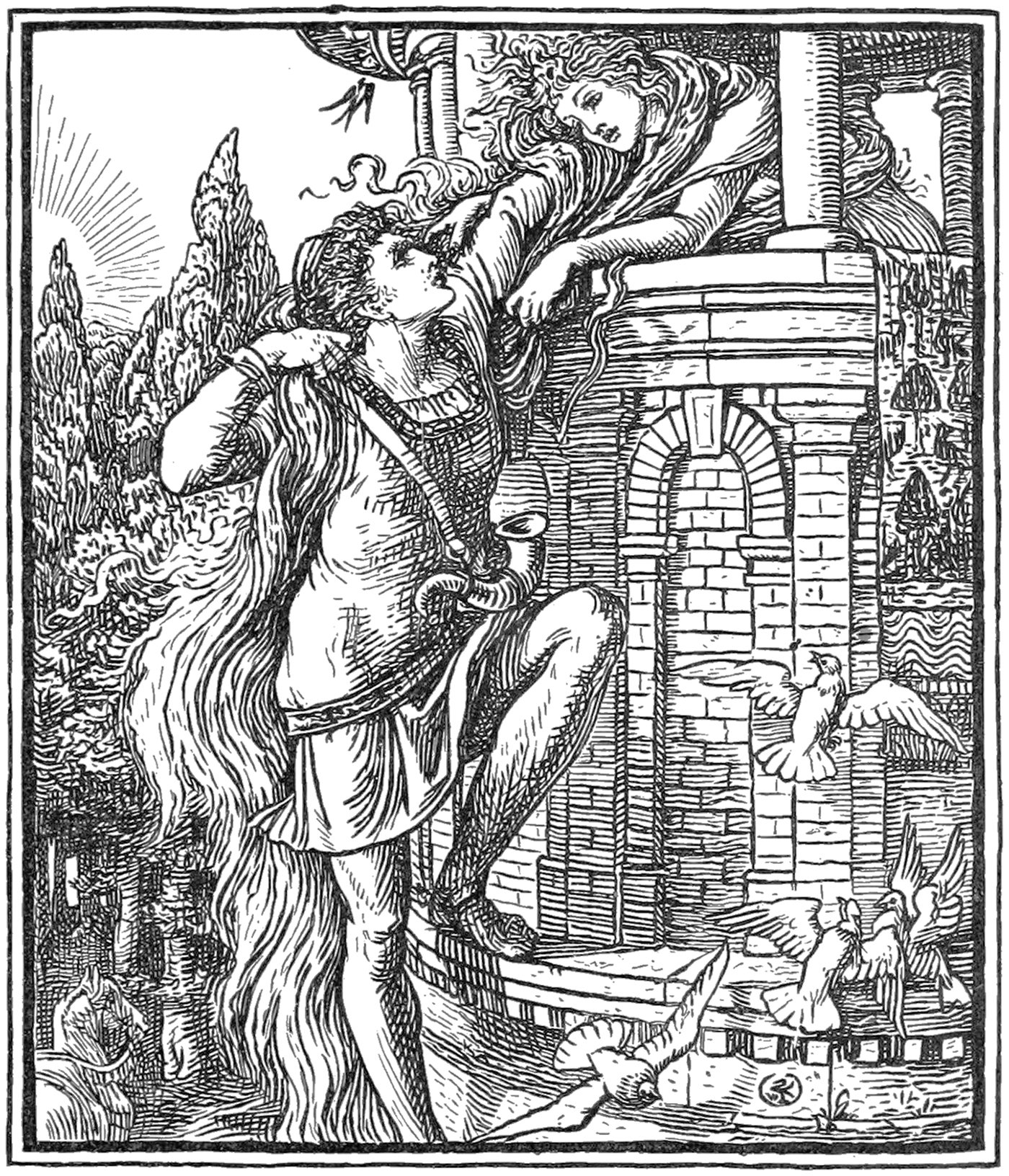

Rapunzel and the Isolation of Height

The story of Rapunzel and her long hair is a well-known folk tale with ancient origins. It’s the story of a damsel-in-distress and a prince who comes to rescue her. It’s well-worn territory in the world of folk tales, but the specifics of the story reveal a subtext that’s based on verticality.

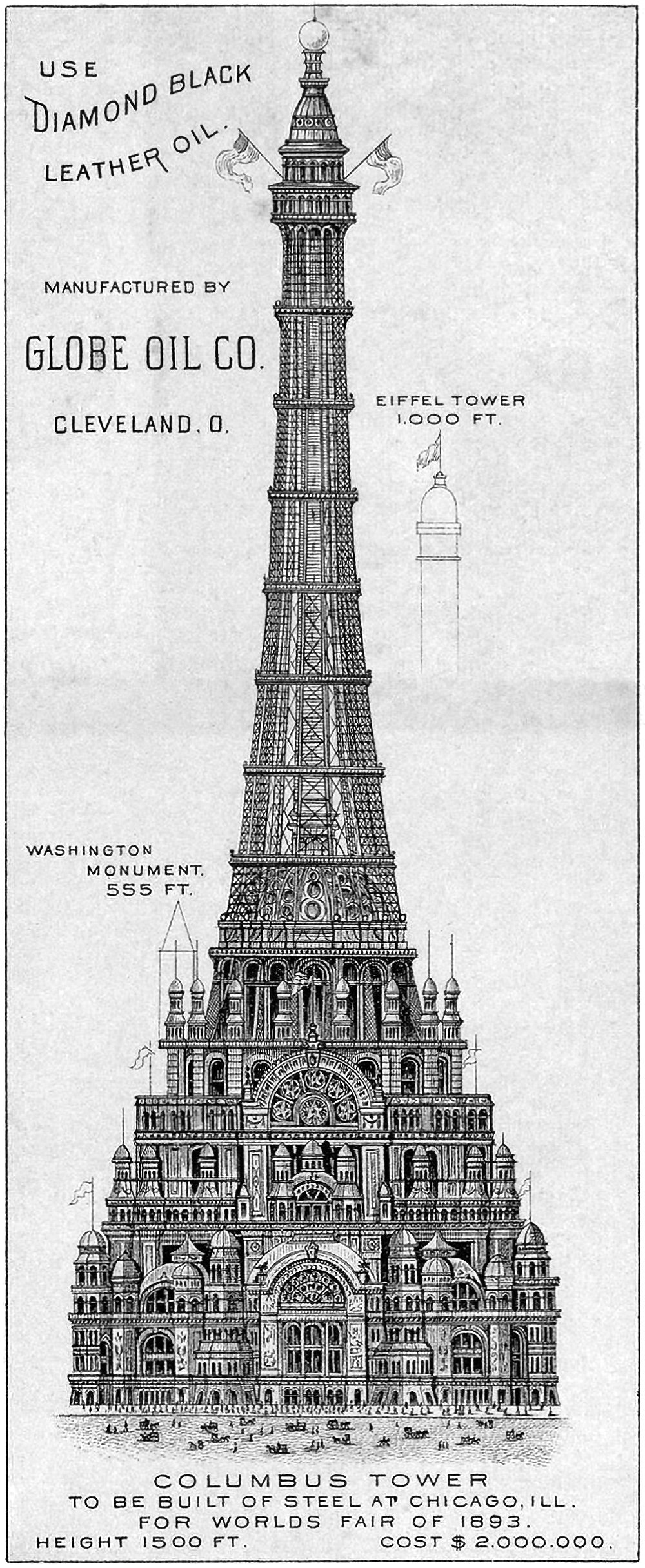

The Chicago Columbus Tower

Pictured above is the proposed Chicago Columbus Tower, which was designed to be the centerpiece of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. It was 455 meters (1,500 feet) tall and would’ve cost two million dollars at the time (roughly 62 million dollars today). It’s an elaborate and ambitious proposal that was meant to out-Eiffel the Eiffel Tower, which was built for the previous World’s Fair in 1889. As if to hit this point home, the above illustration includes height references to the Eiffel Tower and the Washington Monument, which would’ve been dwarfed by this new structure.

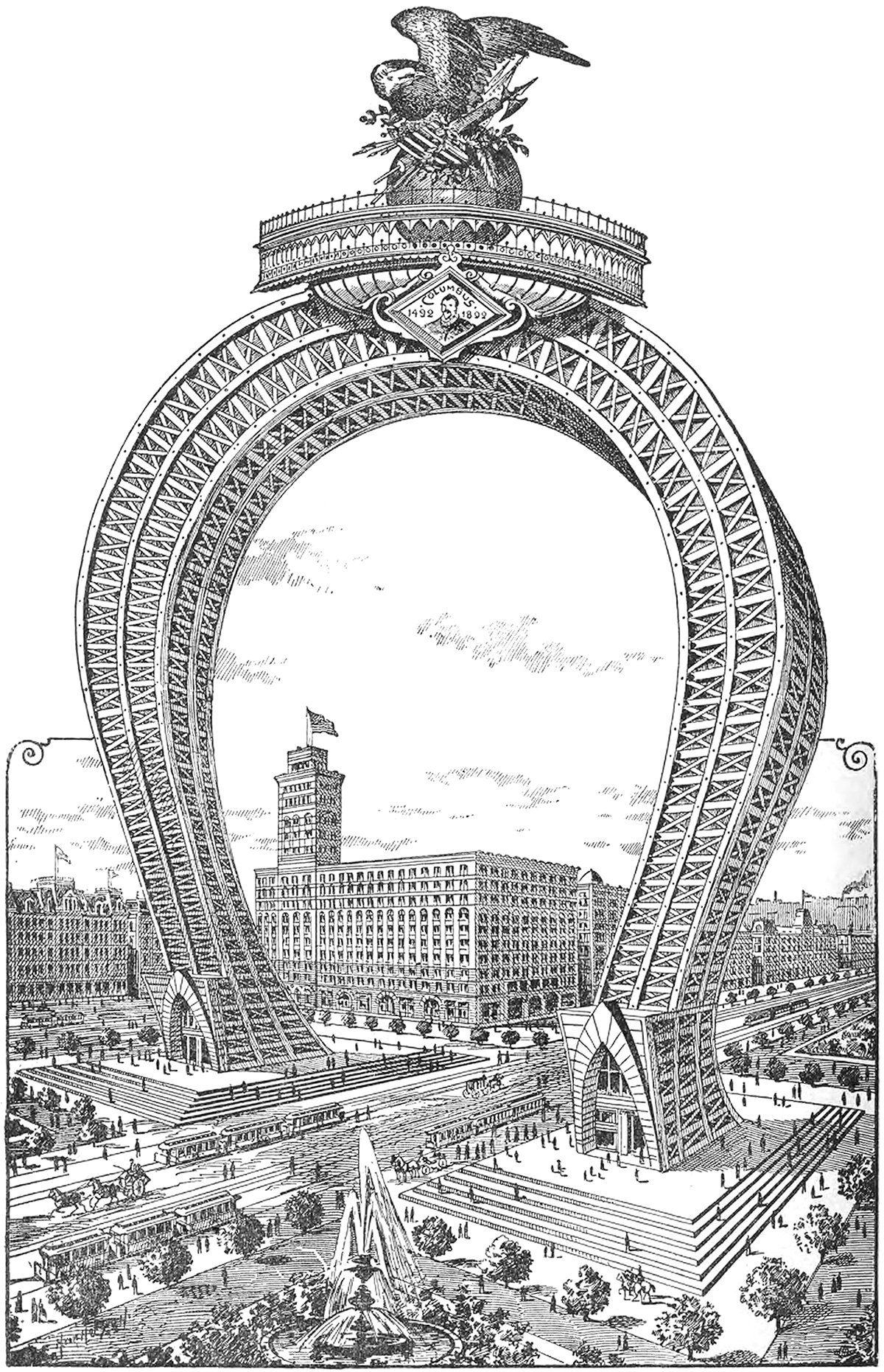

The Columbian Triumphal Arch

Here’s a doozy. It’s an 1891 proposal for a monumental arch that would’ve been the crown of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. It would’ve straddled South Michigan Avenue on the block adjacent to the Auditorium Building, which can be seen just behind the arch in the illustration. I can’t find any information on the designer, but whoever drew it up was no stranger to the Daniel Burnham quote make no small plans.

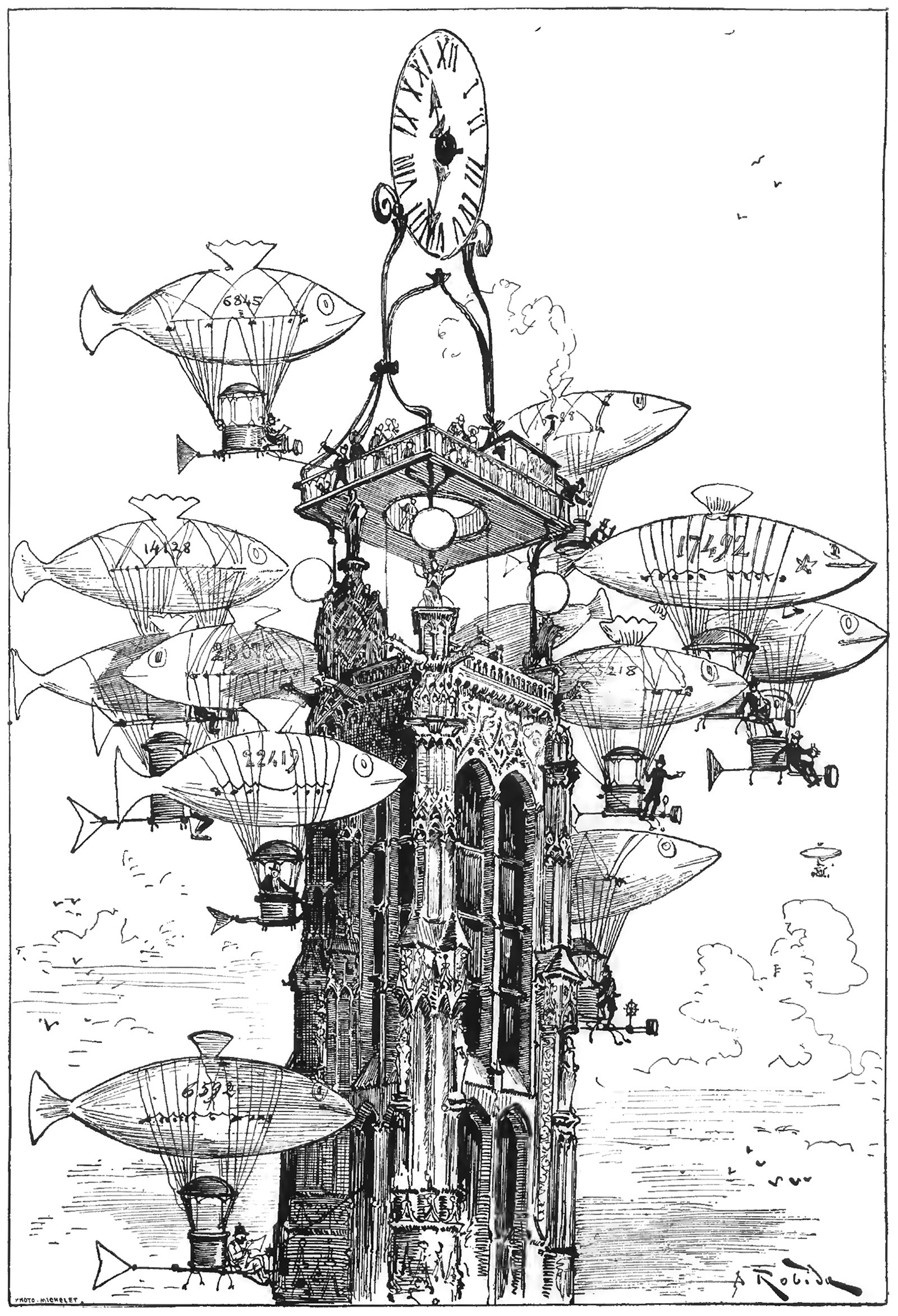

An Aerocab Station atop the Tour Saint-Jacques

The above illustration was drawn by Albert Robida for his 1883 novel Le Vingtième Siècle, or The Twentieth Century. This illustration was titled La Station d'Aerocabs de la Tour Saint-Jacques, or The Aerocab Station of the Tour Saint-Jacques, and it shows a raised platform and clock atop the iconic Parisian structure. Flocking around the tower is a group of dirigibles made to look like fish. What’s charming about the image is how the cluster of dirigibles resemble a school of fish, almost crowding out the tower itself from the image.

E.P. Frost’s Ornithopters

Pictured above is a photo of E.P. Frost’s second ornithopter prototype. It consisted of a large a pair of wings and a metal scaffold, and it was powered by an internal combustion engine. According to Frost, the machine successfully achieved liftoff under its own power in 1904. This wasn’t a sustained flight, however, but rather a jump or a hop.