Welcome to On Verticality. This blog explores the innate human need to escape the surface of the earth, and our struggles to do so throughout history. If you’re new here, a good place to start is the Theory of Verticality section or the Introduction to Verticality. If you want to receive updates on what’s new with the blog, you can use the Subscribe page to sign up. Thanks for visiting!

Click to filter posts by the three main subjects for the blog : Architecture, Flight and Mountains.

The Verticality of Clouds

I recently climbed Mount Saint Helens in Washington state, and the experience brought me face-to-face with the verticality of clouds. The photo above was taken just after dawn, and you can see two very different types of clouds in the sky. Just above my head was a dense, thin layer of altostratus clouds, which looked solid and dark from below. Far above this was a wispy pattern of cirrus clouds, which was much lighter in appearance. In addition to these, there were also groups of low-lying stratus clouds in the valleys below. What struck me in that moment was each of these cloud types was created by the exact same elements, the only difference was their height above the surface.

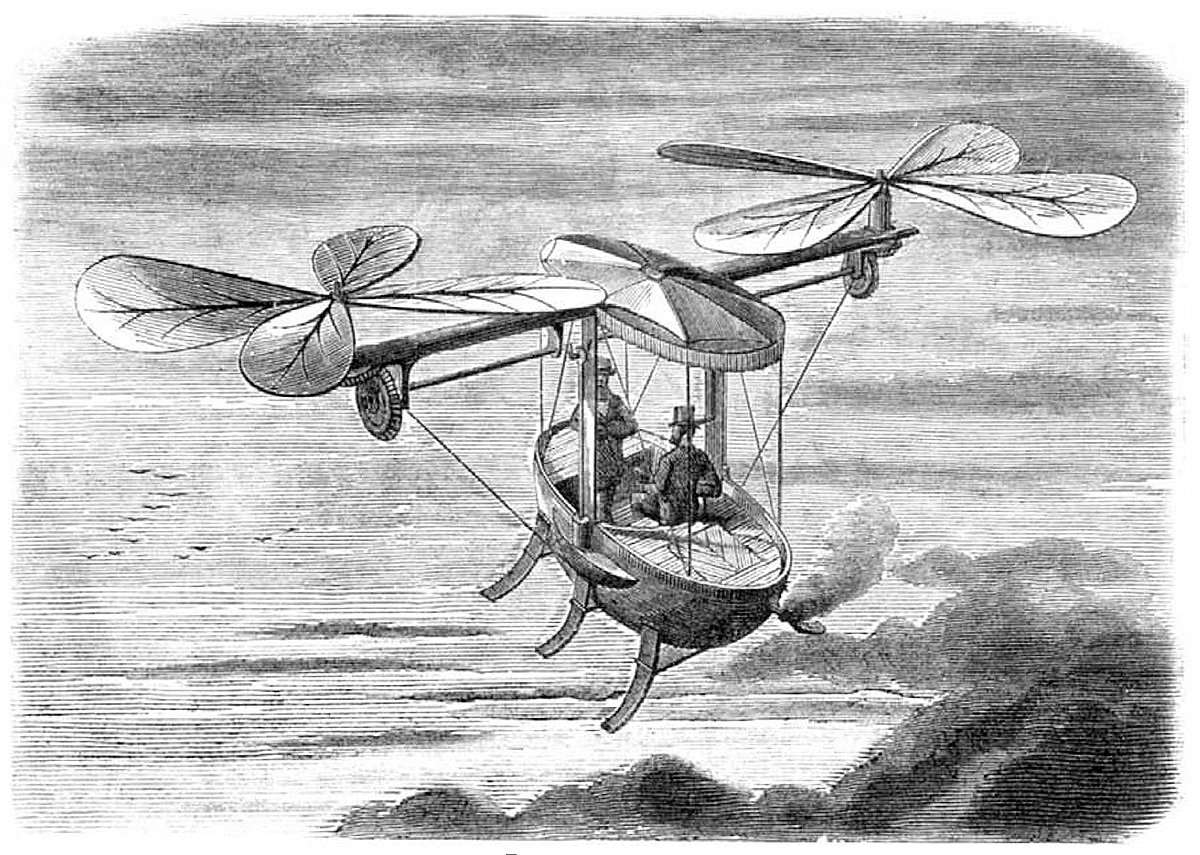

A Proposed Flying Machine

Pictured above is a proposed flying machine from an 1874 issue of Scientific American. The author is known only as W.D.G., and he wrote a detailed description of his machine to go along with the illustration shown here. Curiously, the description begins with this statement: Cannot we arouse a little more spirit and inquiry regarding the subject of a practical flying machine, and keep the ball rolling until the aim is accomplished?

“During my thirty-three hours on the Eiger I seemed to have been in a dreamland; not a dreamland of rich enjoyment, but a much more beautiful land where burning desires were translated into deeds.”

-Jürgen Wellenkamp, German mountaineer, 1930-1956.

The Myth of Pegasus and Bellerophon

Pictured above is a scene from ancient Greek mythology, showing the hero Bellerophon fighting the monstrous Chimera, with help from his winged-horse Pegasus. It serves as a dramatic climax in the story of the hero and his winged companion, and it’s one of many examples showing the power of verticality within ancient Greek mythology.

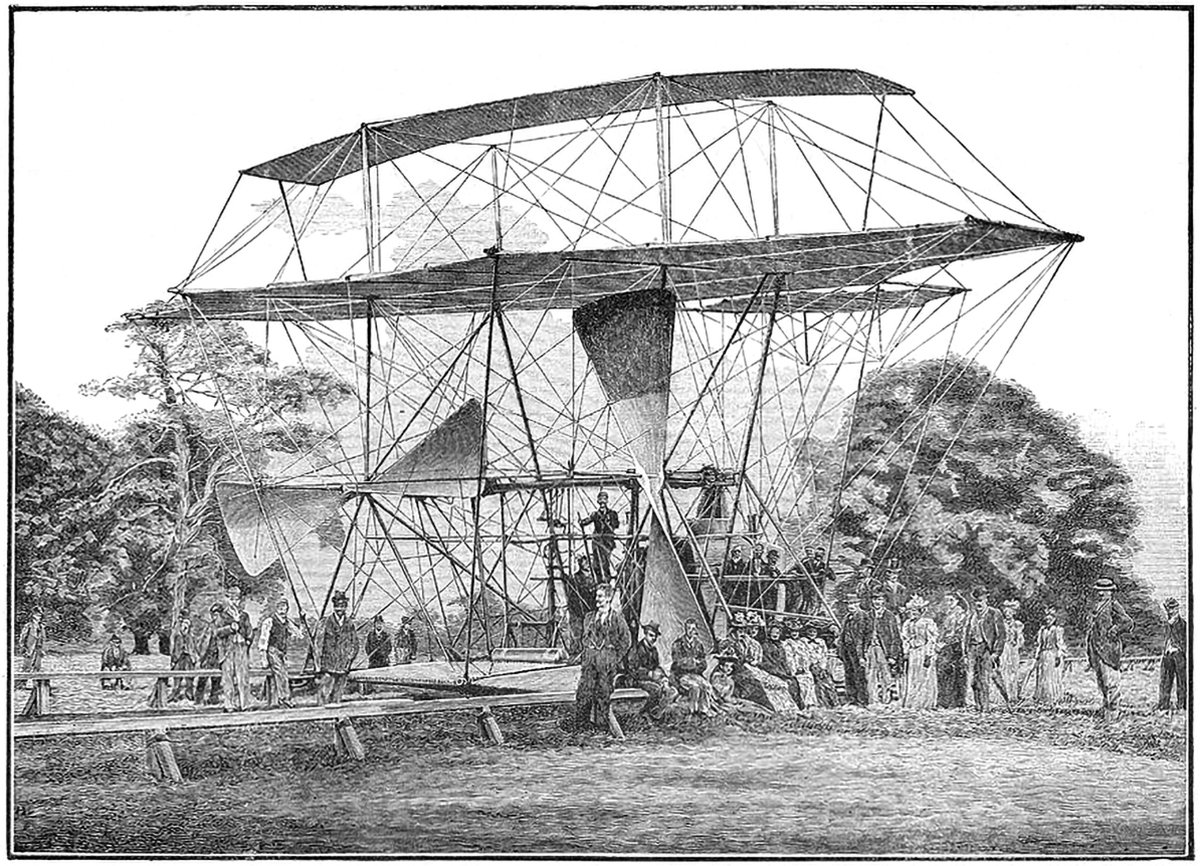

Hiram Maxim’s Flying Machines

Hiram Maxim was a prolific inventor who is best known as the inventor of the first automatic machine gun, as well as a series of flying machines he built and tested between 1889 and 1894. Pictured above is one of his later designs. It consisted of a series of wings tied together with a web of struts and cables, powered by a pair of massive wooden propellers.

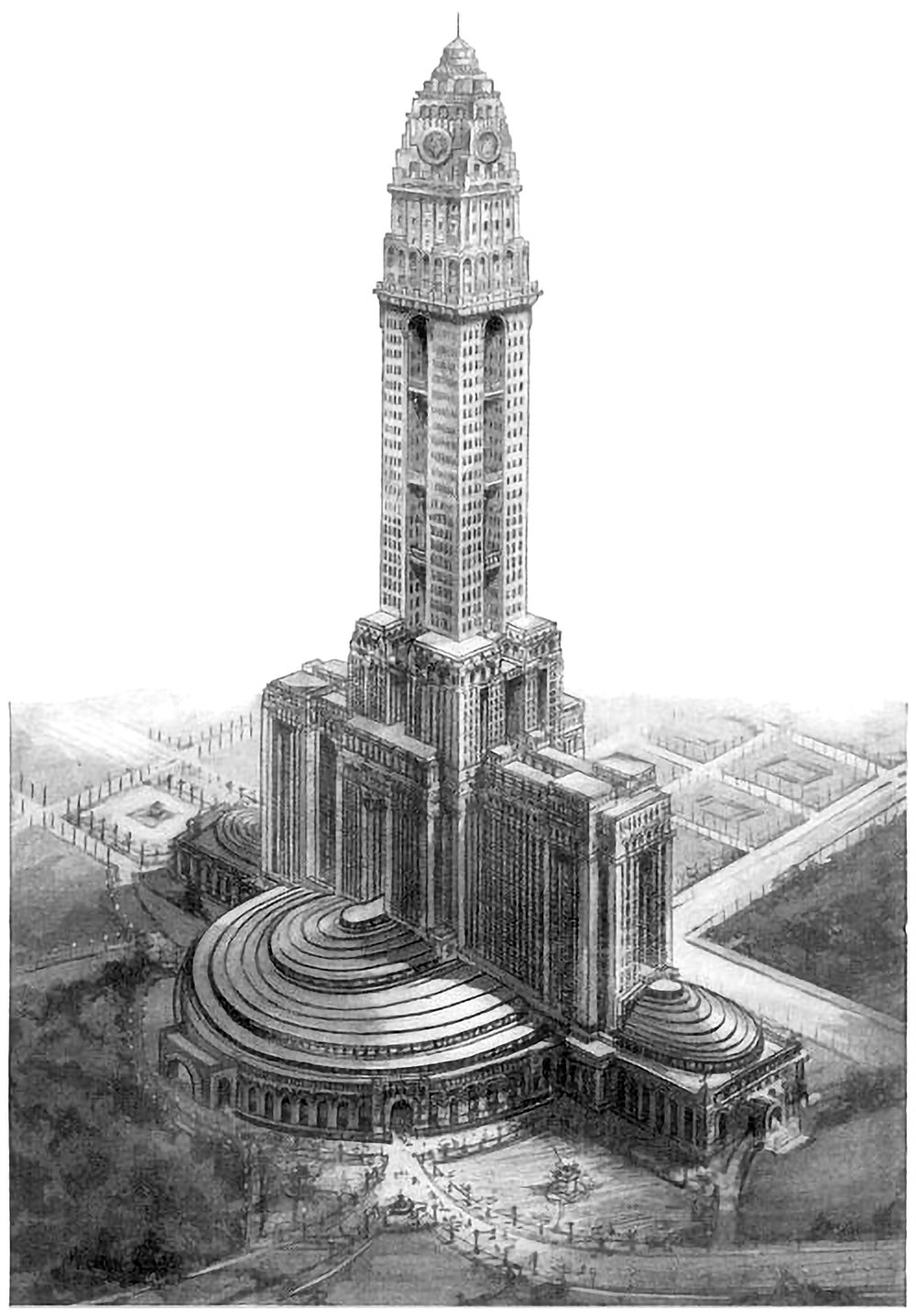

The Mole Littoria Project

Constructing the world’s tallest building is an act of politics just as much as an act of engineering. It’s a statement of accomplishment and power by all those involved. Paul Goldberger once wrote that you don’t build [the world’s tallest] skyscraper to house people, or to give tourists a view, or even, necessarily, to make a profit. You do it to make sure the world knows who you are. Pictured above is one example of this. It’s a 1924 proposal for the world’s tallest building, to be built in Rome. It was designed by Mario Palanti, who was an Italian architect who made his name in South America, and he proposed his design to Benito Mussolini, who enthusiastically approved the project.

Alexander the Great’s Flying Machine

The oldest myths and legends about human flight usually involve birds and other winged creatures that were already known to fly. These creatures were ready-made-packages of sorts. Harnessing their ability to fly by means of control provided the easiest and quickest path to human flight. Pictured above is one such example of this. It’s a mythical flying machine built by Alexander the Great.

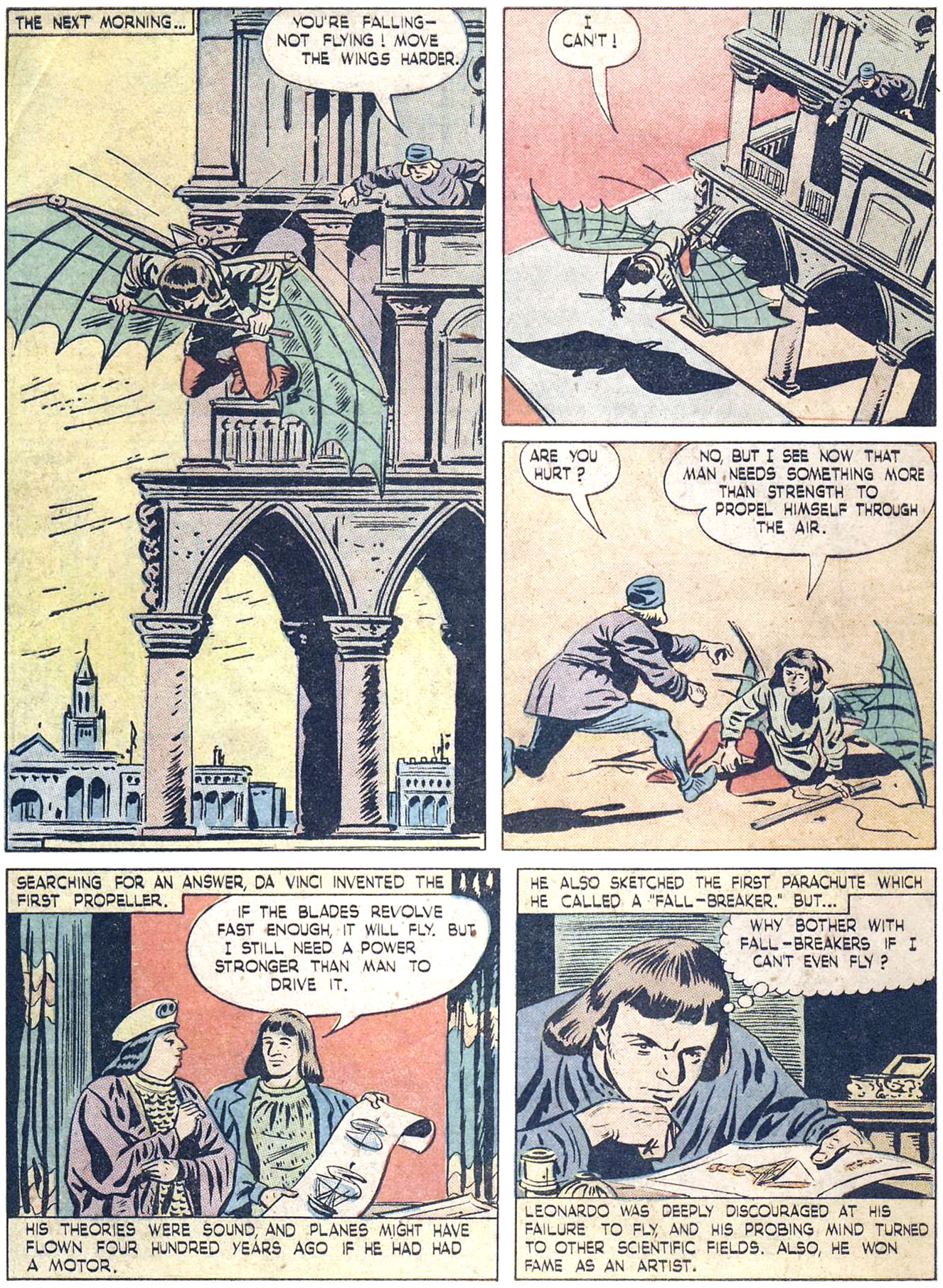

Leonardo da Vinci : 500 Years Too Soon

I see now that man needs something more than strength to propel himself through the air.

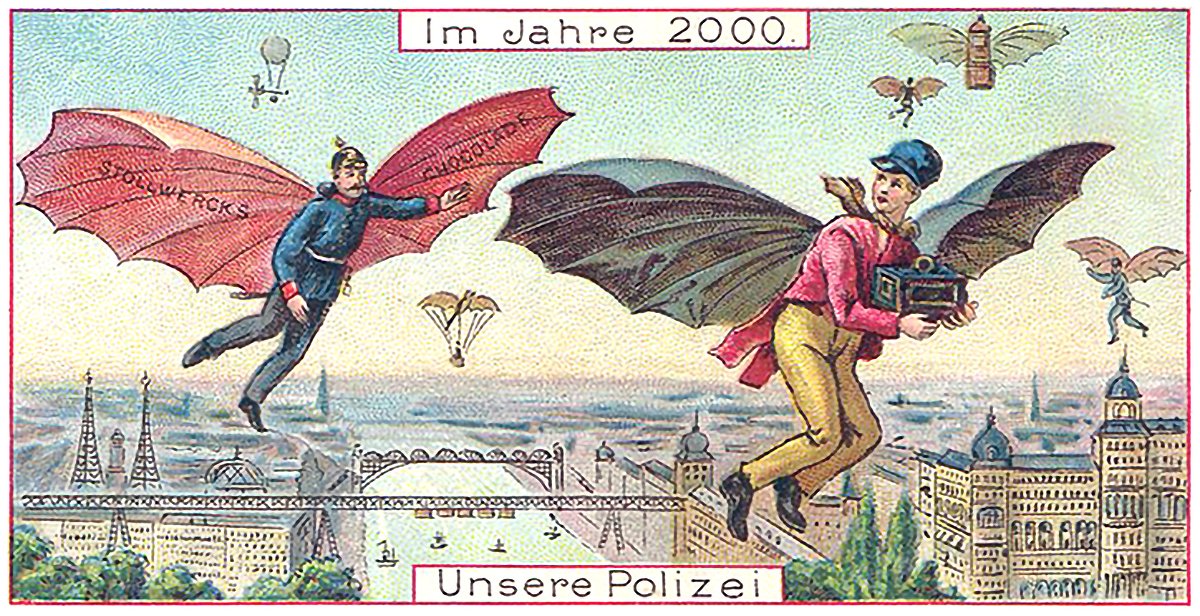

Im Jahre 2000 : In the Year 2000

The early twentieth century was a time of optimism towards the future. Aeronautics and flight were on the public’s consciousness, and there was much speculation about how the future would look once humanity conquered the skies. Pictured here is one such vision. It’s from a set of six cards titled Im Jahre 2000, which is German for In the Year 2000. What’s interesting about the set is that three of the cards deal with flight.

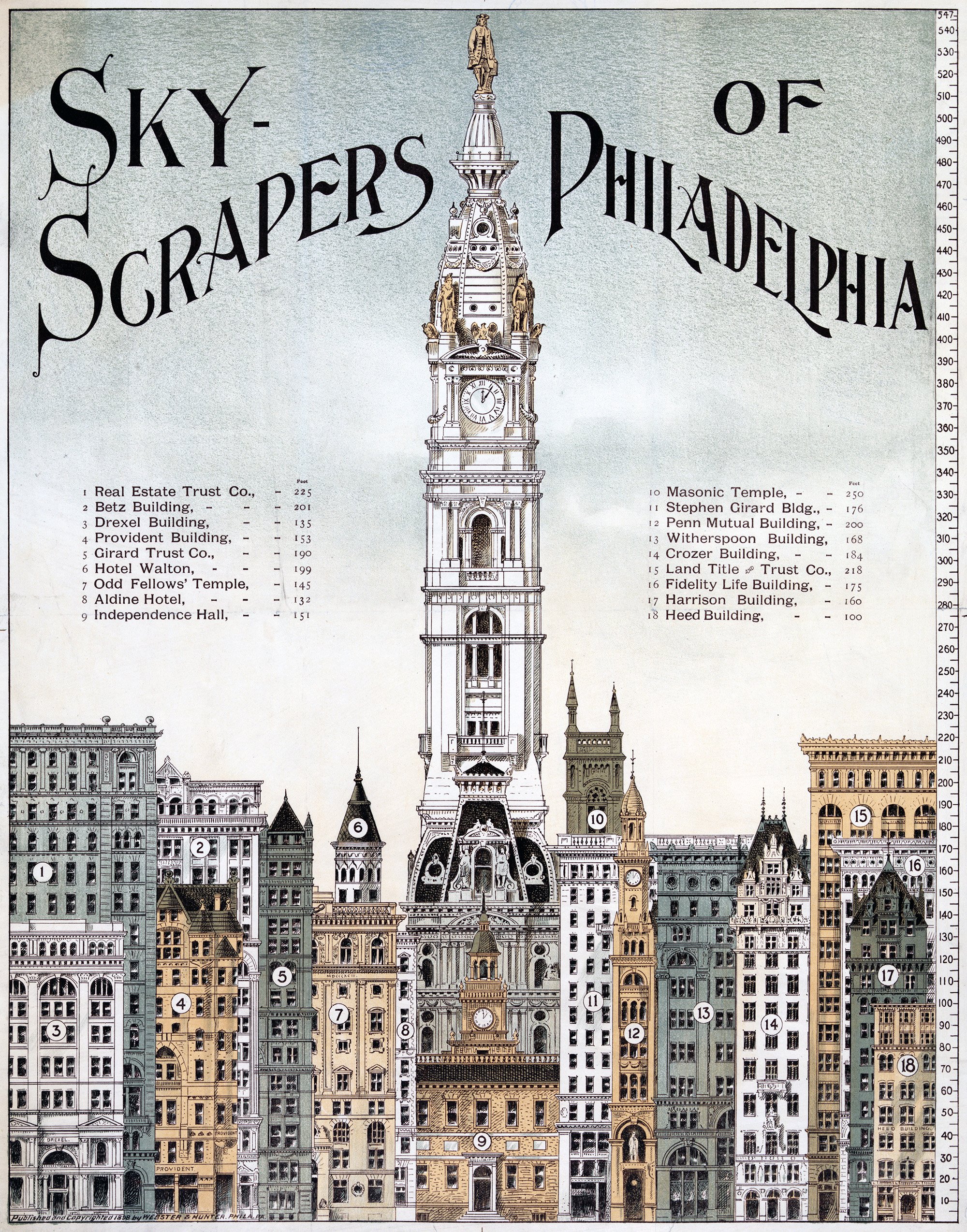

Skyscrapers of Philadelphia

The illustration above shows a lineup of tall buildings from 1898 in Philadelphia. All of them are of similar height, save for the City Hall Clock Tower. It stands alone, rising to a height of 548 feet, or 167 meters. It was the tallest building in the world when it was completed in 1894, and remained so until the completion of the Singer Building in New York in 1908. This status as the world’s tallest building is reinforced by the illustration, which shows it utterly dominating the other buildings in the city.

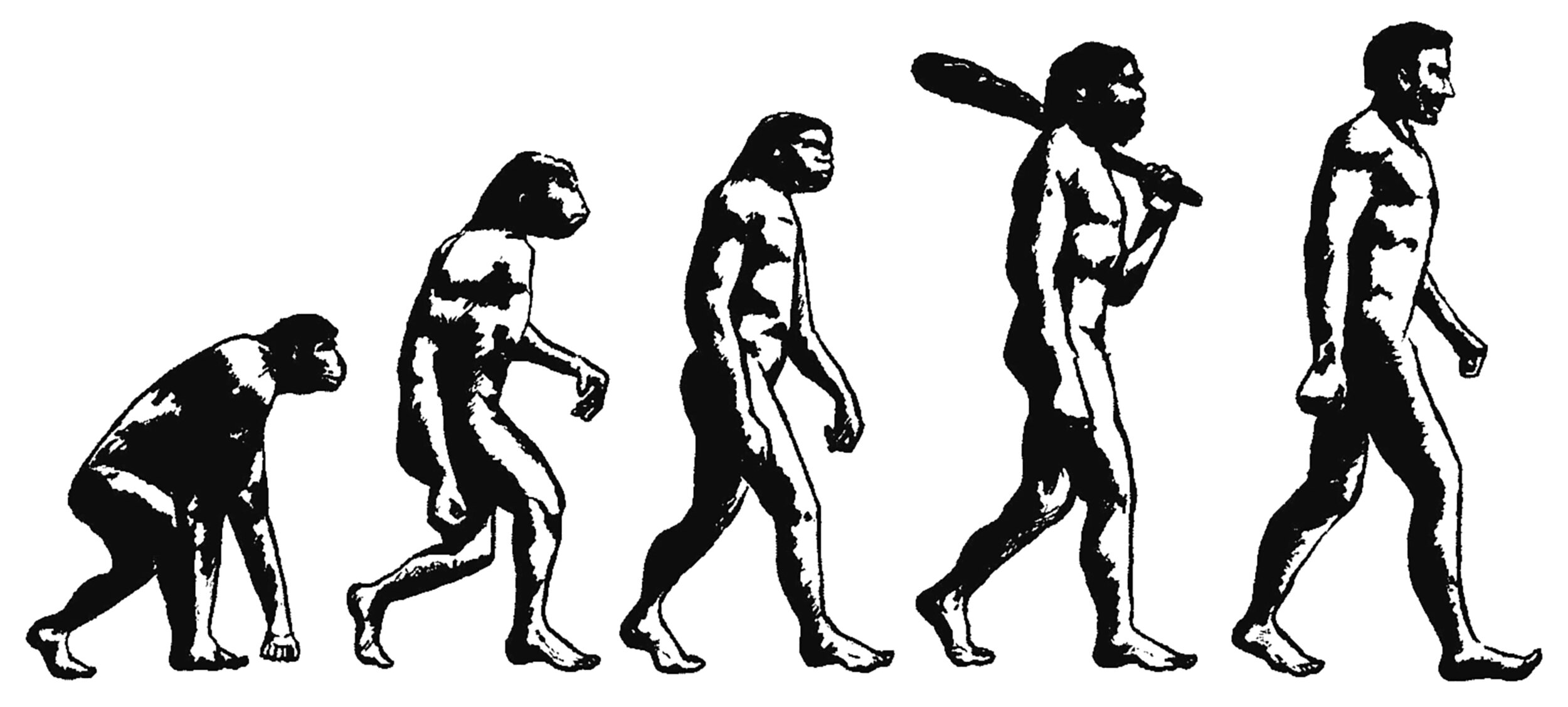

The March of Progress and the Fallacy of Progressive Evolution

Evolution and natural selection are tricky concepts to represent in an illustration. This is partly true because the reality of these processes is so complex and nuanced that some type of simplification is required when introducing them. This is a fine line however, because each concept can easily be over-simplified to the point of confusion. This is exactly what happened with the illustration above. At first glance, it appears to be a simple meme that shows how the human species went from moving on all fours to walking upright, but behind this is a fascinating and painfully unfortunate backstory about the nature of evolution.

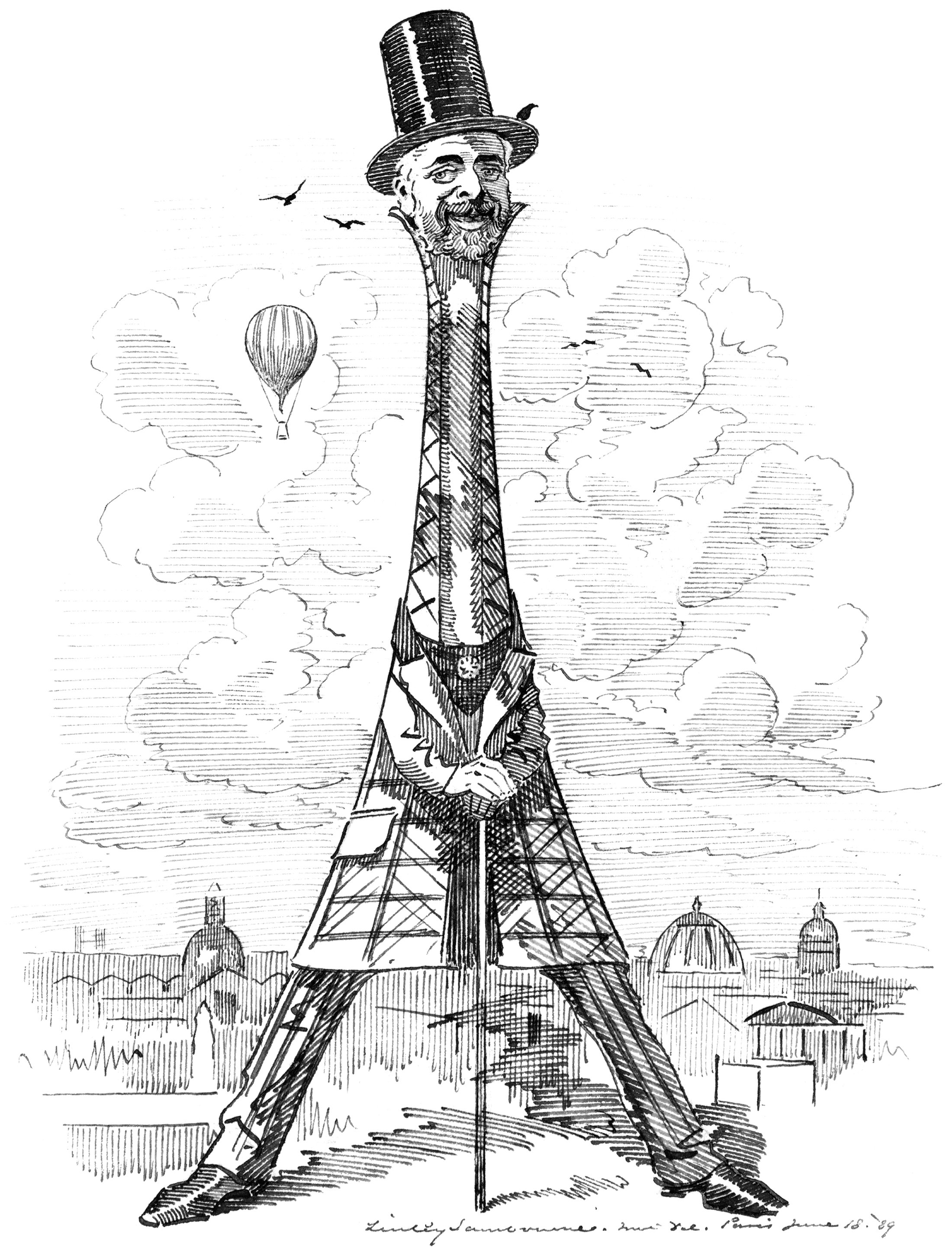

Eiffel as his Tower

Our buildings reflect our values and needs. This is especially true of our tall buildings, because they cost so much to build. When the Eiffel Tower was built in Paris, it reflected a worldwide drive for height in our buildings that was emerging at the time. It was a such a powerful statement of verticality that the man who designed it became something of a celebrity. He became linked with the tower in the eyes of the public, so much so that it was named after him like one of his children. This rarely happens with a building, but it demonstrates just how big an impact the Eiffel Tower had on the world.

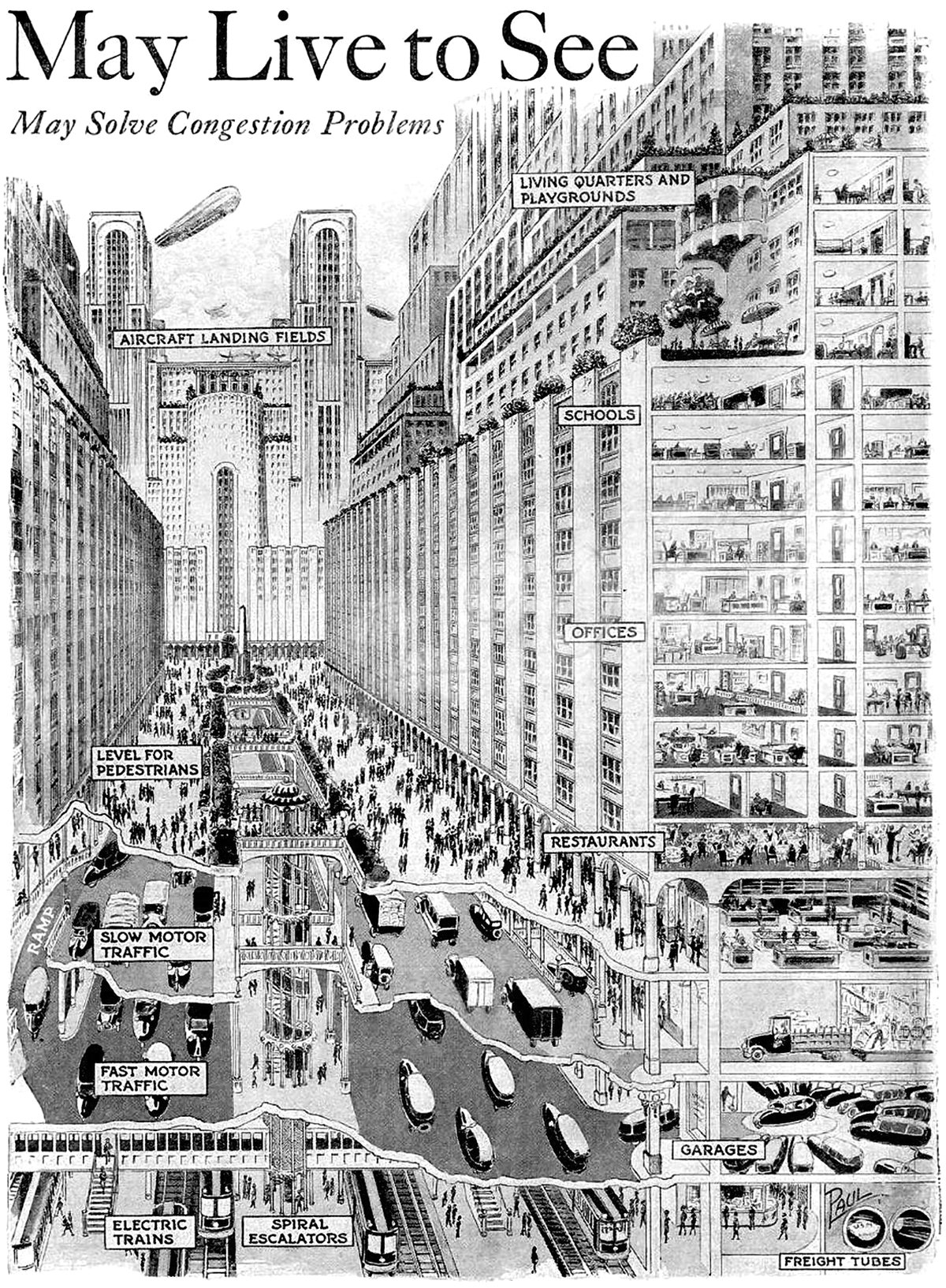

How You May Live and Travel in the City of 1950

Pictured above is a vision for a future city from 1925, which predicted what cities would look like in 1950. It’s quite an ambitious proposal, since it required sweeping urban changes to occur in only 25 years. The changes feature a vertical separation of city functions that start below the ground and end on top of skyscrapers.

“Mountaineering offers an emotional experience which cannot otherwise be reached.”

-George Mallory, English Mountaineer, 1886-1924.

The Flying Trunk

It was no ordinary trunk. Press on the lock and it would fly. And that’s just what it did. Whisk! It flew up the chimney, and over the clouds, and away through the skies. The bottom of it was so creaky that he feared he would fall through it, and what a fine somersault he would have made then!

The Verticality of Roller Coasters

One of the most visceral sensations a human can experience is a sudden fall. This quick, downward acceleration of the human body can evoke feelings of terror if it’s unplanned or unwanted, or feelings of thrill and delight when it’s expected. For many of us, the sudden pull of gravity conjures up all these feelings at once. Roller coasters tap into this concept, and they meticulously curate it in order to maximize these feelings for their riders. A ride on a roller coaster pushes and pulls your body in myriad different directions, allowing a rider to experience gravity-like forces in many different directions. It’s an experience rooted in verticality, which is what gives them such appeal.

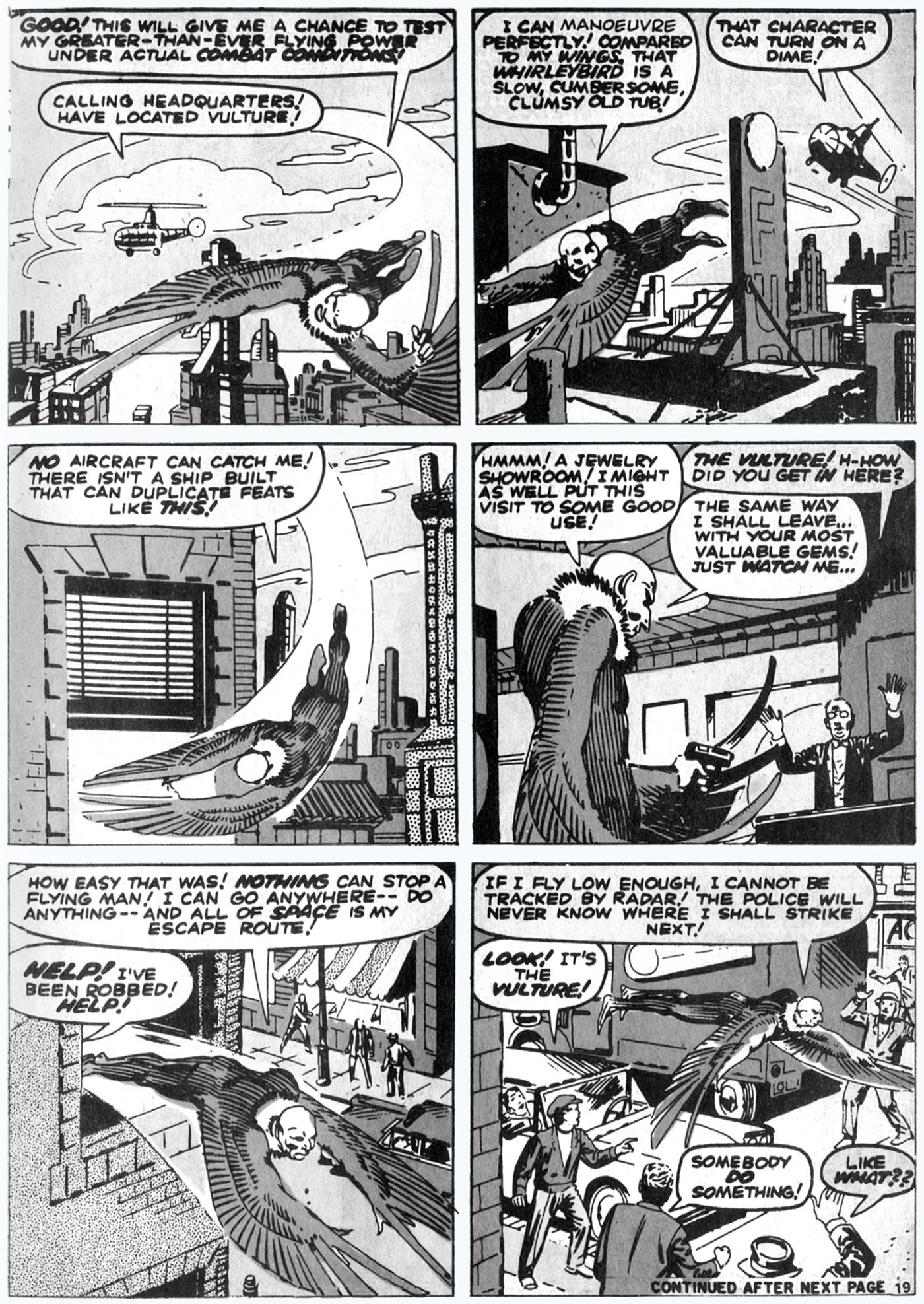

Nothing can stop a flying man!

In many ways, comic books function as folk tales for modern society. They tell stories of the eternal conflict of good and evil, with super-human characters who can do things common people can’t. Of these abilities, the most common is flight. The ability to fly is something every person understands, and it gives any character an immediate and excessive advantage over anyone who can’t. Pictured above is a page from a Spider-Man comic from 1973, showing the villain testing out his newly-acquired flying power.

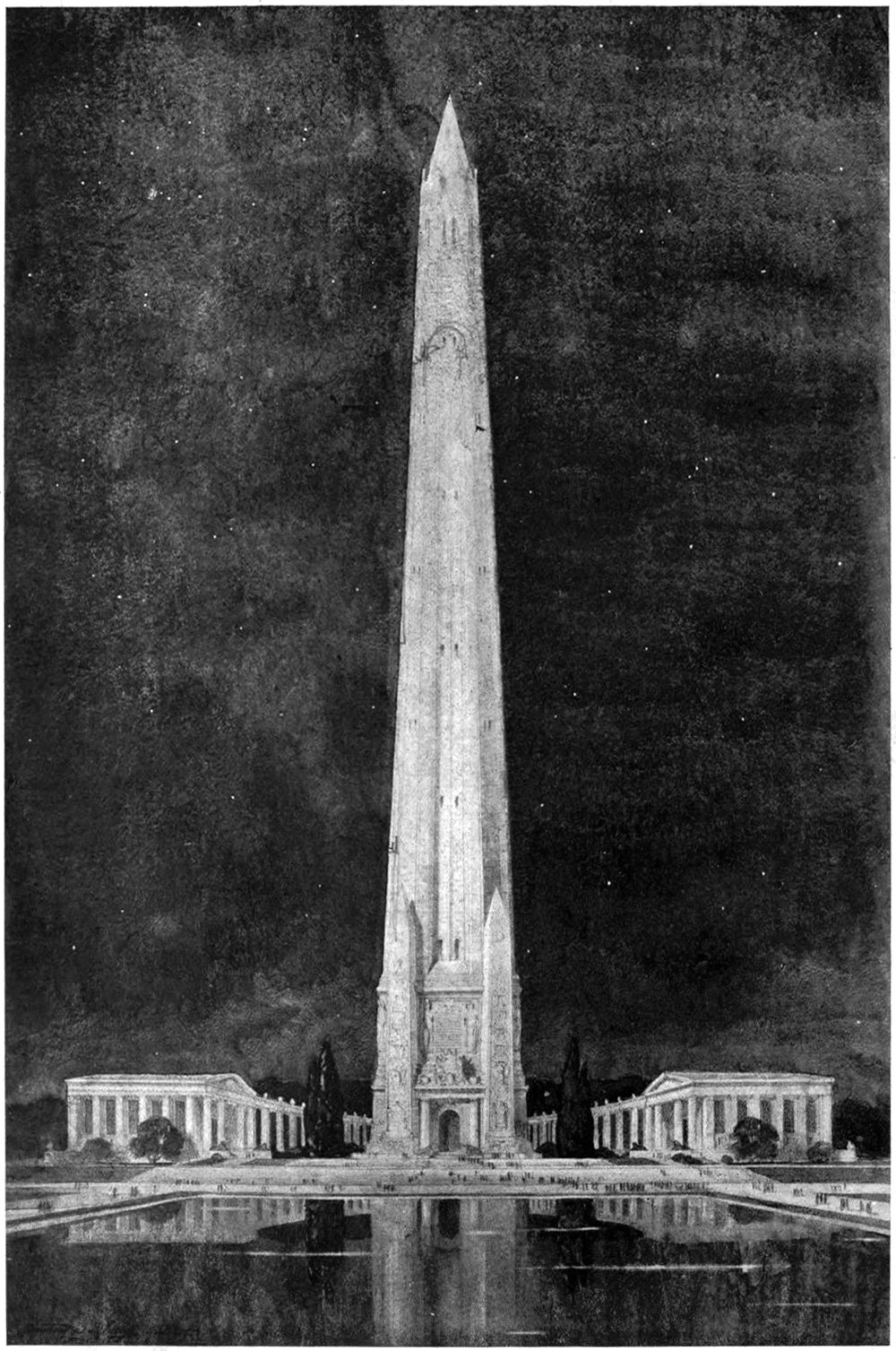

A Design for a National Memorial

Monuments and memorials are tricky beasts to design. Unlike a normal building, they’re imbued with meaning and symbolism that can be highly subjective. They’re not just buildings, but repositories for history and memory. This means they carry responsibilities to the person or event they are meant to symbolize. That’s what makes the above illustration so difficult to understand. It’s described only as Design for National Memorial. This is tough, because it doesn’t even make a claim to what it’s memorializing. One thing is clear, however; the designer was motivated by verticality.

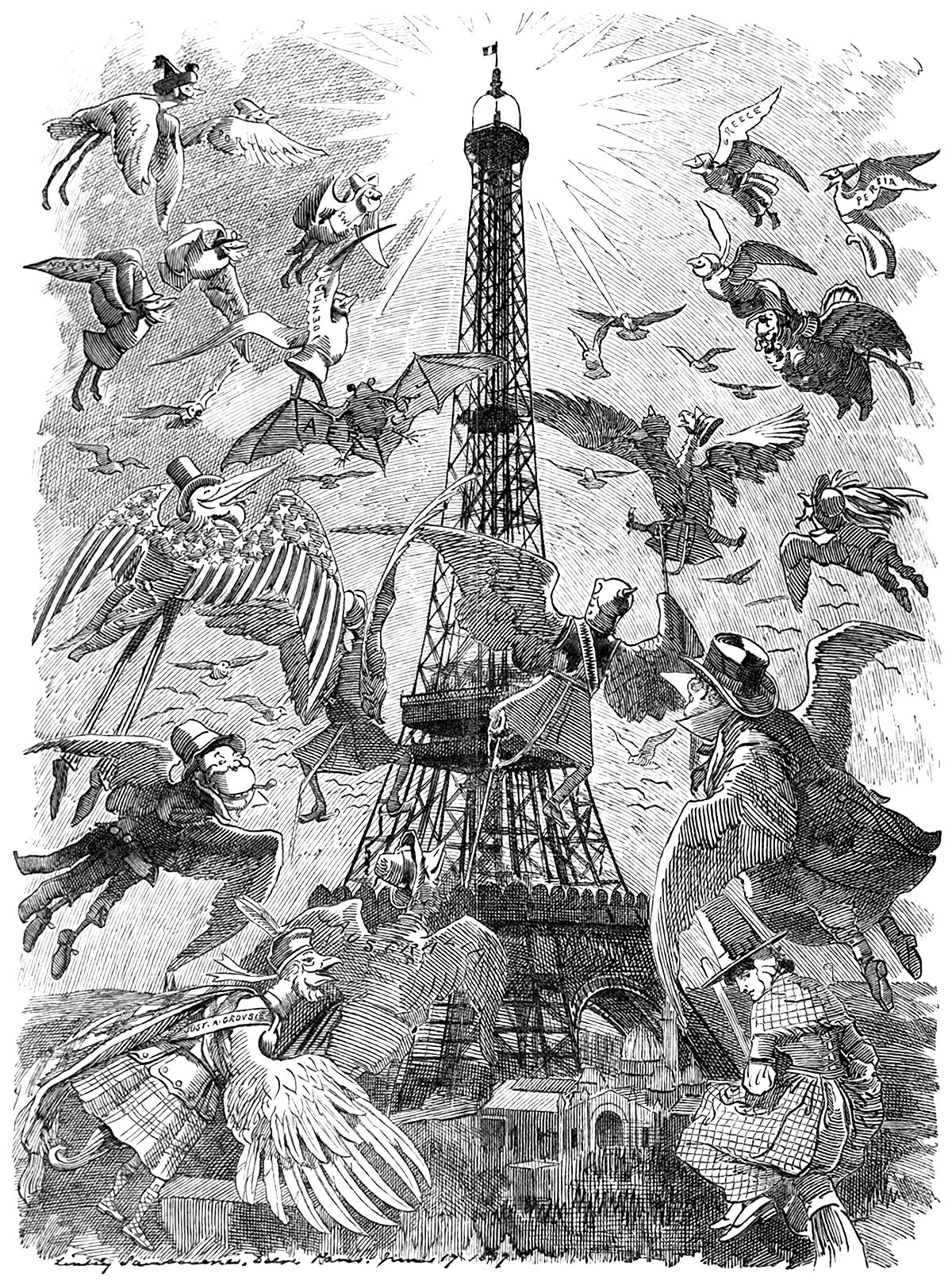

The Eiffel Tower Effect

When the Eiffel Tower was completed in 1889 for the World’s Fair in Paris, it changed the world. It re-defined what humans were capable of, and it gave the city of Paris an architectural icon that hasn’t faded with age. It was the tallest structure in the world, and it allowed its visitors to achieve verticality. As such, upon its completion the world took notice. Countless media sources reported on the structure, and it instantly took its place on the world stage. Pictured above is one such example of this. It’s an illustration from an 1889 issue of Punch magazine, and it shows a flock of birds flying toward the Eiffel Tower. These birds represent the countries of the world, and the piece was meant to symbolize the world’s envy for the iconic tower.

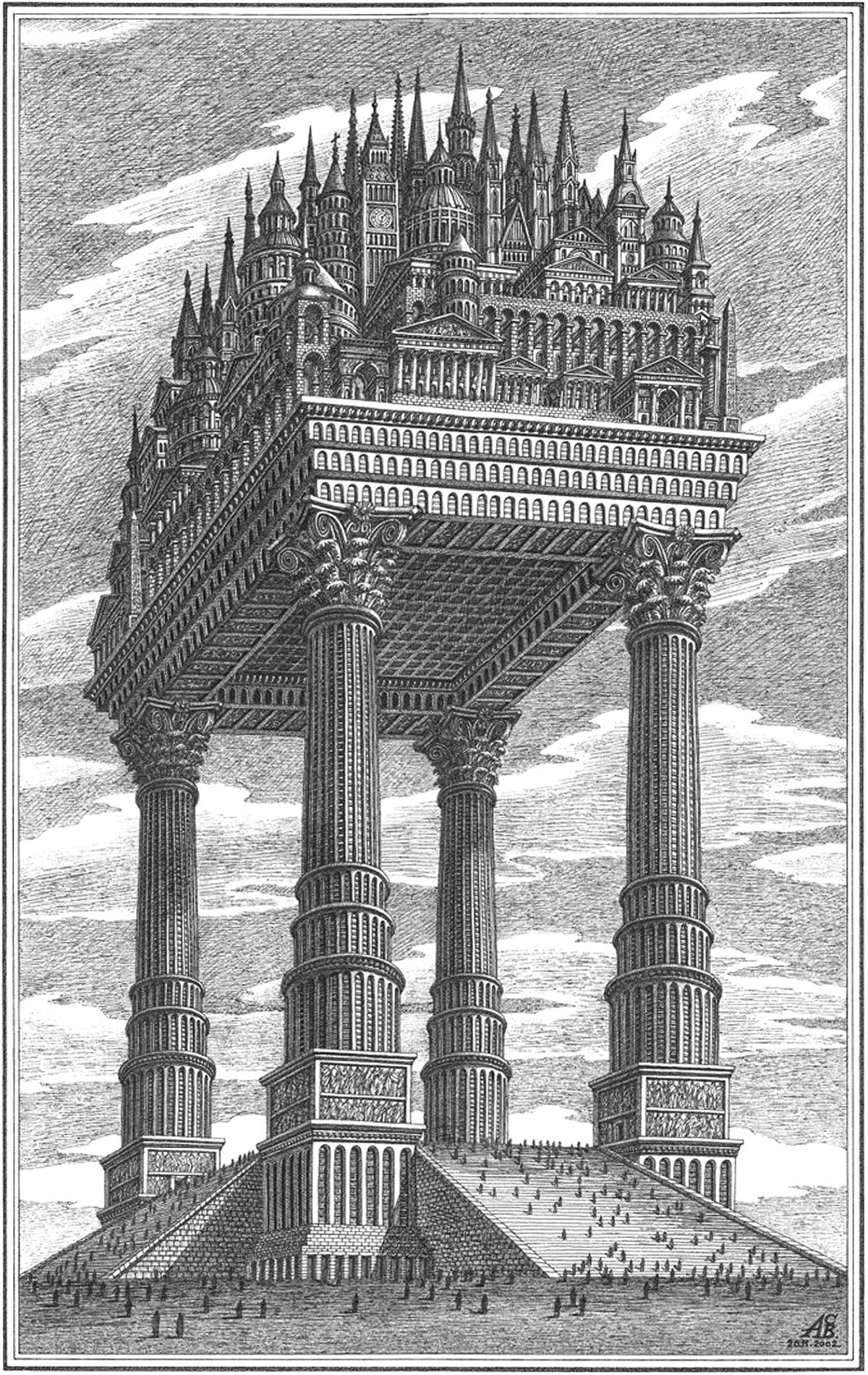

The Magic City

Pictured above is an illustration by Russian architectural theorist Arthur Skizhali-Weiss. It’s part of a series called The Magic City, which includes fictional realities dreamed up by the architect from 1999 to 2014. Apart from being an interesting composition of architectural forms, it embodies a few themes related to verticality.