Welcome to On Verticality. This blog explores the innate human need to escape the surface of the earth, and our struggles to do so throughout history. If you’re new here, a good place to start is the Theory of Verticality section or the Introduction to Verticality. If you want to receive updates on what’s new with the blog, you can use the Subscribe page to sign up. Thanks for visiting!

Click to filter posts by the three main subjects for the blog : Architecture, Flight and Mountains.

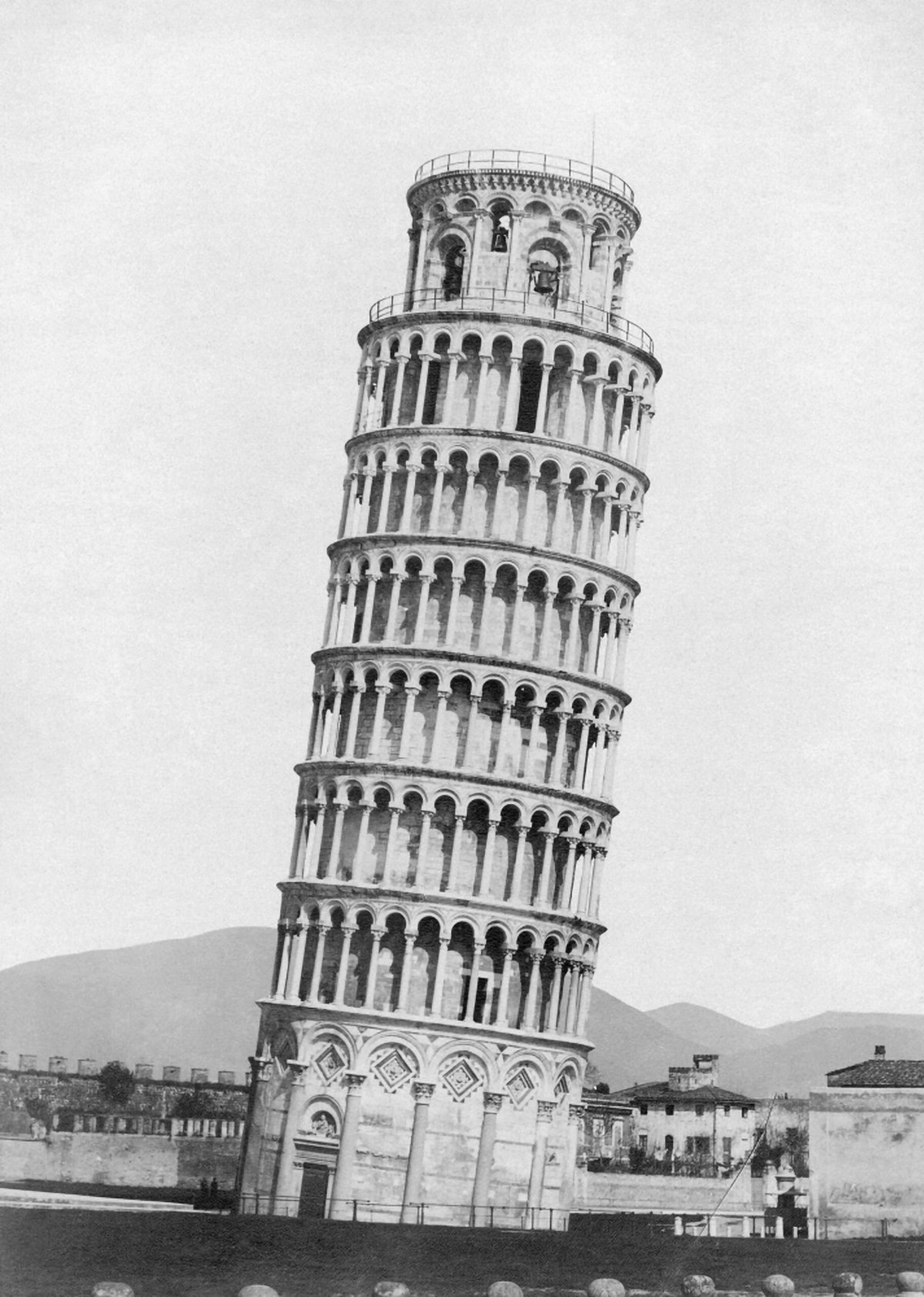

The Leaning Tower of Pisa and the Axis Mundi

Pictured here is the campanile at the Pisa Cathedral, known worldwide as the Leaning Tower of Pisa. The tower is world-famous for its iconic four-degree lean, and has become a major tourist attraction for the town of Pisa. This lean has allowed the campanile to become a symbol of the city. If you think of Pisa, you think of the Leaning Tower. This status and appeal comes from the campanile’s lack of vertical equilibrium, which forces visitors to confront the axis-mundi. It’s a unique tension that’s rooted in verticality.

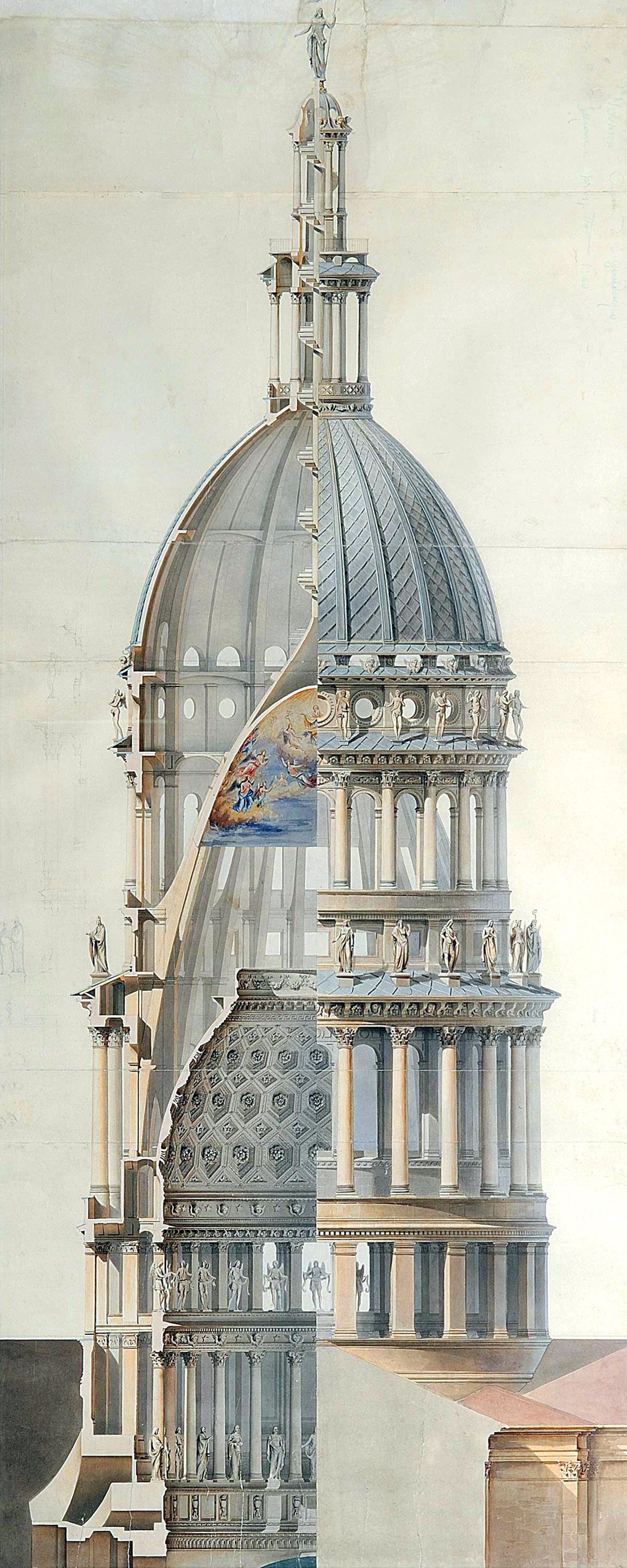

Alessandro Antonelli’s Basilica of San Gaudenzio

Pictured above is an elevation of the Basilica of San Gaudenzio in Novara, Italy. The building features an elaborate dome and cupola structure. This structure appears to be on steroids, with quite a few stacked-forms below and above the dome itself. It seems over-built compared to the building it caps, and it’s overtly vertical design is a statement from the architect regarding the power of verticality.

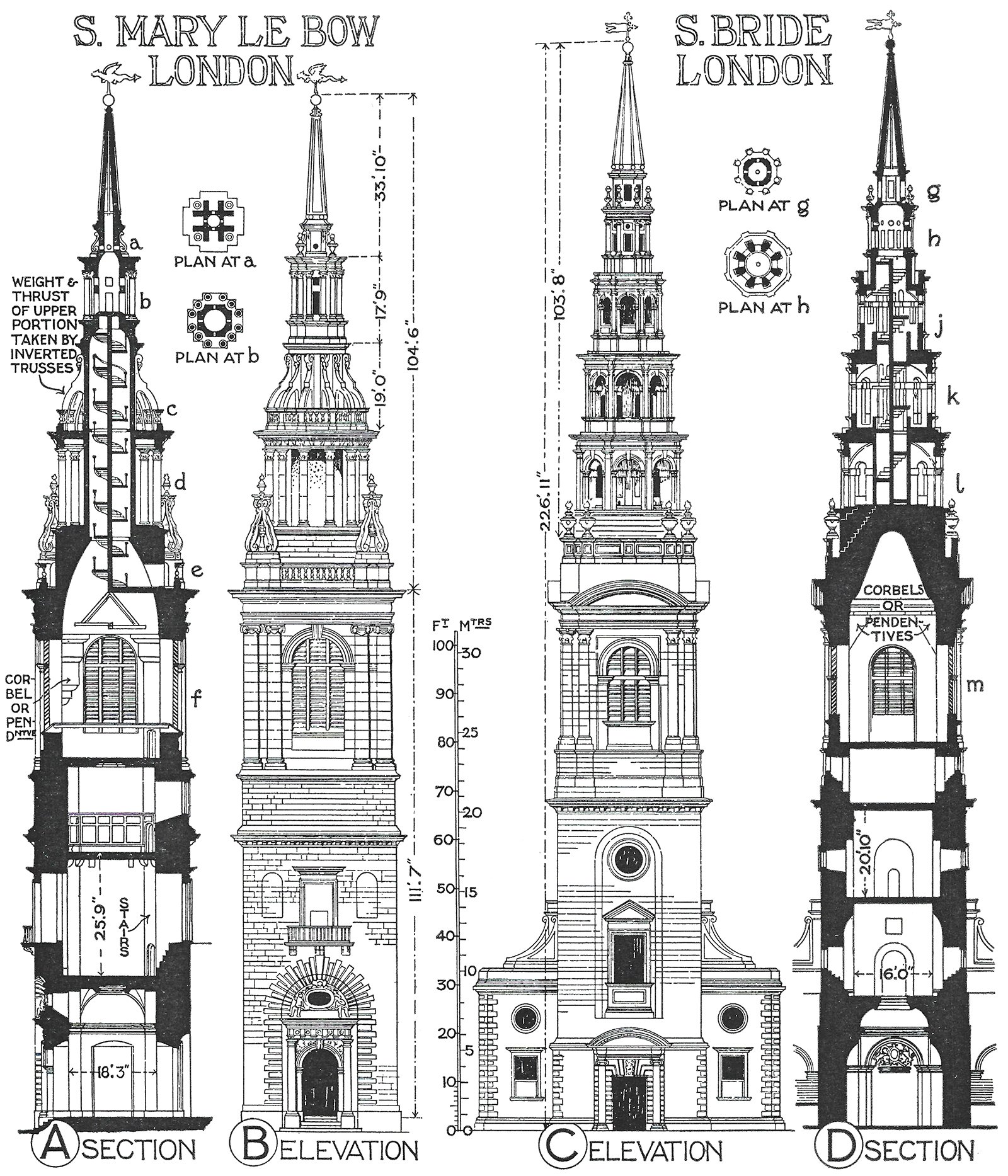

Sir Christopher Wren’s Church Steeples

Sir Christopher Wren was an English architect best known for his Renaissance and Baroque church designs that commonly featured conspicuous steeple designs. Pictured above are drawings of two such examples. These steeples are massive in scale, and they dwarf their adjacent church buildings. This mismatch of scales suggests that Wren considered these towers to be much more important than the churches they accompany. Through their height, Wren was using verticality to announce the presence of his buildings.

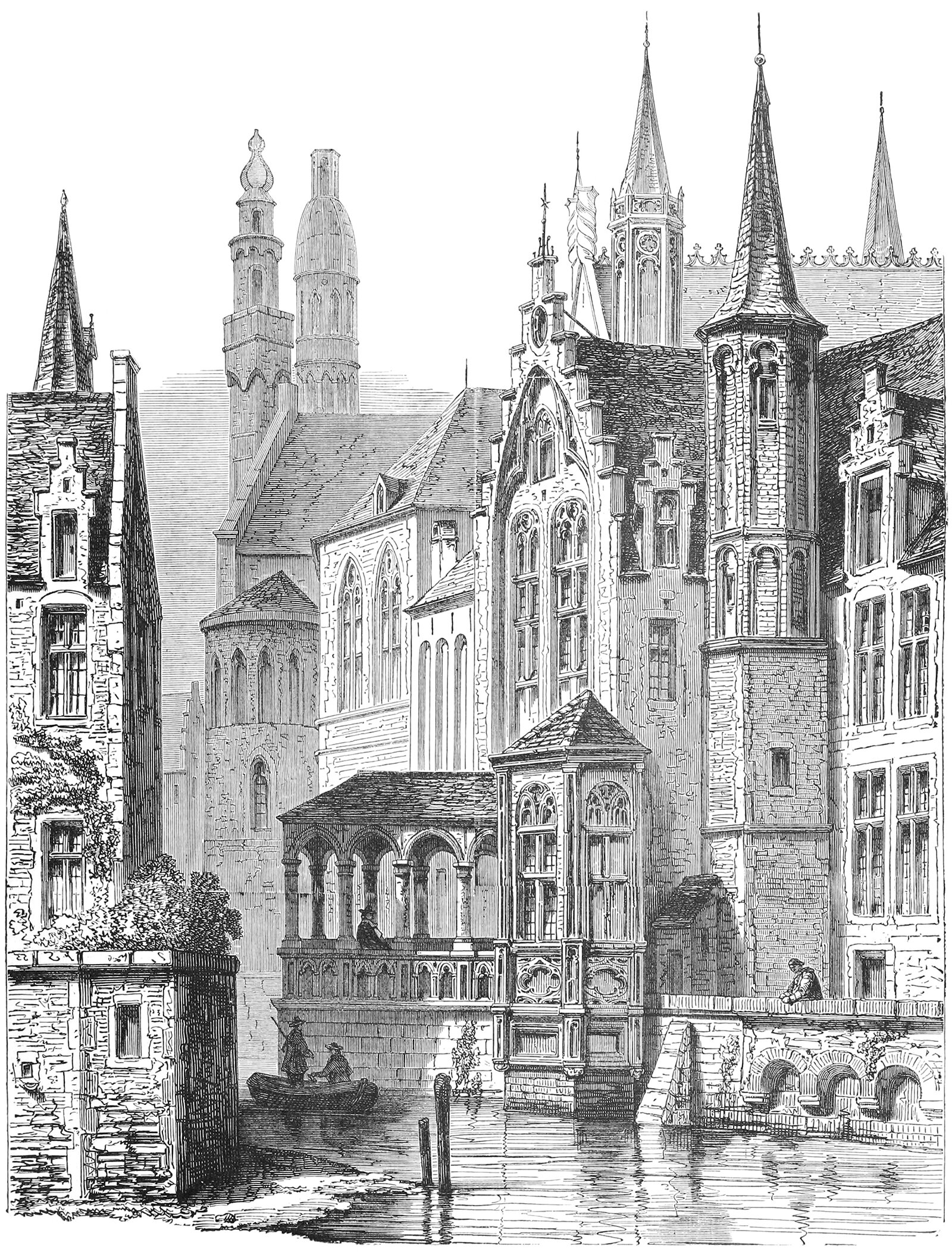

The Vertical Townscape

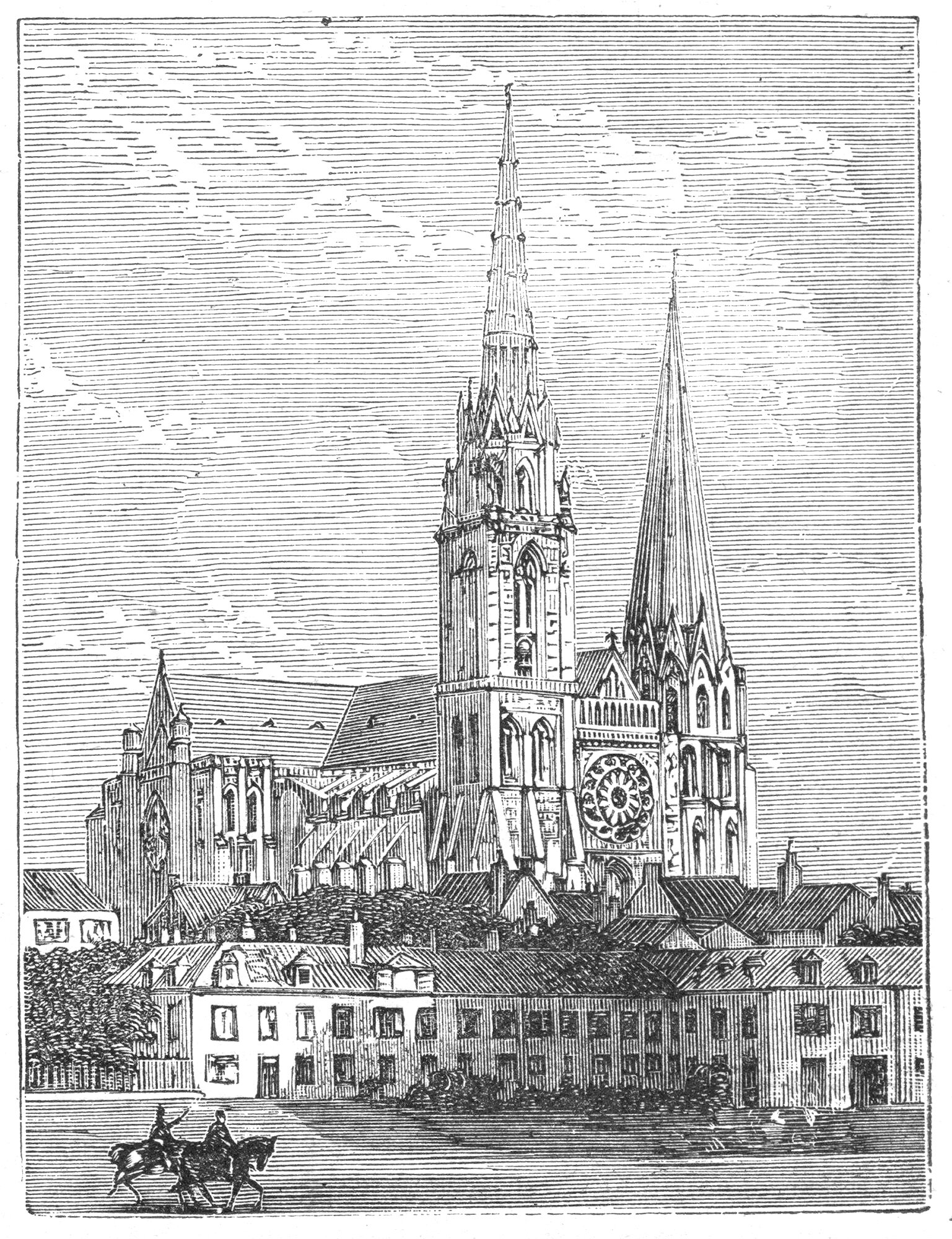

I came across this illustration recently, and I was immediately struck by it. It was drawn in 1880 and shows a medieval canal in Bruges, Belgium. What struck me was how the entire townscape seems to reach upward toward the sky. The scene is an amalgamation of turrets, towers and pinnacles, and the effect is a forest of brick and wood with each part jockeying for position on the skyline.

The Évreux Belfry

Pictured above is an illustration from 1825 showing a streetscape in Évreux, France. It was drawn by Richard P. Bonington, and it focuses on the town belfry, which was built from 1490-1497. Bonington does a great job of showing how a tower like this can dominate a streetscape, even if it isn’t that tall by today’s standards.

Leonardo da Vinci’s Saint John the Baptist

This is Leonardo da Vinci’s painting Saint John the Baptist, painted near the end of da Vinci’s life and career, sometime around 1515. It shows the saint, dimly lit against a dark background and gesturing with his right hand up to the sky. His upward gesture is the focus of the work, since his arm is the closest to the frame, and also the brightest part.

Raphael’s School of Athens and The Duality of Verticality

One of Raphael’s most famous works is his School of Athens fresco at the Stanze di Raffaello in the Vatican. The painting, completed in 1511, shows key historical figures of philosophy, with Plato and Aristotle located at the center (pictured above). The two central figures are in dialogue about their respective beliefs, with Plato pointing up toward the sky and Aristotle holding his hand down, gesturing toward the space around them. This duality of gestures runs core to the field of philosophy, and it also runs core to the theory of Verticality.

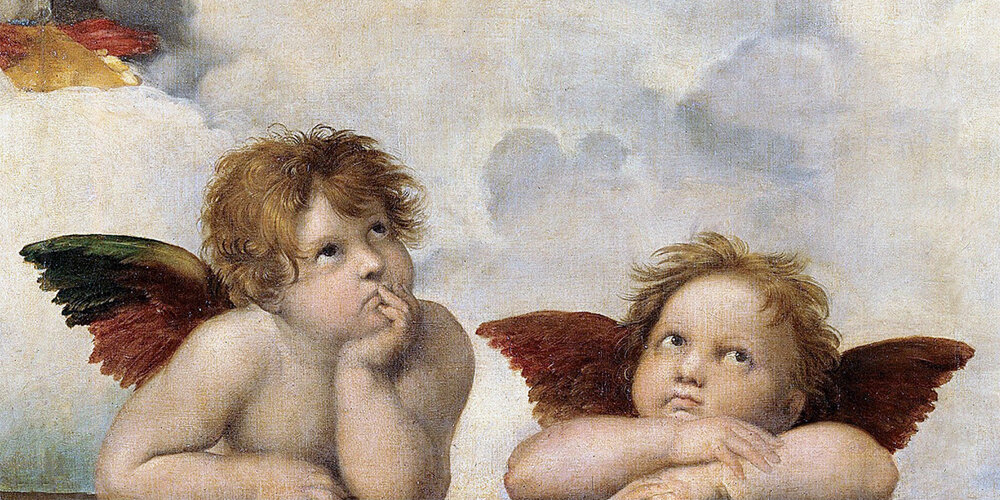

The Two Cherubs

For nearly all of human history, the space above our heads represented the unknown. Our ancestors would look up in awe, longing to satiate the innate need within us for Verticality. The two little cherubs pictured above encapsulate this innate need to escape the Earth’s surface, and their resulting fame apart from the painting they inhabit serves to illustrate this.

Verticality, Part VIII: God versus Ego

The human world becomes as important as the world of God

The rise of Christianity in the Western world would have profound effects on the built environment and human culture. Two major threads would combine to influence Early Christian architecture and culture. The first is the architecture of the Ancient Romans, who were already wrestling with Verticality. The second is the Book of Genesis and its central theme of Heaven (the above) and Hell (the below). Combine these two, and you get an ongoing battle between God and Ego that would see some of the most impressive structures of all time get built.