Welcome to On Verticality. This blog explores the innate human need to escape the surface of the earth, and our struggles to do so throughout history. If you’re new here, a good place to start is the Theory of Verticality section or the Introduction to Verticality. If you want to receive updates on what’s new with the blog, you can use the Subscribe page to sign up. Thanks for visiting!

Click to filter posts by the three main subjects for the blog : Architecture, Flight and Mountains.

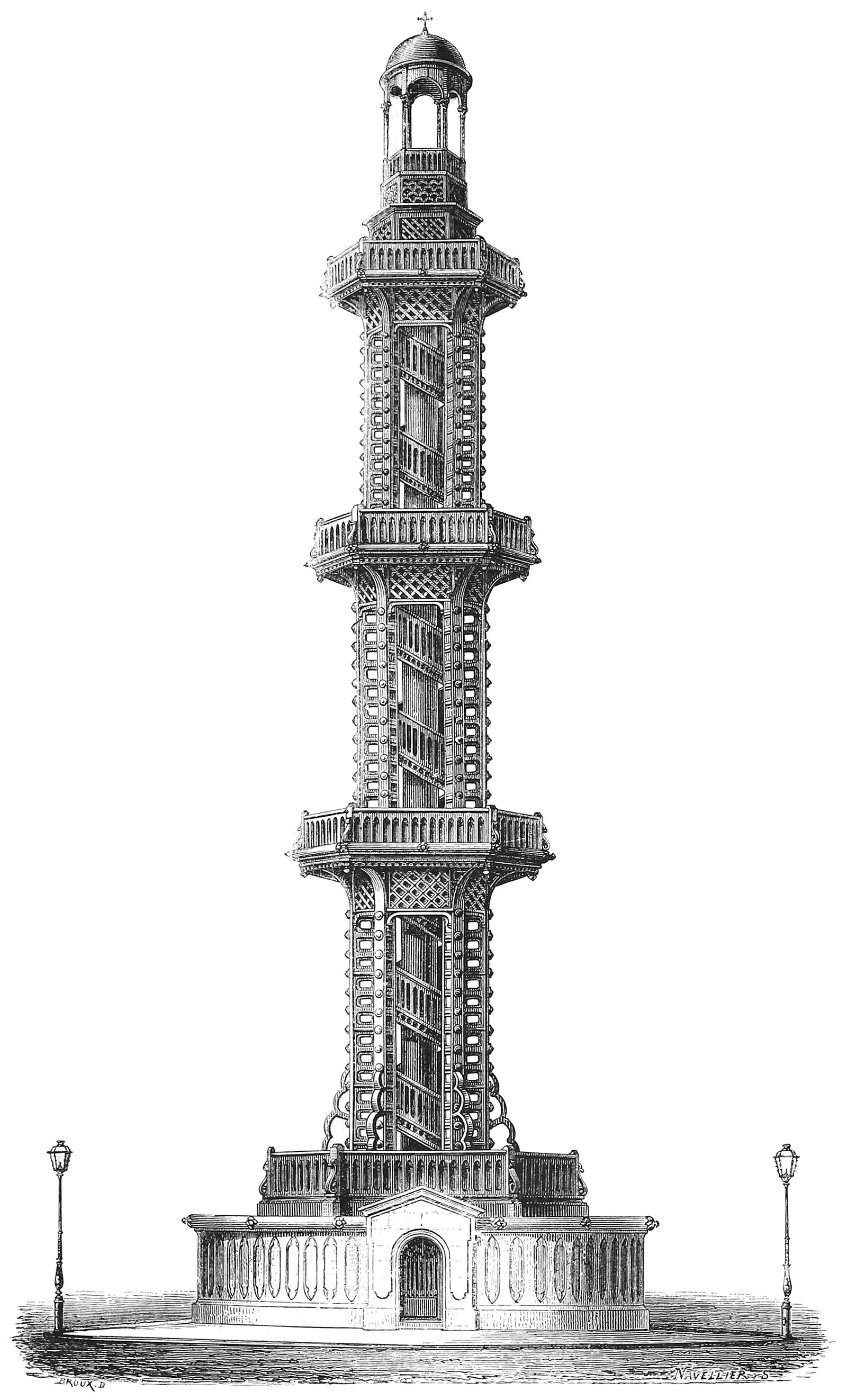

The Grenelle Artesian Well of Paris

Pictured above is the Grenelle Artesian Well in Paris, built from 1834 to 1841. During these seven years, an 8-inch diameter hole was drilled to a depth of roughly 550 meters (1,800 feet) below the earth’s surface. This process of construction took place far below ground, but in the end the well was marked with a 42 meter (138 feet) tower and fountain, placed a block away from the well itself. The tower was a deft mixture of uses, including a fountain, a sculpture, and an observation deck.

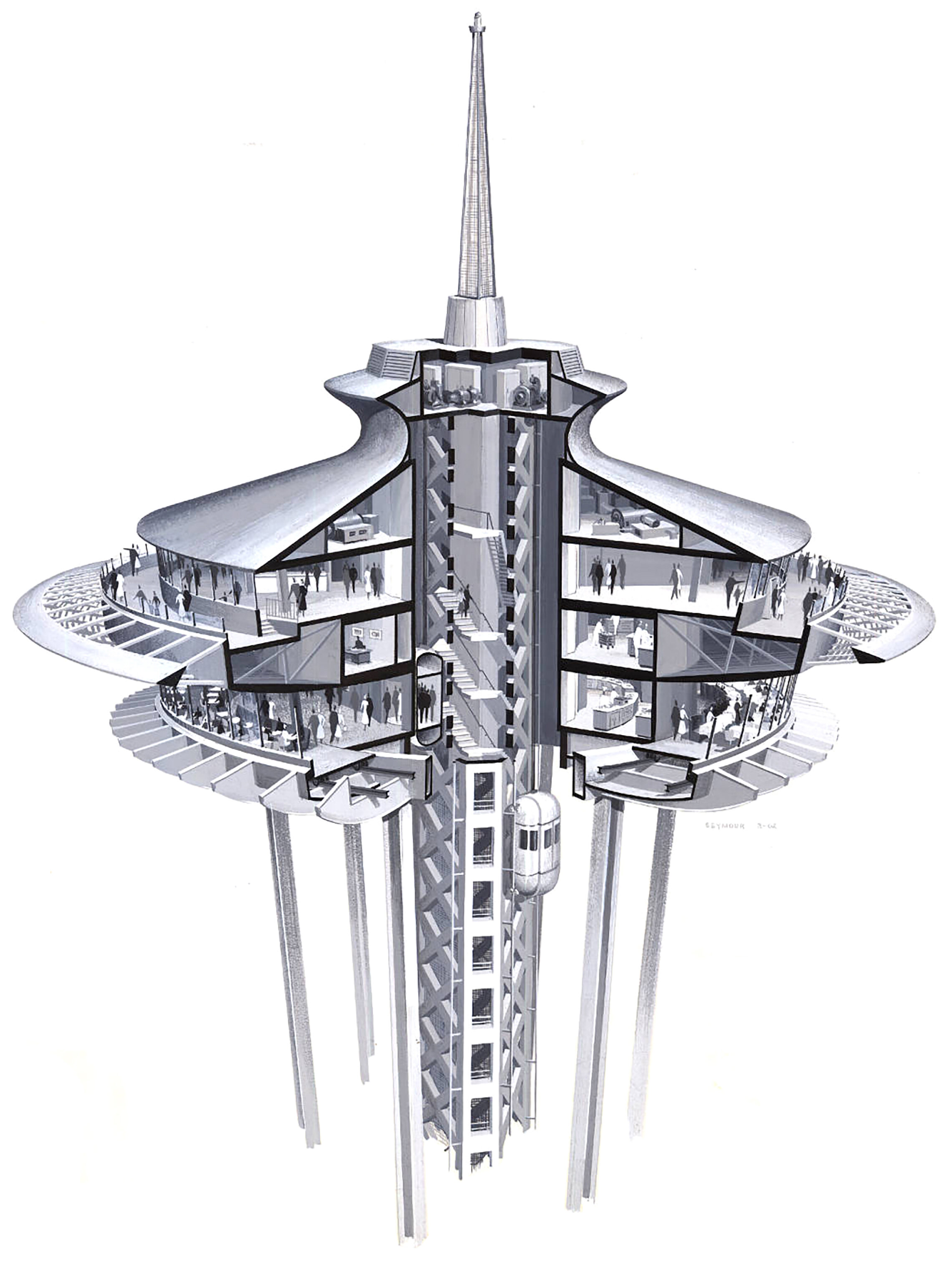

The Seattle Space Needle and Uninterrupted Verticality

I recently visited the Space Needle while on a trip to Seattle, and the experience was a masterful example of uninterrupted verticality. Throughout the entire visit, I had visual access to my surroundings, and this made the experience much more meaningful than a typical observation tower or skydeck. This is because the lift experience is normally buried deep inside a building, so it doesn’t have views to the outside. This severs the experience of verticality and abstracts the act of ascension and descension. Not the case at the Space Needle, however, and it was fantastic.

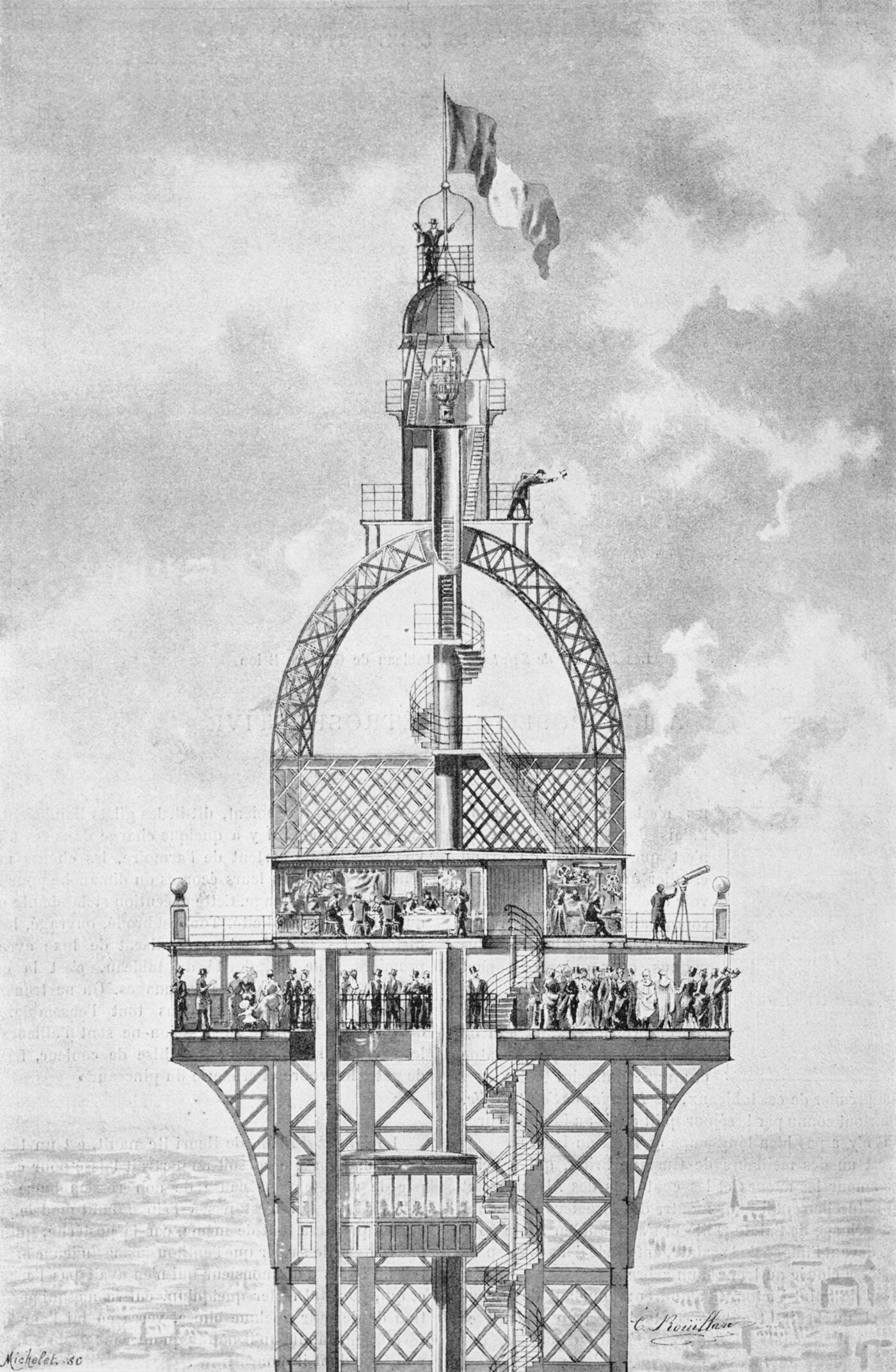

The Secret Apartment at the Top of the Eiffel Tower

Pictured above is an illustration of the Eiffel Tower’s original crown design. You can see the main observation deck, which is packed with people, all enjoying the view atop the tallest building in the world. Unbeknownst to them, however, is the private apartment located on the floor just above them. It was designed by and for Gustave Eiffel as a private space for himself to entertain notable guests and perform scientific experiments. It’s generally referred to as the secret apartment, but it was fairly well-known to the public that Eiffel built the space for himself.

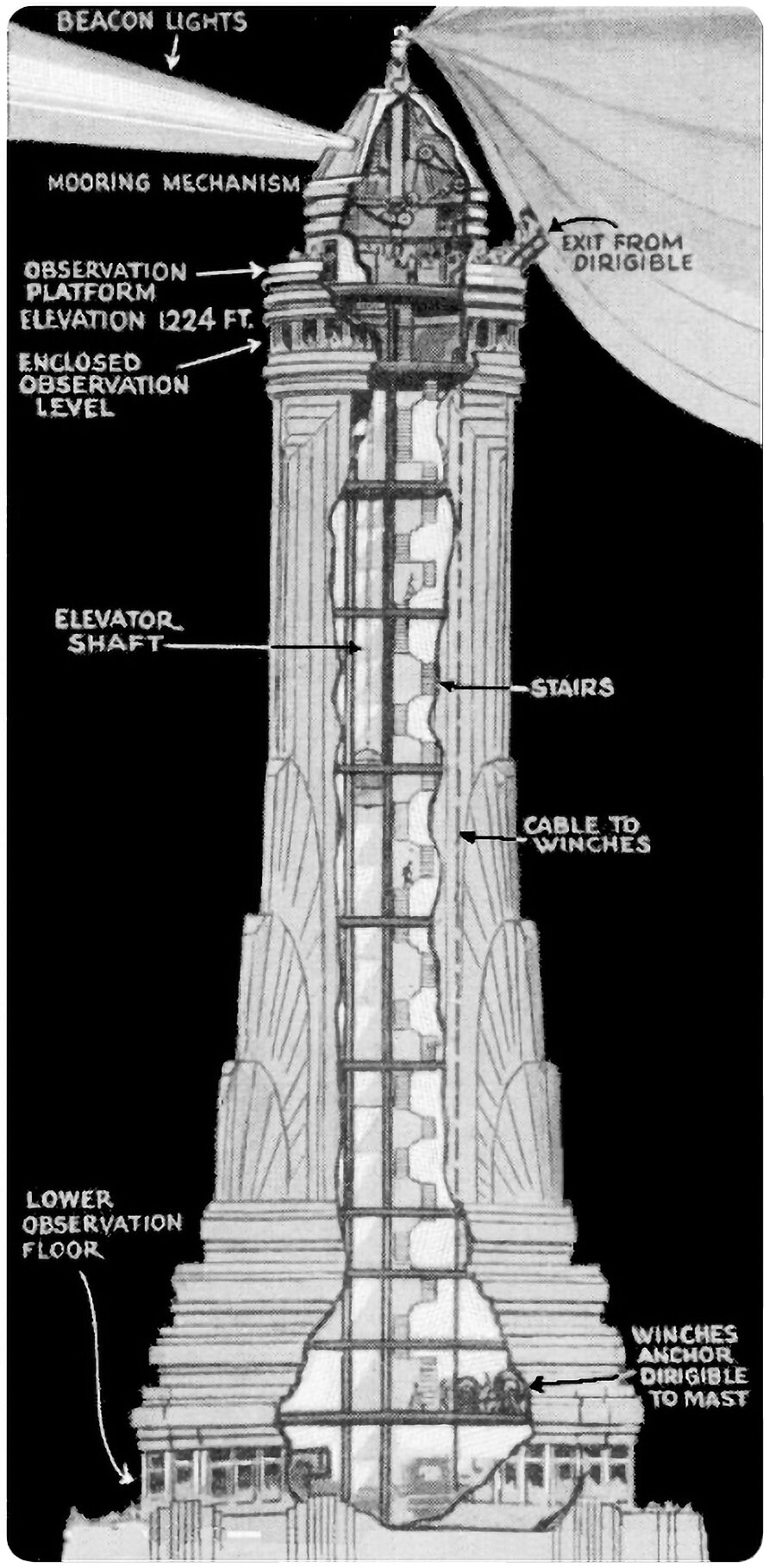

The Empire State Building’s Mooring Mast

Pictured above is an illustration from Popular Mechanics that shows the Empire State Building’s proposed mooring mast. This mast was designed to act as a dock for dirigibles, who could moor themselves to the top of the tower’s crown and load and unload passengers. It’s a wild idea, albeit completely impractical.

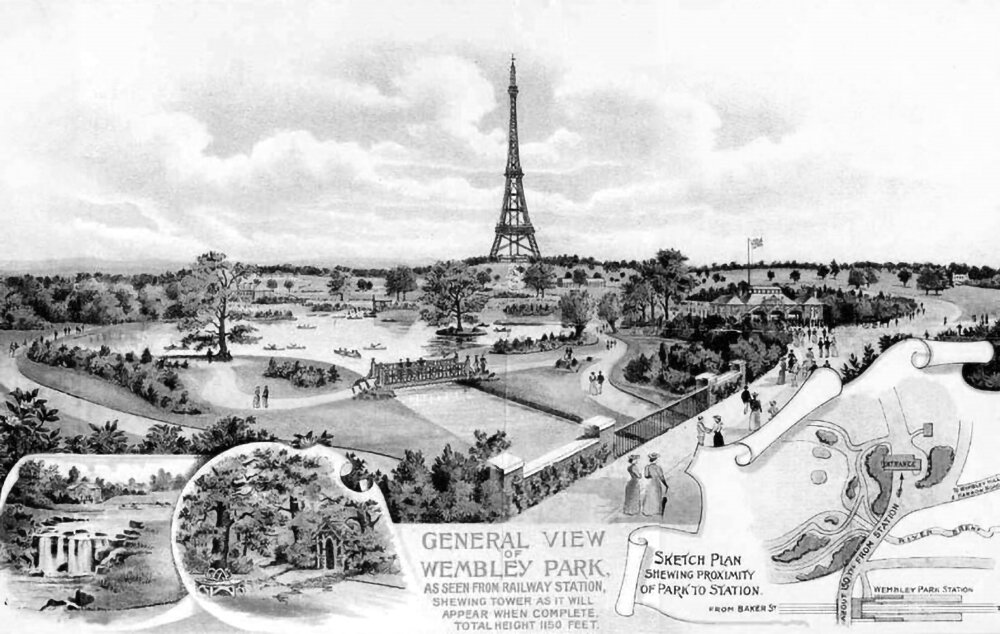

Alternate Realities : The Great Tower for London Competition

In 1890, an open competition was held to design the Great Tower for London in the soon-to-be-opened Wembley Park. The tower was to be the tallest in the world, and it would claim the title from the Eiffel Tower in Paris, completed the year before. An open competition was held, which received 68 submissions from all over the world. Together, these designs provide a rich cross-section of the world’s architectural taste at the time.

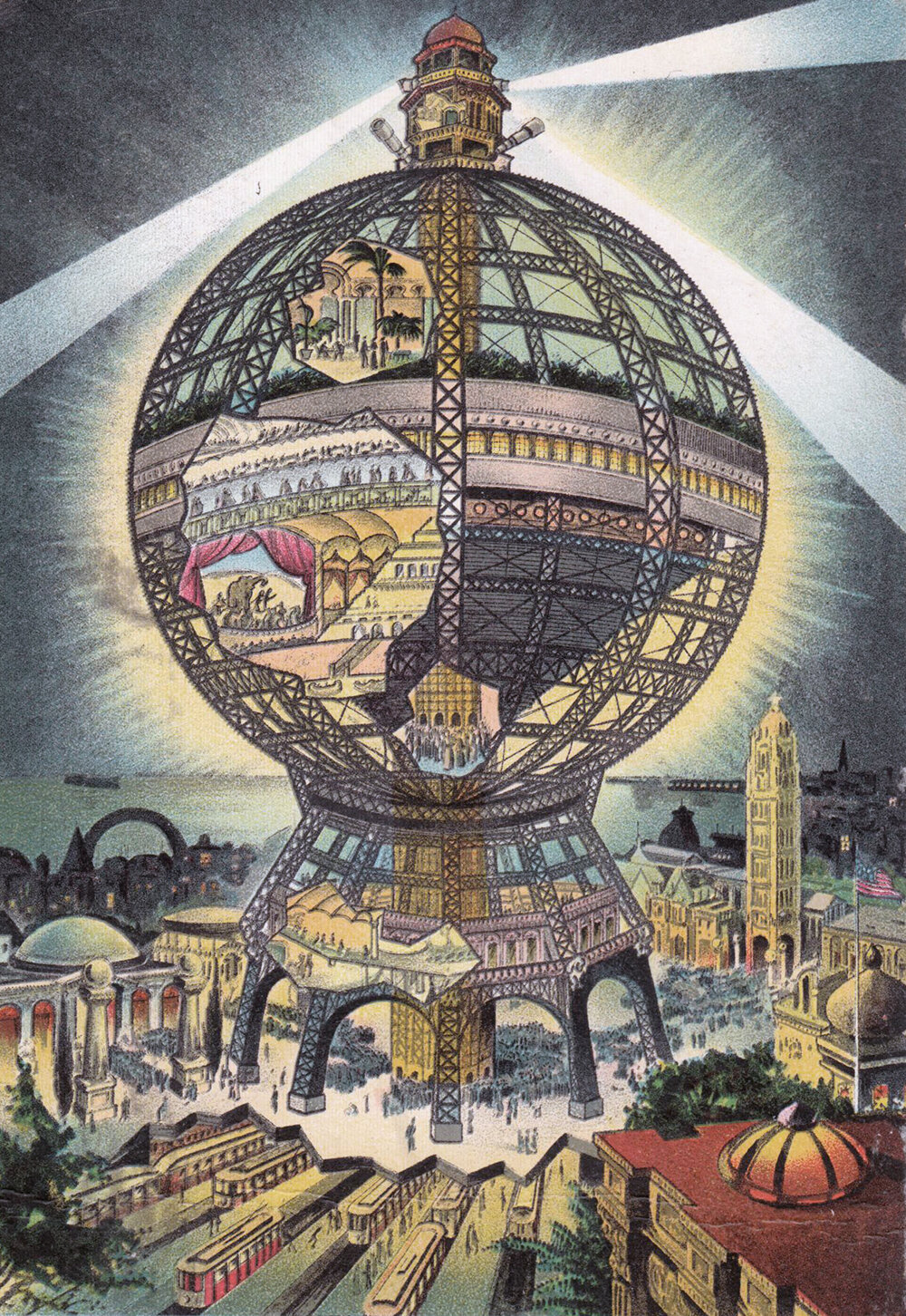

The Coney Island Globe Tower

Pictured above is the Coney Island Globe Tower, proposed in 1906 by Samuel Friede for a lot at the corner of Steeplechase Park in Coney Island, Brooklyn. The building features an enormous globe built of latticed steel, similar in style to the Eiffel Tower. The Globe was designed as an entertainment and leisure complex, and it was marketed as the second tallest building in the world, behind the aforementioned Eiffel Tower. The most intriguing part of the proposal, however, is that it was a fraud.

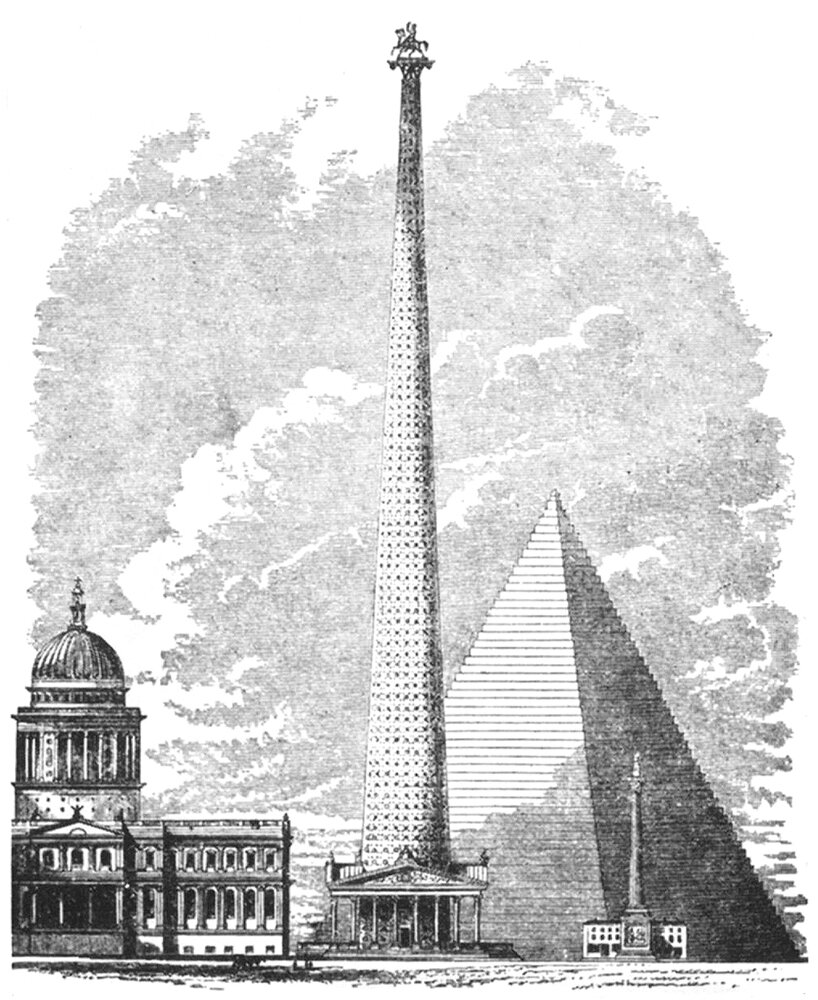

Richard Trevithick’s Monument to the Reform Act

This is Richard Trevithick’s Monument to the Reform Act, proposed in 1832 for a site somewhere in London. It was meant to be 1,000 feet (304 meters) tall, and it would’ve towered over the entire cityscape at the time. It’s one of a few tower proposals that aimed for the landmark 1,000-foot height, long before the Eiffel Tower made it a reality in 1889.

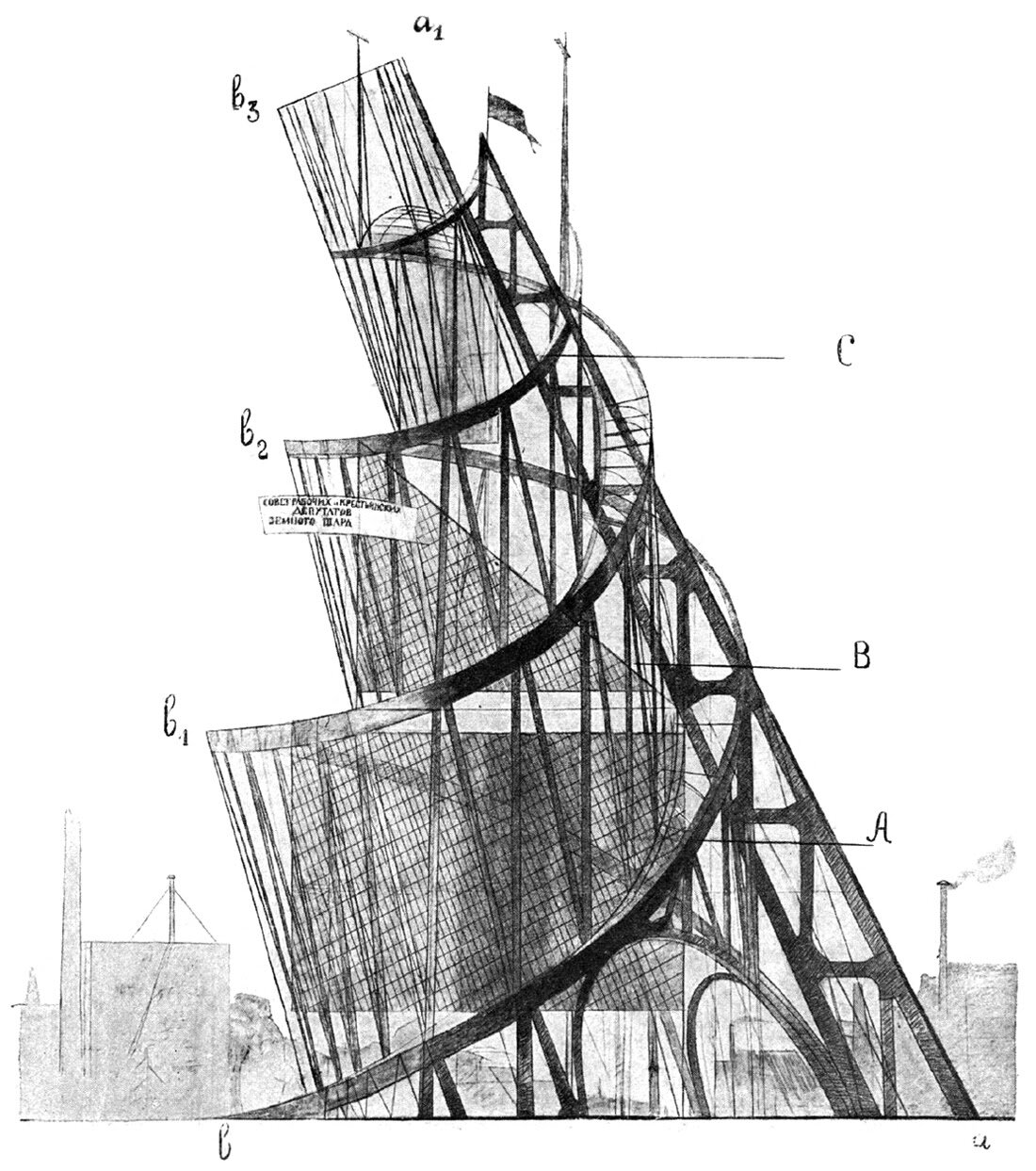

Vladimir Tatlin’s Tower

Tatlin’s Tower has always made me uneasy. There’s something about it’s form that rubs me the wrong way, but at the same time, it’s strangely captivating. In school, I was exposed to it many times in architecture history classes, but it was always glossed over as just another example of Russian Constructivism. Let’s take a closer look and see just how strange it is.

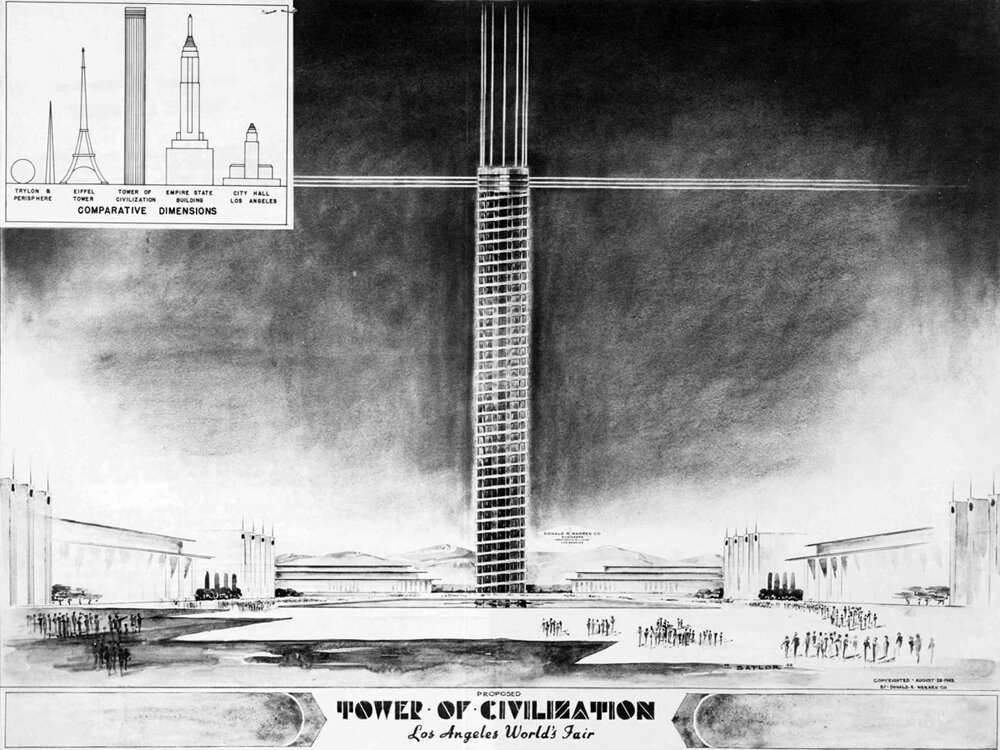

The Tower of Civilization

This is the proposed Tower of Civilization, designed by civil engineer Donald R. Warren for the planned, but never held, 1939 World’s Fair in Los Angeles. It would’ve been the centerpiece of the event and the tallest building in the world, coming in at 393 meters, or 1,290 feet tall. The tower was no doubt meant to signify the status of Los Angeles as a world-class city, and it used Verticality to do so.

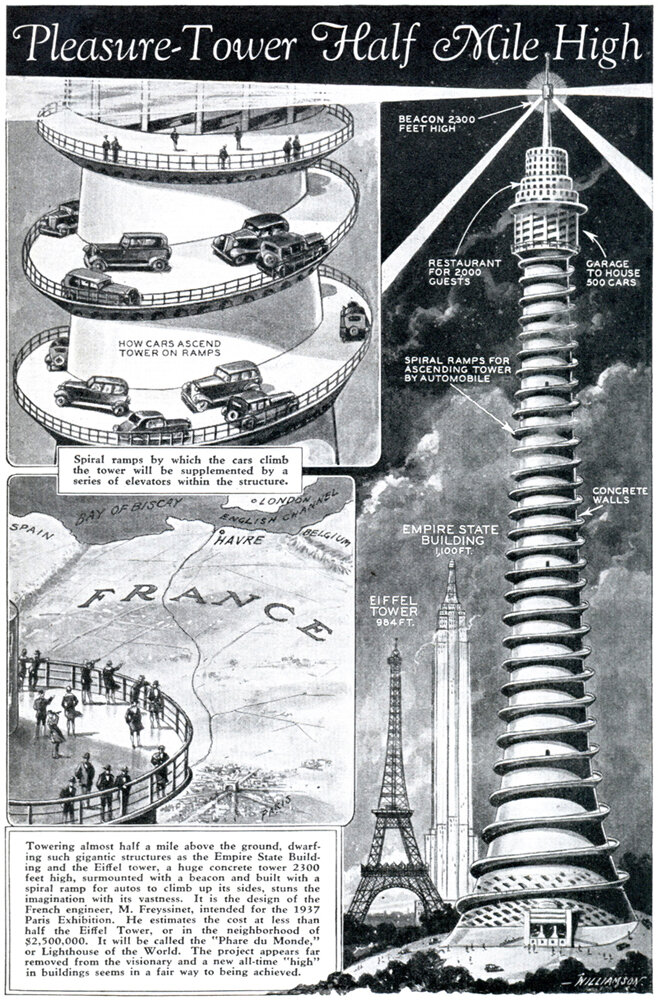

The Phare du Monde Pleasure Tower

Pictured above is a tower proposal from 1933 for the 1937 World’s Fair in Paris. It features an external spiral ramp leading to a parking garage 1640 feet (500 meters) from ground level.[2] Once at the top, visitors would find a restaurant, hotel and observation deck, and the spire contained a lighthouse beacon and a meteorological cabin. The view? Sublime. The design? Utterly ridiculous, unless taken as a satirical statement on civilization’s reliance on the automobile.

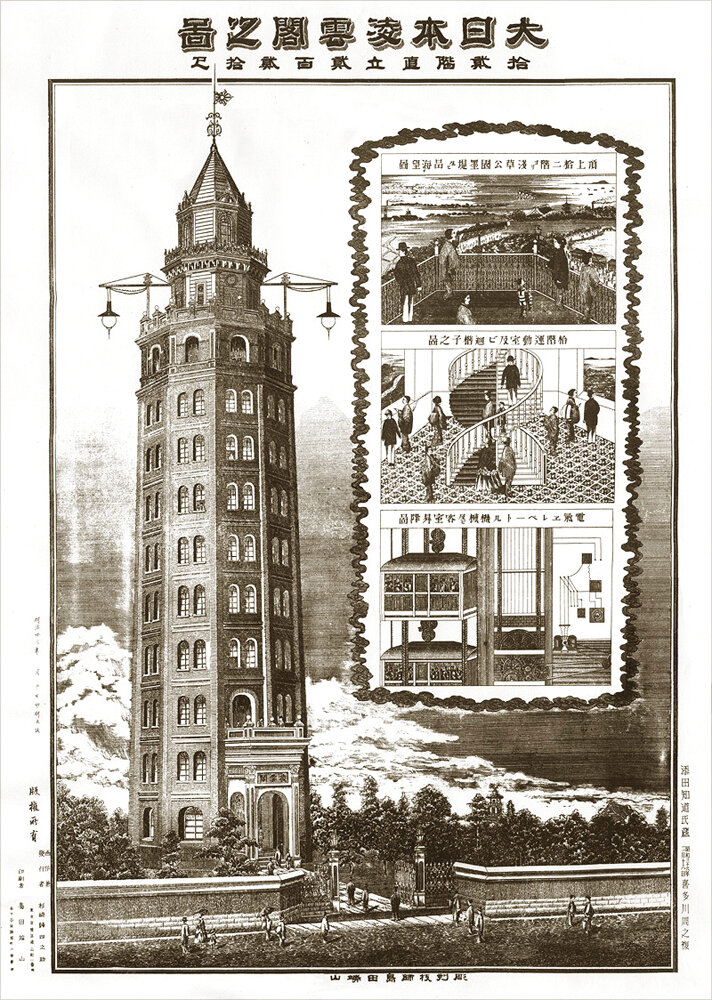

Ryōunkaku Tower: Japan's First Skyscraper

This is Ryōunkaku, Japan’s first western-style skyscraper. Built in 1890 in the Asakusa district of Tokyo, Ryōunkaku resembles a lighthouse, with an octagonal plan and a slight taper, topped with two setbacks and a pointed roof. The name Ryōunkaku translates to Cloud-Surpassing Tower, which indicates the importance of Verticality for the building’s landmark status.

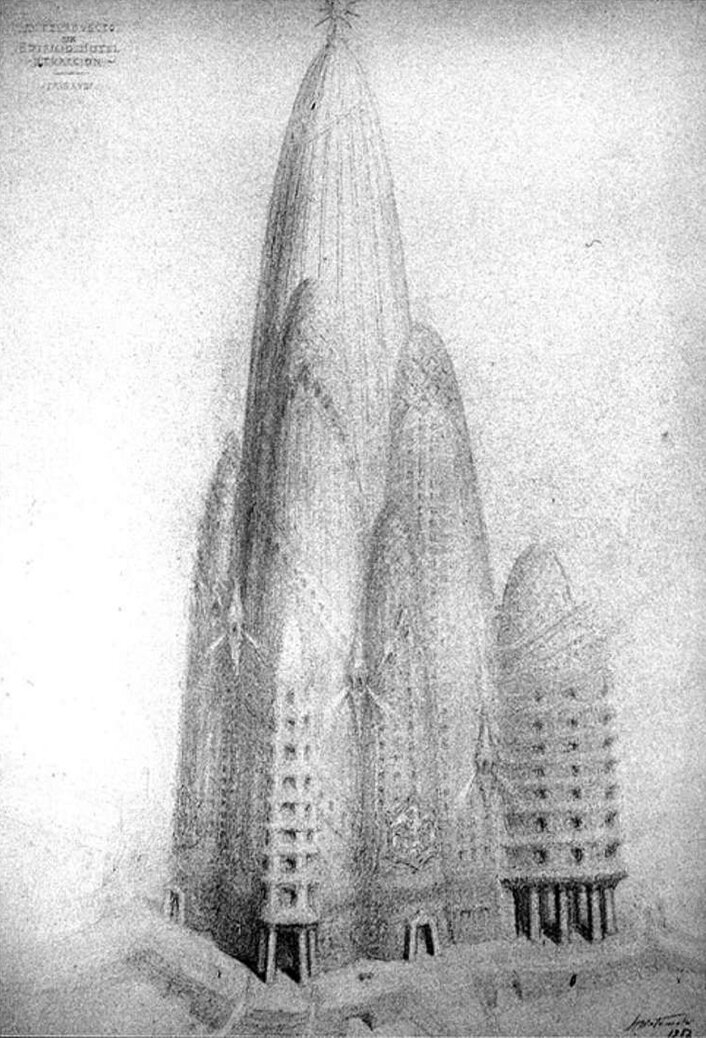

Antoni Gaudí's New York Skyscraper

The Spanish architect Antoni Gaudí is known the world over for his iconic architecture, rich in organic, curvilinear forms. One lesser-known project of his is the Hotel Attraction. It was designed in 1908 for an unspecified site in Lower Manhattan, New York City. The project would have housed a hotel, restaurants, theatre hall, exhibition hall, galleries, and a panoramic lookout at the top, called the 'Space Tower'. If built, it would have been 360 meters, or 1,181 feet tall.