Alternate Realities : The Great Tower for London Competition

Promotional illustration for Watkin’s Tower, showing a general view of Wembly Park and a sketch of the Wembly Park Station, which provided direct access to the park from the city. Watkin’s Tower is shown in the distance, commanding the landscape and providing a landmark for the park.

Architectural competitions are usually by invite only, meaning the client will ask a select list of architects to participate. Every so often, the client decides to open the competition up to anyone who fancies it. The most famous example of this is the Chicago Tribune Tower competition, held in 1922. A lesser-known example of this was the Great Tower for London competition, held in 1890.

Open competitions such as these, depending on their visibility, can attract dozens of submissions, which typically represent a cross-section of society’s architectural values at the time. In 1890, the public was enamored with the newly-constructed Eiffel Tower in Paris, which was completed the previous year. The English were keen to out-do the French, however, and wanted to claim the title of the world’s tallest building for themselves.

The competition was the brainchild of Sir Edward Watkin, a railroad entrepreneur who was working on a vision for an amusement park just outside London, on the land occupied by Wembley Park today. His plan was to market the park as an escape from the city, and his railroad would carry people between the two. He needed a world-class attraction to bring in ticket sales, so he decided to build the world’s tallest building. His first course of action was to ask Gustave Eiffel to build it, but the Frenchman refused. Enter The Great Tower for London design competition.

The first and second place designs of the Great Tower for London Competition. First place went to Stewart, MacLaren and Dunn of London, and second place went to Webster and Haigh of Liverpool. The jury went with latticed designs that were Eiffel-esque, but were still unique enough to hold their own identity.

The popularity of the Eiffel Tower at the time cannot be understated. It had quickly become a global icon, representing Modernity and technological progress. Watkin knew this, and he was a great admirer of what Eiffel had achieved. A published account of the competition states this clearly: Taking into consideration the enormous popularity of the Eiffel Tower and the consequent pecuniary benefits conferred on those interested in that undertaking, it is not too much to anticipate that, in the course of a short time, every important country will possess its tall Tower.[1] Watkin wanted to be the man to give England her tall tower.

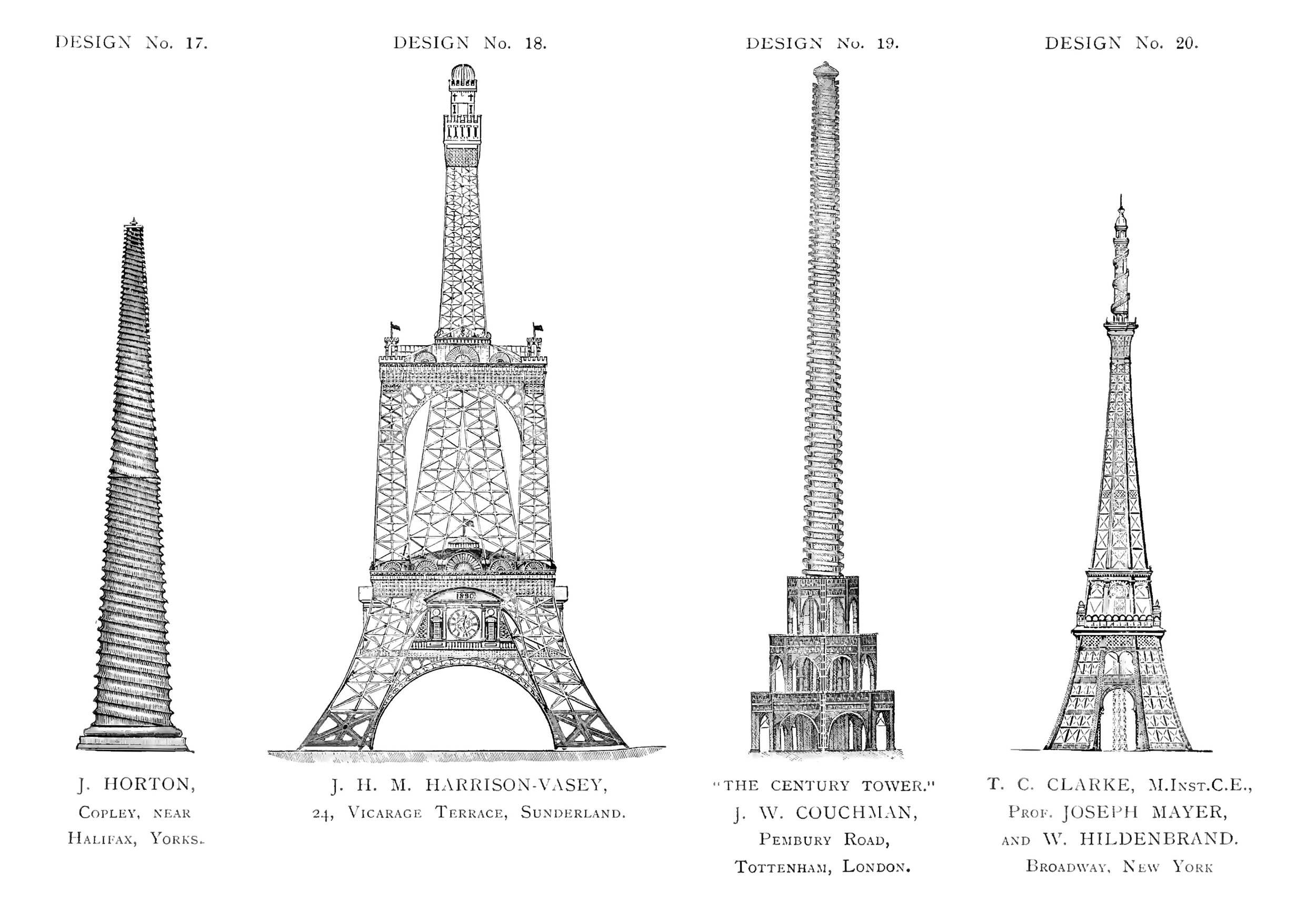

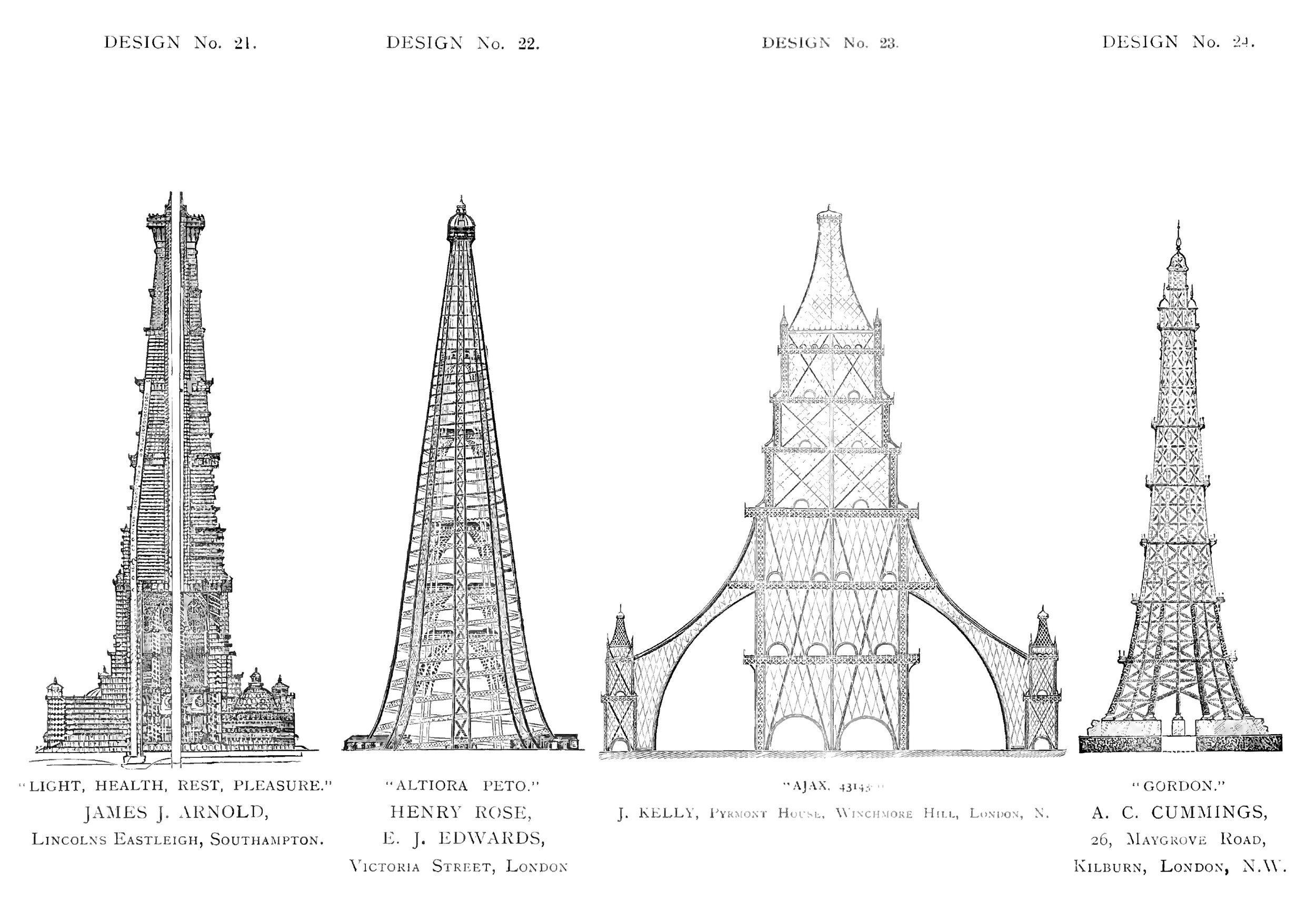

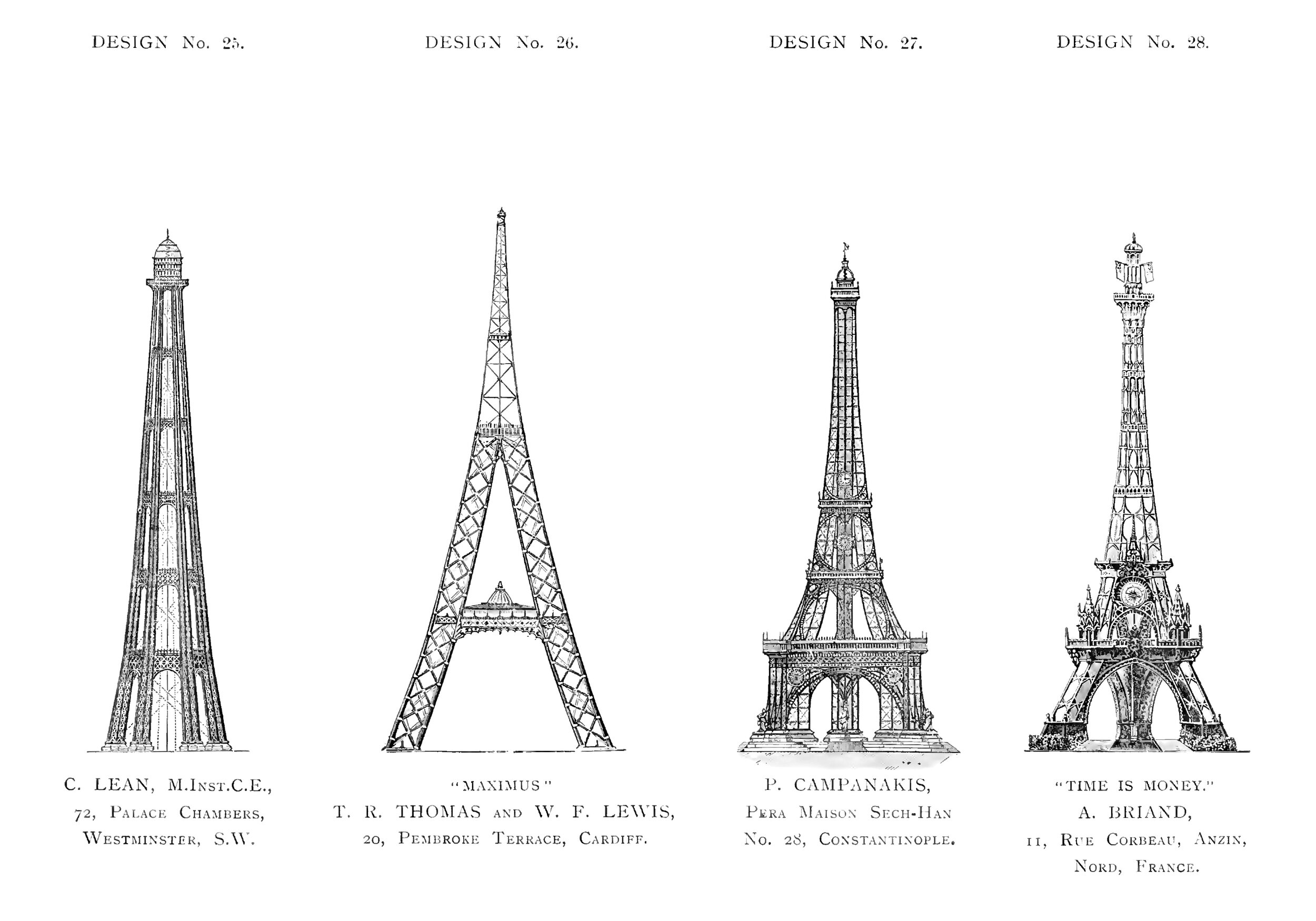

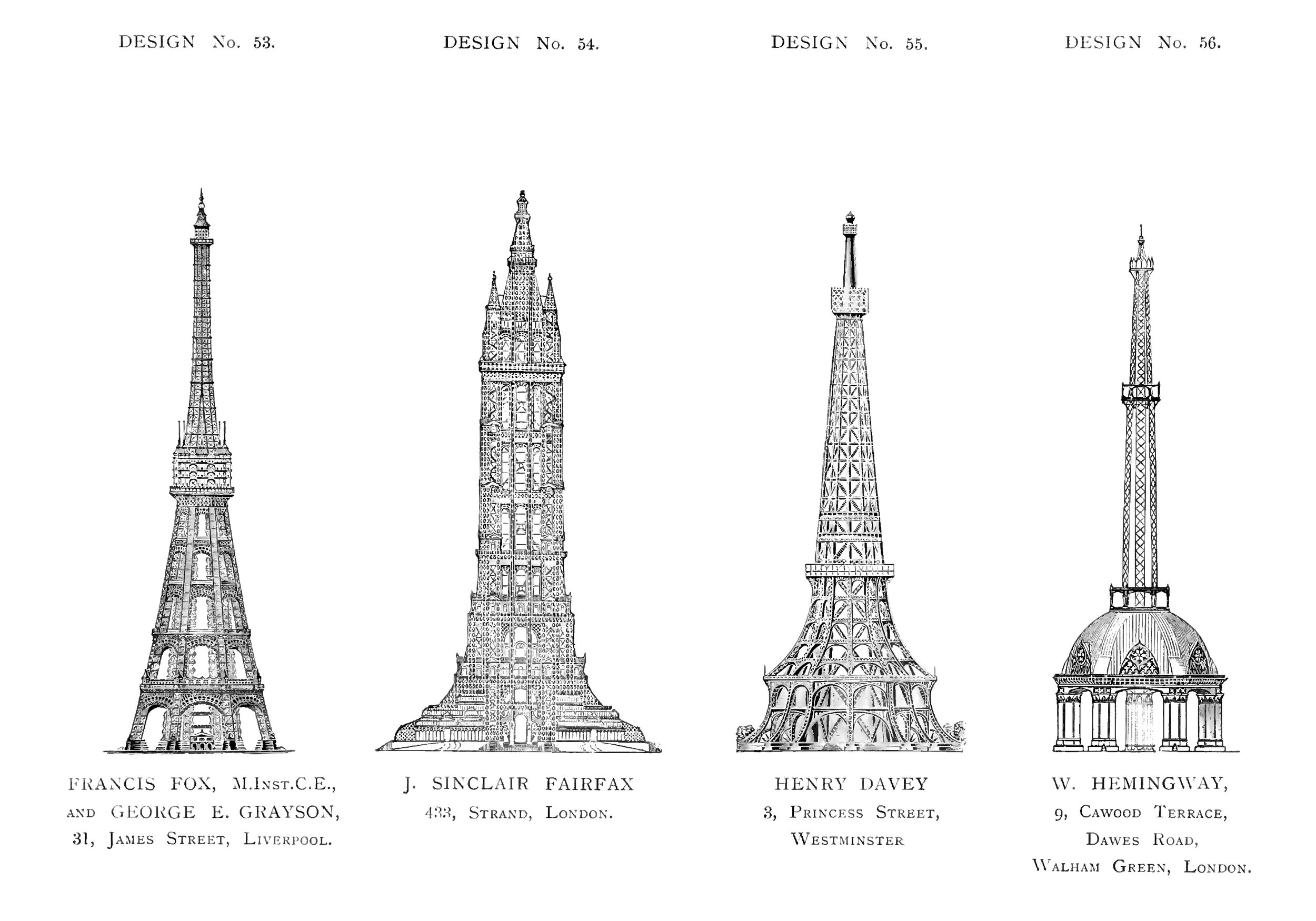

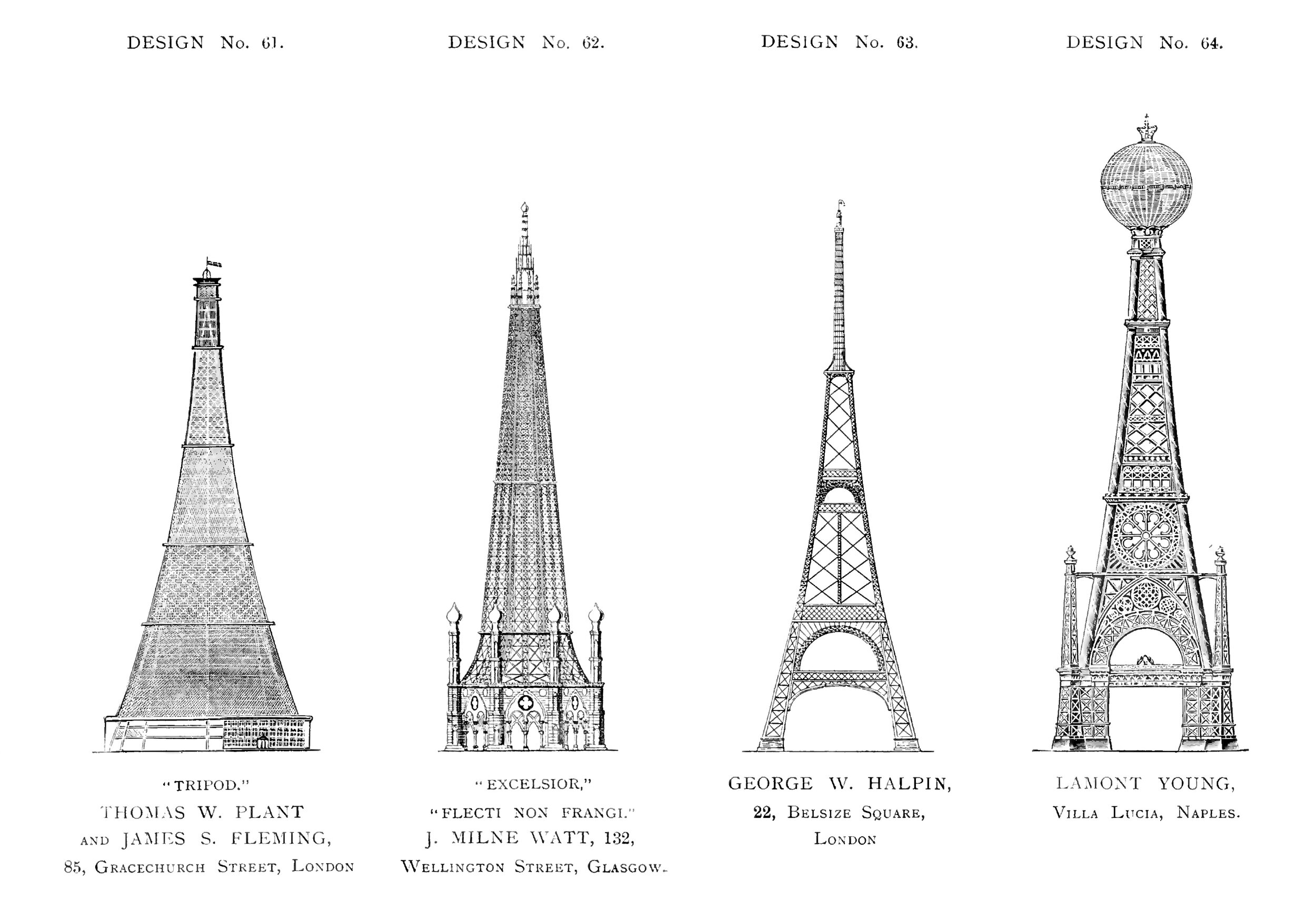

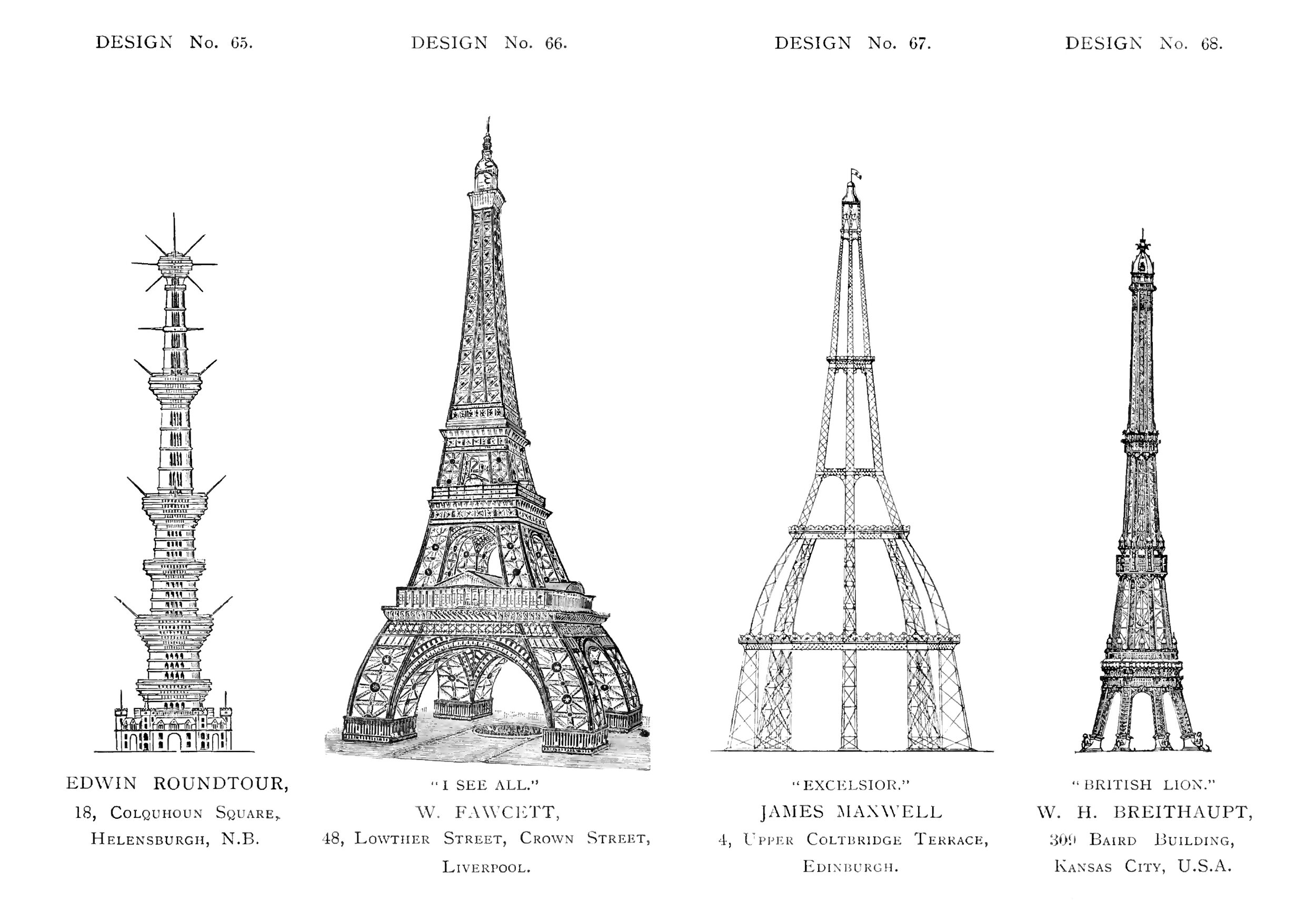

In total, the competition received 68 submissions, and they came in from all over the world. I’ve included all 68 designs below. It’s quite an eclectic bunch, and overall, the influence of the Eiffel Tower on the contestants is clear. After receiving all the submissions, Watkin held an exhibition to drum up public interest, and held a jury selection to pick the winner. The jury chose the two latticed designs pictured above; they were indeed Eiffel-esque, but were still unique enough to hold their own identity. First place went to Stewart, MacLaren and Dunn of London, and second place went to Webster and Haigh of Liverpool. Both have quite similar latticed-tower elements, however Stewart, MacLaren and Dunn continued their latticework down to the ground, while Webster and Haigh perched their tower atop a massive base of more traditional means.

Here’s the full lot of submissions:

After the winners were announced, Watkin hired civil engineer Benjamin Baker to oversee construction. The design was subsequently modified from the competition submission, and the final design appears below, alongside an illustration of the Eiffel Tower for a size comparison. Unlike the competition, which was called The Great Tower for London, this structure is generally called Watkin’s Tower. There were a few notable adjustments to the original design; the original eight-legged tower was reduced to a four-legged scheme, and the no-frills structuralism of the original was given flourishes of ornament at each terrace and at the crown.

Height comparison between Watkin’s Tower and the Eiffel Tower. Watkin’s Tower was meant to be 350.5 meters (1,150 feet) tall, which is 300 meters (984 feet). Illustration originally appeared in an 1894 issue of The Graphic.[2]

Construction began in 1892, and the tower’s first stage was completed in September 1895. Pictured below, the four legs are clearly visible, and one can get a sense of scale next to the trees in the foreground. Unfortunately, this was as far as the construction would get. Progress had been drifting behind schedule, and the foundations had begun to sink. They were designed for the original eight-legged scheme, and the reduction to four legs had put much more weight on half the points, which was too much for the original foundation to bear. In addition, Watkin had retired due to ill health, and the project stalled out after financing had dried up.

Photograph showing the incomplete tower, taken sometime between 1899 and the structure’s demolition in 1904.

The unfinished structure sat in the park for a few years before it was demolished, beginning in 1904. It’s a sad end to Watkin’s vision of the tower, but his park, which had opened in 1894, was quite successful as an escape from the city, just as Watkin had hoped. It’s a testament to the difficulties involved with building a structure this tall, and it serves to enhance our appreciation for the ones that get built successfully.

Watkin’s Tower remains an oft-forgotten piece of architectural history, but there’s much we can learn from the story. Captured within the 68 submissions is a rich cross-section of the world’s architectural taste at the time. It clearly illustrates the global influence of the Eiffel Tower, and it’s further evidence toward the human need for verticality that such a massive effort would be undertaken by the English in order to out-do the French in height.

Check out other unbuilt designs here.

[1]: Lynde, Fred C.. Descriptive Illustrated Catalogue of the Sixty-eight Competitive Designs for the Great Tower of London. London: Industries, 1890. 3-9.

[2]: “The Tower at Wembly.” In The Graphic, vol. 49 (14 April 1894). 422.

![Height comparison between Watkin’s Tower and the Eiffel Tower. Watkin’s Tower was meant to be 350.5 meters (1,150 feet) tall, which is 300 meters (984 feet). Illustration originally appeared in an 1894 issue of The Graphic.[2]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5e1e5ef4c84b953ac52564ba/1612024048392-SLCZC6I65G5EDT2TKD2A/1894-GreatTowerForLondon-SizeComparison.jpg)