Welcome to On Verticality. This blog explores the innate human need to escape the surface of the earth, and our struggles to do so throughout history. If you’re new here, a good place to start is the Theory of Verticality section or the Introduction to Verticality. If you want to receive updates on what’s new with the blog, you can use the Subscribe page to sign up. Thanks for visiting!

Click to filter posts by the three main subjects for the blog : Architecture, Flight and Mountains.

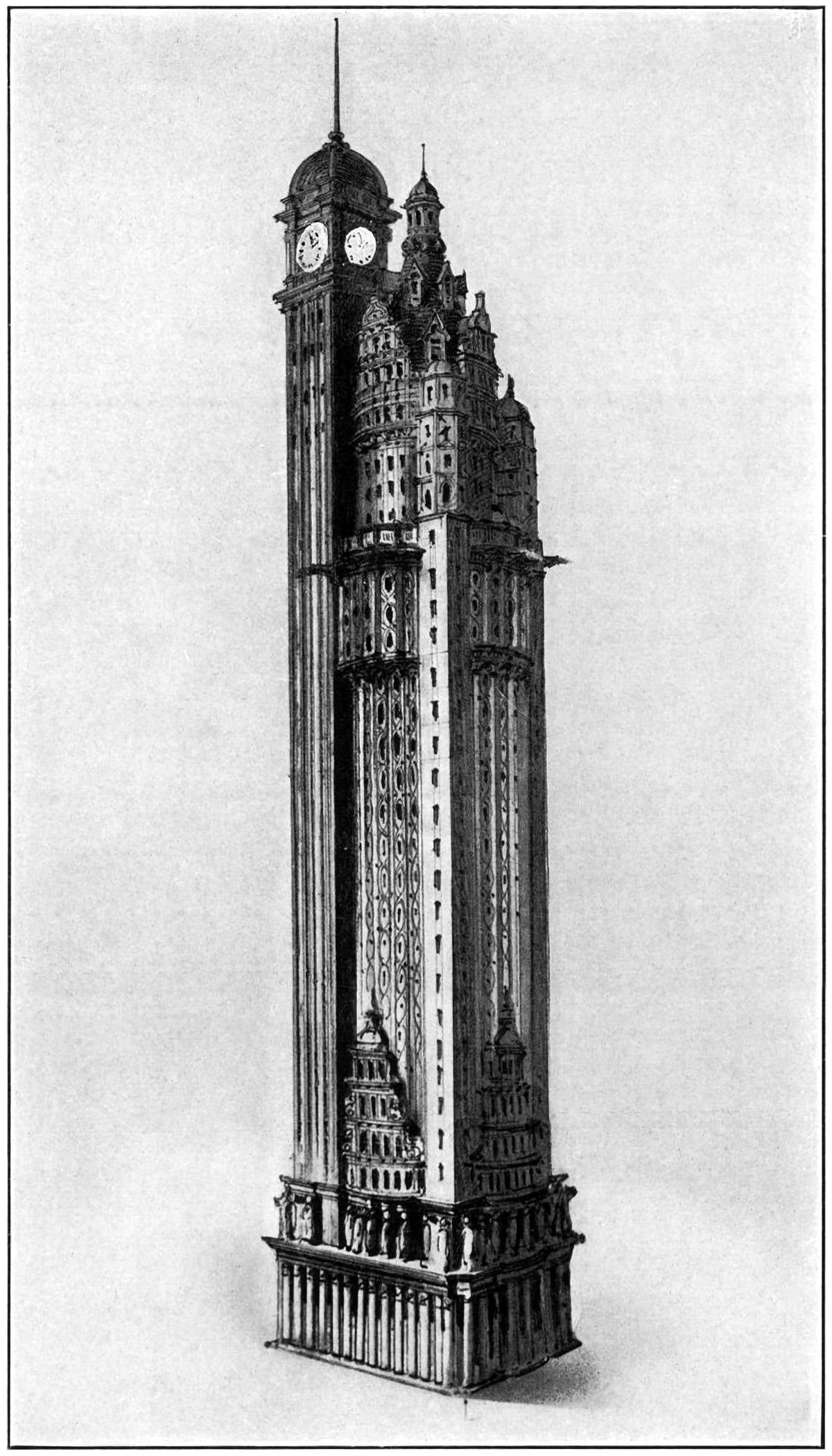

Lamb and Seddon’s Imperial Monumental Tower at Westminster

Pictured above is a 1904 proposal for an Imperial Monumental Hall and Tower in London. It was proposed by architects Edward Beckitt Lamb and John Pollard Seddon. The main feature of the proposal was a 167 meter (548 foot) Gothic tower, which dominates the entire site and its surroundings. It’s an ambitious proposal, and it uses verticality to elevate the monumentality of the site in three ways.

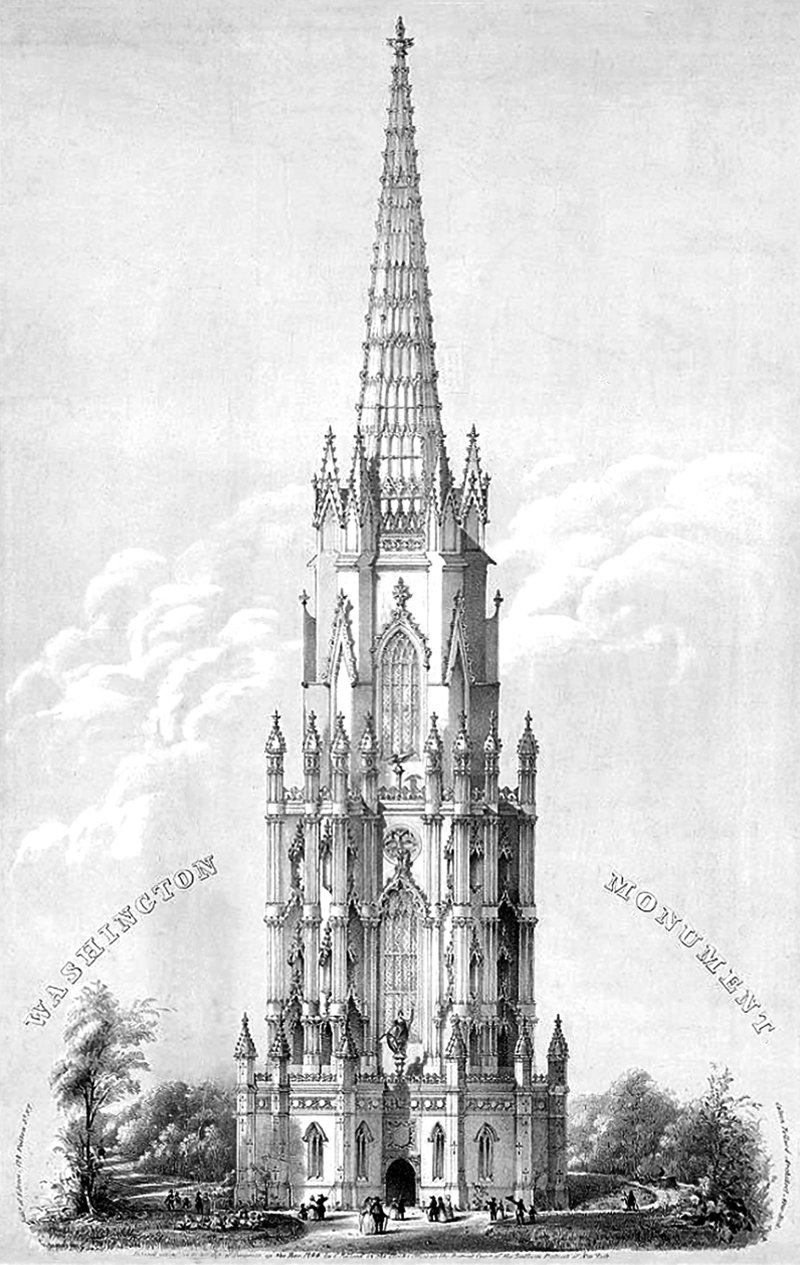

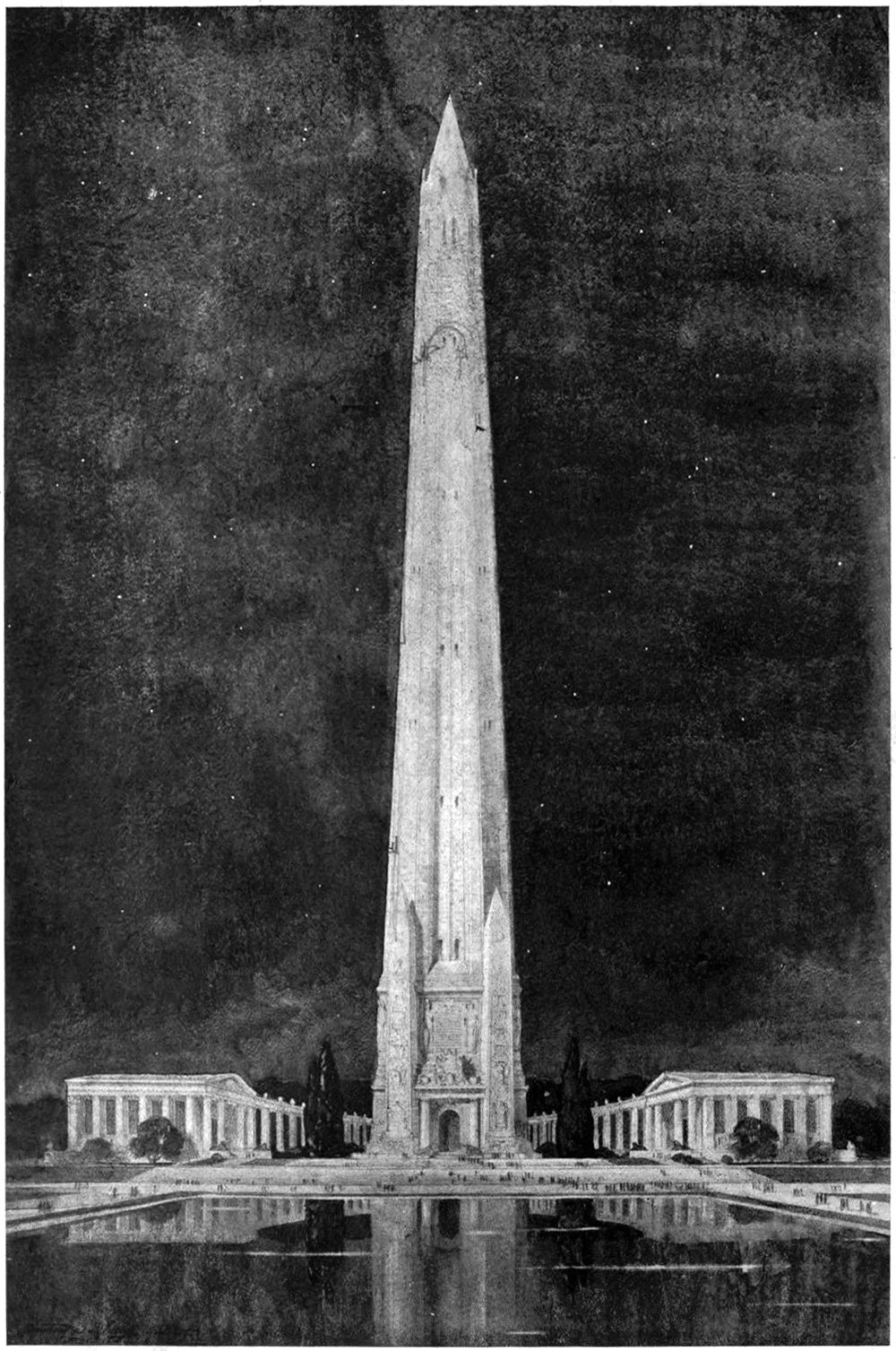

Alternate Realities : The Washington Monument

Pictured above is a proposal for the Washington Monument, designed by Robert Mills sometime around 1845. It was the winning entry of a design competition established in 1835 by the Washington National Monument Society. This design is the second of three structures that Robert Mills proposed or built for a monument to G.W., and each is based on verticality in some way.

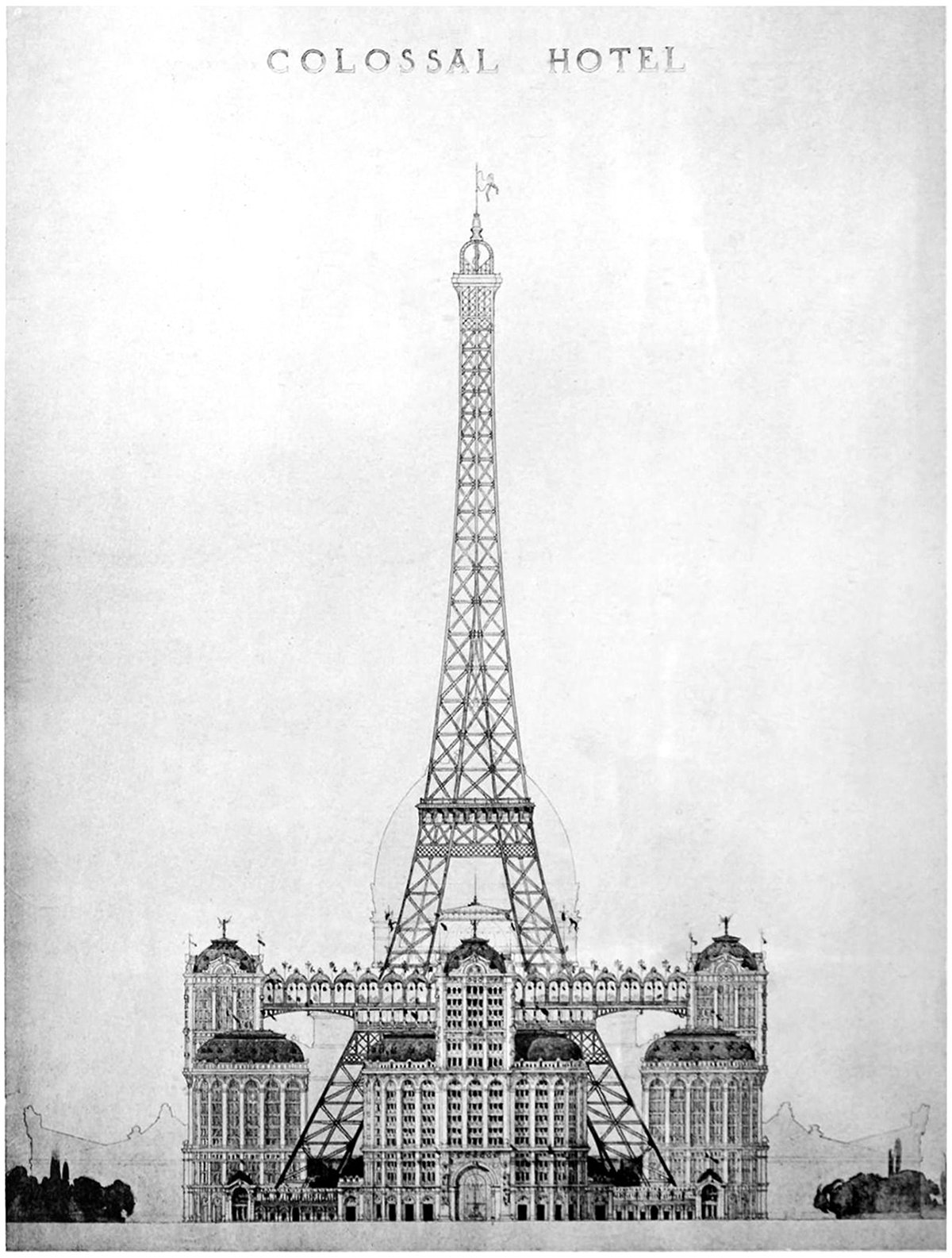

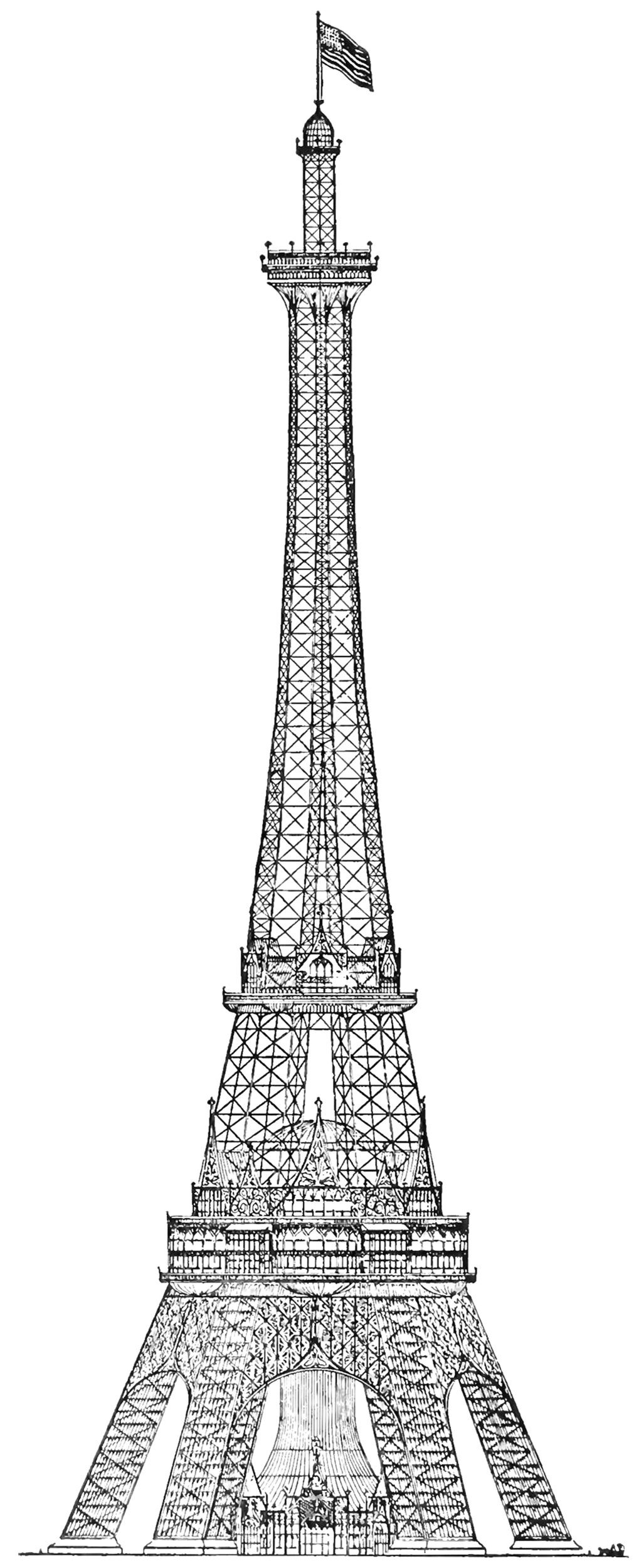

Alternate Realities : A Colossal Hotel at the Eiffel Tower

Pictured here is a proposal to put a colossal hotel at the base of the Eiffel Tower. It was proposed as part of the 1900 World’s Fair, called the Exposition Universelle, but it never got built. This elevation is the only drawing we have, which makes sense because most people who see the drawing would dismiss it immediately. The idea of filling up the void under the structure would destroy much of the Eiffel’s charm.

Calvin Pollard’s Proposal for the Washington Monument

Daniel Burnham once said, make no small plans. This is especially true in New York City, and the proposal pictured above fits right into both these molds. It’s a proposal for a monument to George Washington, and it would’ve dwarfed the height of the next tallest building in the city at the time (and also the tallest building in the world), Trinity Church.

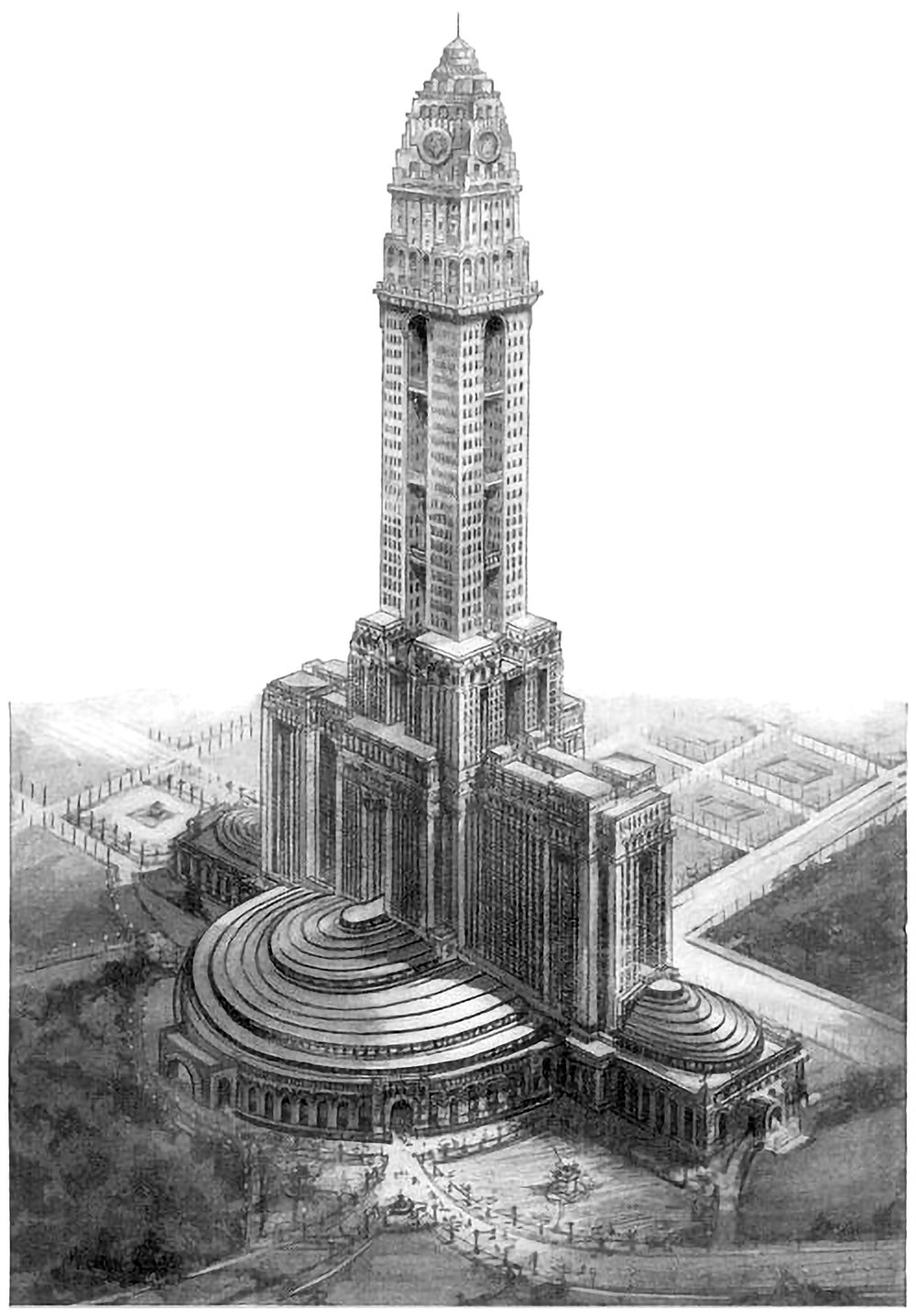

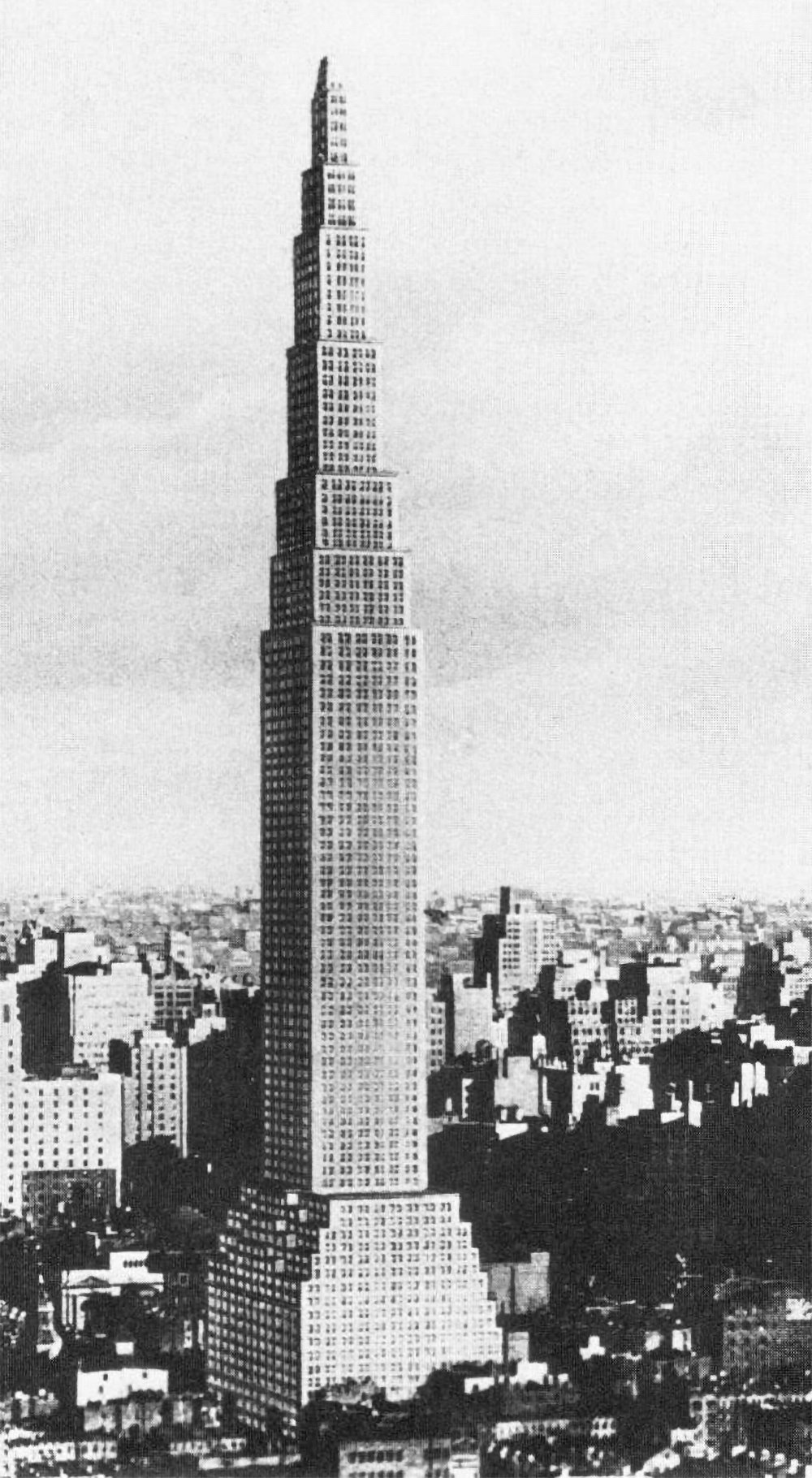

The Mole Littoria Project

Constructing the world’s tallest building is an act of politics just as much as an act of engineering. It’s a statement of accomplishment and power by all those involved. Paul Goldberger once wrote that you don’t build [the world’s tallest] skyscraper to house people, or to give tourists a view, or even, necessarily, to make a profit. You do it to make sure the world knows who you are. Pictured above is one example of this. It’s a 1924 proposal for the world’s tallest building, to be built in Rome. It was designed by Mario Palanti, who was an Italian architect who made his name in South America, and he proposed his design to Benito Mussolini, who enthusiastically approved the project.

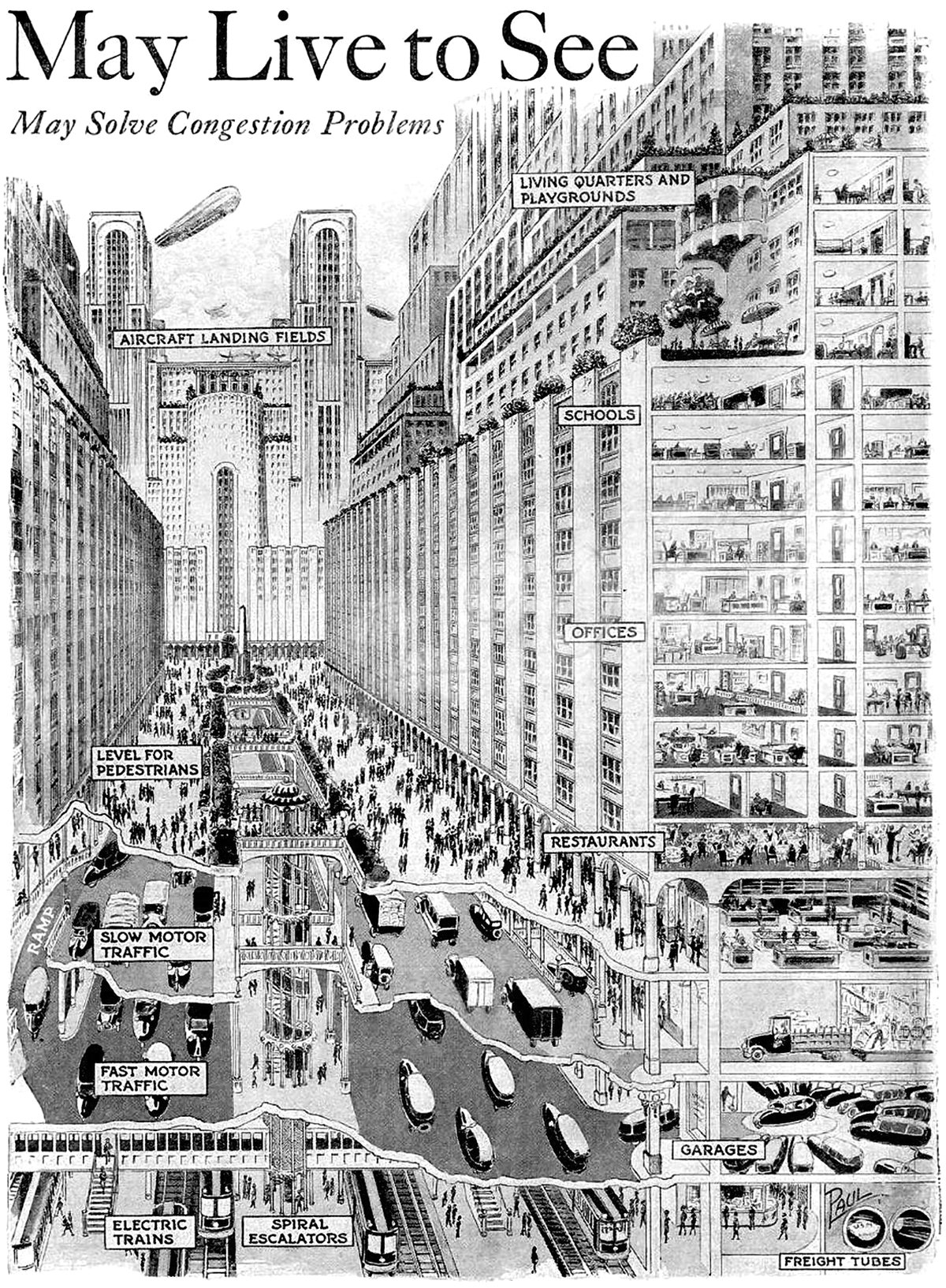

How You May Live and Travel in the City of 1950

Pictured above is a vision for a future city from 1925, which predicted what cities would look like in 1950. It’s quite an ambitious proposal, since it required sweeping urban changes to occur in only 25 years. The changes feature a vertical separation of city functions that start below the ground and end on top of skyscrapers.

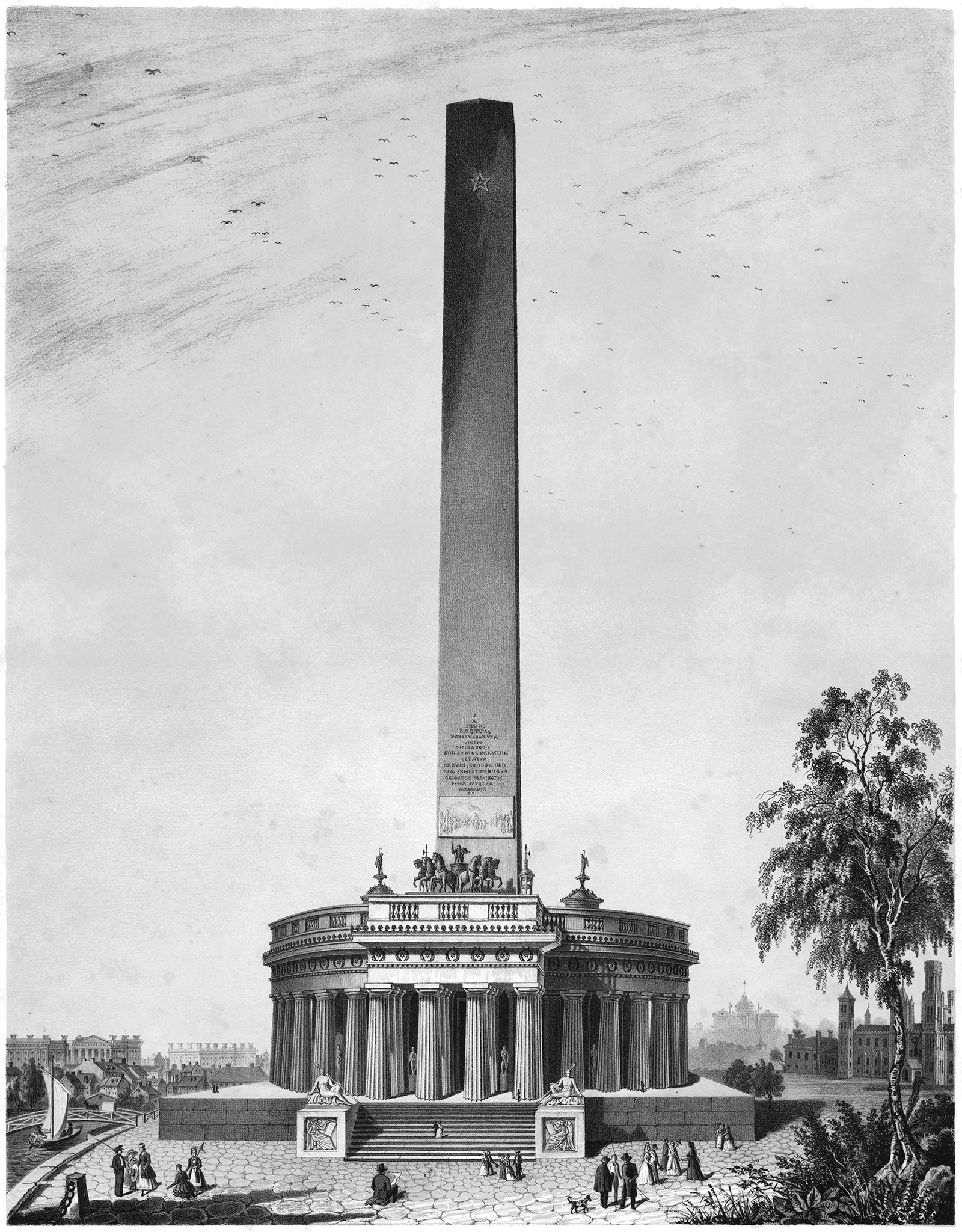

A Design for a National Memorial

Monuments and memorials are tricky beasts to design. Unlike a normal building, they’re imbued with meaning and symbolism that can be highly subjective. They’re not just buildings, but repositories for history and memory. This means they carry responsibilities to the person or event they are meant to symbolize. That’s what makes the above illustration so difficult to understand. It’s described only as Design for National Memorial. This is tough, because it doesn’t even make a claim to what it’s memorializing. One thing is clear, however; the designer was motivated by verticality.

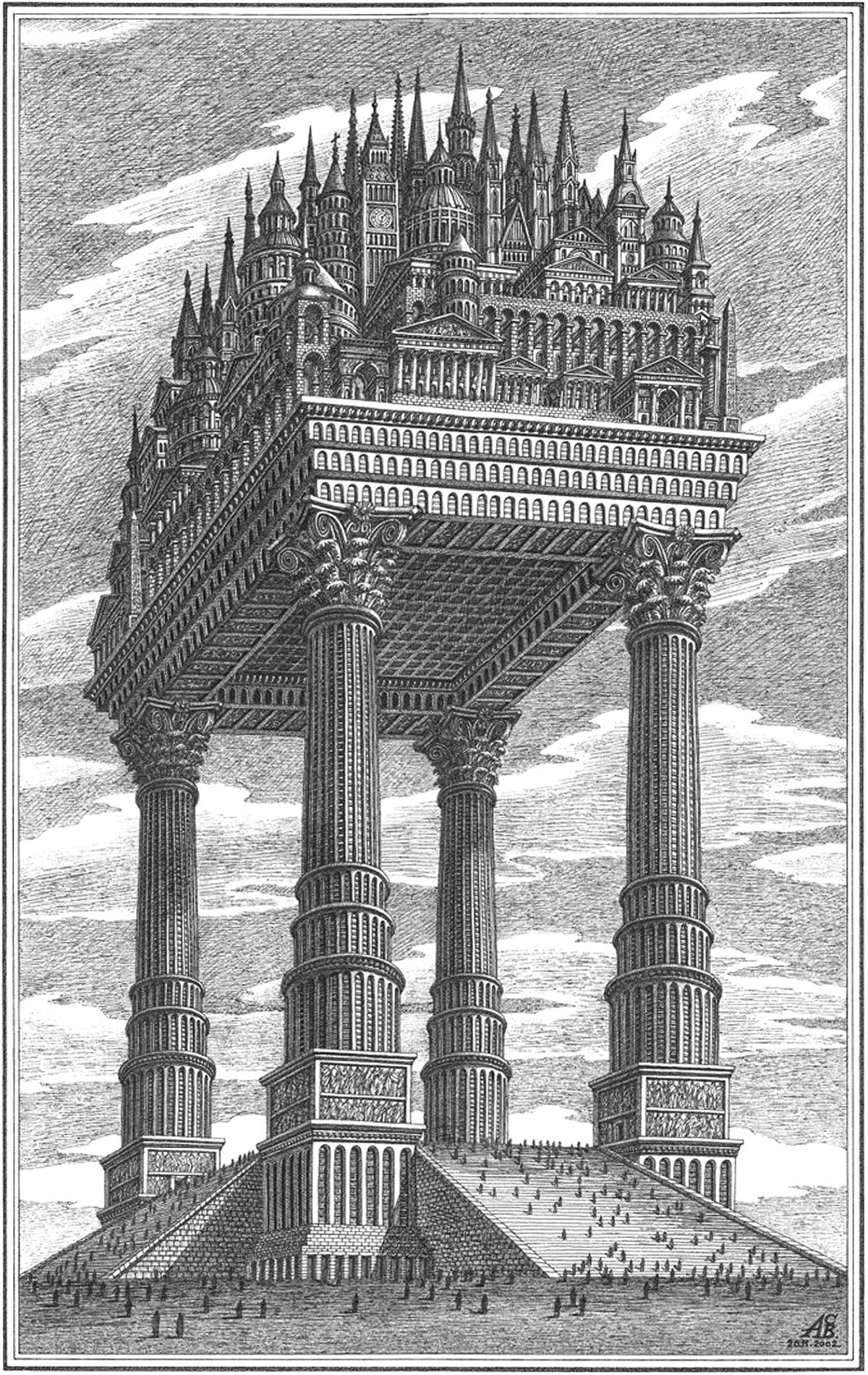

The Magic City

Pictured above is an illustration by Russian architectural theorist Arthur Skizhali-Weiss. It’s part of a series called The Magic City, which includes fictional realities dreamed up by the architect from 1999 to 2014. Apart from being an interesting composition of architectural forms, it embodies a few themes related to verticality.

Constant-Désiré Despradelle’s Beacon of Progress

He was possessed by the idea of a monument embodying the characteristics of American civilization, to be a memorial to the genius of the American people and a reminder of the glories of the Columbian Exposition in Jackson Park. These words describe the feeling of Constant-Désiré Despradelle after he visited the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893 in Chicago. The exposition saw an entire complex of temporary buildings built in Jackson Park, only to be demolished after the fair. For Despradelle, Chicago needed a permanent monument to embody the spirit and grandeur of the fair. He set to work designing his vision, and the final result is pictured above.

The New York American Journal Headquarters

Throughout my research into tall buildings and verticality, I’ve come across myriad examples of proposed and unbuilt structures. Some are alternate proposals by famous architects. Some are one-hit wonders that make their way into the mainstream history of skyscrapers. Some, like the one pictured above, are just intriguing and obscure images without much context. Details on this building are scarce, but from what I can find this is a proposal by Barney & Chapman Architects for the headquarters of the New York American Journal. It was located at Columbus Circle in New York City, on the site occupied by the Museum of Arts and Design today.

The Proctor Steel Tower

When the Eiffel Tower was completed for the 1889 World’s Fair in Paris, the world took notice. France had constructed the world’s tallest structure, and it immediately became the envy of the world. The next World’s Fair would take place in Chicago in 1893, and the organizers wanted to take the opportunity to out-do the Eiffel Tower with their own structure. The most successful proposal was the Proctor Tower, which is pictured above. It was 335 meters (1,100 feet) tall, which is roughly 12 meters (40 feet) taller than the Eiffel Tower.

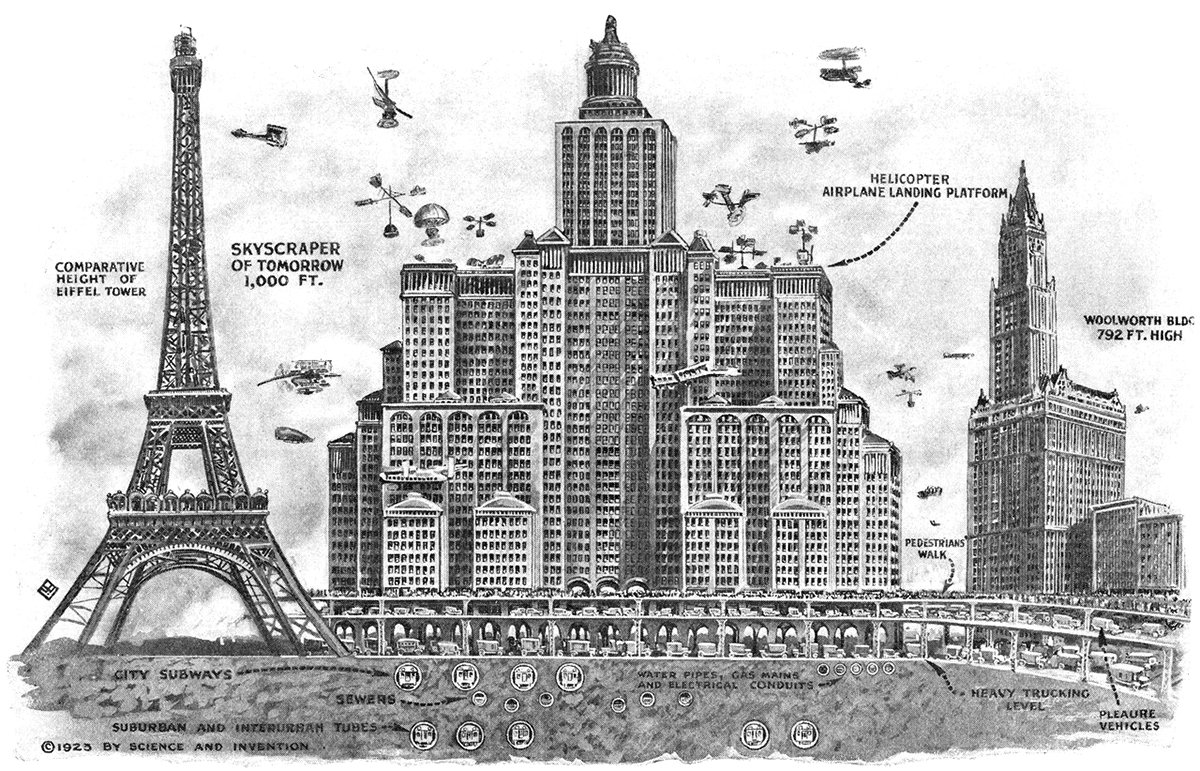

Skyscrapers of To-morrow

Pictured above is a 1923 illustration showing Harvey Wiley Corbett’s idea for a future skyscraper. Corbett believed buildings would continue to get taller and wider, resulting in massive, slab-like structures with aircraft landing platforms on their roofs and multiple underground levels of traffic. He compares his concept with two iconic buildings of the time, the Eiffel Tower and the Woolworth Building. These were both the tallest in the world when completed, which really hits home the sheer scale of Corbett’s structure.

Friedrich Gösling’s Proposal for the Reichstag

Pictured above is a competition entry for the original Reichstag building in Berlin. It was designed in 1871 by German architect Friedrich Gösling, and it’s a big departure from the Neoclassic design that ended up getting built. Gösling intended the design to embody the German way of life and the German idea of the state. He expressed these ideas with an organic plan and a Neogothic structure that seems to point upward with its myriad steeples and pinnacles. I suspect this upward focus was how Gösling’s idea of the German way of life in built form, because it’s so prevalent throughout his design. He was using verticality to project a sense of optimism about Germany and its future.

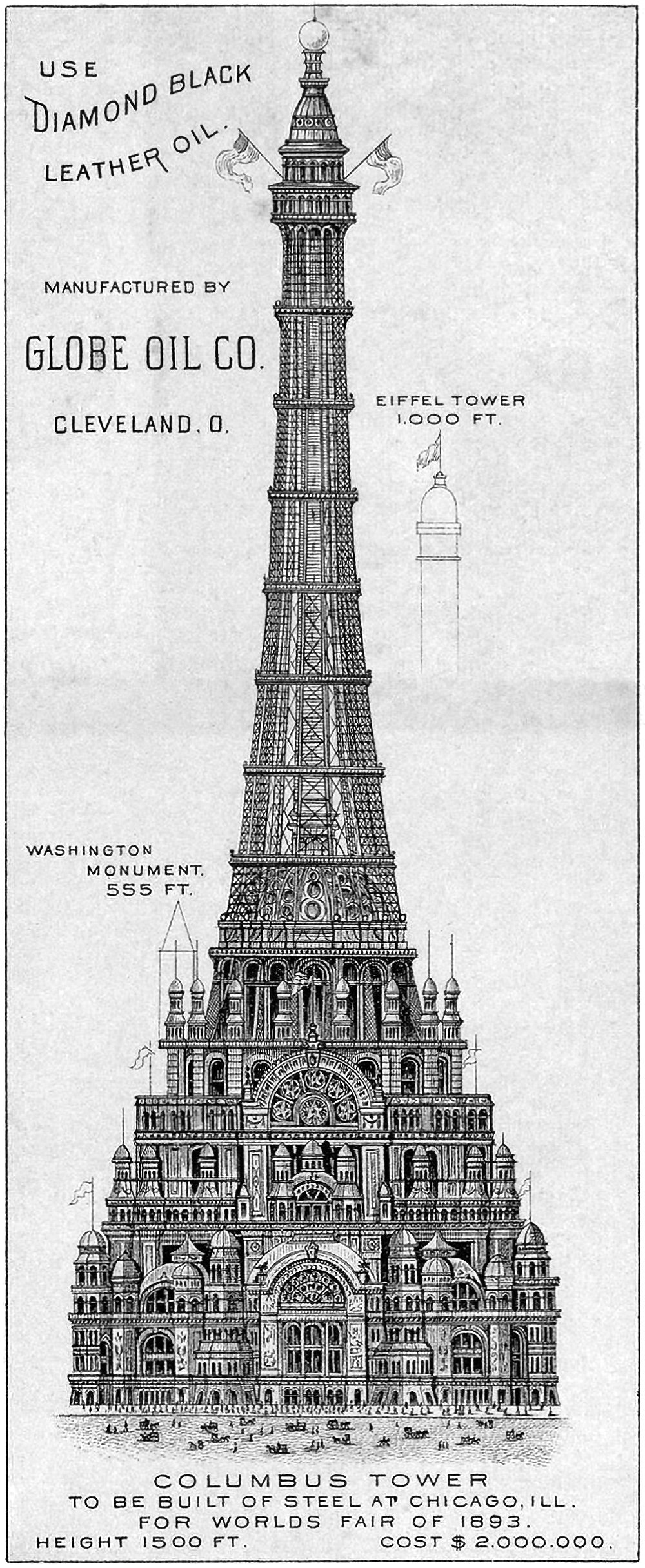

The Chicago Columbus Tower

Pictured above is the proposed Chicago Columbus Tower, which was designed to be the centerpiece of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. It was 455 meters (1,500 feet) tall and would’ve cost two million dollars at the time (roughly 62 million dollars today). It’s an elaborate and ambitious proposal that was meant to out-Eiffel the Eiffel Tower, which was built for the previous World’s Fair in 1889. As if to hit this point home, the above illustration includes height references to the Eiffel Tower and the Washington Monument, which would’ve been dwarfed by this new structure.

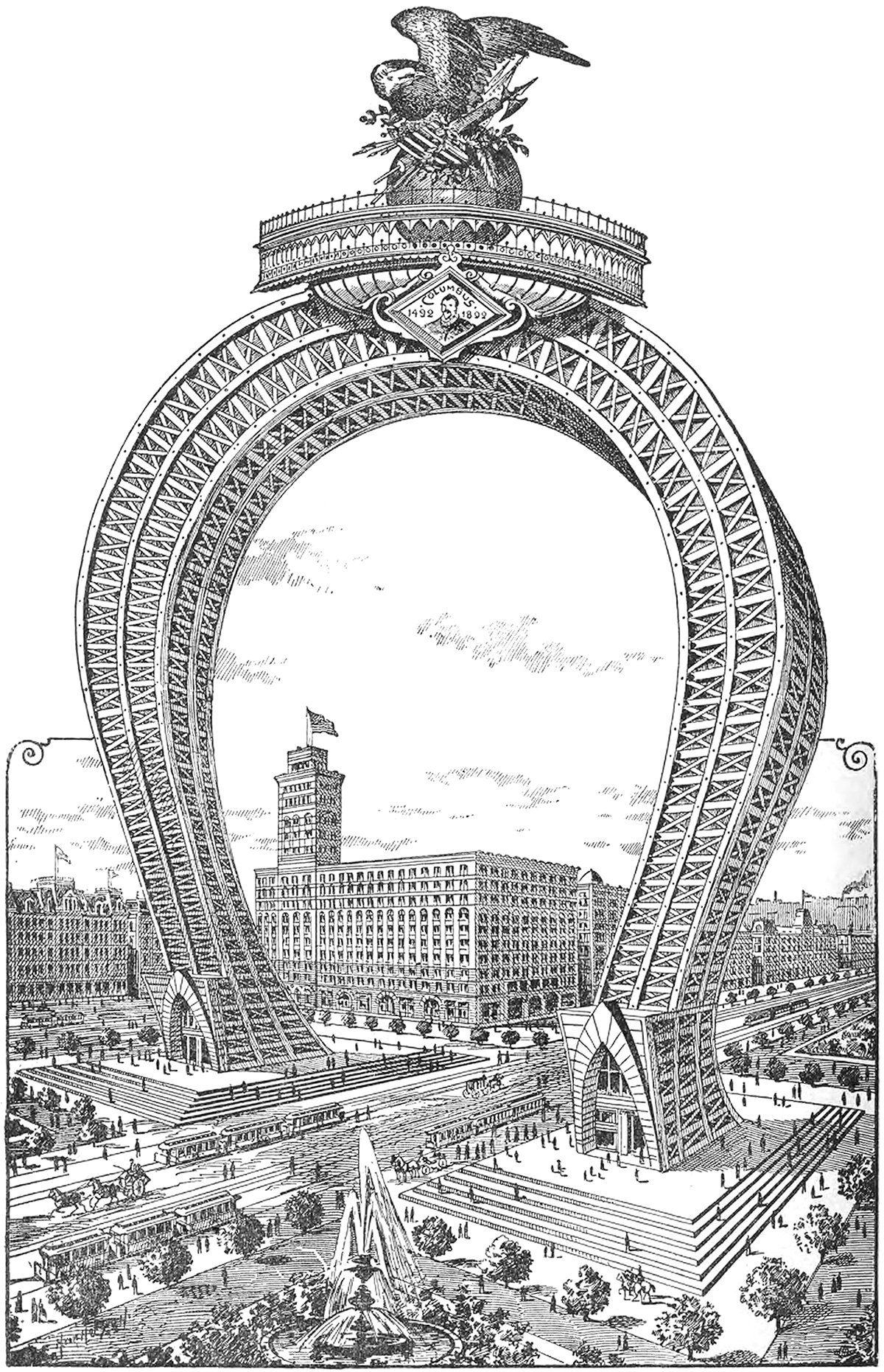

The Columbian Triumphal Arch

Here’s a doozy. It’s an 1891 proposal for a monumental arch that would’ve been the crown of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. It would’ve straddled South Michigan Avenue on the block adjacent to the Auditorium Building, which can be seen just behind the arch in the illustration. I can’t find any information on the designer, but whoever drew it up was no stranger to the Daniel Burnham quote make no small plans.

Best-Laid Plans : The Metropolitan Life North Building

The best-laid plans of mice and men oft go astray. This quote pretty much sums up the story of the Metropolitan Life North Building. What began as a design for the world’s tallest building ended with a bulky mid-rise building that feels too grand for its modest height. Pictured above is an illustration of the original design, located on the east side of Madison Square Park in New York City. Topping out at 100 stories tall, it would’ve been the tallest building in New York by a long shot. Then the Great Depression happened.

The Larkin Tower

Nearly all proposals for the tallest building in the world include some type of defining element or design flourish that make them unique and memorable. The Chrysler Building has its metallic crown. The Empire State Building has it’s mooring mast and antenna. Not the Larkin Building. It was designed in 1926 for a site on 42nd Street on Manhattan, and it was 368 meters (1,207 feet) tall, making it the tallest structure in the world by a long shot. Aside from this, there’s not much else to say about it.

The Towering Centerpiece of an International World Centre

Pictured above is a monumental tower designed by Ernest Hébrard as part of a design for an international world centre. It was a visionary project without a real location, and I suspect it was either academic, or he designed it in order to make a name for himself as an architect and an artist. Either way, this tower was the centerpiece of a much larger plan, but it speaks volumes about Hébrard’s intent with the plan.

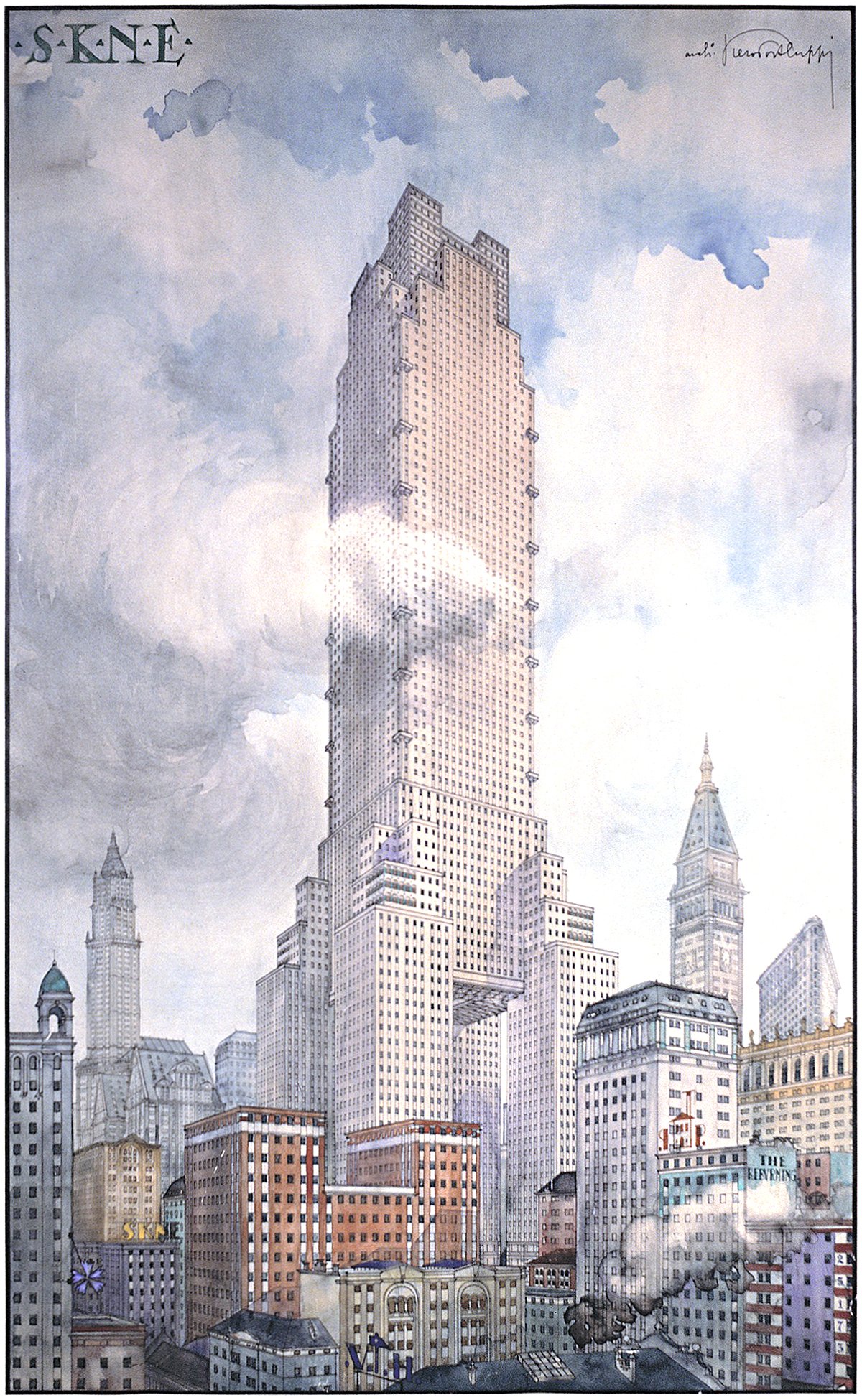

Piero Portaluppi’s SKNE Company Skyscraper

Pictured above is a conceptual design for a skyscraper by Piero Portaluppi from 1920. It was designed as the headquarters of the SKNE company for a site somewhere in New York. There’s two interesting angles here. The first is the tower itself, and the second is the method of representation shown.

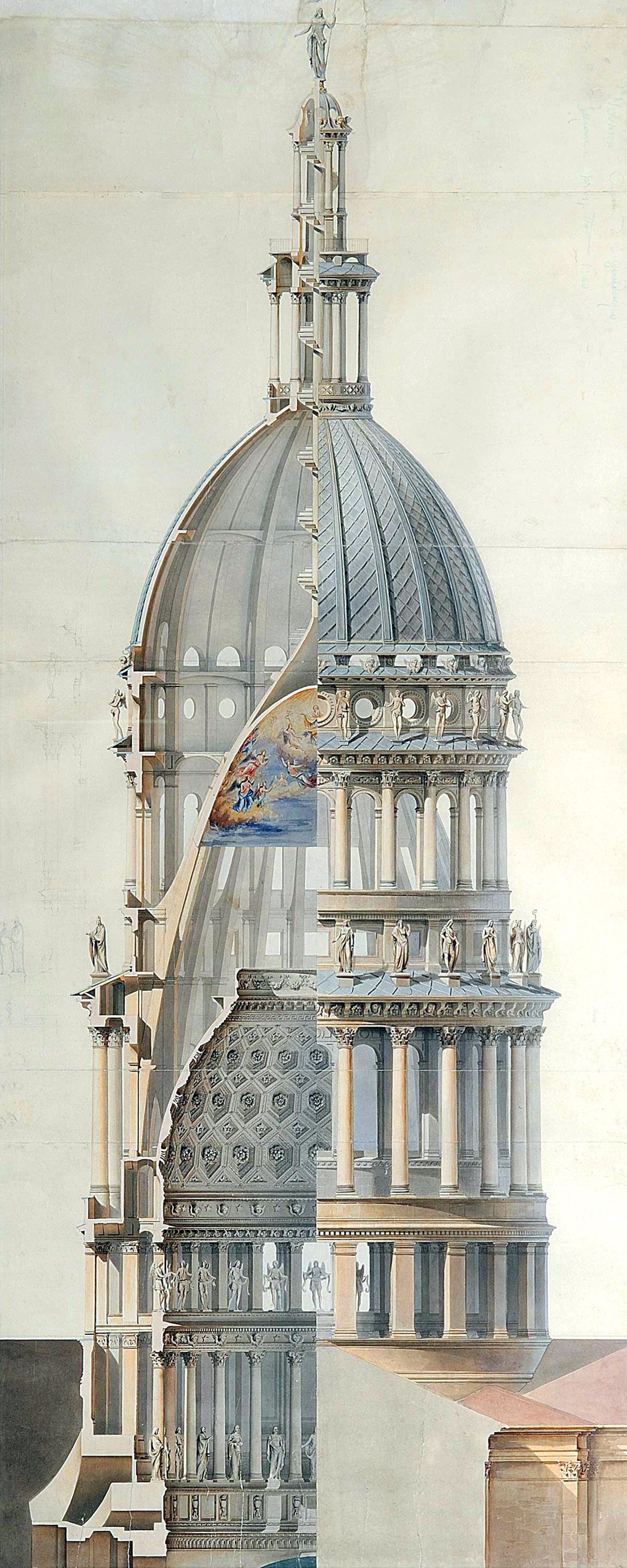

Alessandro Antonelli’s Basilica of San Gaudenzio

Pictured above is an elevation of the Basilica of San Gaudenzio in Novara, Italy. The building features an elaborate dome and cupola structure. This structure appears to be on steroids, with quite a few stacked-forms below and above the dome itself. It seems over-built compared to the building it caps, and it’s overtly vertical design is a statement from the architect regarding the power of verticality.